[ad_1]

The Sackler family has been behind many art world projects of the past few decades, from the beautiful new courtyard of London’s Victoria and Albert Museum to modest but intellectually vital activities such as the Research Forum at the Courtauld Institute. However, due to their pharmaceutical business and its role in the opioid crisis in the U.S., activists have been calling out the museums, asking them not to accept any more money from the family.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York is the latest institution to cut connections with the Sacklers. The museum, which has an entire gallery which bears the family’s name – an honor reserved only for the most generous of donors, has been under public pressure for months, serving as the site of several notable protests related to anti-Sackler activism since last March. The announcement came the same day that the American Museum of Natural History in New York said it had made a similar decision, without giving details. Daniel H. Weiss, The Met’s president and CEO, said in a statement:

Every object and much of the building itself came from individuals driven by a love for art and the spirit of philanthropy. For this reason, it is our responsibility to ensure that the public is aware of the diligence that we take to generate philanthropic support. Our donors deserve this, and the public should expect it.

What is the connection between the opioid crisis and the Sackler’s family art philanthropy?

The Sackler Family and the Art Philanthropy

The Sackler name is emblazoned on dozens of the world’s greatest museums, universities, and performing arts centers. Making their name as philanthropists, they supported major institutions such as The American Museum of National History, Guggenheim, The Smithsonian, Tate Gallery, The Louvre, universities like Harvard, Oxford, and Cambridge, among others, many of which today have wings named after the family. They also endowed numerous professorships and underwritten medical research.

Richard, the son of the late Raymond Sackler, once said: “My father raised Jon and me to believe that philanthropy is an important part of how we should fill our lives.” However, the Sacklers’ altruism appears to be connected to a compelling narcissistic ambition of attaching their name to humankind’s greatest achievements.

The OxyContin and Addiction

In 2015, the family was listed in Forbes’ list of America’s Richest Families, with a collective net worth of $13 billion. Sons of Isaac Sackler and his wife Sophie, Arthur, Mortimer and Raymond Sackler, bought a small pharmaceutical company, Purdue Fredericks, in 1952. Now known as Purdue Pharma, the company introduced OxyContin in 1996, misbranded and heavily promoted drug regarded as the main factor in the opioid epidemic. As the Sacklers saw increased scrutiny in the late 2010s over their association with OxyContin, David Crow, writing in the Financial Times, described the family name as “tainted”.

A controversial drug, OxyContin contains oxycodone as its sole active ingredient, a chemical cousin of heroin which was previously rarely prescribed by doctors for its addictive properties except for acute cancer pain and end-of-life palliative care. The family misinformed the medical community through funded research which dismissed the concerns about opioid addiction as overblown, pushing doctors to change their prescribing habits.

The entire marketing of the drug was based on convincing doctors of the drug’s safety with literature that had been produced by doctors who were paid by the company. For instance, the highly regarded doctor Russell Portenoy, who received funding from Purdue, spoke out about the problem of untreated chronic pain saying that opioids needed to be destigmatized, amounting concerns about their addiction and abuse to a “medical myth.”

As Barry Meier writes in Pain Killer, “In terms of narcotic firepower, OxyContin was a nuclear weapon.” While many patients found the drug to be a vital salve for excruciating pain, many more others developed severe addiction. Purdue marketed it as a drug with a twelve-hour relief, which was not the case with the majority of patients who required more medication before this time mark. This was a recipe for withdrawal symptoms between doses, leading to addiction and abuse. However, the company insisted that it was a matter of individual responsibility as people were not taking OxyContin as directed, while the dangers of the drug were actually intrinsic to it.

The Centers for Disease Control blamed opioids for two-thirds of the 70,000 overdose deaths in the US in 2017, adding that 1.7 million people were suffering from addiction to painkillers like OxyContin in the same year. At the same time, it has been stated by the American Society of Addiction Medicine that four out of five people who try heroin today started with prescription painkillers.

Domenic Esposito – The Opioid Spoon Project

The Activism Against the Sackler Family

In 2002, Marianne Skolek Perez, mother of the twenty-nine-year-old Jill Skolek from New Jersey who died in her sleep from respiratory arrest caused by OxyContin, wrote to F.D.A. officials urging them to append to OxyContin packaging a warning about the risk of addiction. The following year, a New York trial lawyer Paul Hanly assembled a lawsuit, signing up five thousand patients who said that they’d become addicted to OxyContin after receiving a doctor’s prescription. He brought together documents which showed that the supposed safety of the drug was emanated from the marketing department, not the scientific one. The lawsuit ended with a seventy-five million dollar settlement. Soon after, other lawsuits followed.

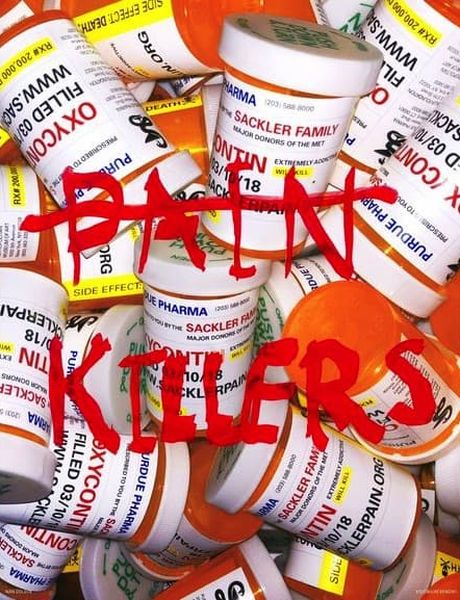

In January 2018, the artist Nan Goldin, who revealed her struggles with opioid addiction, formed an activist group PAIN (Prescription Addiction Intervention Now) and launched an online petition calling for the Sackler family and Purdue Pharma to take responsibility for the opioid crisis in the US. It demanded that the Sacklers immediately pay for rehab treatment, opioid addiction education and the installation of “public dispensers of Narcan, the medicine that reverses an overdose, on every corner in America”. The group stated they intend “to put pressure on museums, art spaces and educational institutions to refuse future donations from the Sacklers” and “put social and political pressure on [the family] to respond meaningfully to this crisis”.

In March of the same year, the group staged their first protest at the Metropolitan Museum’s Sackler Wing, tossing prescription pill bottles labeled OxyContin into the moat surrounding the Temple of Dendur and unfurling banners that read “Shame on Sackler” and “Fund Rehab”. The group also handed out pamphlets with facts about the US opioid crisis and demands for Purdue Pharma and the Sackler family, including funding for treatment and addiction education. In the following months, the group held several protests at New York museums such as The Met and Guggenheim.

In April 2019, the German artist Hito Steyerl denounced Sackler sponsorship of cultural institutions at the preview of her exhibition at the Serpentine Sackler Gallery. During the opening, Steyerl said that the art world must work together to tackle the issue of Sackler sponsorship because no institution or artist can act alone. The show included an augmented reality app through which visitors can see a version of the building’s façade where the Sackler name is notably absent.

The Museums Respond

The past year has seen a growing backlash to Sackler philanthropy from museums in the UK and internationally, raising interesting questions about sponsorships and donations museums accept.

In March 2019, the National Portrait Gallery (NPG) in London and the Sackler Trust announced that they would not proceed with the trust’s £1m donation towards the gallery’s building development. Previously, Goldin had said she would withdraw from a planned retrospective at the museum if it accepted the gift.

In the following weeks, the Tate, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York and the Jewish Museum in Berlin have declared that they would not accept future donations from the Sackler family. Meanwhile, the South London Gallery quietly returned a £125,000 grant from the Mortimer and Theresa Sackler Foundation last year.

After announcing they would re-assess its gift acceptance policy earlier this year, the Metropolitan Museum of Art announced they would not be accepting gifts by the Sackler family. As Daniel Weiss explained, “we all have become increasingly focused around issues of accountability,” noting that the controversy over the Sacklers involved “a very serious public health crisis with pending litigation”.

It appears that museums started to realize that they should be more discerning about donors as they might be putting future fundraising at risk by keeping tainted money and thereby becoming identified in the public imagination as fronts for laundering reputations. However, the issue of ethical philanthropy goes far beyond the Sacklers and some crucial general questions about regulating the field should be addressed as soon as possible.

Featured image: American Wing, the Met Museum, image via Wikimedia Commons.

[ad_2]

Source link