[ad_1]

On Dec. 9, 2001, 48-year-old Kathleen Peterson was found battered and bloodied at the bottom of a staircase in her Durham, North Carolina, mansion. Although her self-professed devoted husband, veteran and author Michael Peterson, seemed distraught on his frantic 911 call to police, he was arrested on first-degree murder charges days after his wife died of head injuries ― injuries some experts argued could not have been caused by a fall down the stairs.

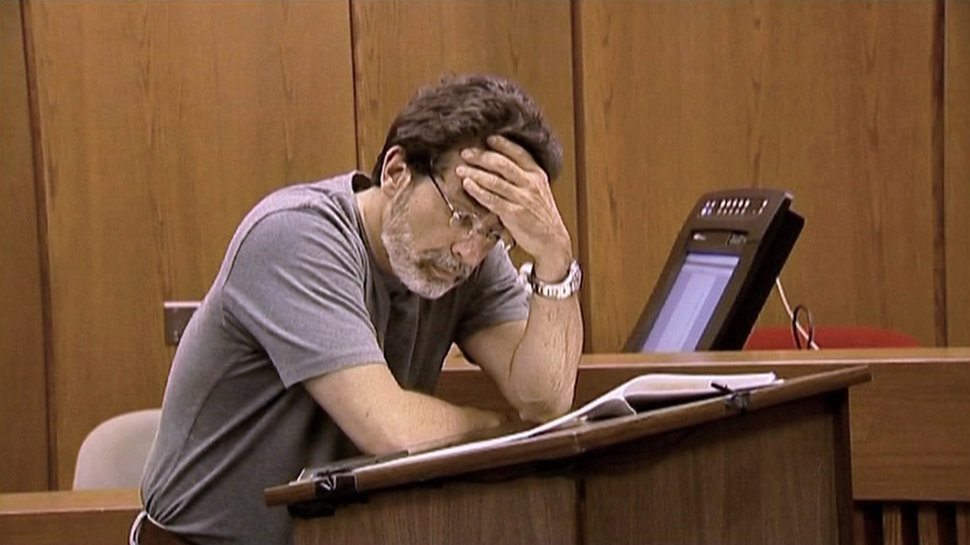

Enter David Rudolf, the man hired to refute those charges.

Rudolf is one of the many supporting characters in Jean-Xavier de Lestrade’s true-crime series “The Staircase,” which originally aired 10 episodes in 2004 and is now streaming in full on Netflix with three new episodes. To this day, Rudolf isn’t entirely on board with Peterson’s decision to invite a camera crew behind the scenes of one of the more controversial murder mysteries in recent history.

But he is willing to tell his side of it.

For him, the process of litigating ― and re-litigating ― Peterson’s legal saga was “emotionally unbearable, honestly.”

In an interview with HuffPost, Rudolf recounted his experience, starting from the beginning. Back in ’01, he was a criminal defense attorney recently famous for defending Carolina Panther Rae Carruth, accused of murdering his pregnant girlfriend. The very wealthy Peterson recruited Rudolf and an entire team of high-profile professionals (attorney Tom Maher, private investigator Ron Guerette and blood-splatter analyst and forensic scientist Henry Lee, who worked on the JonBenet Ramsey and O.J. Simpson trials) to vie for his innocence.

The team argued that the Petersons had an idyllic relationship, an idea supported by friends and family (specifically, Peterson’s adopted children, Martha and Margaret, and his kids from a previous marriage, Clayton and Todd). The team insisted Kathleen tumbled down her steps, tried to stand up and fell again, hitting her head multiple times. That’s how she died.

But the prosecution (led by Durham District Attorney Jim Hardin and his colleague Freda Black) alleged foul play at the hands of Peterson, citing the sheer amount of blood found on the staircase and walls, and the wounds to Kathleen’s head. At trial, Hardin and Black pointed to the eerily similar death of Martha and Margaret’s mother, brought up Peterson’s bisexuality, and suggested he used a blow poke to kill Kathleen. Despite the shaky argument, they were convincing enough to members of the jury. They found Peterson guilty of first-degree murder on Oct. 10, 2003, nearly two years after Kathleen’s death. Peterson was sentenced to life in prison at the age of 63, much to the shock of his legal team.

But that’s not where the story ends.

WhatsUp/Netflix

Eight years later, following multiple appeals, a bankrupt Peterson was released from prison on $300,000 bail. A judge found that State Bureau of Investigation blood analyst Duane Deaver ― a key prosecution witness at Peterson’s trial ― provided misleading information about bloodstain evidence, opening the door to the possibility of Peterson’s indefinite freedom.

A new trial was set for May 8, 2017.

But before that could happen, Rudolf negotiated an Alford plea on Peterson’s behalf, in which a defendant asserts innocence but admits there’s sufficient evidence to convict him of the offense ― voluntary manslaughter in this case. Peterson was sentenced to 86 months in jail, which he’d already served. Peterson was free, and Rudolf, representing his client pro bono at this point, felt liberated, too.

In our phone conversation, Rudolf spoke about how the tumultuous, years-long case affected his personal life, and exactly why Peterson allowed de Lestrade access to his work on the trial ― culminating in a documentary that critics have deemed less than objective.

And, yes, Rudolf addressed the much-discussed owl theory, which claims Kathleen Peterson was actually attacked by a bird.

Do you promise to tell the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth during this interview?

You’re going to put me under oath right at the beginning, huh?

Yes, I do. But I have to affirm rather than swear.

So you’ve, of course, recaptured the attention of the public after Netflix released new episodes of “The Staircase.” How have you handled it?

It’s been interesting for me. My goal from the start of this was to allow the public to see what really goes on from a criminal defense lawyer’s perspective in a case, how the system works or does not work. Of course, when you’re in the middle of the trial, that becomes very much secondary to what’s going on in the courtroom.

But now, 16 years later, as I’m seeing the comments and the reviews, people commenting on Twitter and that sort of thing, I realize that I think it achieved its purpose. Which is not so much whether a particular person is guilty or innocent. I leave that to people to decide on their own. But rather to the point being that there are some real problems in the criminal justice system that really do need to be addressed, and that criminal defense lawyers are not the problem. We are, hopefully, a part of the solution.

Is that something that initially drew you to the series? Because I’m curious how you felt when a French camera crew came to you guys and said, “We want to film this entire process.”

I felt uneasy. Uneasy and opposed. I was not the least bit an advocate for doing this ― it was really Michael. First of all, it was the quality of the people who approached us. The fact that Jean had won an Academy Award for “Murder on a Sunday Morning,” and we were all able to watch that and see how it was handled, that was a big piece of it, I think.

But it was really Michael who said, “You know, I’m not going to get a fair trial here, and I’d like to have a record, if you will, of what happens.” I was reluctant at best, and opposed for the most part. But at the end of the day, they were very respectful of my time. And I think that they captured a lot of what goes on behind the scenes. So I feel OK about how it came out.

The access you guys granted them was pretty incredible. How were they able to get that kind of access in the courtroom? I would think that the court would maybe be opposed to documenting those kinds of moments.

Part of the reason I agreed to this from the start is that I knew Judge Hudson was going to allow more TV ― pretty much unfettered access to the courtroom. I think he, over time, got comfortable with how Jean and his crew were going to conduct themselves. They were never disruptive in the courtroom, they were always very respectful of the process, and I think that the sheriff’s department felt the same way over time. So, it really wasn’t much of a dispute over any of that. No one really pushed back.

And is it true that Jean did initially have a crew that was with the prosecution team, as well?

Oh, absolutely. It was the same crew. Certainly they were filming with the prosecution’s blessing up to the time of the exhumation, because there’s those interviews with [Detective] Art Holland in his car, and in various other places. But sure, at the beginning, they allowed the French film crew into their meetings. Hardin gives a number of interviews. But then, at some point ― and I don’t know why this happened ― they just decided to cut off access. And so, there was very little of them toward the second half of the documentary.

We even saw Candace [Zamperini, Kathleen’s sister who sides with the prosecution] have a few moments in the documentary in the library and things like that. I guess she ended up backing away.

That was during the trial. Caitlin [Atwater, Kathleen’s daughter, who also sided with prosecution] had given some access early on. So yeah, I think it’s false to say that they had no access. But I think it is fair to say that as a result of decisions made by the prosecution that their access was limited.

WhatsUp/Netflix

Jean has said that some of what they filmed actually helped you later on, especially with the video footage of Duane Deaver and some of the blow poke discussions. Is that true?

Absolutely true. I went back and reread Deaver’s testimony in preparation for that hearing. And for me, it brought it all back, obviously. But there’s a real difference when you then go to the footage and you watch his demeanor and his facial expressions and how he’s playing to the jury. It just brings you right back to the courtroom at that moment in time. It was powerful for me. And I think it had to be powerful for Judge Hudson, sitting there, watching what had happened 10 years earlier. I never talked to him about it, but I think it had to have made it more real for him ― what a pathological liar Deaver had been during the trial.

Let’s discuss the initial guilty verdict for Peterson. When you’re watching the series, it just seems so surprising, I think, to the viewers. How shocking was that moment for you, after all the work you put in? I thought for sure there was reasonable doubt.

No one, and I mean this sincerely ― and I think this probably also includes the prosecution team ― no one expected a guilty verdict. There was a split of opinion about whether there would be an acquittal or a hung jury, but no one thought there would be a guilty verdict. So, when that verdict came out, as I say in the documentary afterward, it was devastating. It was like, “Was I in the same trial as those 12 people in the box?”

You go through trials and you have bad days and good days. Sometimes you come back to the office at the end of the day, and you say, “God, I’m glad that day was over. That killed. I hope we do better tomorrow.“ There was never a day like that [during Peterson’s trial], ever. No matter how damaging the direct evidence would be, by the time the cross-examination was finished, it had turned at worst neutral and often times favorable. So, when you’ve experienced that day after day, and then the jury who’s watching it all comes back guilty, it’s disorienting, really. It sort of made me wonder, were we watching alternative universes?

Do you think the bisexuality theme that the prosecution really kept homing in on, especially Freda Black in her closing statement, affected the verdict at all?

Yes, I do. I think the combination of the bisexuality and the Germany stuff [Martha and Margaret’s mother’s death] was just deadly, because it made the jury ignore all the other [evidence]. And, if you think about it, it was absurd. Suppose Michael had had affairs with women before his marriage, or had called an escort three months before this happened but never met with the person. Do you really think that a judge would allow that in? I don’t think so. It would be irrelevant. It was all about his character and what kind of person could engage in bisexual behavior. That’s really what the whole purpose of the evidence was, in my take.

When the verdict comes in and everything you’ve done for a year just gets flushed down the toilet, that’s really when the emotional impact of all this really gets you.

David Rudolf

For you, another tough decision was when Michael wanted you back on his side in the new episodes, and you kind of tell him, “Listen, I don’t know if I can do this again. This not only affected your life, it affected my personal life, as well.” I’m sure viewers want to know what your personal life was like being the defense attorney for Michael Peterson.

Well, it became all-consuming, in truth. When you’re in the middle of a trial, it’s sort of like if you’re in the middle of a sporting event, and I don’t mean to analogize it, but you’re in the moment. You’re running on adrenaline and you’re working 18-hour days, seven days a week. Things are coming up that you have to deal with in the moment, and so you really don’t have much of a chance to really get in touch with how this is affecting you on any kind of personal level. But then, when the verdict comes in and everything you’ve done for a year just gets flushed down the toilet, that’s really when the emotional impact of all this really gets you.

On a sort of personal level, I desperately wanted to make it right. Not that I blamed myself, because I didn’t. I just thought it was so wrong, I just wanted to make it right. We lost the appeal, and that was another emotional blow. Because the court of appeals agreed that the prosecution had made errors, and the judge had made errors, but they just sort of wrote them off as pompous. That was devastating. Then, the owl theory came out, and it became sort of a joke, and I think that was unfortunate. Then everyone, even people who had been supportive of Michael, over the next couple of years, sort of changed their minds. That was sort of depressing. By the time I found out that they finally proved that Deaver was a liar, period, and Michael was to get a new trial, it was a like a huge, huge emotional relief. I don’t know if you can tell it in the episode where the retrial is granted, but it’s just this wonderfully exhilarating, freeing feeling that I’ve done this, wherever this would go.

And then, I very much wanted to try to resolve the case, because I thought it just needed to be over. I just couldn’t imagine putting myself in the same emotional wringer. My life had changed. At the time I had an 8-month-old daughter and I was living in Charlotte. Going back to that scenario, back in Durham for months with the same cast of characters was emotionally unbearable, honestly.

WhatsUp/Netflix

You mentioned the owl theory. A lot of people who have followed this case are kind of obsessed with this theory. Can you talk about it a little bit more, and explain why it wasn’t featured in the documentary?

First of all, it really was not part of the trial at all. I guess this is my bad, but it just never occurred to me. Sure, I thought those wounds were bizarre-looking and there were some things that didn’t really fit, but the fact that some animal or bird could have done this just never crossed my consciousness. It really wasn’t until about a day or two before closing argument that [lawyer] Larry Pollard came to my office and raised it.

He had already run it by Jim Hardin, as though Jim Hardin was going to say, “Oh, my goodness, Larry, you’re right. Let’s just dismiss the case, and we apologize to Mr. Peterson.“ I mean, that wasn’t going to happen. Then, he came to me and I couldn’t do anything, because I was a day before closing argument. Then, Larry sort of rolled out the theory and I don’t think he really had his ducks in a row at that point in time, so it became a joke. It truly became a joke. No one honestly took it seriously.

[Later on], people went back to the file and found the references to the owl, to the feather in her hair, the blood, and all the sudden there was some publicity about people who had been attacked by owls and videos of, literally, owls attacking people’s heads from on YouTube. None of that existed back in 2001. In some ways, it’s sort of a reflection of social media. Who knew anything about YouTube in 2002 or 2003? I certainly didn’t. If you go to YouTube and type in “owl attacks on people,” you’ll probably come up with 50 videos.

As we prepared for the possibility of a new trial, we started looking into that. But I think from Jean’s perspective, at the end of the day, the documentary wasn’t about what happened in terms of Kathleen’s death, it was what happened to the criminal justice system.

Yes, Jean has said he wanted to show viewers what was going on with the justice system, which a lot of these true-crime documentaries have been doing ― “Making of a Murderer,” etc. Do you think these films are doing a good job at shedding light on what you, in your profession, see in the courtroom day to day?

Yes, and not just in the courtroom but outside the courtroom. I have represented people who were subjected to what Brendan Dassey [from “Making a Murderer”] was subjected to. It’s only recently that those things have been tape recorded. Fifteen years ago, Dassey’s interrogation would have never been recorded. There’d be a three-page report that would have been completely self-serving and exculpatory for the police.

So, yeah, I think it’s sort of like what happens with cellphone videos of police encounters with black men. We all knew that was going on. We represented those people. But nobody else knew, and now, what can you say? It’s there on the screen.

I read you taught attorney Jerry Buting, featured in “Making a Murderer,” who represented Steven Avery.

Yeah, I did. I did. I started a clinical program back at the University of North Carolina in ’78, and Jerry was in, I can’t remember, like the second or third clinic that I ran. And enough of the people who went through that clinic ended up being defense lawyers, which is a nice thing to see for me.

Have you caught up with him at all?

Yes, a little bit. Not at any length, but it hasn’t escaped our notices.

Have you checked up on Peterson since the Alford plea?

I think he is doing as well as any human being can do having gone through what he did. He’s doing his best to enjoy his life, to be close to his family, to his grandchildren, and I think he’s finally had a chance to really grieve.

And how are you doing since all of this? Has it kind of been a relief for you that it’s over?

Yes. After that trial, I sort of changed the focus of my practice. I still do criminal cases from time to time, but I’m doing a lot of wrongful-conviction litigation, representing people who were exonerated after being in prison for years and years and suing the police officers, like Deaver, who were responsible for those miscarriages of justice. That’s been a very rewarding coda to my career.

“The Staircase” is now streaming on Netflix.

[ad_2]

Source link