[ad_1]

The Los Angeles County Museum of Art, also known as the LACMA is a respectable institution that hosts grand, yet conceptually rounded exhibitions reflecting both the urge to reanalyze historical artistic oeuvres and the contemporary ones.

In the upcoming period, the museum will present three outstanding exhibitions focused on the domains of Frank Stella, Eleanor Antin, and Isaac Julien. Although their practices differ in approaches, what they seem to share is a continuity in practice and a strong sense for radicalism; along with these two common characteristics, Antin and Julien also share an impeccable socio-political engagement.

Frank Stella: Selections from the Permanent Collection will be open at the LACMA from 5 May to 2 September 2019; Isaac Julien: Playtime will be on display from 5 May until 11 August 2019, while Eleanor Antin: Time’s Arrow will open on 12 May and the audience will be able to see it until 7 July 2019.

To bring you closer to each exhibition, we asked their curators to reveal details regarding their process and explain the importance of these incredible artists.

Eleanor Antin: Time’s Arrow

The 1960s nurtured a new generation of artists willing to break all art conventions from every possible perspective. In particular, it was women artists who came to prominence by introducing a well-articulated critique of patriarchal modes; the movement grew and spanned across the US and even further, and one of the pioneers was Eleanor Antin; her entire multimedia oeuvre is embedded in performativity, and she is best known for her iconic works such as 100 Boots (1971–73) and Carving: A Traditional Sculpture (1972).

LACMA’s decision to present Antin’s work is undoubtedly based on the bare fact that this prolific artist never stopped radically exploring new modes or representation within her own work. The upcoming exhibition Eleanor Antin: Time’s Arrow will feature four crucial artworks – the mentioned Carving: A Traditional Sculpture (photographs depicting transformation of the artists’ body) and its reenactment Carving: 45 Years Later, as well a new self-portrait, !!! (2017), and a related serial work, The Eight Temptations (1972).

The exhibition is curated by Michael Govan, LACMA CEO and Wallis Annenberg Director, together with Dhyandra Lawson, curatorial assistant in the Wallis Annenberg Photography Department at LACMA, who was kind enough to provide us with certain details regarding the production of Eleanor Antin: Time’s Arrow.

Widewalls: Eleanor Antin is definitely one of the leading pioneering feminist artists and her works question how the patriarchy defines the female experience, body and the self. Why is it important for young people to understand the domains of Antin’s practice and the politics behind it, especially in regards to the current American socio-political context?

Dhyandra Lawson: Throughout her fifty-year artistic career, Eleanor Antin has investigated the nature of “the self.” In seminal works where she took-on different identities and performed them in the world, such as The King of Solana Beach (1974-75), and in her pseudo-scientific, photographic documentation of her own weight loss in CARVING: A Traditional Sculpture (1972), Antin resisted rigid notions of identity, and engaged ideas about what constitutes the self.

She notably stated in 1974:

I am interested in defining the limits of myself…The usual aids to self-definition—sex, age, talent, time and space—are merely tyrannical limitations upon my freedom of choice.

Antin’s CARVING from 1972 and her recent, monumental re-staging of the piece, CARVING: 45 Years Later (2017), presented together for the first time in Time’s Arrow, provoke reflection on how the self transforms over time. In each work, Antin enacts, in her view, the method of a classical Greek sculptor, manipulating her body through weight loss, as a sculptor would remove layers of stone to reveal some “idyllic” form latent in the material.

In this way, Antin’s work suggests the self is constantly unfolding. She creates the opportunity for viewers to examine and re-define social constructs, such as beauty, for themselves. I find the artist’s practice to be incredibly empowering, and important for a younger generation of viewers to critically consider how identity is constructed.

Widewalls: Can you describe your working process with the artist?

DL: I have had a great honor and enormous pleasure of collaborating with Eleanor Antin on every aspect of the planning of Time’s Arrow. LACMA is pleased to present Antin’s third monograph at the museum, opening on May 12, where it will also travel to the Art Institute of Chicago, August 17, 2019 — January 5, 2020.

Widewalls: Is there any specific work which you find equally powerful in the contemporary moment?

DL: Antin is a pioneer and I see the influence of her practice ripple in an emergent generation of artists, both directly and indirectly. CARVING: 45 Years Later is a landmark work of Antin’s recent career, and we are thrilled to debut it at LACMA.

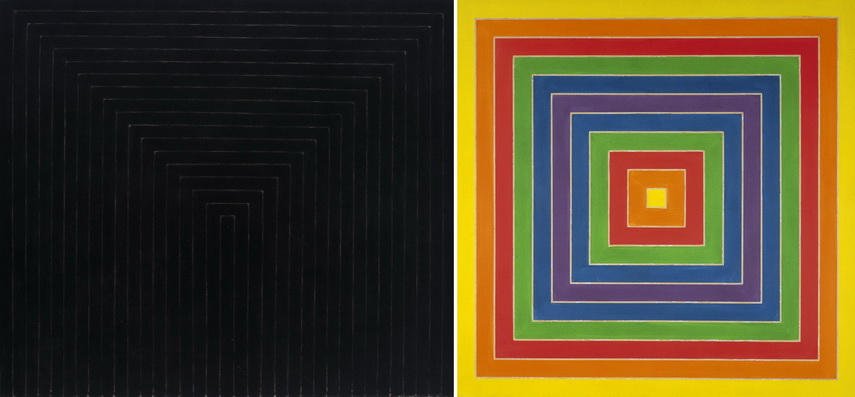

Frank Stella: Selections from the Permanent Collection

The second exhibition about to open in LACMA is a retrospective of the great American master Frank Stella. The installment will be conducted of the works form the museum’s permanent collection and will be presented in loose chronological order; some of the works have not been seen in public for more than three decades.

By encompassing an array of works made throughout his career, from the 1950s iconic Black Paintings to his late monumental sculpture, this show will definitely present a fine insight into Stella’s grandiose oeuvre.

The LACMA curator Katia Zavitovski shared with us her impressions regarding the exhibition-making process.

Widewalls: LACMA owns a great number of Frank Stella’s works; however, some of them were not publicly displayed for more than thirty years. Could you tell us a bit more as to why that is so?

Katia Zavitovski: As with most museum collections of modern and contemporary art, unfortunately only a fraction of LACMA’s holdings are on view at any one time.

However, Stella’s iconic black painting, Getty Tomb (1959), is always exhibited in our permanent collection galleries, and we have made other Stella works available for loan – for instance, both Inaccessible Island Rail (1976) and St. Michael’s Counterguard (1984) were featured in the 2015 traveling retrospective of the artist’s work. We are thrilled to now be able to show the larger scope of Stella’s paintings and sculptures from LACMA’s holdings.

Widewalls: The artistic practice of this great artist was quite radical. Although he departed from Abstract Expressionism and practically set the foundation of Minimalism, Stella made great efforts to rethink the media, the approach, as well as conceptual and stylistic issues which makes his practice hard to categorize from a contemporary perspective. Would you agree with my impression that in America, his role of an exceptional innovator is perhaps equal to the one of Malevich in Russia?

KS: I think your comparison to Malevich is apt, as a driving force for both artists was/is a passionate exploration of abstraction and pictorial space. Malevich has in fact been an influential figure throughout Stella’s long career – Stella’s early series Irregular Polygons (1965-66) were inspired by Malevich’s Suprematist Composition (with blue triangle and black rectangle) (1915), and over forty years later Stella referred to the early 20th-century pioneer in Circus of Pure Feeling for Malevich (2009).

Widewalls: Aside from the inevitable historical context, in your opinion what are the best interpretational tools for bringing the work of Frank Stella closer to the contemporary audience, especially the youngsters?

KS: Stella’s artistic practice is marked by his continual experimentation not only with color, form, and the general vocabulary of abstraction but also with new materials and techniques. For example, in the 1990s he began using computer imaging technologies, and since the mid-2000s he has employed 3-D printing to make his work. I think this kind of ongoing interest in the cutting-edge connects Stella to young audiences.

Isaac Julien: Playtime

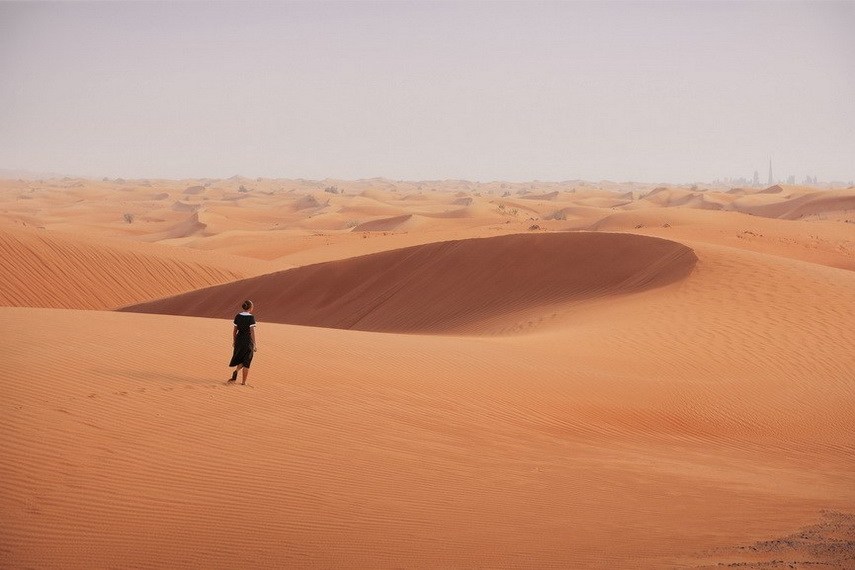

The third exhibition will feature the immersive installation Playtime by renowned British artist Isaac Julien, whose practice manifests mostly through the motion pictures. Since the 1980s and the engagement with the Sankofa Film and Video Collective, Julien has been focused on exploring the visibility of black culture in the local context. Throughout the years, his engaged strategy sprawled to other subjects related to the topics of migration, race, class, and gender. Recently, the artist was more focused on the devastating effects of capitalism.

Playtime (2013) is the best example from his recent production; it is based on Jacques Tati’s 1967 French New Wave film of the same name. Its narrative narrative takes place in three metropoles, London, Reykjavik, and Dubai, covering the transformation of those after the 2008 global financial crisis through the lives of six archetypal characters – the Hedge Fund Manager, the Artist, the Art Dealer, the Auctioneer, the Reporter, and the House Worker.

This peculiar saga about the influence of capital on the art market was shown in various institutions around the world, and this will be Julien’s first solo presentation at LACMA. The exhibition is curated by Christine Y. Kim, associate curator of contemporary art at LACMA, to whom we also talked regarding this exciting exhibition.

Widewalls: The 2008 global financial crisis caused massive changes throughout the global landscape characterized by the increment of social injustice, housing issues and, in general, deepening of the class gap. Although the work of Isaac Julien was made eleven years ago, it seems that these topics are still relevant, if not more, meaning that his work nicely dissects the capitalist matrix. How does the audience connect to it?

Christine Y. Kim: Yes, the global financial crisis of 2008 was part of the initial impetus and narrative for this work. Since then, many of the issues of social injustice, housing issues, and class, race and culture divides have widened, or at least come into sharper focus with the expansion of social media and digital technology and highlighted in the era of Brexit and Trump.

This is part of my impulse and purpose of exhibiting this reflective, prescient and almost premonitory work Playtime from LACMA’s collection. Viewers connect to the film viscerally, as an immersive installation and cinematic masterpiece; intellectually and politically as it reflects on capitalism and power; and personally and emotionally through its narratives on labor and migration, grief and alienation.

Widewalls: The primer reference and the starting point for Julien’s film Playtime is the 1967 French New wave film made by a cinematographer Jacques Tati, a dystopian comedy exploring the prevailing influence of the raising capital and commodification of place, goods, and people. However, the artist’s film takes a slightly different narrative. Could you emphasize a bit on Julien’s process?

CYK: Julien is an expert at infusing provocative and even subversive commentary through his implication of film and art history. Whether taking up the legacies of Marx in Kapital, blaxploitation in Badasssss Cinema, or Chinese film, landscape and mythology in Ten Thousand Waves, his narratives are rich with research and references yet unique in his own trajectory and complication of those narratives, structures, characters, histories and visuals.

Widewalls: Is it possible to conclude, on the account of Julien’s film, that history is repeating and that our existence is indeed formatted by the continuum of capitalism?

CYK: I can’t speak for the artist, but as a curator, yes, repeated narratives of colonialism and capitalism continue through the 21st century. Playtime was conceived as one of a trinity of films with Ten Thousand Waves and Kapital, all of which, together, address facets and extensions of our colonial past and capitalist economy and society.

Featured images: Isaac Julien – Eclipse (Playtime), 2013, © Isaac Julien, photo courtesy the artist, Victoria Miro Gallery, London and Metro Pictures, New York; Frank Stella – Bampur, 1966, acrylic and day-glo on canvas, 108.5/16 x 83 in., Los Angeles County Museum of Art, gift of the Phil Gersh Agency, Inc. through the Contemporary Art Council, © 2019 Frank Stella/Artists Rights Society (ARS) New York, photo © Museum Associates/LACMA; Isaac Julien – The Abyss (Playtime), 2013, © Isaac Julien, photo courtesy the artist, Victoria Miro Gallery, London and Metro Pictures, New York. All images courtesy LACMA.

[ad_2]

Source link