[ad_1]

When I was a child, I often joined my mother in prayer at the shrine in her bedroom. The shrine looked to me like a doll’s house, a wood-and-glass scale model of a human-sized sanctum. It housed small bowls of rice, water and salt.

My late Japanese mother married an American in 1958, and despite her insistence that her children not speak Japanese for fear people would think we were foreign, she never gave up her Japanese religion. As the daughter of a priest in the Konko Church, she eschewed the Latter-Day Saints of my father and practiced a Shinto mindset, stubbornly and daily, alone at our home.

“Clap three times,” she instructed me, “so the kami know you’re here.”

Kami are Shinto spirits present everywhere — in humans, in nature, even in inanimate objects. At an early age, I understood this to mean that all creations were miracles of a sort. I could consider a spatula used to cook my eggs with the wonder and mindful appreciation you’d afford a sculpture; someone had to invent it, many human hands and earthly resources helped get it to me, and now I use it every day. According to Shinto animism, some inanimate objects could gain a soul after 100 years of service ―a concept know as tsukumogami ― so it felt natural to acknowledge them, to express my gratitude for them.

“Tell the kami-sama what you’re grateful for,” my mother would say to me, referring to God or the supreme kami, “and what you want.”

I had my mother in mind when I watched Marie Kondo’s Netflix show “Tidying Up” for the first time. In each episode, Kondo, a professional organizing consultant, instructs her clients to identify the objects in their homes that “spark joy” and devise a plan to honor those objects by cleaning and storing them properly.

She also encourages people to part ways with the objects that fail to spark joy, but not before thanking them for their service. The way Kondo pledges gratitude for the crowded houses she visits, and thanks the clothes and books and lamps that serve so much purpose for the families seeking to declutter their homes, struck me as a powerfully Shinto way of conducting life.

My mother could pick up any of the treasures in our small home and tell me their story, how much joy she said they gave her. A sparrow figurine reminded her of the birds that came to our feeders. There was the small glazed ceramic pitcher my brother made in fifth grade. A plain black cup was a medieval antique from her father’s church. Each one was dusted regularly and displayed with care.

Kami are Shinto spirits present everywhere — in humans, in nature, even in inanimate objects. At an early age, I understood this to mean that all creations were miracles of a sort.

The Shinto mindset was present in everything my mother did. Both she and my father grew up in poverty, she in rural Japan and he in a coal mining town. After they married, they didn’t have much money compared to others in our neighborhood — my father supported us on his Navy retirement salary and by selling jewelry at JCPenney’s — but we had a nice, if modest, home.

Whereas my father’s response to the wealth we had resulted in Neiman-Marcus credit card debt and a garage stuffed full of 30-plus years of cheap goods, my mother disliked the disposable, acquisitional mentality of Western culture. She recycled long before it was popular, repurposing objects others might throw away. She washed out plastic bags and reused them, because a great deal of energy and materials had gone into their manufacture. She composted. She saved rainwater. She took glass bottles and made them part of her garden display. She cut up old shirts and used them as rags, saved the buttons for sewing projects.

I’m using my mother as an example, but it’s cultural to imbue objects with a sort of dignity. Japanese culture, like any, is not monolithic, but the expectation to respect where you live and work — and therefore other people — is ingrained into many Japanese households that practice Shinto traditions. Treasuring what you have; treating the objects you own as not disposable, but valuable, no matter their actual monetary worth; and creating displays so you can value each individual object are all essentially Shinto ways of living. Even if you don’t have the space for shelves of books or can’t afford a dresser with enough drawers, make what you have work for you, instead of being unhappy that you don’t have more.

It’s why some school children in Japan clean their cafeterias. It’s why you saw some Japanese people picking up trash after the World Cup. It’s not because they are genetically tidier and more respectful. It’s because many are culturally taught that people and places and objects have kami.

So when people online began condemning Kondo and her KonMari method, the disparaging memes and criticism read to me less as a simple sentiment of “eh, not for me” and more as an outright cultural attack. On Facebook and Twitter, otherwise empathetic and culturally sensitive peers made fun of Kondo in starkly xenophobic terms.

White writer Anakana Schofield helped kick off the backlash with a snarly tweet that she expanded into a Guardian article, in which she takes umbrage with Kondo’s method of tapping on books to wake them up. “Surely the way to wake up any book is to open it up and read it aloud,” she writes indignantly, “not tap it with fairy finger motions — but this is the woo-woo nonsense territory we are in.”

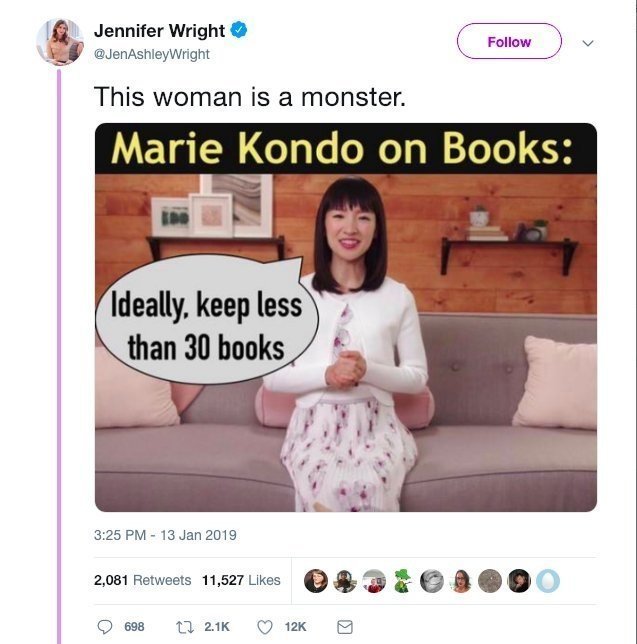

As online fervor drenched in not-so-subtle racism swelled, blatant misinterpretations of Kondo’s method proliferated. I saw a false meme claiming Kondo wanted to limit people to owning only 30 books probably 50 times in a single day. I kept commenting, This is not true. She doesn’t care how many books you keep, as long as they’re not causing you misery.

In a piece titled, “Keep your tidy, spark-joy hands off my book piles, Marie Kondo,” Washington Post book critic Ron Charles wrote: “And suddenly people have noticed the dark side of Kondo’s war on stuff: She hates books.”

Again, Kondo does not begrudge anyone piles of books or anything else for that matter, as long as those piles are not causing sweat-filled panic attacks. And if they are causing people to feel that, surely nobody can begrudge them getting Kondo’s help in giving the piles away.

Kondo eventually addressed her critics in a statement. “It’s not so much what I personally think about books,” the best-selling author said. “The question you should be asking is what you think about books. If the image of someone getting rid of books or having only a few books makes you angry, that should tell you how passionate you are about books, what’s clearly so important in your life. If that riles you up, that tells you something… That in itself is a very important benefit of this process.”

But the vitriol was never just about the books. Buzzfeed writer Anne Helen Petersen blamed Kondo, in part, for crushing the spirit of the millennial generation. “The media that surrounds us — both social and mainstream, from Marie Kondo’s new Netflix show to the lifestyle influencer economy — tells us that our personal spaces should be optimized just as much as one’s self and career. The end result isn’t just fatigue, but enveloping burnout that follows us to home and back,” she wrote.

Petersen’s analysis failed to recognize that the opposite is true. Kondo teaches that material goods are not a means for attaining happiness and urges people to appreciate what they have, a method she intends to lead to contentment, not burnout.

It’s as if Petersen, like so many other detractors, depended on the memes providing shallow and incorrect summaries of Kondo’s method rather than cull opinions from actually watching the Netflix show or reading the book upon which the series is based. Either way, the mostly white people who are not professional organizers had no problem telling Kondo, a woman of color and highly recognized person in her field, that her approach is objectively wrong.

I had never seen quite this level of concentrated venom directed toward a self-help/home decor person. Not Martha with her thousand-step craft projects. Not Rachel Hollis telling “girls” to wash their faces and to judge friends based on whether they can keep off weight. Not even Gwyneth when she told everyone to steam their lady parts and wedge a jade egg inside. All received backlash, but none garnered as much misguided indignation as Kondo, long after she managed to sell two million copies of her debut book.

Even though Kondo delivers her dictates in the gentlest ways possible (I watched her show with the subtitles on; they kept saying she cooed), the message was clear to me: White people are comfortable when a woman of color takes on a stereotypical service role, but they are uncomfortable when a woman of color deigns to upend our unspoken societal rules. Even if she gets a bunch of men, who’ve left all the emotional labor of managing the daily stuff of living to their wives, to actually pitch in — even if people have padded too much into their lives and she helps them enjoy what they have again — it’s not enough. Unconsciously or consciously, Kondo had struck a nerve.

My dad used to say, ‘The Japanese do everything backward.’ Even when I was little, the phrasing bugged me, though I couldn’t articulate why. Now I know. It meant that the Japanese were the wrong ones, the ‘other.’

My dad used to say, “The Japanese do everything backward.” Even when I was little, the phrasing bugged me, though I couldn’t articulate why. Now I know. It meant that the Japanese were the wrong ones, the “other.” Westerners were at the center of his universe, just as Western values are at the center of the memes disparaging the KonMari method. In effect, online criticism sounds like my father’s: The Japanese are backward. A woman of color could not possibly help white people live better lives, because that might mean she is better.

It’s OK to say, “Hey, I like my clutter. It causes me no anxiety, so I’ll pass on Marie Kondo’s suggestions.” And it’s true that people with compulsive hoarding tendencies may be unable to undertake her style of cleaning without guided help. Her method is not for everyone. But to wholesale dismiss her suggestions with xenophobic language and unadulterated Western hubris is to dismiss an entire ancient cultural tradition that has harmed exactly no one.

After my mother died, my father coped by collecting antiques and vintage objects with a vengeance, plates and glassware and art that he squirreled away into the garage and cabinets. His displays became cramped, never dusted, forgotten. Papers and clothes piled up everywhere and spilled onto the floor. It grew out of control quickly; there was no longer peace.

It was only then that I fully appreciated how hard my mother had been curating our lives — KonMari-ing our house — so we could feel the kami.

[ad_2]

Source link