[ad_1]

On Tuesday, news broke that Laura Fleiss, the 31-year-old wife of “The Bachelor” franchise creator Mike Fleiss, had filed an emergency domestic violence restraining order against the TV mogul.

In documents obtained by the celebrity news site The Blast, Laura alleged that her husband had verbally and physically attacked her. He reportedly called her a “whore,” “low rent gold-digger” and “fucking cunt,” and demanded that she get an abortion. (According to Laura, she is currently 10 weeks pregnant with the couple’s second child, which Mike did not want.) As of Wednesday afternoon, Laura Fleiss had been granted a temporary restraining order, Hawaii police had opened a criminal investigation into the matter, and The Blast reported that Mike Fleiss claimed in court documents that his wife was the one who had attacked him.

In addition to Laura Fleiss’s allegations, The Blast published photos from the couple’s home security cameras that appear to show Mike pushing or striking her in the head, and photos of bruises and scratches she alleges resulted from this altercation. Warner Bros., the company that produces “The Bachelor” franchise with Fleiss’ NZK Productions, told news outlets that it is “aware of these serious allegations” and is “looking into them.”

It’s far too early to draw any conclusions about Fleiss’ guilt, however damning the evidence may seem. But regardless of how this case plays out, the allegations raise larger questions: What does it mean when the power broker behind a cultural product faces abuse allegations? What legal mechanisms exist to assert pressure and consequences on figureheads like Fleiss? And, perhaps more importantly, how should the knowledge of these allegations impact the viewing experience of “The Bachelor” franchise’s vast and predominantly female audience?

Among the primary aftershocks of the Me Too reckoning, which exposed the abuses of powerful men like Harvey Weinstein, was the recognition that huge swathes of our cultural landscape have been shaped by the stories these men tell. With a show like “The Bachelor,” though, it’s not just an artifact of the ’90s, like a Woody Allen movie or a Brand New song, that we must look at through a different lens. It’s a living thing, a massive cultural institution that has existed in very much the same form for almost two decades.

For the past two years, “The Bachelor,” which airs on ABC, has been going through its own version of a Me Too reckoning. There was the 2017 scandal on “Bachelor in Paradise,” when production of the show was temporarily halted because of an allegation of sexual misconduct. Warner Bros. investigated the incident and eventually concluded that there was no evidence of misconduct.

Additionally, there have been multiple revelations that male contestants on “The Bachelorette” and another Fleiss dating show called “The Proposal” have allegedly committed abusive acts prior to appearing on the show: A contestant on Becca Kufrin’s “Bachelorette” season had been charged with assault, and a contestant on “The Proposal” was alleged to have both facilitated a rape and perpetrated sexual assaults. Both cases raised urgent questions about how rigorously the production teams were vetting contestants before presenting them as ideal romantic partners.

Fleiss himself was driven to comment:

Warner Bros. and ABC have, however imperfectly and belatedly, addressed this problem by implementing new production guidelines and releasing “Bachelorette” cast photos months in advance so that viewers can come forward with information and allegations. Cast members are also the most visible symbols of the franchise, so it is unsurprising that the pressure exerted on production and the network to address allegations of harassment and abuse by viewers has been almost solely focused on casting.

An abusive male contestant is nothing but a liability for a franchise like “The Bachelor,” but provided his misdeeds are uncovered early enough, he can be easily swapped out for a less-risky option. Contestants hold no leverage in the world of the show — unless they become leads or winners — and in recent years, contestants have easily been yanked for less serious or substantiated accusations than those facing Fleiss.

Fleiss, however, is not so easily replaced. He is the creator of the show, the man behind its ideology, production and execution. The franchise is his intellectual baby, and the people who make the show — the producers and editors who are on the ground, doing the real work — are predominantly employed by NZK, his production company.

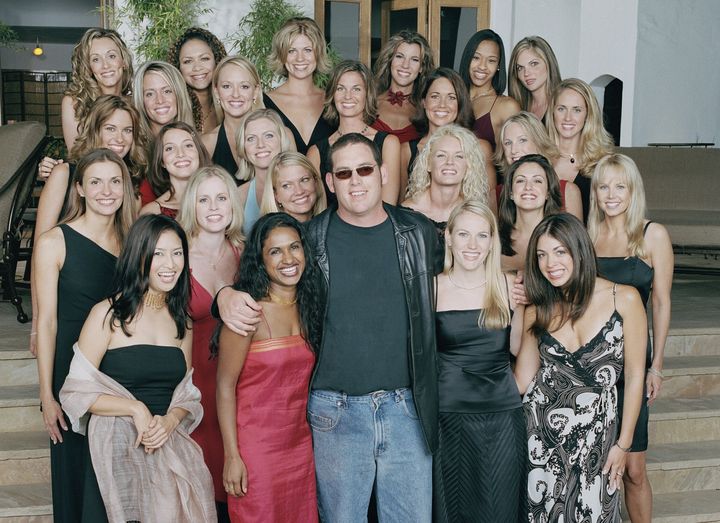

Fleiss’ first real reality TV success was Fox’s “Who Wants To Marry A Multi-Millionaire?” a one-night, two-hour televised special during which Rick Rockwell (who, it later came to light, had faced serious allegations of domestic abuse from his ex-wife) whittled down a group of 50 women to one and married her that night. More than 22 million people tuned in. That success is what got Fleiss’ proverbial wheels turning, and what ultimately led to “The Bachelor,” which premiered in 2002.

The new show carried over the successful ingredients of “Who Wants to Marry a Multi-Millionaire” — voyeuristic romance, simplicity of structure, the telegraphing of traditional family values through a decidedly untraditional, somewhat eyebrow-raising format — and changed what didn’t work. “The Bachelor” toned down the pageantry, upped the focus on lifelong commitment, and stretched out the series to six weekly one-hour episodes.

There is something seductive about looking that misogyny in the eye and picking each bit of it apart — on your Twitter feed or on a podcast. But at what point does using a flawed cultural product as a tool to analyze that flawed culture cease to justify its existence?

In a 2009 interview with Forbes, Fleiss said an envelope-pushing element is essential to his successful television endeavors. “I think you need a little bit of controversy to make any show go,” he said. “Look at Paris Hilton and Kim Kardashian — where would those girls be without their sex tapes? The shows that I’ve had that have been successful have always had a solid dose of controversy.”

To be painfully frank, Fleiss was right. His success with “The Bachelor” was not entirely a fortuitous accident: He recognized that selling audiences an image of romance and marriage that both seduced and shocked them would make for gripping television. The show didn’t just juxtapose a white-picket-fence vision of marriage with sexy “fantasy suite” dates and coarse competition for a mate — it capitalized on Fleiss’ own often-sexist impulses by playing up “cat fights” and gender roles. Even those who disapproved in one way or another often tuned in. By embracing the worst of heteronormative American courting, Fleiss gave feminists something to dissect and indulged the fantasies of more traditional audiences.

This, along with Twitter and a dwindling number of shows that count as “appointment TV,” has allowed “The Bachelor” franchise to flourish even during the years of Peak TV. Entire ecosystems of commentary and commerce have built up around it, including our own HuffPost recap show “Here to Make Friends.”

Although it has been reported that Fleiss is not involved with the day-to-day production of the show, it feels almost impossible to completely excise his influence from the franchise. What’s more, it’s hard to argue with the idea that “The Bachelor” can only exist because of the patriarchal, misogynist culture that it was born out of. There is something seductive about looking that misogyny in the eye and picking each bit of it apart — on your Twitter feed or on a podcast. But at what point does using a flawed cultural product as a tool to analyze that flawed culture cease to justify its existence?

To question whether “The Bachelor” offers a narrative fundamentally shaped by an abusive or misogynistic mindset would be to question whether a massive, ongoing institution should fall. Regardless of Fleiss’ guilt, or even of his current involvement in the show, that’s a question worth asking.

REAL LIFE. REAL NEWS. REAL VOICES.

Help us tell more of the stories that matter from voices that too often remain unheard.

[ad_2]

Source link