Adventures with Van Gogh is a weekly blog by Martin Bailey, our long-standing correspondent and expert on the artist. Published every Friday, his stories range from newsy items about this most intriguing artist to scholarly pieces based on his own meticulous investigations and discoveries. © Martin Bailey

A new theory suggests that Van Gogh may have shot himself in the fields just above the inn where he was lodging, not further away. The traditional view is that the artist pulled the trigger in a wheatfield behind the Château de Léry, which is nearly a kilometre away.

After the shot missed his heart, but left him severely wounded, he staggered back to his room in great pain. This was in the evening of 27 July 1890, in the village of Auvers-sur-Oise (outside Paris), and he died two days later from the injury.

Immediately after Van Gogh’s death there were reports that the shooting had taken place “behind the chateau”, but specialist Wouter van der Veen’s fresh hypothesis came when he asked a simple, but apposite (and previously unasked) question: which château was it?

Paul Gachet (pseudonym Louis van Ryssel), The Place where Vincent committed Suicide (1904) Credit: Musée Camille Pissarro, Pontoise

What was traditionally thought to be the spot behind the Château de Léry was recorded in 1904 in a painting by Paul Gachet Jr, the son of Dr Paul Gachet, the friend who treated Van Gogh. On the reverse it is inscribed: “De l'endroit où Vincent s'est suicidé” (Of the place where Vincent committed suicide).

The site in the Gachet Jr painting has been identified by other experts because of the gateway in the ancient stone wall on the north of the château woods. This narrow lane is known as the Chemin des Berthelees. Where a farm once stood, there is now a carpark by a 1990s housing estate.

Wall in Chemin des Berthelees, Auvers-sur-Oise

Credit: Martin Bailey

The picture was painted while his father was still alive, so it presumably reflects Dr Gachet’s knowledge. This location has long been accepted, since the doctor (along with Vincent’s brother Theo) would have been in the best position to have heard about the place from the wounded artist. There seems little reason for the Gachets to have invented the location.

To add to the evidence, a late 19th-century gun was discovered buried in the earth. The gun had been ploughed up in around 1960 by a farmer who owned this field and other land. This discovery was only publicised in 2019, when it was auctioned in Paris, fetching €162,500.

The Lefaucheux revolver, probably the one used by Van Gogh and said to have been found in a field behind the Château de Léry Credit: © Martin Bailey

The location depicted by Gachet Jr is consistent with what was written by fellow artist Emile Bernard, who attended Van Gogh’s funeral. Two days afterwards Bernard wrote that his friend had gone “behind the château”, near a wheatstack. This was also backed up by a local newspaper, Le Régional (7 August 1890), which reported that just before the shooting Van Gogh had set off “towards the château”.

The massive Château de Léry (which by chance is now a visitor attraction with an audio-visual presentation on Van Gogh) dominates the Oise valley and is usually simply called the “Château d’Auvers”.

The Léry chateau location may seem convincing, but Van der Veen has researched the question, using a range of sources, and is questioning accepted wisdom, putting forward what he describes as a new hypothesis. He asks: could it be another château?

He points out that in the late 19th century there was another building in Auvers which was also referred to as a “château” (castle or rural mansion house), although from the mid-20th century it was more normally called a “manoir” (manor). This more modest building is now known as the Manoir des Colombières (it currently houses the Musée Daubigny, a museum named after the artist Charles-François Daubigny).

Manoir des Colombières (Musée Daubigny), Auvers-sur-Oise

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Van der Veen cites an 1899 study by the local schoolmaster Samson Cazier and a 1901 book by the historian Henri Mataigne, which both refer to it as the “Château des Colombières”.

Henri Mataigne’s drawing Porte du Château des Colombières (Gate of the Château of Colombières) in his Monographie Communale (1899)

Credit: Archives départementales du Val d’Oise, Pontoise

The Colombières mansion lies only one minute’s walk from Van Gogh’s inn and the wheatfields above it are only a further five minutes away. One can only speculate whether Van Gogh would have preferred to shoot himself fairly close to the inn or at some distance. However, if it was close by, then this does help to explain why he was more easily able to stagger back to his room.

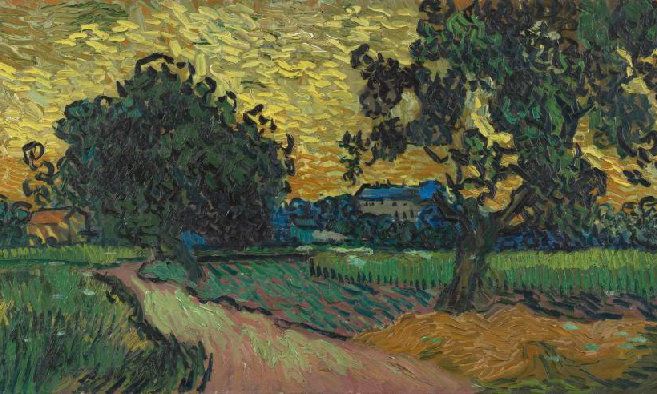

But one of the problems with Van der Veen’s hypothesis is is that Van Gogh himself thought of the “château” as the Léry building, which he depicted in one of his most atmospheric Auvers landscapes. Writing to Theo, he described the twilight picture as “two completely dark pear trees against yellowing sky with wheatfields, and in the violet background le château encased in the dark greenery”.

Van Gogh’s Landscape at Twilight (June 1890), depicting the Château de Léry

Credit: Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

The “château” issue remains unresolved. My initial feeling is that it is more likely that Van Gogh shot himself behind the Château de Léry, as traditionally assumed, but it is an interesting idea that it could have been in the wheatfields above the Manoir des Colombières. If this new hypothesis is correct, the suicide spot would have been close to where he painted Tree Roots (July 1890), his final painting. Van der Veen believes it likely that Van Gogh “went straight to the nearest wheatfield, crossing the roots he had just immortalised, to confront, one last time, the sun amid the harvest”.

Martin Bailey is the author of Van Gogh’s Finale: Auvers and the Artist’s Rise to Fame (Frances Lincoln, 2021, available in the UK and US ). He is a leading Van Gogh specialist and investigative reporter for The Art Newspaper. Bailey has curated Van Gogh exhibitions at the Barbican Art Gallery and Compton Verney/National Gallery of Scotland. He was a co-curator of Tate Britain’s The EY Exhibition: Van Gogh and Britain (27 March-11 August 2019).

Martin Bailey’s recent Van Gogh books

Bailey has written a number of other bestselling books, including The Sunflowers Are Mine: The Story of Van Gogh's Masterpiece (Frances Lincoln 2013, available in the UK and US), Studio of the South: Van Gogh in Provence(Frances Lincoln 2016, available in the UK and US), Starry Night: Van Gogh at the Asylum (White Lion Publishing 2018, available in the UK and US) and Van Gogh’s Finale: Auvers and the Artist’s Rise to Fame (Frances Lincoln 2021, available in the UK and US). Bailey's Living with Vincent van Gogh: the Homes and Landscapes that Shaped the Artist (White Lion Publishing 2019, available in the UK and US) provides an overview of the artist’s life. The Illustrated Provence Letters of Van Gogh has been reissued (Batsford 2021, available in the UK and US).

To contact Martin Bailey, please email [email protected]. Please note that he does not undertake authentications.

Read more from Martin's Adventures with Van Gogh blog here.