[ad_1]

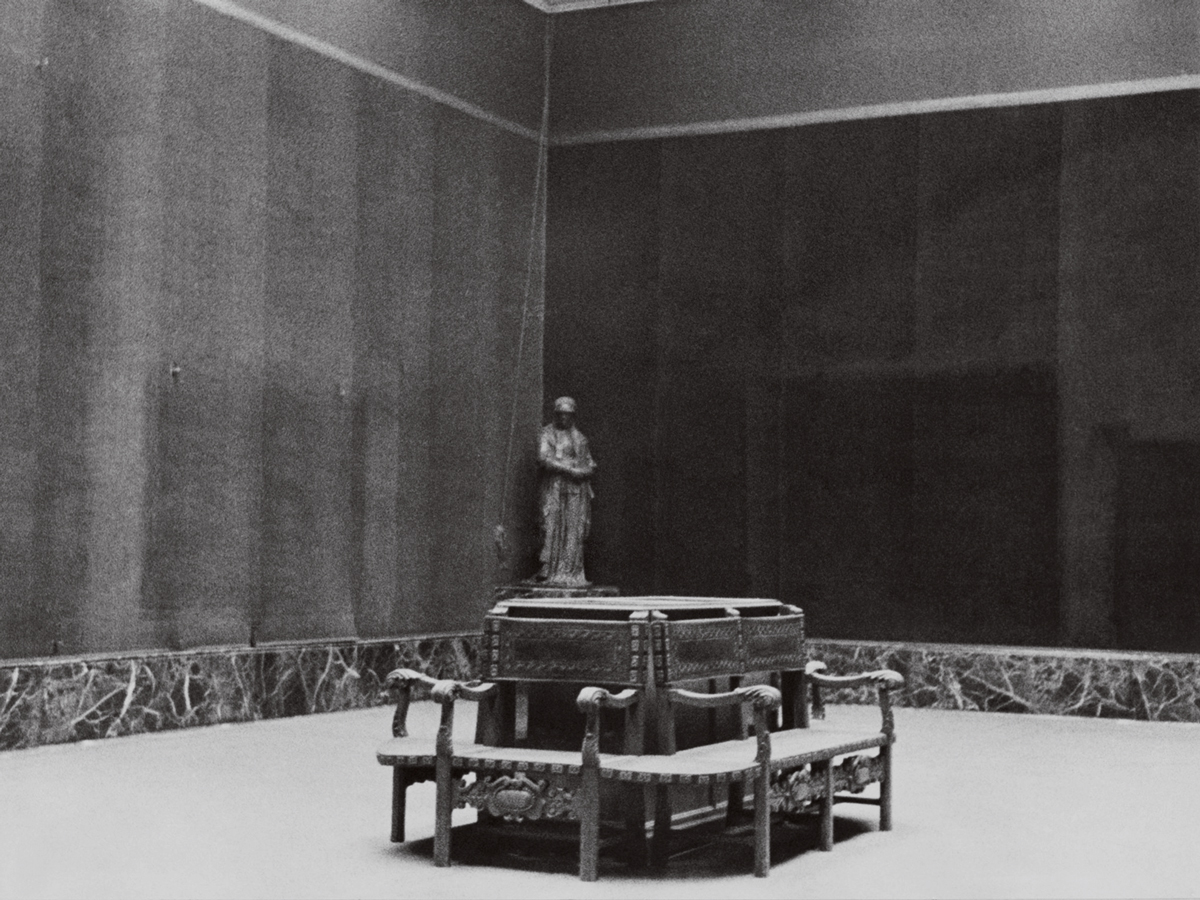

Interior view of Museo del Prado after important works from its collection were evacuated during the Spanish Civil War.

MUSEO PRADO

In March, Madrid’s Casa del Campo—a sprawling park near the city’s center—was urgently evacuated when an undetonated (and potentially active) bomb from the Spanish Civil War was found by a jogger. Only a few days earlier, a similar bomb had turned up on the campus of a university nearby. In fact, such instances occur with alarming regularity—at a rate of some 1,000 per year, even 80 years after the war’s close. The phenomenon offers a graphic example of how, in Spain as elsewhere, the past is rarely truly past—it can turn up at any moment.

Another bomb, this one no longer volatile, appeared in an even less likely location in Madrid: in the exhibition “Museo del Prado 1819–2019. A Place of Memory,” at the Prado Museum. The show, on view through this spring, was the centerpiece of a 200th-anniversary celebration of the Prado, with events focusing on the institution and its history. The bomb was part of a section dealing with the museum during the civil war, from 1936 to 1939, when firebombing by Fascist air squadrons led to the removal and temporary relocation of the Prado’s collection to Switzerland. (During that tumultuous time, Pablo Picasso was named director of the museum.)

The show traced the museum’s role in shaping and, at times, decisively sustaining, Spain’s changing sense of itself. The Prado was founded in the wake of the Napoleonic wars, at first housing the formidable Spanish royal collections that had been accumulated over the preceding centuries. The original collection would later be enlarged, primarily through works from disestablished religious orders in the 19th century and, to a lesser degree, through private bequests and donations. Meanwhile, the Prado became a pilgrimage destination for painters from Europe—France, in particular. Manet, for instance, revered works there by Velázquez and Goya.

For “A Place of Memory,” Javier Portús, the Prado’s senior curator of Spanish painting (up to 1700), assembled a judicious selection of works from the permanent collection and interspersed them with a thought-provoking mix of less-expected works—including paintings by Manet, Sargent, Renoir, Picasso, Miró, Pollock, Motherwell, and Antonio Saura—as well as sculptures, publications, film, and photographs (those of the early museum were particularly fascinating).

Today, the Prado has become a different sort of pilgrimage destination, with annual visitors exceeding 3 million, and star status in Madrid’s increasingly tourism-based economy. With lines extending outside the museum and tickets regularly selling out, “A Place of Memory” displayed and also embodied the extent to which Spain’s artistic past has become a source of profound national pride as well as—quite literally—revenue.

In addition to “A Place of Memory,” the Prado has organized a miscellany of events celebrating its bicentenary, such as a show juxtaposing works by Velázquez, Vermeer, and Rembrandt; a reconstruction of the private chambers reserved for Spanish monarchs in the museum’s early years (including sumptuous his-and-hers toilets with mahogany veneer and yellow velvet cushions); and an exhibition of Goya’s drawings, presented in conjunction with the publication of the second volume of the catalogue raisonné of the artist’s drawings.

Goya—Madrid’s emblematic painter—was alive when the Prado opened in 1819, though that same year he purchased a small compound of buildings outside Madrid called Quinta del Sordo, where he lived in semi-seclusion. It was on the walls of the Quinta that Goya painted what would become known as the “Black Paintings,” dark and unsettling images that seem to flit between hallucinations and unbearable visions of humanity’s darker side. The paintings themselves were removed from the walls and transferred to canvas in the mid-19th century, and were later donated to the Prado before the Quinta was demolished in the early 20th century.

Earlier this year, Goya specialist Carlos Foradada ingeniously combined existing documentation from various sources—including a volumetric scale map and photographs from the 1800s, as well as letters and written documents—to construct 3D renderings of the Quinta’s architectural design. From that, he determined the distribution of the “Black Paintings” room by room. Based on specific sequences, Foradada developed a reinterpretation of the infamously elusive works in a book published earlier this year.

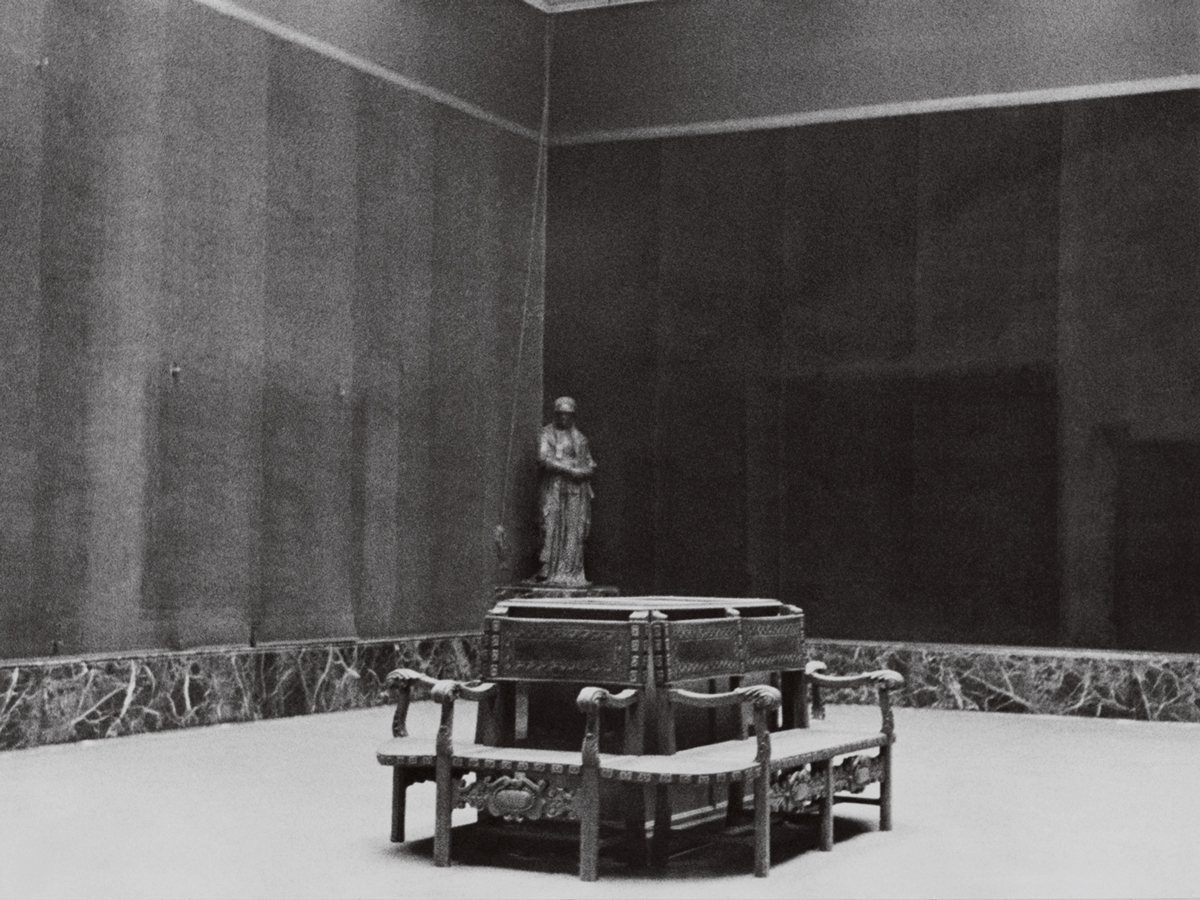

Installation view of “Armando Andrade Tudela: Self-Eclipse,” 2019, at Centro de Arte Dos de Mayo.

AURÉLIEN MOLE

According to Foradada, the “Black Paintings” were more directly rooted in the politics of their era than art-historical interpretation has generally allowed for, and they used extended allegories to portray contemporaneous conflict between Spain’s monarchical forces and the liberal, democratic (and ultimately doomed) reform movement. Goya, in Foradada’s estimation, was perhaps not so much haunted by psychic demons as by political disillusion—if not both at once.

One of Goya’s best-known Madrid paintings is the spectacular Dos de mayo, portraying the ill-fated uprising of civilian Madrileños against the French occupying army on May 2, 1808, a date that remains a holiday in Madrid. It also figures in the name of one of the region’s liveliest contemporary art centers, the Centro de Arte Dos de Mayo. Since opening in 2008, CA2M (as it’s otherwise known) has offered a platform for many of Spain’s more interesting emerging and mid-career artists, while also attracting artists from abroad. Recent exhibitions include “Self-Eclipse” by the Peruvian-born, France-based Armando Andrade Tudela.

Andrade Tudela’s work blends cultural commentary and historical awareness with a sculptor’s sensibility for volume, finish, and spatial interaction: “Self-Eclipse” activated all of these at once. The exhibition was presented as a kind of mise-en-scène. Visitors “entered” by stepping onto a raised platform (after donning protective slippers). The platform occupied nearly the entire exhibition space, which was covered with a glossy black material (hence the slippers). The space demarcated by the platform was additionally partitioned into a sequence of passageways and subdivided spaces.

Within the complex and striking staging were such objects as torqued metal modernist-like explorations of form-in-space, rough-hewn cast sculptures resembling paleolithic artifacts, garments, an antique tapestry (containing its own mise-en-scène), a feathered dream catcher, and more. The high-shine flooring reflected the overhead lights and created a sense of extreme depth, while the labyrinthine layout of the partitions flipped between back and front. The disorienting effect intensified the presence of the individual objects. Andrade Tudela’s masterful handling of perceptual slippage found a parallel in his handling of historical slippage, with the old and new not merely juxtaposed but handled so as to accentuate the internal rhymes and patterns that linked them within and outside the art museum’s cultural framing structure.

A number of other Spanish artists are integrating the past into their own idiosyncratic practices. Among them are Ibon Aranberri, Patricia Esquivias, Pedro G. Romero, and David Bestué. Earlier this year, Bestué presented a multipart intervention titled “Tramas” at CentroCentro, a contemporary art center that opened last year in one of Madrid’s most iconic buildings—the Palacio Cibeles, a grand wedding cake–style structure from 1919 near the Prado.

Though he has also published studies of Spanish contemporary architecture and design, Bestué is primarily a sculptor whose work often involves procedures of mutation and metamorphosis. He may, for instance, pulverize objects to try to extract their essential matter and then refashion that material into resin-based works centered on processes of compression and conflation—of past and present, fact and fiction, material and essence, form and signification.

Such facets of Bestué’s practice were on display in “Tramas,” an intervention in three parts: a didactic consideration of the building’s architecture, with texts, photographs, and architectural plans; a series of resin sculptures that referred to the building’s ornamentation, structure, and history; and a wallpapered melange of graphic design, photography and design. The disparate elements complemented the over-the-top nature of the building with a meshing of macro and micro concerns.

Cristina Lucas, Habla (Speak), still, 2008, HD video, 7 minutes. “Patriarchy,” Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum.

©CRISTINA LUCAS

The Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum also presented an exhibition earlier this year of artists using the past as materia prima for contemporary production. Titled “Patriarchy,” the show consisted of two videos: Speak (2008), by Cristina Lucas, and Mutual Dependence (2009), by Eulália Valldosera. The works shared certain elements—each presented a female figure interacting with a masculine statue—although the divergences were equally pronounced.

The statue in Speak is a plaster replica of Michelangelo’s Moses, and Lucas (as in the oft-told tale of Michelangelo himself) attacks it with a sledgehammer, demanding that it “speak.” She continues until all that remains is a pile of rubble, and the artist herself is depleted by her futile effort. Mutual Dependence also involves silence, but to a very different end. The video portrays a woman at the Archaeological Museum in Naples cleaning a seated statue of the Roman Emperor Claudius. Alternating between verité-style sequences of everyday museum routine and chiaroscuro close-ups, Mutual Dependence follows the woman’s increasingly erotic cleaning of the statue, with camerawork as caressing as the woman’s soft cloth. While the exhibition’s title and accompanying literature emphasized the element of feminist protest, the videos themselves spoke with complex voices, particularly through their silences.

The Thyssen-Bornemisza has also extended its collaboration with Thyssen-Bornemisza Contemporary (TBA21), the contemporary arts organization run by Francesca Thyssen-Bornemisza, the daughter of Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza, whose collection is the basis for the museum that bears his family name. Under the agreement, TBA21 will organize two exhibitions of contemporary art annually—such as the recent exhibitions of John Akomfrah and Amar Kanwar—and will be led by the recently named director of the foundation, Carlos Urroz.

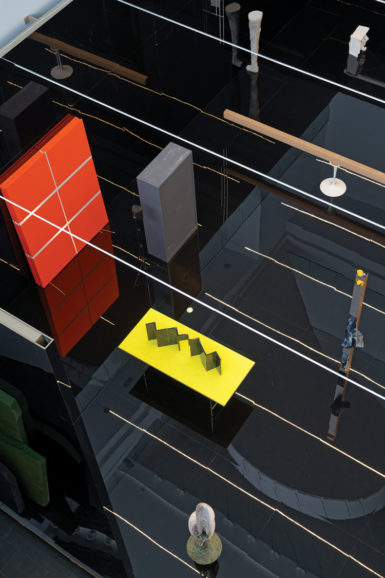

Installation view of “Bernardí Roig, Todos los icebergs son negros: Films 2000–2018,”2019, at Tabacalera.

COURTESY THE ARTIST AND GALERÍA KEWENIG

Another of Madrid’s more recently established art spaces is Tabacalera, a center specializing in photography and video, which earlier this year exhibited the work of Spanish artist Bernardí Roig in “Todos los icebergs son negros: Films 2000–2018.” Roig is a mid-career multimedia artist known primarily for figurative sculptures and installations, but the show focused instead on his work with film and video, presenting some 20 short, generally black-and-white, non-narrative works.

Like his sculpture, Roig’s moving-image works are obsessively angst-ridden, with such recurring images as severed heads, human-animal-technology hybrids, and sadomasochistic eroticism. Built in 1792, the structure housing Tabacalera served as a tobacco factory (tabacalera, in Spanish) into the 20th century before falling into disuse. Today it is vast and very dark—an ideal setting for Roig’s macabre vision, demonstrating the charged presence of the past in Madrid’s present-day art world.

A version of this story originally appeared in the Summer 2019 issue of ARTnews on page 102 under the title “Around Madrid.”

[ad_2]

Source link