[ad_1]

On Wednesday, I was on no fewer than three group texts between white women asking what they could do about white women.

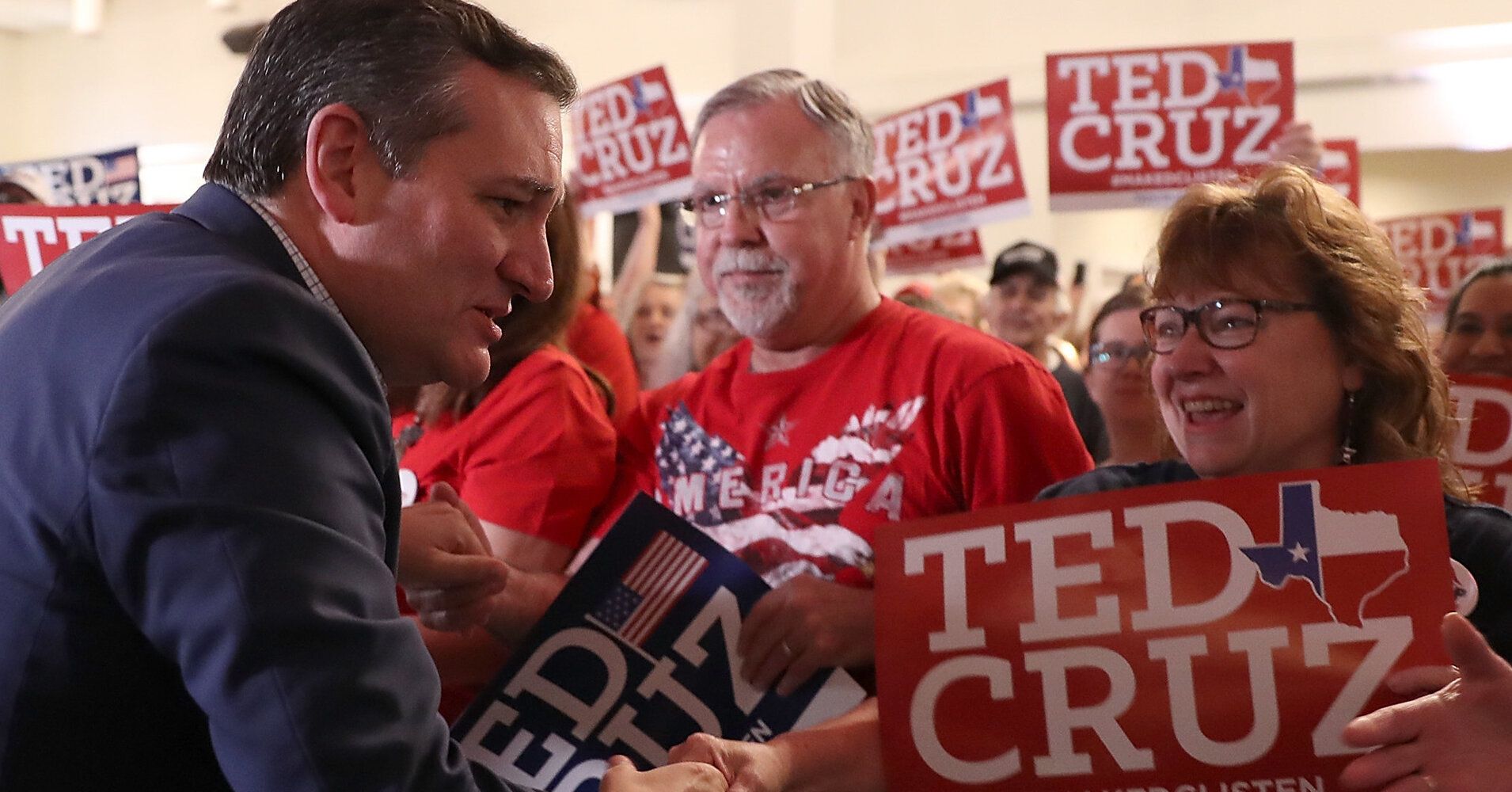

It was the day after the midterm elections, and the exit poll numbers showed, once again, that more than half of white women voters voted Republican in key races in Florida and Texas, and that more than three-quarters of white women voters had voted against gubernatorial candidate Stacey Abrams in Georgia.

Despite the historic gains made by women this week ― Americans will be sending more than 100 women to Congress, many of them young women of color ― a familiar fact reasserted itself. As Elie Mystal put it on Twitter: “White women gonna white.”

My texting friends wanted to understand what they could do to call their fellow white women in, to check them on their alliance with the forces of white (and male) supremacy. I saw a slew of posts on Instagram from progressive women calling on white women to do better, to come for each other, to step up and take responsibility for their sisters.

It makes sense to group white women together and look at their voting patterns. Those patterns are real and have a real effect on elections. They also tell white people something that people of color have always known: White women prop up and benefit from white supremacy just as white men do. They (we) are and have historically been, as Rebecca Traister wrote, some of “white patriarchy’s most eager foot soldiers.” And even within so-called liberal enclaves, racism remains a powerful force, one that “nice white ladies” abet if they’re not actively challenging it.

But on a practical level, broad calls for white women to come for white women can flatten the reality of just how divided white women are from each other. Yes, white women as a whole tend to vote Republican, but dig into the data and deep schisms based on religion, region, marital status, education and age become apparent. For example, white women as an aggregate voted Republican and have for years, but college-educated white women did not.

So, where do we ― “we” being white women who want to do effective, anti-racist political work ― go from here? I reached out to Corinne McConnaughy, a political science professor at George Washington University and author, whose work focuses on the roles gender and race play in shaping American politics and institutions. She was blunt with me in stating that women as a whole and white women specifically are not cohesive political blocs, and likely will never be. She also encouraged white women on the left to focus their energies where they are most useful: mobilizing within their subgroups and calling in the sympathetic but less than active white men in their lives. Below is our conversation, lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

In your work, you talk a lot about the way that women are not actually a unified political bloc. I’m wondering how we saw that thesis play out during the midterm elections?

I think the thing that’s going to be hard for people to hold together is that we can have a significant gender gap [in voting for Republicans versus Democrats], and we can have these new historic wins for women candidates and at the same time the overarching story can be that most women are voting [based on factors] other than, “I have a common interest with other women.”

The key is understanding that the [gender] gap, though it’s statistically large enough to swing some elections, is still pretty small. We’re talking about a couple of percentage points of difference between aggregated men’s voting behavior and aggregated women’s voting behavior.

But that’s the key. It’s not that 80 percent of women behave a certain way. They don’t. It’s that a subset of women have had a gendered reason to make a particular voting decision, and they’re rightly positioned to swing some elections and create an aggregate noticeable gap. So instead of thinking, “What do women voters do?” think instead, “Which women made different decisions than their male counterparts?”

Are there any groups of women we saw break from their male counterparts this week?

College-educated white women, particularly in the suburbs, are making noticeably different decisions than their male counterparts [and voting more Democratic]. Black women are the most Democratic voting group. They are different than their black male counterparts, who are more likely than black women to vote Republican. But there’s no reason to think, and there’s no evidence to suggest, that those black women and those white, college-educated, suburban women are behaving differently than their male counterparts for the same reason. Black women are the glue holding together the black community. The civil rights movement was built on their backs, so I think that’s a long-standing pattern, and that’s different than the reason that the educated, white women in the suburbs are suddenly voting more for Democrats.

The key is that where white women have been able to hold other white women accountable has been inside of some other grouping where their commonality is defined not just by being white women.

Corinne McConnaughy, political science professor at George Washington University

So is it just not useful for us to speak about women as a political group at all?

That’s the hill I’m going to die on. We don’t talk about men as a [cohesive political] group. We do with men voters what we should be doing with women voters, which is we talk about specific segments of the electorate that are male that are doing a particular political thing because of the way that gender incentive is working out in that particular space. We should talk about kinds of women voters, and we should talk about when we think gender is providing a reason for behavior that is splitting voters who should for other reasons be behaving the same way.

When politicians invoke women as a monolith, what are they trying to do?

It’s this really handy tool in doing politics that everybody gets to say “women,” right? What happens is that if they’ve got the message right, then a set of women hear it as, “Oh, this is about me.”

Womanhood and manhood are such intimately derived identities that we use these big categorical terms. All of us do it, when we know full well we don’t mean all of the group, but we do it because using that big categorical term and then filling in the content that we claim goes with it is resonant among the subset [we’re a part of]. This is the “Oh, gosh, of course women are concerned about unequal pay in the workplace.” Well, no, not all of them are, actually, but the ones who are hear their interests as definitional of the category. That’s empowering. “Ah, yeah, that’s what it means to be a woman.”

This goes all the way back, like the Declaration of Sentiments, which is [considered a] foundational document for the suffrage movement. My students are required to read it very carefully every semester because it’s supposed to be this document documenting the horrible things that men have done to women, the same way the Declaration of Independence [recorded] what the king did to the Colonists. Well, you read it and it’s a bunch of privileged white women’s concerns.

So, I’d assume that invoking “women” as one group can also be an effective organizing tool.

It can be useful to use the term. But know using the term is about mobilizing a specific segment [of women]. And don’t expect that what you’re up to is going to create some sort of bloc of women in politics. We are half the population. We are not all anywhere near socially interconnected. Which is usually different from racial and ethnic minority groups. It makes a lot of sense to talk about black voters and to talk about making appeals to black voters as a group because there’s enough social interdependence defined by blackness. Women aren’t a social group.

Would you consider white women to be a cohesive social group?

No. I am always looking for spaces that are social groups where there is potential for women and men in those spaces to be diverging in exactly how they are navigating that other identity. Like white evangelicals, that’s a [social] group. They are tied together by a religious structure. There [are] leaders, there’s a real sense that this is a community. Women aren’t a community. So you might look at white evangelicals and say, gosh, what happens if women start to define the experience of being a white evangelical differently? There are some young evangelical women pushing hard to try to make that happen.

One of the reasons I’m really interested in talking to you about white womanhood is because on the left, especially since 2016 when exit poll data showed that 52 percent of white women voters voted for Donald Trump, there have been increasingly loud calls for white women to come for our own.

Well, I guess that’s a question I have for you.

What are the social mechanisms? Like, what are the levers [for white women] to pull over each other? Part of the uniqueness of black women’s lived experience [in this country] is that there is truly a social interdependence, black people letting each other know, like, “I have my eyes on you, and it matters that you make the right choice ― the choice that is the anti-white supremacy choice.” That that has weight. But what’s my lever over other white women? What’s tying us all together? How am I able to sanction them? There isn’t a sense of common stakes [between white women as a whole group]. And I think part of the thing is, there’s a continuum here, of how much group-ness there is. I think it’s more likely that we can see episodic changes in behavior.

My work on the suffrage movement was looking at how [it gained] enough leverage to do the costly politics that it takes. It involved women who were organized inside their social groupings. For example, women in labor unions. Members of labor unions are beholden to each other in really important ways. They have a common leadership, they have a sanctioning structure. So I think that’s where we look for what leverage we can have. I think if we are learning anything from the Trump era, it’s that people have to care about the sanctions for violating the norms. And if they don’t care about the sanctions or the norms, then it doesn’t matter that you’re trying to point out that they didn’t adhere to the norm.

We keep asking white women to get other white women. Why are we not asking white women who are sympathetic to the left to come for those marginally sympathetic, tied-to-them-socially white men?

Corinne McConnaughy

From an activist and political organizing perspective, is the answer just to throw your hands in the air and say white women can’t come for other white women?

I think the key is that where white women have been able to hold other white women accountable has been inside of some other grouping where their commonality is defined not just by being white women. Teachers’ unions are a good example. Women can say, “Look, here’s our common interest,” and use that space where there’s an understanding of common interest and connection.

So are you saying that it’s less politically useful to say, “White women come for white women” than it is to say, “white evangelical women, reckon with your community,” or, “white Jewish women, reckon with your community”?

Right, and then to give a specific narrative that makes sense inside of those communities. I think there are some white, evangelical women who are articulating exactly that, who are saying, “No, this evangelical community is leaving these Christian principles aside, and that’s not who we are.” And maybe they are particularly noticing that because of their gendered experience of being subordinated in that space. That can matter.

Right. Womanhood matters within these subgroups, but it doesn’t necessarily tie all women to each other. Which I think can be really frustrating.

But the beauty of that is that these women in those spaces also can create agency over men in those spaces, right? What some white evangelical women are looking to do is not to just say, “Hey, white evangelical women, we should disagree.” But: “As white evangelical women, we should be redefining the whole space. We should be demanding different things from our church. From our church leaders. From our membership.” So again, their gender experience may be leading them to articulate these things, but in the end they often can move, not just the women in those spaces, but some of the men, too.

We got women’s suffrage because labor unions and farmers’ organizations finally signed on for the cause. They did that because of their women members, but the entire organizations signed on. Not just the women in them. And that’s what pushed the politics in this progressive women’s right direction [at that time].

I know it’s hard. I have so much empathy for trying to write this up as a journalist. This is really the core of my entire gender and politics class.

[Laughs.] Well, it’s hard to write about as a journalist and also hard to grapple with personally. I’m a white woman who truthfully doesn’t really have meaningful social ties to other white women who vote super differently from me. I’m Jewish, college-educated, grew up just outside an urban center and now live in an urban center. So how is the energy of someone like me best used?

Maybe it’s more important to have white women on the left to demand things of the people that they actually have leverage over. We keep asking white women to get other white women. Why are we not asking white women who are sympathetic to the left to come for those marginally sympathetic, tied-to-them-socially white men? It’s not about saying that white women who are on the left don’t have the obligation to do some work. It’s just not clear to me why the expected work that they would do would be to go get other white women [to whom they have no social ties]. It would be to identify “Who are your gettable white men?” And get them.

What you could do is be like, “I’m going to put effort into making sure that my Jewish community is really an active partner,” but you can say: “I feel this obligation, because those other white women are letting us down. I feel the obligation, but I’m not going to fulfill it by going after them. I’m going to fulfill it in a different way, in a more effective way.” The history of progressive change in terms of civil rights is not about getting all the white people on board. But it is about trying to get the should-be-sympathetic-but-maybe-aren’t-active groups of white folks actively on board. And, it turns out, that’s what matters. That’s what delivers the political goods. It’s what delivers elections, too. You’ve got to mobilize, and we do that through groups.

So I think the frame of the question is just a little off. Why would we send people after women they have no identification with, they have no commonality with. How about we send them for the people they do have commonality with?

REAL LIFE. REAL NEWS. REAL VOICES.

Help us tell more of the stories that matter from voices that too often remain unheard.

[ad_2]

Source link