[ad_1]

It always feels compulsory: I’m hungover or sad, eating takeout with friends. Then it’s like I’ve been hexed, the spirit of a queer ancestor overtakes my body as I grab the remote. The next thing I know, my battle cry bellows.

TALKINGLAUGHINGLOVINGBREATHINGFIGHTINGF*CKINGCRYINGDRINKING

I’m watching “The L Word” and it’s a day that ends in -y.

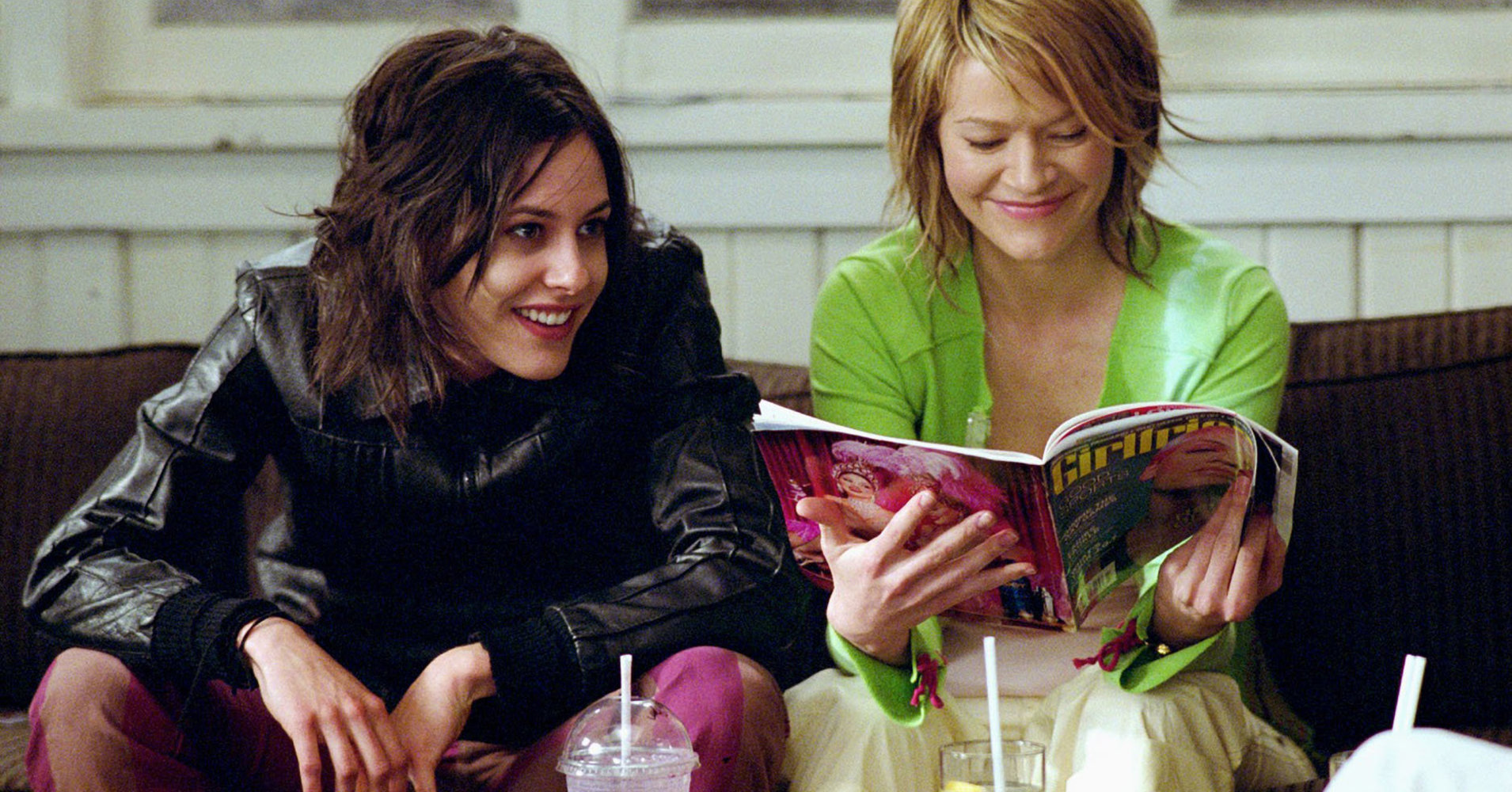

The Showtime behemoth premiered on Jan. 18, 2004 to immense buzz. Created by Ilene Chaiken, Michele Abbot and Kathy Greenberg, the drama about a group of queer women living, loving and lusting in Los Angeles muscled through six seasons (the last of which we shall, uh, forget; I dub Season 6 the Godfather III of the show).

If you’re under the LGBTQ umbrella, it’s impossible to view this show without some personal introspection. “The L Word” came and went before the legalization of same-sex marriage and the repeal of Don’t Ask Don’t Tell. Fifteen years after it premiered, with a reboot reportedly on the horizon, dozens of people from the LGBTQ community agreed to dissect its herstory with me in honor of the years past. They shared their feelings about the show, both good (Shane! The chart! Jane Lynch! Alan Cumming!) and bad (lack of robust representation, substandard storylines for trans characters). In interviews and tweets and email exchanges, some people told me that they turned to the show joyfully, some ironically, and others disappointingly or out of obligation.

“I watched the pilot… the year I came out, or at least the year I started coming out, and I remember thinking, OK, you’re maybe a lesbian so I guess you maybe have to watch the lesbian show,’” Madison Malone Kircher, associate editor at New York Magazine, told me.

Yet somewhere between CRYINGDRINKING and TALKINGLAUGHING, everyone I spoke to landed on a similar conclusion: this show exists as a time capsule for so many young queer identities. There was nothing like it on TV.

“I watched Season 1 as it aired with one of my best friends, author Eva Hagberg (watching the show was instrumental in her realizing her own sexuality, just to give you a sense of the power art has on self-discovery!),” Somer Bingham, a musician and cast member of “The Real L Word,” wrote to me in an email.

“It 100000000 percent did. I was like, Oh fuck. Yep. Uh, I uh, huh, want to uh, go with Somer to the, uh lesbian parties,’” confirmed Eva Hagberg Fisher, author of the upcoming memoir How To Be Loved: A Memoir Of Lifesaving Friendship.

I did not consume the show before my slow, drawn out process of coming out as queer, which occurred well into adulthood. My earliest memory of “The L Word” may not be one at all: I think I stared at a promo poster in a New Jersey mall once. I might have been with my mom. I vaguely recall studying the cast members’ floating heads, eyes shut, lips parted. Some were kissing, maybe. They seemed bewitched by something. What was it? It felt familiar and foreign. I don’t know if I would have known myself sooner if I streamed the show on some now-defunct site or stumbled upon clips in a friend’s basement at a sleepover.

Regardless, “The L Word” left its mark on me as it did so many others who wound their way to the series after it first aired.

“I’d heard about [‘The L Word’] and knew I’d be interested in watching, but didn’t seek it out until my very first girlfriend and I came across the first season on DVD at the local Blockbuster,” wrote writer and editor Trish Bendix.

Some people I spoke to watched it with their partners or friends, while others watched it alone, in secret. For me it was Netflix, not Blockbuster, that let me access the show from the confines of my Park Slope apartment several years ago.

“I’d just come out as queer to my friends ― bi at the time ― but not to my family yet, so I watched it in my room in secret when my mom was at work,” Oliver Whitney, a freelance reporter, told me. “After I watched an episode, I made sure to clear the viewing history on our Showtime account by hitting play on a bunch of other random shows. I was sneaky.”

”I had to find other ways to watch like BitTorrent or binging it at my parents house over the holidays,” said Carolyn Bergier, host of podcast Dyking Out. “I paid for them to get Showtime so I could watch, and my mom even got into it. After college, I would go to my mom’s house and we’d watch it together which is as awkward as it sounds.”

The contrast ― between how ubiquitous the leading ladies were at the time, and how clandestine some fans’ relationships with the show remained ― still strikes a chord. The actresses graced the cover of New York Magazine. They won a GLAAD Media Award for Outstanding Drama Series in 2006. Golden Globe-nominated Jennifer Beals charmed her way through talk shows, representing her art-world-lesbian powerhouse character Bette Porter. A month after its premiere, Wayne Brady gleefully told her on his talk show, “The show has hit its stride so fast… it’s become so popular!” Even The New York Times’ review, while rightfully objective, still recognized its groundbreaking appeal:

This is a breakthrough in the annals of television’s fantasy life. Being an L myself, a member of a group that has had a spotty presence on the small screen, I can testify with authority to the despair of bouncing along a life of risk, mystery and heartbreak only to turn on the TV and see two women in bad pantsuits gingerly touching one another on the forearm. ″The L Word″ tosses those pantsuits to the wind, and good riddance to them.

“I read about the show before I wrote about the show, so my experience as a reader was that the show was positioned as sexual and tantalizing, both in how it was marketed and how it was received,” said Bendix, who later wrote for “The L Word’s” website spin-off OurChart (which was based off bisexual character Alice Pieszecki’s intricate web of past relationships and hookups). “There were so many hyper sexualized photos of the actresses that I found highly frustrating, because yes, the show had a lot of sex, but it wasn’t JUST girl-on-girl for the straights to see.”

According to Merryn Johns, editor-in-chief of Curve Magazine and former editor-in-chief of Australia’s lesbian magazine LOTL, the show was promoted as a glamorous Los Angeles soap in Australia ― not explicitly as a queer vehicle. “When the advertisers found out what it was really about they pulled their advertising and there was a quite a fuss,” she explained over email. “Once everyone got over the initial shock, however, the coverage was very positive and many straight people watched the show, too.”

Regardless of how it was marketed, the series chose to introduce audiences to “The L Word” universe through the character Jenny Schecter, a “sexually fluid” writer who moves to the city with her then-boyfriend. After realizing her neighbors are ~power couple~ Bette Porter and Tina Kennard, Jenny messily embarks on a quest to understand her queer identity. Today, you can mention her name to any viewer and they’ll likely roll their eyes.

“I believe that the show’s limitations speak to the time more than they do about the creators,” Johns said. “For example, the fact that they needed to use Jenny as a device ― this questioning character who stumbles upon a hidden lesbian world ― rather than just dropping us into a gay milieu says a lot about how segregated LGBT culture was from mainstream culture at the time.”

Jenny cheats. She lies. She dates. She cries. She writes a memoir cheekily named “Lez Girls.” She directs its film adaptation, before getting fired from her own project. (“That whole season [where she was directing the film] should be stricken from the record,” wrote television writer and performer Lauren Ashley Smith, “She was the worst character.”) Oh, and Jenny gets killed off. The unsolved whodunnit birthed the “who killed Jenny?” meme that still reverberates as a queer inside joke.

“Jenny sucks,” wrote Priya Arora, staff editor at The New York Times, in an email to me, “Bette and Tina will forever be #goals.”

Cathy Renna, media activist and public relations guru, also agrees that Bette’s dynamism was undeniable, “I was always team Bette even with her flaws.” Bendix also chose Bette as her “problematic fave”: “She was a cheater, she was selfish, she was probably a Sagittarius (no shade ― I am one, too!), but she also wanted to do the right thing, and she made being a fierce feminist lesbian look really fucking cool.”

My affinity for Bette is unmatched, too. If I’m not some big-shot director stomping around in patent leather heels at a contemporary art institution, then have I even made it? But I also can’t talk about the cast without mentioning infamous heartthrob Shane McCutcheon. “SHANE FOREVER,” wrote Hagberg Fisher. “I loved Shane… After I did come out, my first girlfriend had a lot of physical similarities to Shane.”

″[Shane] was the perfect butch heartthrob, my type, and I loved how over-the-top of a player they made her,” admitted Beth Greenfield, senior editor at Yahoo, who told me she watched the show with her girlfriend-now-wife every week when it aired on Showtime. Jess Henderson, comedian and writer agreed, “I liiiiiiiiive for Shane,” who recently watched the series for a good laugh, “I love a fuck boi.”

Jenny sucks.

Priya Arora, staff editor at The New York Times

Jenny disdain aside, the show was fascinating in its ability to turn so many people off its deliberately crafted characters and still capture a sentiment that made queer viewers return episode after episode.

“Seeing so much queer sex, or ‘sex’ as it were, on screen was important for me as somebody who spent a lot of her younger years very much in the dark about non-heterosexual relationships,” Malone Kircher said.

“At its core, the show allowed me to see my future in a way I’d never seen it before,” said Megan Lasher, who first watched the show on her then-boyfriend’s Netflix account. “It’s the first time most of us saw happy lesbians, living their lives, and probably the first time any of us were given permission to lust over a woman, who was there for us, not for the male gaze.”

(Now a senior manager of content strategy at Hearst Digital Media, Lasher also told me after she binge-watched the show years ago, she eventually left her boyfriend, changed her Tinder preferences and “never looked back.”)

“The L Word” broke the TV mold, but it had its flaws. The characters, mostly white, femme and middle class (or wealthier), represented a small part of the LGBTQ+ community.

“The lesbian community does not look like this mostly-white, mostly-cis cast,” Lasher wrote in an email.

“I neeeeeeeeed to see something other than a bunch of SKINNY and WHITE queers,” observed Henderson.

“Butch women are practically nonexistent on the show, yet they make up such a large part of the lesbian community,” stated Bergier.

The show particularly failed the trans and nonbinary communities with its portrayal of trans character Max Sweeney. Played by gender fluid actor Daniela Sea, the character, while the first recurring trans character in a scripted series, felt one-dimensional, a vessel to perpetuate toxic stereotypes. His storylines –– such as Max’s eventual pregnancy –– could be confused for cheap tabloid fodder.

“It’s so weird to watch a show be so proud of itself for featuring a trans character while simultaneously treating him so poorly,” Sarah Kennedy, comedian and contributor at Reductress, explained.

Whitney rewatched Max’s episodes after coming out as trans and realized how much “The L Word” contributed to so many “negative perceptions of what it meant to be trans masculine.” More upsettingly, Whitney said the medical details of Max’s transition were unsound or dismissed.

“His episodes are full of inaccuracies about medically transitioning ― HRT suddenly turns him into a hyper-aggressive asshole, he grows a beard in like two episodes, etc.,” wrote Whitney. Lasher noted that “Max’s transition should have been written by real trans and GNC people.”

“At points I was unsure whether the other characters’ transphobic jibes were meant to be a critique of society’s transphobia, or complicit in it,” wrote Yas Necati for The Independent in 2017. Brin Bixby, trans activist and founder of Bigender.net, agreed. “The thing about using a depiction of mistreatment and oppression as a form of commentary is that you have to present an alternative point of view AND depict it as superior,” Bixby explained via Twitter. “Or else you’re just propagating that mistreatment as normal ― you’re continuing the existing cultural narrative, not challenging it.”

Fifteen years after the pilot aired, the cultural narrative around so many issues “The L Word” tackled has shifted. In July 2017, Entertainment Weekly and Buzzfeed News confirmed that Showtime was working on a revival, which excited and incited various corners of the show’s fandom.

Shane actress Kate Moennig tweeted, “Cat’s outta the bag!” before several other original cast members joyously confirmed the news. With writer-director Marja-Lewis Ryan slated as this iteration’s showrunner and executive producer, there’s limitless opportunity to get things right, using the “Will & Grace” and “Queer Eye” reboots as prime examples.

“I could really go for some queer escapism,” Verizon Media senior engineer Andrew Theroux wrote, “Bring on the high society, art-gallery owning, pantsuit wearing power lesbians! If “Charmed” and “Will & Grace” can get rebooted, so can ‘The L Word.’”

Most folks I spoke to want that reboot to happen with some changes. “If a new ‘L Word’ exists today it should be a show with more diverse queer characters –

racial diversity, economic diversity and inclusive of trans, GNC and

intersex folks,” Whitney wrote. “It should also be written and directed by a broad range of queer and POC folks.”

“I think they definitely should [do the reboot], but set in New York with a new cast of characters and for God’s sake a new theme song,” wrote Bergier, “Either that or just make a spinoff of Dana and Jenny as zombie roommates.”

[ad_2]

Source link