[ad_1]

Douglas Crimp.

KATHERINE MCMAHON/ARTNEWS

Douglas Crimp, who penned some of the most important art-historical essays of the second half of the 20th century, including “Pictures” and “On the Museum’s Ruins,” has died at age 74. A representative for the University of Rochester’s art history department, where Crimp had long served as professor, confirmed his death.

Crimp’s influence has been vast. His writings explored a vast range of topics, from image circulation to institutional critique to art and AIDS. It has become impossible to write the history of postmodern art without referring at least once to his criticism.

Perhaps Crimp’s most important essay is “Pictures,” which was first published in 1977 to go alongside an exhibition of the same name at Artists Space in New York. (A second revised and expanded version—the essay’s more famous iteration—was published in the journal October in 1979.) Drawing on emergent French philosophy, “Pictures” theorized a kind of art that dealt with the nature of images themselves—Crimp’s focus was not what a picture portrayed so much as what a picture did once it was released into the world. His concern, in other words, was not what pictures are, but what pictures do.

“Such an elaborate manipulation of the image does not really transform it; it fetishizes it,” Crimp writes of a tendency found among New York–based artists during the 1970s. “The picture is an object of desire, the desire for the signification that is known to be absent.” He goes on to suggest that traditional understandings of authorship were being tested.

[Read ARTnews’s review of “Pictures” at Artists Space.]

The artists Crimp discussed were Troy Brauntuch, Jack Goldstein, Sherrie Levine, Robert Longo, and Philip Smith; to them, Crimp added Cindy Sherman for the essay’s second version. All sought to peel back the ways we understand photography and reproduced imagery in a time of mass-media consumption. The artists’ interests were outwardly intellectual and conceptual; theirs was a rigorous way of working and thinking, and Crimp reflected it through a reliance on post-structuralist theory, which explored how the significance of ideas and objects was tethered to larger systems of thought and representation.

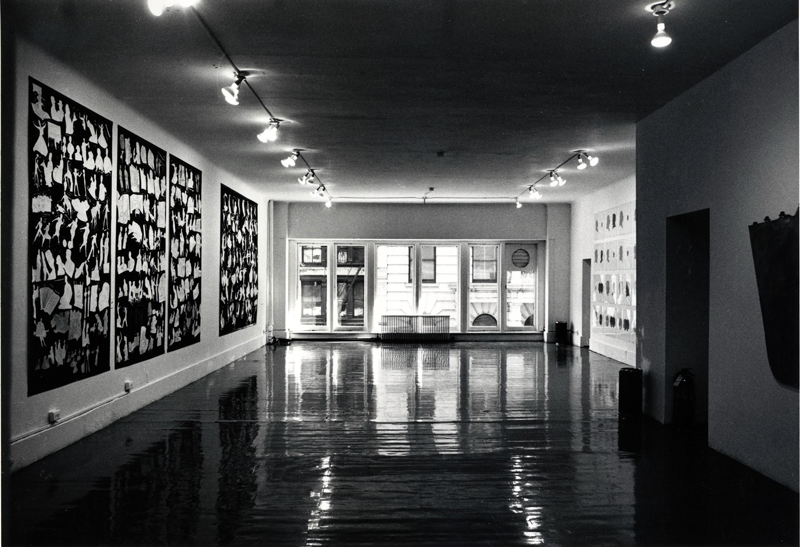

Installation view of “Pictures,” 1977, at Artists Space, New York.

©D. JAMES DEE/COURTESY ARTISTS SPACE, NEW YORK

At the time, Sherman was developing one of the most notable photographic series of the 20th century—the “Untitled Film Stills,” for which she posed in a variety of settings that recall noirish plots and domestic melodramas. Her photographs have no narrative, and yet we are able to concoct stories that encapsulate her images just by looking at them—that’s how pervasive the female stereotypes she portrays have become in films, ads, and magazine spreads. Louise Lawler, an artist addressed in other writings by Crimp, explored the nature of objects in museums, photographing artworks mid-install and arranging imagery that she would then exhibit as pieces unto themselves.

These sly, icy strategies for creating photography about photography were formalized through “Pictures,” and the artists have since become known as the Pictures Generation—the subject of a 2009 exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. The essay’s influence can also be seen beyond that core group of artists, in the work of Dara Birnbaum, Christopher Williams, Barbara Kruger, Laurie Simmons, and many more.

[Read a 2016 conversation with Douglas Crimp.]

Lawler’s photographs were integral to one of Crimp’s most famous books, On the Museum’s Ruins (1993), whose title essay from 1980 is considered an urtext for a tendency known as institutional critique, which focuses on museums and power dynamics. In that essay, Crimp writes on how modernism gave way to the current museological condition, in which anything shown in a museum setting is deadened, fixed in time, and immediately placed into art history.

For the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century, painting was considered the most important medium, but, Crimp theorizes, the methods of displaying objects in museums changed and effectively killed it. Photography, he suggests, was essential in this process—the medium “began to conspire with painting in its own destruction,” he writes. Then, at the essay’s end, he brings his subject matter full circle. Photographs, when exhibited in museums, get killed, too. The 1993 book that includes the essay features photographs by Lawler that show sculptures in storage. They are sheathed in plastic, and through her camera’s lens, the objects look a bit like cadavers.

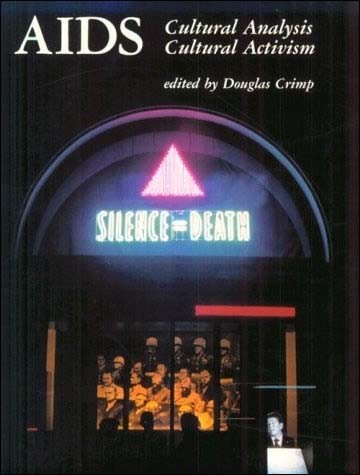

There was a political streak to some of Crimp’s work as well, and he has been considered a critical figure in the formulation of a queer aesthetic during the start of the AIDS crisis, in the late 1980s and early 1990s. In 1987 Crimp was invited by October, where he served as an editor between 1977 and 1980, to do an entire issue about art and AIDS. Titled “AIDS: Cultural Analysis/Cultural Activism,” the issue is regarded as a watershed document of its era, and as one of the landmark editions of a journal that, at that time, tended toward less outwardly political content.

Importantly, “AIDS: Cultural Analysis/Cultural Activism” did not focus only on art—it also dealt with activism. Crimp has discussed how he began attending meetings held by ACT UP, a group that aimed to raise awareness about AIDS, which at the time was written off or disregarded by the general public, and how he wanted to do the issue as an extension of these activities.

COURTESY THE MIT PRESS

“People were blind to the reality of what was going on, and I knew that this would get people thinking,” Crimp said in a 2008 interview. “I knew who read October, and it wasn’t people in the AIDS movement, except in so far as a lot of people in the AIDS movement were also people studying in the Whitney Program—young art world people. But in general the readers of October wouldn’t expect something like the AIDS issue. It got a lot of attention.”

In the years following October’s AIDS issue, Crimp wrote frequently about queerness. He began encouraging artists to take a more activist stance, and in 1990 he said, “The aesthetic values of the traditional art world are of little consequence to AIDS activists.”

In a 1989 essay called “Mourning and Militancy,” which is dedicated to artist Gregg Bordowitz, Crimp called on gay men in his community to be vocal about the difficulties they face. (He acknowledged that AIDS affected more than just gay men, but argued that they were the ones hit hardest by the epidemic.) Crimp writes, “Frustration, anger, rage, and outrage, anxiety, fear, and terror, shame and guilt, sadness and despair—it is not surprising that we feel these things; what is surprising is that we often don’t. . . . To decry these responses—our own form of moralism is to deny the extent of the violence we have all endured; even more importantly, it is to deny a fundamental fact of psychic life: violence is also self-inflicted.” A book of his writings on AIDS and queer politics was compiled by the MIT Press in 2002.

Issues of queerness and identity were central to his career from its very start. In his 2016 memoir Before Pictures, which focuses on his life prior to curating “Pictures,” Crimp writes of Max’s Kansas City, the storied New York nightclub that was frequented by both the art world and the queer community. The two had little contact and remained confined to different parts of the nightclub. “The division represented by Max’s front and back rooms—between the art world and the queer world—was one that I would negotiate throughout my first decade in New York City,” Crimp writes.

[Read a review of Before Pictures.]

Crimp was born in Coeur d’Alene, Idaho, in 1944. Having studied art history at Tulane University in New Orleans, he came to New York in 1967. He arrived at a rich time in the city’s cultural history—Allan Kaprow’s happenings may have been a decade in the past, but their impact still lingered, and artists were enjoining themselves to a variety of epicenters of the avant-garde, including the Fluxus group and the Judson Dance Theater.

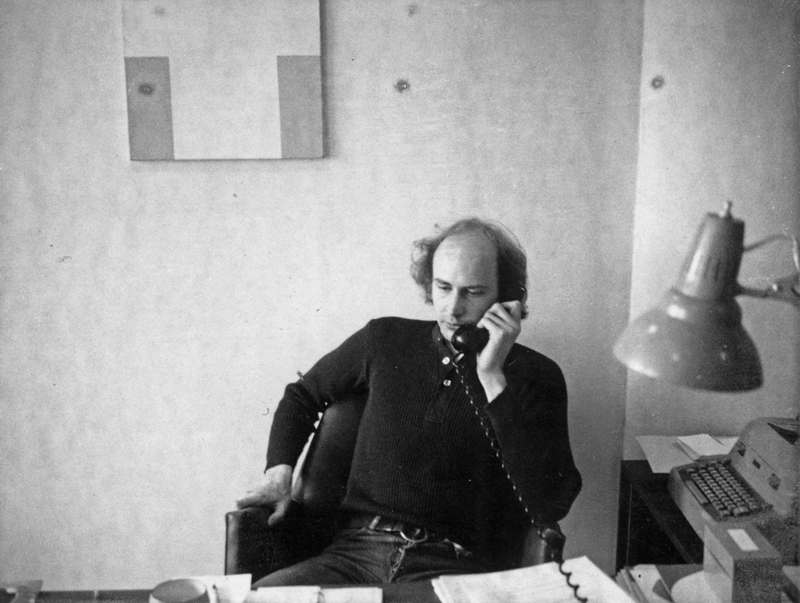

Douglas Crimp at the Guggenheim Museum in 1970.

COURTESY DANCING FOXES PRESS

By his own admission, his arrival in New York was born of his naiveté. “My only knowledge of New York was through reading—ARTnews and Art in America,” he told ARTnews in 2016. “I had never seen a proper exhibition until I moved to New York.”

Nevertheless, Crimp quickly became an integral member of the New York art world. He became a curatorial assistant at the Guggenheim Museum in New York, and he went on to teach at the School of Visual Arts, for whom he curated an exhibition of Agnes Martin’s work. In the 2016 ARTnews interview, Crimp described being mentored by Diane Waldman, a Guggenheim curator, and Elizabeth C. Baker, who served as this magazine’s managing editor during the early 1970s. (Crimp also wrote reviews for ARTnews at the time.)

Though Crimp is best known for his writings, he also curated several notable exhibitions beyond “Pictures.” In 2010, for the Museo Reina Sofía in Madrid, with Lynne Cooke he organized “Mixed Use, Manhattan,” an exhibition that surveyed photography as it related to the ways artists relied on spaces around the city, and he worked on the 2015 edition of MoMA PS1’s Greater New York quinquennial.

Barbara Schroeder, an editor at Dancing Foxes Press, said that the publishing house is currently working on Dance Dance Film, a book of Crimp’s writings on dance and film that focuses on Charles Atlas, Trisha Brown, Merce Cunningham, Tacita Dean, Anne Teresa de Keersmaeker, Yvonne Rainer, and more. “Douglas’s devotion to dance and film is well known to so many, and he was thrilled, as we are, at the prospect of the publication of this collection,” Schroeder said. “We will dearly miss Douglas’s sharp intelligence and distinctive voice.”

In his ARTnews interview in 2016, Crimp said that the art world had changed vastly since “Pictures” was penned. It had grown significantly larger, and it was being injected with huge amounts of money. But he urged readers to “continue to inhabit a world in which art matters in the way that it has mattered to me all along.” This kind of art, he said, “challenges us, it makes us think differently; it takes us outside of ourselves.”

[ad_2]

Source link