[ad_1]

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Bird On Money, 1981, acrylic and oil on canvas.

COURTESY RUBELL FAMILY COLLECTION, MIAMI

“30 Americans,” an exhibition of works by African-American artists from the Rubell Family Collection in Miami—ranging from then-emerging talents like Rashid Johnson to established ones like Kara Walker and historical figures like Robert Colescott and Jean-Michel Basquiat—has been traveling to institutions across the United States for 10 years, an unusually long time for a multi-venue show. This coming weekend, it opens at the Barnes Collection—the 17th stop on its tour. On the occasion of its decade on the road, the Barnes commissioned from the exhibition’s curator, art historian Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw, an essay looking at its wide-ranging effect, both within the art world and in the culture at large. Below is an excerpt from that essay. —The Editors

Since its December 2008 premiere at the Rubell Family Collection in Miami, “30 Americans” has become the most viewed exhibition of its kind. Curated from the extensive holdings of contemporary art owned by the Rubell family, the exhibition includes works by 31 African American artists who explore contemporary social issues and personal mythologies through various modes of abstraction and diverse representational strategies. Because these artists occupy complex subject positions, to say that they share a common identity as African Americans belies the richness of their varied and often intersectional experiences as men, women, straight, gay, queer, wealthy, working class, and so forth. Just as there is no single type of work in this exhibition, which includes sculpture, painting, video, and installation, neither is there one kind of “Black” artist in the group.1

Along with the diversity of the work included, a major attraction of “30 Americans” has been its rarity. Important exhibitions of challenging contemporary art that reflects or interrogates the lived realities of being non-white, queer, or working class in our society are rarely shown by mainstream museums. Over the past century, as museums in this country filled their galleries and storage vaults with works of art, their mostly white and mostly male leadership has consistently failed to acquire work by minority and women artists. Recent studies have shown that most major museum collections in the US contain just a small percentage of works by artists who are white women or people of color or who openly represent LGBTQ+ communities.2 Regardless of their institutional holdings, most museums that purport to serve general audiences rarely have more than a few works by such artists on view, and if museumgoers are not already familiar with the backgrounds of those artists, that diversity might go unnoticed. Not surprisingly, curious and excited audiences from all backgrounds and walks of life have flocked to see “30 Americans,” and their enthusiasm has translated to record attendance. Well over one million viewers have seen this exceptional exhibition.

At each venue in which “30 Americans” has been shown, the exhibition has been rethought and reinstalled according to the spatial limitations of the hosting institution and the professional judgment of the curatorial team. An exhibition that could include as many as 260 works of art from the Rubells’ collection has in many venues featured as few as 50. At the Chrysler Museum in Norfolk, Virginia, the organizing curators interspersed works from the museum’s own permanent collection among those from the original checklist.3 Similarly, the curators at the Cincinnati Art Museum dispersed the show throughout the museum’s galleries as a way to lead visitors through the space as a whole and to highlight the museum’s own holdings of works by Lorna Simpson, Glenn Ligon, and Nick Cave.4

Nick Cave, Soundsuit, 2008, fabric, fiberglass, and metal.

COURTESY RUBELL FAMILY COLLECTION, MIAMI

By the time that “30 Americans” arrived in Detroit in 2015, the rarity of exhibitions of contemporary art by Black artists at the Detroit Institute of Arts had become a major issue for the local art community. The city’s population is 80 percent Black, and despite General Motors’ endowment of a center for African American art at the museum nearly two decades earlier, DIA had been perplexingly hesitant to embrace the needs of its largest racial and ethnic demographic. “The museum has failed to capitalize on what it has [locally],” George N’Namdi, founder of the N’Namdi Center for Contemporary Art in Detroit and a prominent dealer of African American art, told the Detroit Free Press. “This was one of the major collecting spots in the country for African-American art. The museum should be a leader in this area for the population that’s here, and because it could really distinguish itself in this area.”5

Thankfully, the arrival of “30 Americans” at DIA lent support to the longstanding efforts of Valerie Mercer, curator of the General Motors Center, to expand the institution’s collection of art by Black artists. Attendance for the exhibition was 16 percent higher than the museum’s original target, and African American visitors made up 41 percent of the total.6 These numbers went a long way toward convincing the museum’s leadership that a greater commitment to African American art would diversify the museum’s audience and help DIA establish itself as a visibly progressive force in the Motor City. In 2016, the museum launched a formal initiative, spurred by a contribution from the Ford Foundation, to redress the absences in its collection by purchasing works of art by African American artists. “Museums today are about more than just art on the walls,” Ford Foundation president Darren Walker told the Free Press. “The best museums today take seriously the responsibility to build communities. Museums should educate and empower the citizenry, and nothing is more empowering for African Americans than seeing great art by African Americans on the walls of a museum like the DIA.”7

Other venues for the exhibition have also seen their collecting and exhibiting programs influenced by what I call the “30 Americans effect.” Linda Johnson Dougherty, chief curator and curator of contemporary art at the North Carolina Museum of Art in Raleigh, has said the exhibition had a “huge impact” on their collection, which now includes works by Mickalene Thomas, Kehinde Wiley, Hank Willis Thomas, Purvis Young, and others. She also credits “30 Americans” for the museum’s upcoming solo exhibition of Leonardo Drew.8 Similarly, the Joslyn Museum in Omaha, Nebraska, moved to purchase works by Thomas, Wiley, Kara Walker, and Rashid Johnson within months of the show’s opening there in the winter of 2019.9

If museums have sat up and taken notice since “30 Americans” came on the scene, then the secondary art market and the collecting world have been standing at attention when it comes to many of the artists included in the show. In the years immediately preceding the organization of “30 Americans,” the secondary art market had already begun to recognize the investment value of works by Jean-Michel Basquiat, for example, when one of his paintings fetched a record-setting $14.6 million at a 2007 auction. A decade later, auction prices for Basquiat paintings had risen dramatically. In May 2017, Untitled (1982) garnered an astronomical sum of $110.5 million.10 In 2014, one of Glenn Ligon’s white text paintings sold for $3.9 million, while a piece by David Hammons garnered $3.5 million. In March 2018, Mark Bradford’s Helter Skelter I (2007) set a record auction price for a work by a living African American artist when it sold for nearly $12 million.11 That record was soon broken in May of the same year, when Kerry James Marshall’s epic painting Past Times (1997), below, sold for $21.1 million.

With his purchase of Past Times, rapper and hip-hop producer Sean “Diddy” Combs joined a growing group of Black music industry titans who are increasingly focused on collecting contemporary African American art as a cultural statement and financial investment. Producer Kasseem “Swizz Beatz” Dean and his wife, the pianist and vocalist Alicia Keys, have collected more than 400 pieces—many by “30 Americans” artists such as Mickalene Thomas, Nina Chanel Abney, and Kehinde Wiley—putting the couple at the forefront of this movement.12 And while Swizz Beatz has become well known for his interest in collecting and promoting Black art, Beyoncé Knowles Carter and her husband, Shawn “Jay-Z” Carter, have been the most publicly visible and broadly influential members of the hip-hop aristocracy to make themselves a part of the African American contemporary art scene.

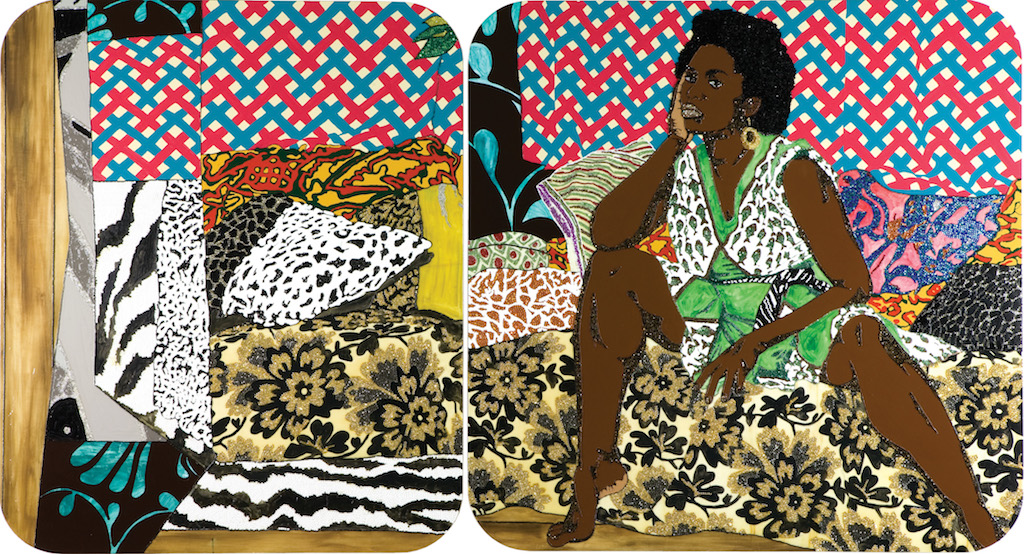

Mickalene Thomas, Baby I Am Ready Now, 2007, diptych, acrylic, rhinestone and enamel on wooden panel.

COURTESY RUBELL FAMILY COLLECTION, MIAMI

In addition to collecting art, the Carters have shared numerous photographs of themselves with works of art, and they allude to art history on their social media accounts and in their creative product. Their 2014 Halloween costumes—where Beyoncé dressed as Frida Kahlo and Jay-Z went as Jean-Michel Basquiat—created a significant buzz, as did an image of Beyoncé mimicking a Kerry James Marshall painting on exhibition at David Zwirner Gallery in London. Beyoncé’s 2014 video for the song “7/11” has her dancing around her living room with a David Hammons basketball drawing in the background, revealing a glimpse of how the couple lives with their art collection.13 And in 2013, when Jay-Z shot a performance art–inspired video for his song “Picasso Baby” on location at Pace Gallery in New York, he invited a number of contemporary artists of African descent, including Fred Wilson and Jacolby Satterwhite, to participate. In 2018, working together under their married name, the Carters arranged to shoot the video for “Apeshit”—an infectious ode to fame, good taste, and success—in the Louvre Museum in Paris. Over the course of a remarkably brisk six minutes, the gloriously decked-out couple poses amid the Hellenistic Nike of Samothrace (190 BC) and the Venus de Milo (101 BC), while groups of beautifully diverse Black dancers execute routines in front of iconic works of art, including Leonardo Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa (1503), Théodore Gericault’s The Raft of the Medusa (1818–1819), and Marie-Guillemine Benoist’s Portrait of a Black Woman (1800). Interwoven into these shots are cutaways to young Black models whose intricate poses echo the works around them in highly contemporary tableaux vivants. One senses the influence of Kehinde Wiley’s painting practice in this final gesture of co-optation and signification. The immensely popular video was viewed more than 150 million times in its first 12 months of release, and the Louvre saw a 25 percent increase in attendance from 2017 to 2018.14 In response, the museum began offering a 90-minute tour that included all the works of art featured in the video.15 Through their exuberant embrace of art in their public and private lives, the Carters have leveraged their towering influence to bring more attention to contemporary Black artists and their work.

In addition to changes in the art market and the collecting habits of hip-hop royalty, the influence of “30 Americans” can be seen in the visually prominent yet entirely fictional collection of art owned by the music mogul Lucious Lyon on the Fox television show Empire. The serial melodrama, which debuted in 2015 and is slated to enter its sixth and final season in 2019, focuses on a highly successful and ridiculously stylish family of African American musicians, producers, and entrepreneurs. Remarkably, contemporary African American art is as much a part of the show’s vibe as the musical interludes and fashionable clothing that distinguish its characters’ lives from other primetime fare. The artworks shown in the background of scenes present viewers with a who’s who from the roster of “30 Americans.” And while immediately recognizable works by Mickalene Thomas, Kehinde Wiley, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Barkley L. Hendricks, and Kara Walker have been featured on Empire, works by other artists not in “30 Americans,” such as Jamea Richmond-Edwards and Michael Savoie, have gained considerable exposure by being in their company. By spotlighting real-life works of art— present on set in the form of high-quality facsimiles—Empire has helped to make contemporary art by African American artists increasingly visible in American popular culture.

Excerpt from an essay originally published by the Barnes Foundation. ©2019 The Barnes Foundation.

Endnotes

1. A note on terms. Throughout this essay, I use “Black” and “African American” to refer to peoples of African descent born or living in the US. You will also see the terms “black” (without capitalization) and “African-American” (with a hyphen) used by other writers. While I have preserved the original style of these terms for citational accuracy, my preference is for “Black,” which implies a broadly, but not monolithically, shared ethnic identity, like Jewish; and for “African American,” which emphasizes the temporal and continental bridging that bodies of people of African descent represent in contemporary American life (and grammatically, I do not feel that the hyphen is necessary).

2. Chad Topaz et al., “Diversity of Artists in Major U.S. Museums.” PLoS One, March 20, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0212852.

3. “30 Americans Surveys African-American Artists over Three Decades.” Artfix Daily, March 1, 2012.

4. Maria Seda-Reeder, “Exhibit Navigates Life Via Black Artists’ Eyes.” WCPO.com, March 18, 2016.

5. Mark Stryker, “DIA Launches Multimillion-Dollar Effort to Acquire African-American Art.” Detroit Free Press, July 20, 2016.

6. Carey Dunne, “Detroit Institute of Arts Launches Initiative to Deepen Collection of African American Art.” Hyperallergic.com, July 28, 2016.

7. Mark Stryker, “DIA Launches Multimillion-Dollar Effort to Acquire African-American Art.” A similar grant from the NEA was used by the MFA Boston to increase its holdings of art by historically under-represented artists. Today, those funds and others raised by the museum are part of its Heritage Fund, which encourages various departments to pursue the purchase of works made by more racially and ethnically diverse artists from the US.

8. Email between author and Juan Roselione-Valadez, director of the Rubell Family Collection, August 7, 2019.

9. Email between Juan Roselione-Valadez, director of the Rubell Family Collection, and Karin Campbell, Phil Willson Curator of Contemporary Art, Joslyn Art Museum, June 21, 2019.

10. Basquiat’s Untitled (1982) was purchased by Japanese entrepreneur Yusaku Maezawa at Sotheby’s evening auction for $110.5 million.

11. Helter Skelter I sold for £8.67 million, about $10.4 million (nearly $12 million, including fees), at Phillips London on March 8, 2018.

12. M. H. Miller, “How Swizz Beatz Bridged the Worlds of Hip-Hop and Contemporary Art.” The New York Times Style Magazine, February 13, 2019.

13. “Who Does Beyoncé Collect? See the Queen Bey’s Fierce Art Collection.” Artspace, February 23, 2018.

14. Kristin Corry, “Beyoncé and Jay-Z Helped the Louvre Break Attendance Records.” Vice, January 4, 2019.

15. Francesca Street, “The Louvre Launches Beyoncé and Jay-Z Tour.” CNN, July 11, 2018.

[ad_2]

Source link