[ad_1]

In a rapid-fire question-and-answer portion of the first Democratic presidential debate Wednesday evening, each candidate was asked about the greatest geopolitical threat to the U.S.

Interested in Democratic Party?

Add Democratic Party as an interest to stay up to date on the latest Democratic Party news, video, and analysis from ABC News.

Multiple candidates mentioned nuclear weapons or nuclear proliferation, but Rep. Tulsi Gabbard, D-Hawaii — a combat veteran who served on the armed services and foreign affairs committees — went further, claiming that “we’re in a greater risk of nuclear war today than ever before in history.”

Gabbard’s language might seem hyperbolic, especially to Americans who as children may have participated in “duck and cover” drills amid fears of a Soviet nuclear volley during the Cold War. But experts are split on whether she’s actually that far off — with one saying the nuclear war threat is as dire as ever, and another calling Gabbard’s assessment “nuts.”

“It is not clear that the risk of nuclear war is greater than ever before, but it is clearly higher than it needs to be or should be,” Jon Wolfsthal, director of the Nuclear Crisis Group and former senior White House National Security Council official under President Barack Obama, told ABC News.

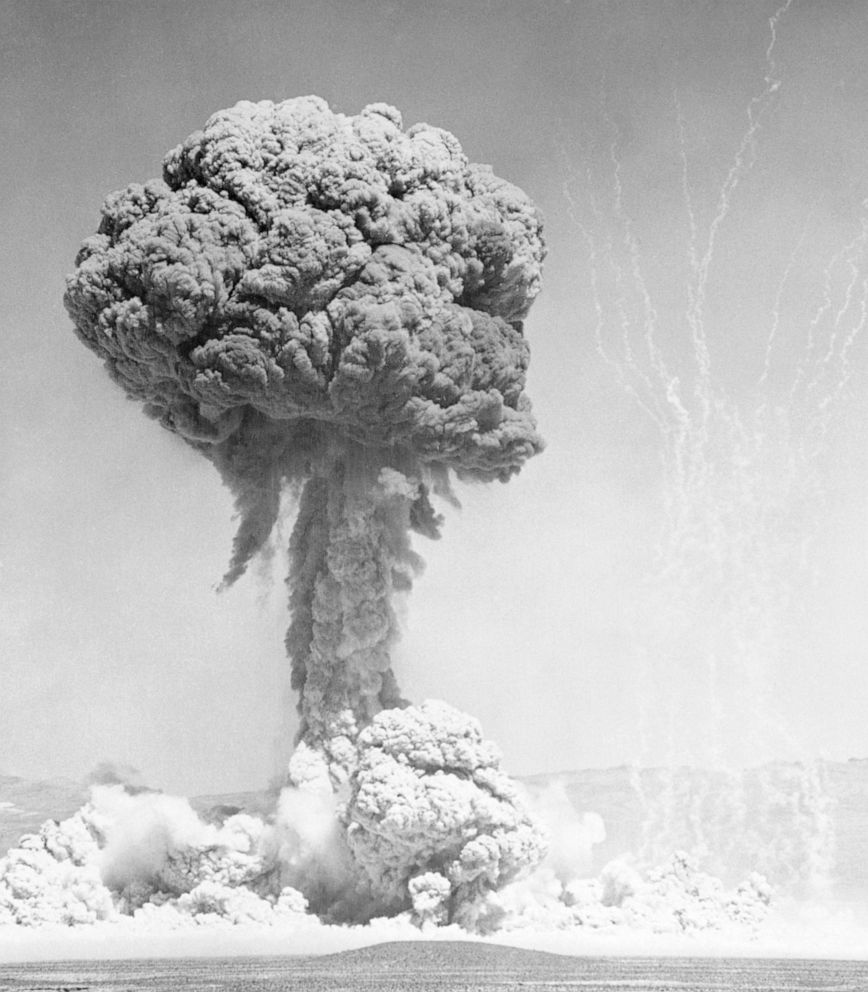

Bettmann Archive

Bettmann Archive

Wolfsthal noted that the unnerving “Doomsday Clock” created by the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists, which has tracked the threat of nuclear disaster since the late 1940s, is currently set at two minutes to midnight, where it’s been since January 2018. The Bulletin says that’s “as close to the symbolic point of annihilation that the iconic Clock has been since 1953 at the height of the Cold War” due to the dual threats of nuclear weapons and climate change.

“This suggests that things are as bad as they ever have been, but not worse,” said Wolfsthal, who sits on the Bulletin’s Science and Security Board.

In April, a United Nations expert on nuclear disarmament, Izumi Nakamitsu, warned the international body that the threat of nuclear weapons being used, “by accident or through miscalculation, is higher than it has been in decades.”

“This is due to a variety of interconnected factors,” Nakamitsu said, “chief amongst them being current geostrategic tensions and the emergence of technological innovations with strategic implications.

“Brakes on nuclear weapons use are progressively being removed, through the demise of transparency and confidence-building measures, through the use of dangerous rhetoric related to the utility of nuclear weapons, and above all, through the lack of dialogue between States possessing nuclear weapons and the erosion of communication mechanisms,” she said.

Wolfsthal pointed, in part, to the “tone and approach” taken by President Donald Trump with regard to “North Korea, Iran and elsewhere” as contributing to the crisis, as well as tensions with fellow nuclear power Russia over arms control treaties.

Before a diplomatic and personal rapprochement with leader Kim Jong Un, in August 2017 Trump threatened nuclear-armed North Korea with “fire and fury like the world has never seen” should it continue to threaten the U.S. Soon after taking office Trump pulled the U.S. out of the Iran nuclear deal, designed to keep the Islamic Republic from acquiring nuclear weapons, but has since used strong language to demand the country not attempt to develop them.

In a speech earlier this month, Gabbard reasoned that “regime change” wars had “exacerbated” the problem of nuclear proliferation, specifically how the value of nuclear weapons was reinforced to North Korean leaders after the international intervention in Libya, and said the U.S. was in a “new arms race” among the major powers, contributing to an almost unprecedentedly unstable nuclear world.

But Jon Alterman, senior vice president at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, isn’t buying any comparison of the danger today to that during the Cold War.

“It’s nuts,” Alterman said. In the Cold War, “not only did we have thousands of missiles pointed at the Soviets and they had thousands of missiles pointed at us, but we went into alerts several times.”

Alterman noted several hair-raising incidents nearly set the two superpowers off, including potentially world-destroying false alarms.

“I would argue there is a growing proliferation threat over the next several years, but to say that we’re now at the risk of nuclear war is to ignore all the times we were actually at risk of nuclear war,” he said.

Former ambassador Steven Pifer, a nonresident senior fellow in the Brookings Institute’s Arms Control and Non-Proliferation Initiative, appeared to agree with Alterman, citing Cold War close calls like the Cuban Missile Crisis.

“I believe that Rep. Gabbard overstated the case,” he said. “To be sure, U.S.-Russian relations are at their lowest point in 30 years, and the bilateral nuclear arms control regime — due to actions of both sides — appears to be collapsing. But the danger of nuclear war is not greater than ever before in our history.

“Things are not great now, and both Washington and Moscow should be working more actively to reduce the nuclear risk. But people should keep some perspective,” he said.

The White House did not immediately provide a comment for this report, but Trump has indicated he’s hardly blind to the dangers of nuclear war.

“When people talk global warming, I say the global warming that we have to be careful of is the nuclear global warming. Single biggest problem that the world has,” then-candidate Trump told The New York Times in March 2016. “Power of weaponry today is beyond anything ever though of, or even, you know, it’s unthinkable, the power. You look at Hiroshima and you can multiply that many, many times, is what you have today. And to me, it’s the single biggest, it’s the single biggest problem.”

[ad_2]

Source link