[ad_1]

Tom Steyer is a study in contrasts.

The California billionaire who will make his national political debut next week in the fourth Democratic primary debate is one of the nation’s richest men, but has turned up to West Coast political meetings in outfits that, as one observer put it, “couldn’t have cost more than $150 in total.”

He is a reverent Christian who has been known to drag his older brothers to church on Sundays, but doesn’t hesitate to unleash a string of expletives in front of a reporter if the moment demands it — even to quote his own mother.

In person, Steyer is lighthearted and playful – given to modest rituals, colorful beaded belts and easy laughter — but can turn deadly serious in a second’s span and has enough money to pose a threat to every single Democratic candidate in the crowded primary field.

One of the largest single donors in the entire 2016 election cycle, he has pledged to spend $100 million on his own campaign – his first ever run for public office. No single American has spent as much money in the past decade on the American political system as Steyer.

Yet he can surprise when least expected.

At the start of a campaign stop in Philadelphia last month, one of America’s wealthiest men called out to a young campaign aide just before entering a retail store on a rundown strip along South 9th Street.

“Hey Luis, you got any money?”

“We shouldn’t go into these stores and not buy anything.”

A long line of well-heeled, would-be presidents have sought the White House, banking on their money overcoming a lack of name recognition or raw experience in retail politics, and fallen short — at times spectacularly. But Steyer, a billionaire and Democratic mega-donor, is trying to become the first to test whether President Donald Trump’s electoral success in 2016 has changed that calculus.

In a wide-ranging interview with ABC News which touched far more on the personal than the political, Steyer spoke at length about his faith, his fortune, his quirks and his passions.

Chris Francescani/ABC News

Chris Francescani/ABC News

Party priorities

In a wildly-unpredictable Democratic primary, his supporters believe Steyer could penetrate the field with his sense of candor and a track record of extraordinary financial success.

Steyer’s success in the race itself may ultimately depend on whether voters relate to an unconventional coastal liberal with a distinct California sensibility.

The long-shot candidate’s wealth spent on political ad campaigns and various networking efforts have helped him stay afloat, though he remains ranked among the bottom tier of candidates who will take the stage for next week’s debate.

Critics on both sides of the aisle harbor deep doubts about Steyer’s viability.

“I don’t think he has a prayer,” said Republican political strategist Alex Castellanos, an ABC News consultant. “Steyer thinks he’s a Democratic party leader because they take his money, but he is a rich white male in a party that hates rich white males, a party that’s embarrassed by wealth.”

“Since religion is important to him, maybe I can say this,” Castellanos said as he prepared to paraphrase a famous quote from the Bible. “It’s easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle, than for a rich man to gain the Democratic nomination for president.”

“If you were, say, a tech billionaire — you might have a better shot today,” the Republican strategist continued. “Steyer made his money buying and selling money, investments. He didn’t invent the future. Had he invented the future like some tech wizards, that might have given him a lane, but he didn’t invent the future. He exploited the past — capitalism — what Democrats are trying to leave behind.”

After spending several years in the late 1970s and early 1980s at Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs in New York, Steyer and financier Warren Hellman founded a San Francisco hedge fund, later named Farallon Capital, which grew from managing $15 million at the start to $20 billion today, and where he built his fortune by making high-risk investments in distressed assets. He retired from the firm in 2012 and turned his attention to the environment and a host of liberal political issues in his home state of California.

Steyer has been criticized for making carbon-polluting investments during his time at Farallon — and then for not divesting of them fast enough. It’s an issue that can still rankle him.

“People always say to me, ‘are you sorry you invested in fossil fuels?’ And I’m like, ‘We invested in everything.’ Am I sorry that I realized it had this horrible issue with it? Do I wish I realized it earlier? Yes. Of course I do. Thank you. I wish I were smarter. Thank you. I didn’t realize it would be better if I were smarter. Thank you for bringing it up!'”

While he has said that Farallon is completely divested of fossil fuel-related investments, a 2014 New York Times examination of his investments concluded that the investments his firm made in coal-related projects will continue to generate tens of millions of tons of carbon pollution for years.

Steyer has also said he “deeply regret[s]” a $34 million investment in 2005 in a for-profit prisons firm called Corrections Corp. of America, which runs migrant detention centers on the U.S.-Mexico border, which have come under sharp criticism by Democratic presidential candidates this year.

The San Francisco political financier is betting that the urgency of the climate change crisis will minimize these points from his past as financial footnotes, but even some California Democrats are skeptical.

ABC

ABC

“The way that these billionaires make their money may be perfectly acceptable and understandable in the business community itself, but when you try to parlay that into a Democratic campaign, a lot of that is going to come back and haunt you,” said West Coast political consultant Garry South.

“You’re dealing with Democratic primary base voters, not Republican base voters,” South said. “To have a candidate come along and say, ‘I can run a business’ — that’s not a compelling argument to Democrats. They’re highly suspicious of business.”

‘CEO temperament’

Steyer has been involved behind-the-scenes in progressive California politics for more than a decade.

In the past two years, Steyer has also spent more than $10 million on television and digital ads calling for President Trump’s impeachment.

He has flirted with public office before, but never formally run. He had been contemplating running to win the California governorship in 2018, but stepped aside in deference to his friend, current California Governor Jerry Brown — though a sense of frustration over that race appears to linger within the Steyer family.

“Tom’s a CEO [chief executive officer] by temperament, so, you know, being the junior senator from California didn’t have all that much appeal to him,” said his brother Hume, a New York attorney. “And [California] governor made a lot more sense to him, but Jerry Brown was smack-dab in the middle of a run. Now, was Tom disappointed that Gov. Brown decided to run at the age of 116 for a third term? Yeah, I would say so.” (Brown is actually 81). “But they’re friends and he wasn’t going to get in the way.”

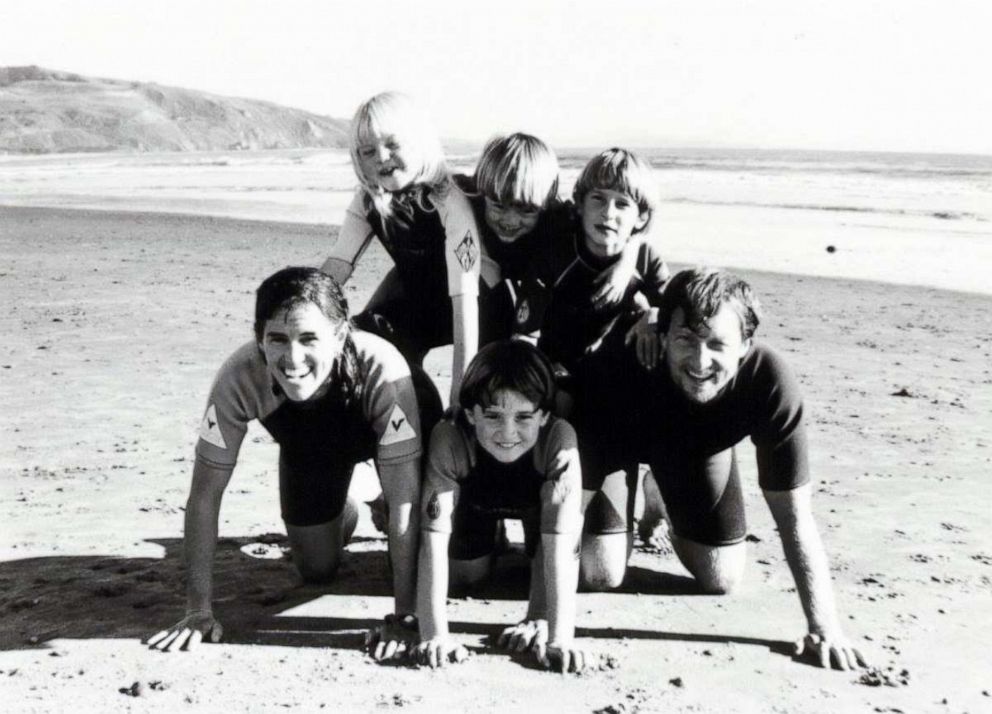

Tom Steyer campaign

Tom Steyer campaign

Green roots

Steyer’s central issue is combating global warming, and his presence in next week’s debate could shake up a field that has only recently began issuing detailed climate change action plans.

And just months ahead of the Iowa caucuses, his signature issue is gaining ground nationwide.

A Washington Post/Kaiser Family Foundation poll released last month found that 8 in 10 Americans believe that human activity is fueling climate change, and more than half believe that urgent action is needed within the next decade.

A longtime fundraiser for the Democratic party, Steyer first got formally involved in environmental politics in 2010 when he teamed up with Republican former U.S. Secretary of State George Shultz at the helm of a successful campaign to stop California’s Proposition 23, which preserved the state’s landmark initiative to fight global warming — and was the campaign’s single largest individual donor.

But his passion for the outdoors may have began much earlier, said his brother Jim, a Stanford University political science professor.

The three Steyer brothers — Hume, 65, Jim, 63, and Tom, 62 — spent their early childhood visiting their mother’s family in Minnesota, and went on to spend four summers at Camp Treetops in the Adironacks.

“No competitive sports – it was all mountain climbing and hiking and gardening and canoeing,” said Jim Steyer, who lives near his brother Tom in San Francisco. “At Camp Treetops we had to eat all that sh—ty stuff from the garden and milk cows and take care of horses when we were little,” he recalled fondly. “And I think that institution really impacted us,” he continued.

Steyer’s other brother, Hume, said their mother and father were anything but helicopter parents.

“If you’re asking me if Tom’s passion comes from my parents, I’m not sure I’d attribute these qualities [to them] as such,” Hume Steyer said in a recent interview. “My parents parented with a fairly light hand … But they weren’t tiger parents at all.”

Their mother, Marnie Fahr Steyer, was a public schoolteacher and a devout Episcopalian. Their father, Roy Steyer, was an “irreligious” Jewish lawyer and World War II Navy lieutenant who went on to become, at 27, one of the only Jewish prosecutors at the postwar Nuremberg trials of Nazi leaders.

“My parents’ house was not particularly religious,” he continued. “They had different religions. My father was brought up Jewish he was quite irreligious … My mother was quite religious.

Steyer went to grammar school at New York City’s prestigious Buckley School, high school at the New Hampshire prep school Phillips Exeter Academy, Yale University and Stanford University’s Graduate School of Business.

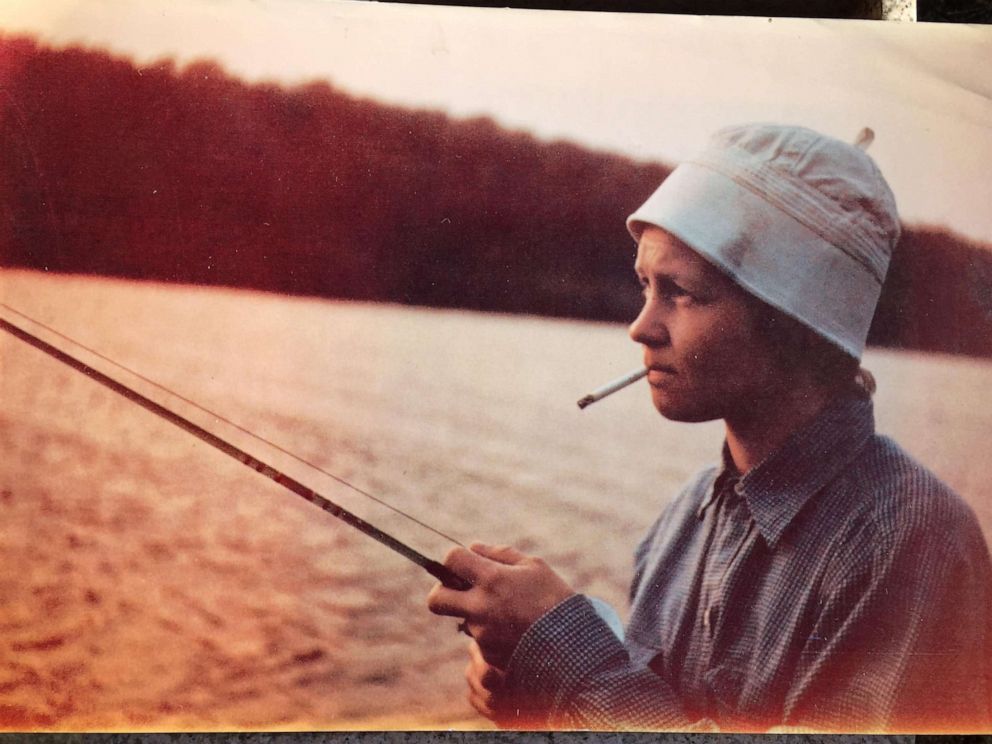

Tom Steyer campaign

Tom Steyer campaign

The candidate himself describes their mother as a “very hard-ass progressive.”

“My grandfather was a professor at the University of Minnesota. My mother left Minnesota and went to Wells College in upstate New York, and the day she graduated she moved to New York City. My grandfather told her, ‘if you move to New York City not only will I not give you a penny’ – not that he was rich – ‘but I’ll never speak to you again.’”

“She moved the next day,” Steyer said.

True to his word, Steyer’s grandfather never spoke to her again.

She became a journalist at Newsweek — part of a class of then-marginalized female reporters who would later become renown for their journalistic prowess — and later wrote and helped produce the NBC Nightly News, Steyer said.

After marrying their father, she went back to school and got a masters’ degree and began teaching English and remedial writing in New York City public schools and, later, at what was then known as the Brooklyn House of Detention, a jail in downtown Brooklyn for inmates awaiting trial.

“She was a contradiction in terms: a devout Episcopalian,” Steyer said with a grin. “She voted for Shirley Chisolm in ’72. She was railing for civil rights and against Vietnam. She was a very hard-ass progressive.”

“She really liked to have fun, really liked to fish, really liked to drink, really liked to smoke cigarettes,” he recalled. “She was the kind of person who would say …. ‘you goddamned son of a bitch!’ But if you said f— or s—, she’d have a heart attack. She loved to hunt she loved to fish, she loved the outdoors as a girl.”

He said his mother was even active outdoors in New York City

“She once caught a fish in the boat pond in Central Park,” he said. “She was practicing her fly-fishing skills and she caught a goldfish!”

Campaign Rituals

Steyer acknowledged that he has a number of personal rituals and reminders he leans on to keep him focused on the work he’s doing.

For years, he’s been drawing what’s known as a Jerusalem Cross on the back of his left hand before attending church, hitting the campaign trail or speaking in public.

“I write a cross on my hand to remind myself to tell the truth, no matter what the cost,” he told ABC News, displaying the pen-inked cross.

He said it’s based on “the idea that if you’re right and you tell the truth, you’re right even if takes 2000 years, even if you have some pain along the way, shall we say.

“It’s to remind myself that there’s a point here, there’s a mission here.”

Chris Francescani/ABC News

Chris Francescani/ABC News

He also has for years worn the same red-patterned Scottish plaid tie design, and is partially to colorfully-beaded belts.

He listens to gospel music to focus him before big rallies, particularly Aretha Franklin’s chart-topping 1972 live album “Amazing Grace,” recorded at the New Temple Mission Baptist Church in Los Angeles, and released this year as a documentary film.

“It’s blow-your-mind good!” he said enthusiastically of the soundtrack, which he said grounds him.

“There’s something to be done here, and you’ve got to get your energy up to do it,” he explained in describing these daily reminders. “You’ve got to get your gumption up, and get yourself ready … People are going to push back. So you’re going to have to go do it. It’s like game day,” said the veteran collegiate athlete. “Bring it on.”

Steyer said that he’s unfazed by criticism that a billionaire who has never held elected office has no place running for the U.S. presidency.

“I don’t think I’m comparable to other billionaires,” he responded sharply. “Where are the other billionaires who spent 10 years building coalitions?” he challenged a reporter.

“You literally can’t name one.”

But Steyer pivots easily back to his light-hearted self in response to a simpler point of contention: which of the three Steyer brothers is the “funny one.”

“Oh my God, I’m way funnier than those losers!” he insisted, making a point that both brothers, in separate interviews, conceded.

‘Don’t sound so smug’

Steyer is an Episcopalian who began seriously studying the Bible as a young teenager.

“I didn’t think there was just one way to go,” he said. “So I went and read the Bible. I’d say I read it somewhat growing up and, I would say, really started thinking about around 13. And I called my mom and said, ‘Mom, I believe in God!’

“And she said, ‘Sonny, don’t sound so smug. There are many people out there smarter than you that already believed in God,’” he recalled.

Steyer said faith brings meaning to his life, and that he believes faith can’t take different forms for different people. Ultimately, he describes it as a “positive life force.”

“Look you’ve got to be part of the positive life force,” he said. “You’ve got to find your way to the positive life force. I mean someone in my background can’t believe there’s only one way. And I don’t. And you have to find it. But you choose it. I have a friend who says “GOD: Great OutDoors.” Fine. If you can do it, fine. Any way you can do it – fine — but if you don’t do it,” he said of finding meaning and purpose in faith, “than I really think that you know at some level you’re really missing the point.”

“Honestly?” he continued. “If you’re not doing that, I don’t know exactly what it is you are doing on this Earth.”

Dan Morian, a veteran California statehouse reporter who now works for the non-profit political reporting website CalMatters, said that Steyer’s engaging authenticity and boyish enthusiasm could surprise people.

“Not that I’ve met a lot, but of the billionaires I’ve known, he’s the most normal,” Morian said. “He feels to his core that God gave him this life for a reason … He’s one of the few people you meet that that’s got a genius level IQ … just really, really smart and kinda crazy. And not like Trump crazy, like he’s gonna start a war.”

‘Kat’

Tom Steyer campaign

Tom Steyer campaign

Steyer met his wife, Katherine Taylor — known to those close to her as “Kat” — at Stanford University and the couple married in 1986.

Friends and family told ABC News that Taylor has had a profound effect on her husband’s public initiatives. The couple were among the first to sign Bill Gates and Warren Buffett’s Giving Pledge in 2010 – a promise to give away a majority of their fortune.

In 2006, the couple founded a company that delivers broadband connectivity and teaches computer literacy to small towns in rural Mexico and India. The following year, they founded Beneficial State Bank, which provides commercial banking services to underserved small businesses and non-profits in the Bay Area.

“Kat is like Tom in certain respects,” said Hume Steyer, “in that she really, really, really wants to do the right thing … And she’s very, very sincere, just like Tom.”

Yet “Tom and Kat have different reactions to Tom’s acquisition of wealth. Tom is very, very happy to take all of his wealth and put it to good use. I mean this – he doesn’t care about personal comfort at all. If it wasn’t for Kat, he’d still be sleeping on a futon.”

“But he’s not guilty about having made all this money. He doesn’t regret it on any level at all. And he doesn’t perceive the slightest fault in that he made it, or how he made it. Kat … does not feel the same way.”

Taylor did not respond to a request for comment for this story.

Chris Francescani/ABC News

Chris Francescani/ABC News

Hiking with billionaires

By 2012, Steyer was squarely focused on the environment. He retired from Farallon and contacted environmentalist Bill McKibben — after reading an influential article on climate change that McKibben wrote that year for Rolling Stone magazine. But McKibben wasn’t very interested in a meeting — so he took the billionaire hiking.

“He called up and wanted to meet and talk about that [Rolling Stone] piece and truthfully – since I didn’t know him from Adam and since my general desire to meet with hedge fund people is pretty small, I demurred at first,” McKibben told ABC News. “But it came out that he knew this part of the world where I live and had connections to the Adirondacks, the great mountains up here, so I finally decided, ‘what the hell.’ We’d go for a hike, and you know, if he was a rich, boring guy at least we’d be hiking and not waste the day. It turned out he was a completely fascinating guy – a fascinating and good-hearted human being.”

“He’s a good hiker and that counts a lot in my book,” McKibben continued. “We went quickly up the mountain — called Giant Mountain — in the Adirondacks. We were talking all the way. I was fascinated by what he’d done in the world, his ability to analyze things quickly — which I guess is what investors do — and he was highly-interested in … I know a lot about climate science and climate politics and he was just deeply, deeply, deeply interested in that, so we just talked from the bottom of the mountain to the summit and then back down again, and we’ve kept up the conversation regularly [ever] since.”

McKibben said he’s heard Steyer described as a liberal version of the Koch brothers — the billionaire conservative mega-donors Charles and David Koch, whose political contributions have injected hundreds of million into mostly conservative and libertarian causes that often coincided with their business interests. But he said he flatly disagrees.

“No,” McKibben said, “I don’t think that’s actually accurate.”

“The Koch brothers act out of self-interest. All their political spending and things is designed to advance the interest of their oil and gas business and Steyer’s I think quite generally acting in the public interest. He’s out there advocating for policies that would make life tougher for rich people not easier. I think he’s the anti-Koch brothers.”

ABC News’ Meg Cunningham, Felisa Fine and Brad Martin contributed research to this report.

[ad_2]

Source link