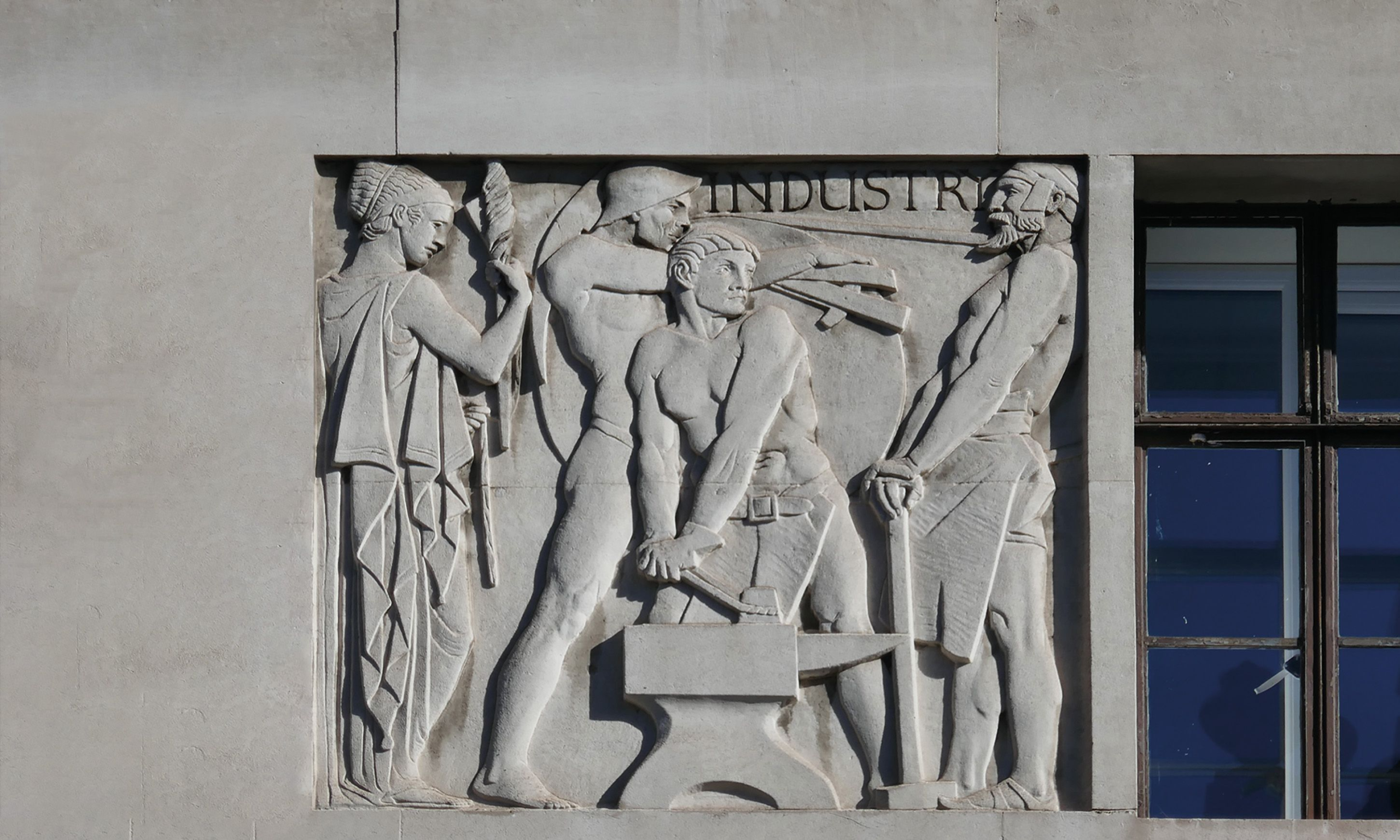

Industry, one of Gilbert Bayes’s “superb” reliefs on James Miller’s Commercial Bank of Scotland, Glasgow (1935) Photo: Roger Edwards

Public sculpture comes in for a hard time these days as the butt of self-righteous onslaught. It used to be generally overlooked, unless it fitted in to the standard narrative of the rise of Modernism, like Jacob Epstein’s battered figures on the British Medical Association building on the Strand, which caused Edwardian London to gasp in ribald perplexity on their unveiling in 1908. Eric Gill’s 1932 figures on the exterior of the BBC’s Broadcasting House were attacked in 2022 and 2023 as the work of a paedophile; and in Cardiff, the statue of the controversial Waterloo hero General Thomas Picton has been removed from within the splendid City Hall (1900-04) by Lanchester, Stewart and Rickards.

John Stewart’s survey of the rise and fall of architectural sculpture between the Great Exhibition and the Festival of Britain is, therefore, timely and contains much of interest. Gill had been brought in to enhance the austere flanks of Broadcasting House as a way of furthering the Reithian mission of bringing high culture to the masses: sculpture embodied the great tradition of classicism and could embody historical, literary and allegorical messages. Gill had his doubts: sculptors, he declared, were “called in by the architect to titivate a building which, it is supposed, would otherwise be too dull or plain” by creating art that “proclaims who the building belongs to and what game they think they are playing at”. Architectural sculpture is an obvious conveyer of ideology. Stewart explains well how the teetering Port of London Authority building at Tower Hill (1912-22) expresses London’s relationship to the Thames as the gateway to the Empire beyond, and it is a shame the group at Glasgow’s Kelvingrove Art Gallery, The Empire Salutes Glasgow, is not illustrated. But it is not all imperial bombast or civic swagger: the reliefs of boozing monks within the Black Friar pub are crucial to the success of London’s most engaging Art Nouveau interior.

Stewart (a Scottish architect) takes us chronologically through the shifting relationships of architects with sculptors, explaining how their status rose from lowly artisan to respected co-creator, a process embodied in the formation of the Art Workers’ Guild in 1884. Richard Norman Shaw urged fellow architects to “knock at the door of art”, and the period up to the outbreak of war in 1914 witnessed a flourishing of partnerships across the arts: John Dando Sedding and Henry Wilson working closely on London’s Holy Trinity Church on Sloane Street; Aston Webb and Harry Bates at the Birmingham Law Courts; and William Young and Alfred Drury at the Old War Office on London’s Whitehall. This latter work dates from 1898 to 1906, the zenith of British global reach: but its sculptural groups include The Horror of War replete with a menacing skeleton. There was more to this field than unthinking jingoism.

Some schemes get more attention than others. John Belcher’s Chartered Accountants’ Hall (1889-93)—at Moorgate Place, London—rightly comes under the spotlight for its friezes by Hamo Thornycroft, but London’s Deptford Town Hall (1903-05) by Lanchester, Stewart and Rickards, important for its opulent naval embellishment by Henry Poole, is omitted—it was recently the subject of a consultation to decide whether the naval statues should be cancelled. These buildings were conceived as unities of the arts in which carved elements were intrinsic to the overall effect. Stewart similarly swerves around the issue of Henry Pegram’s statue of Cecil Rhodes on Basil Champneys’ frontage to Oriel College, Oxford. It is unfair to lament omissions in a book that covers much ground, but it is a shame to ignore Waterloo Station’s Victory Arch—the finest war memorial on a building—or Gilbert Bayes’s relief Drama through the Ages on London’s Saville Theatre, although one of his superb friezes for the Commercial Bank of Scotland in Glasgow (1935) depicting Industry illustrates the front cover. Nor is there much about churches.

Stewart is at his best in chronicling the architectural developments of the age; sometimes sculpture-free buildings get mentioned, suggesting mission creep. One of the big themes in the book is the challenge of modernism, and its hostility to three-dimensional distraction, instanced by three London schemes: Grey Wornum’s RIBA Headquarters (1932-34) is cited as a late instance of the fusion of building and sculpture; Walthamstow Town Hall (1937-42) is rightly mentioned for John Kavanagh’s powerful figures. Henry Moore’s early 1950s work on the Time-Life Building in Bond Street closes the narrative. The epilogue ends on a doubtful note, seeing the integration of architecture and sculpture as surviving only in Classical revivalism, where Sandy Stoddart’s work with Craig Hamilton is singled out. Overall, this is a welcome book on a fascinating topic. As Gill quipped, what game did they think they were playing at?

• John Stewart, British Architectural Sculpture 1851-1951, Lund Humphries, 208pp, 151 colour illustrations, £45/$89.99 (hb), published 3 May/22 August

• Roger Bowdler is a partner at Montagu Evans, advising owners on historic buildings. He was Director of Listing at Historic England and writes on funerary art