[ad_1]

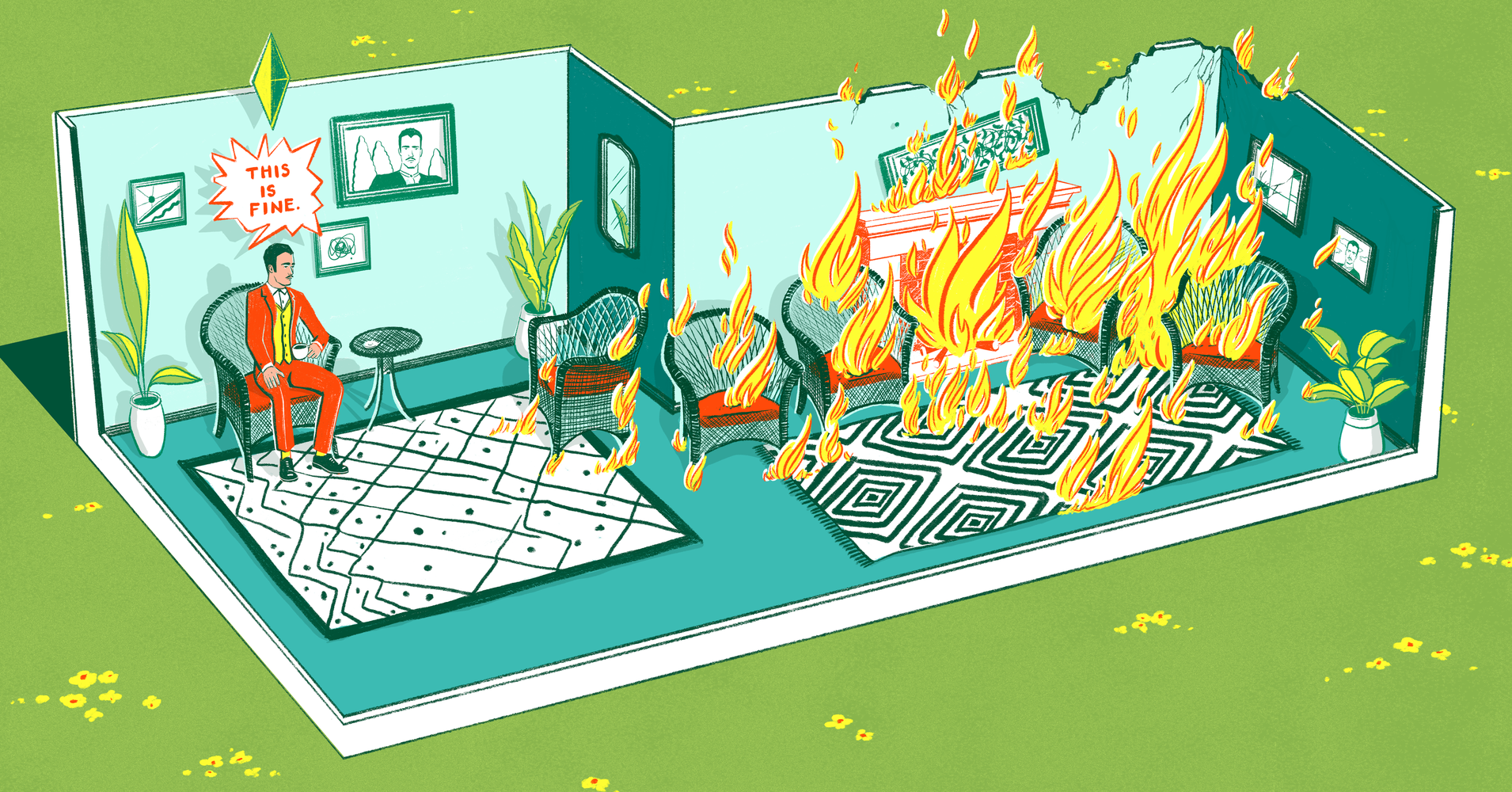

Mortimer Goth settles in to one of the 15 wicker chairs that have suddenly appeared by his lit fireplace. He feels strangely compelled to sit and remain seated, as if guided by an unseen hand, even as the room he’s in grows curiously hotter and hotter. Before he knows it, the chairs around him burst into pixelated flames. He’s on fire! He calls for help, but his wife, Bella, can’t hear him. She’s swimming in circles in their backyard pool, searching fruitlessly for a ladder that doesn’t exist.

For the uninitiated fiddling around their family desktop, the original version of “The Sims” was mostly about nurturing humanlike characters through life’s minutiae. For everyone else, “The Sims” was and is a game about death, about wacky, inconsequential death, about fiery death and watery death, death by starvation and death by electric shock and death by skydiving malfunction ― Mortimer and Bella’s worst recurring nightmare. And as the game evolved over the years, a kind of meta-game has formed around it: a subtle relationship between creative, death-obsessed “Sims” players and the game’s ever-adapting designers, keen on raising the stakes of the simulated lives we so easily ended.

Today, death on “The Sims” can feel harder and harder to come by. But it’s never impossible.

In the scenario above, the deaths of Mortimer Goth and his wife were no accident. They were the result of a human player deciding to set in motion a series of events that would lead to the inevitable demise of digital beings brought to life in a simulation game. That human player could have ushered Mortimer and his wife into a room and removed the door, watching as the Sims starved inside. The player could have prompted the characters to start making a feast with their cooking skill at Level 1, tempting a shoddy oven to burst aflame and engulf them. The player could have even neglected the couple’s guinea pig, only to have Mortimer pick it up and allow the rodent to administer one fatal bite.

But that player chose to cluster highly flammable chairs near the fireplace and hope they caught like tinder, and remove the ladder in the swimming pool once Bella, ignorant of the option of simply lifting herself out, dived in.

Back in the heyday of the game’s first iteration, everyone killed their Sims. I feel confident in stating this even without hard data to back it up: Killing Sims wasn’t exceptional behavior, it was the norm. Just look at the Reddit threads relaying depraved “Sims” activity with comments spooling into the thousands, or this Polygon article, where it is written, “It is a proven fact people love killing off Sims.”

“That was the only enjoyable way to play ‘The Sims’!” Maddy Myrick, 31, told me. She’d responded to my callout on Twitter, asking first-generation “Sims” players to explain the morbid habit of killing a thing you were ostensibly tasked with keeping alive. “Sometimes I would start a new family, convinced that I would let them live. But, inevitably, I quickly became bored with designing their house (which I was never able to finish).”

And so she killed them. Sims have died for less.

One of the most common tactics for killing a Sim, beautiful in its simplicity and effectiveness, is the “murdershed” method, as one “Sims” player described it: the doorless room.

“My favorite thing to do was lure my Sims into a seemingly normal space and then take away its exit,” my colleague Sara Boboltz confessed in a direct message. “So, I’d make a tiny house and take away the door. I’d make a pool and take away the ladder. Make a two-story house, take the stairs. You get it. Sometimes my Sims would be teachers I didn’t like.”

“I made a guy who was a compulsive neatfreak,” Reddit user vsanna wrote in a comment that rose to the top of its thread. “Put him in a really surreal little house with a wedding buffet and a hamster or something, deleted the door. Eventually he went insane from lack of cleanliness and depression over his little rodent friend dying, and starved to death once the banquet rotted. I put the resulting urn in the room. I then repeated an identical scenario several times, always keeping the urns in the room.

“Eventually the tenth iteration of this guy is up all night, every night, terrified of a parade of ghosts of himself.”

Our penchant for serial killing has not gone unnoticed at “Sims” headquarters. According to “The Sims 4” senior producer Grant Rodiek, who’s been with the company since 2005, the latest version of the game registers around 28,000 Sim deaths per day.

“I think [killing Sims is] a way players can express ultimate control over a thing. It’s funny, mischievous, dark, without being grotesque,” Rodiek said. “It’s a kinder, gentler method of using a magnifying glass to burn insects.”

Between life and death in “Sims 4,” there’s still no single path to playing. The vastly open-ended game nudges you toward certain goals — meeting your Sims’ physical needs; securing them a means of making money — but no task or accomplishment is necessarily required.

Rodiek and his colleagues have had a lot of time to analyze the preferences and behaviors of “Sims” players. He’s whittled users down to a handful of types: There are the “aspiring Frank Lloyd Wrights” who love tinkering in the game’s Build mode; the Create-a-Sim artists who painstakingly remodel favorite characters or celebrities in digital form, or the narrative writers who play out classic storylines (think: mysterious new kid, star-crossed lovers, etc.) in Live mode.

“And then you have the sort of people … we call them deviant players,” Rodiek said. “People who like to mess with their Sims, people who like to poke at the system, people who like to have fun and break the game and do weird stuff.” (These categories, I’d add, are not necessarily mutually exclusive.)

In the early years, these players, in an effort to discover all the ways they could ruin their Sims’ lives, might’ve swapped stories with friends about building murder houses and endlessly upping their budgets for DIY torture devices using the “rosebud” money cheat.

As the internet’s capacity to bring people together has evolved since the early 2000s, so have user-created parameters to keep gameplay interesting. Forums hold lists of restrictive challenges, which can involve everything from having one Sim birth 100 babies to re-creating consecutive historical eras with each generation of a family. On YouTube, players show themselves re-enacting “The Hunger Games” or building lengthy mazes meant only to make simulated life harder for their tiny humans. (One Simmer who orchestrated 12 seasons of Sim “Hunger Games” — complete with training days and sporadic gifts of food like apples — was recently hired on by Electronic Arts as an assistant producer.)

Over the years, the current base game — there are four total now — is supplemented with expansion packs to provide new ways to play the game — and kill your Sims. Rodiek said it’s the first thing developers plan out with each new expansion, along with new places for your digital hedonists to hook up.

Much-beloved YouTuber “Call Me Kevin” has a series showcasing his comically deadly restaurant in “Sims 4,” where unskilled chefs serve up the sometimes-fatal pufferfish nigiri introduced in the “City Living” expansion pack. It’s the only thing on the menu. Watching him play, you see Sims dining casually together, only to be interrupted when one diner clutches at their throat and falls head-first into their food. He’s amassed quite the graveyard behind the restaurant, complete with a coffin that you can WooHoo in — Sim-speak for sex.

Part of the widespread appeal of killing Sims might be that the actual moments of their demise aren’t particularly disturbing. Generally, dying Sims just drop or crumple to the floor in distress, disappearing altogether in some versions of the game. Coming across a hungry cowplant provides the bizarre and delightful visual of a giant flower consuming a Sim, but there’s no blood or errant limbs left behind. In a fire, Sims might become visibly odorous as their Hygiene levels plummet, but that’s about it — no gore or horror-movie theatrics.

There are some deaths “The Sims” avoids altogether.

“We don’t let toddlers burn to death,” Rodiek said. “That’s just gross. That’s not funny, there’s nothing humorous there. We don’t let dogs burn to death because like, again, that’s gross.”

Eventually, the grim reaper, who can talk to but sadly not have children with Sims, comes to collect your character’s soul, leaving an urn or gravestone in the Sim’s place. The reaper himself has a cellphone or a tablet, ostensibly to process the Sim’s soul, or something. It’s all a little goofy.

The fact that players have long brought Sim death on themselves is all a part of probing the edges of an established world.

Philosophy professor C. Thi Nguyen, who has written extensively about the philosophy of games, likened the act of killing Sims to the innocent phenomenon of “speedrunning,” where players try to complete a given game as fast as possible.

“One of my favorites is a speed run of ‘[Super] Mario [Bros.]’ where you try to get zero points … even though the traditional goal of ‘Mario’ is to max out your points. Trying to get to the end as fast as possible with zero points is actually much harder and much weirder,” he said. “You’re playing the game in an unintended way, which, for some people, I think it makes them feel more creative.”

“The system seems to tell you, ‘Look, the point of this game is to take care of the Sims,’ and all the tools that are given to you are given to you to take care of your Sims,” he said. “So if you want to kill your Sims, you have to do kind of creative and unexpected things and kind of remix the game.”

However, Nguyen said it was also possible that, for the players who like “The Sims” for its narrative possibilities and engage with “the fiction of the game,” explorations of death could have deeper personal significance.

“It may vary from player to player, but I think from talking to a lot of players it’s actually about the creativity of using the system for a new purpose,” he said.

Whatever the explanation, the game’s creators have come to understand that we use “The Sims” not just to simulate life, but to play God. And it’s impacted the way the game has shifted, from “Sims 1” to “Sims 4.”

The first two versions of “The Sims” ― which Rodiek described as “disastrously hard” ― made it easier for the Goths to expire outside of a player’s purview. Direct Sim-on-Sim homicide isn’t possible, so accidents were more often fatal: a grilled cheese that burns down the house, a malfunctioning skydiving simulator, or a fatal shock delivered to a character standing in a puddle during an electric repair. In “The Sims 2,” simply being in the front yard at the exact time a satellite falls to Earth could be the end of a Sim’s brief journey.

But nowadays, compared to “Sims 1” and “Sims 2,” it’s a lot harder to deliberately kill off dear Mortimer and Bella. Anyone coming to “The Sims 4,” the game’s latest version, might notice their characters can now easily hop out of a pool, ladder or not. It’s a change that came with “The Sims 3,” effectively eliminating one of the preferred manners of Sims murder.

“I love how funny and surprising it is to say, ‘Hey, we as a team recognize what you’re doing and, ha-ha, we flipped the switch,’” Rodiek said. The decision was born out of developers’ desire to further up Sims’ intelligence and self-sufficiency with each new version. Players, he said, “got pissed at this.”

“Basically, our thought was if Sims are smarter, and if Sims are less likely to just frickin’ die all the time, well, maybe they’re smart enough to pull their asses out of the pool,” he said, noting that you can still kill them from exhaustion if you build walls around the pool. “They’ll still fart at the wrong time and they’ll still just pass out in a pool of vomit if they’re tired enough and the timing is wrong, but that, at least, is a win for them.”

Now, if you leave them unattended, “your Sims will basically default to neutral,” Rodiek said. Players can worry less about making sure everyone has had a bathroom break or a meal. If you don’t direct your Sim to do it, they’ll likely figure it out themselves.

“Our tagline was, ‘We want to move past peeing,’” he said of shifting Sims’ needs beyond basic survival. “However, for them to really succeed, you have to nurture them. And nurturing your Sims comes from more emotional, higher-level fulfillment.”

Now, Sims have aspirations generally based on interests or specific actions: One Sim might want to become a tech genius, while another wants to become the neighborhood enemy. Fulfilling these wishes results in rewards that make the Sim better.

I’m usually a gentle “Sims” player, nurturing my families into fulfilling home lives and careers, watching as they level up in activities like baking and guitar playing, occasionally tossing in a love affair here and there. For the purposes of this article, though, I set out to kill as many Sims in “Sims 4” as I could.

Not wanting to delete doors and watch my Sims starve, I fell back on faithful killing strategies, like the classic fire scenarios. There were newer tactics I could try, too: In “Sims 4,” even Sims’ emotions, taken to the extreme, can be fatal; their hearts can explode from sheer rage or cease beating from hysterics.

In “Seasons,” the most recent expansion pack, Sims who are skilled in flower arranging can whip up a mysterious plant, the scent of which ages or kills its recipient. A video from website Sims VIP illustrating this particular death demonstrates the cruelty: At first, an elder Sim is pleased to be receiving a gift. But upon realizing his bad luck, he becomes angry, shouting out “Narb!” He wipes his brow, swoons to his knees, and even checks his pulse one last time before the grim reaper arrives.

“Seasons” also allows the possibility of death by freezing or overheating, or getting struck by lightning. New kinds of warnings tip you off to these sorts of ends: The game indicates via a Sim’s “moodlet” that your electronic buddy might die if he doesn’t get out of the blizzard, or change out of his snowsuit during a heat wave, or run in from the thunderstorm.

One of the suggested ways to murder your Sims is through overexhaustion, though once a Sim becomes “uncomfortable,” many actions, like jogging, become unavailable to a player. In “Sims 4,” more Sims simply die of old age than tragically before their time: Age accounts for 30.5 percent of deaths in the game, compared to the 11 percent who die of hunger; the 10.7 percent who drown; or the 10.6 percent who die in a fire, according to statistics provided by Rodiek.

Maybe I’m unpracticed, but I couldn’t murder my Sims. I made one Sim flirt with her husband’s dad in front of her husband, enraging the husband until the spouses became enemies, then nemeses. I had them all fight — illustrated by a cloud of dust and occasional flashes of limb — but it only made them a little dazed. I had them all pee themselves, then installed a shower and had them all walk in on each other, but no one reached the deadly “mortified” level of embarrassment. I made the dad swim in the pool in wintertime, but he kept getting out once he started freezing. Without resorting to the walls-around-the-pool method Rodiek mentioned, I couldn’t play God quite like I used to.

Defeated, I had the enraged husband and wife divorce before closing my game. It seemed only fair. When I opened up “Sims 2,” however, I found that one installation of the “shoddy fireplace” did the trick in no time. My Sims freaked out and wailed, too frantic to obey my requests for them to stand directly in the flames — but the blaze got them in the end.

Electronic Arts

Stakes, Rodiek acknowledged during our interview, are what make “The Sims” fundamentally interesting. Making death a part of the game from the start provided those stakes.

“It is really great when people have a Sim that they really care about, and they care about how they orchestrated their life, and they see them raise children, and maybe get a divorce, and then their children grow up and then they die. They go, ‘Oh, man, I could just re-create them, but it will never be that Sim.’”

“Our game is about creating weird, quirky, erratic, strange little humanlike characters that we want you to care about deeply,” he added.

In a perpetual quest, developers hope to keep inching “The Sims” toward a better reflection of real life and death, to keep raising the stakes and allowing customization in ways that matter to players.

In 2016, “Sims” released an update that expanded the possibilities of gender expression among characters, no longer restricting certain hair, makeup or clothing items to one gender or another and allowing players to select whether a Sim could impregnate others or get pregnant, regardless of outward appearance. Similarly, Rodiek said, creators are discussing the possibility of incorporating Sims who are deaf or hard of hearing, blind, or use a wheelchair. To help develop these, the team has been talking to players who have similar experiences.

“In actually talking to these players, talking about how it affects their lives, we’ve been thinking, how can we reflect this in a way that works in our game?” he said. “That’s the stuff we’re actually looking into that we really want to figure out, because it’s scary to get it wrong, but I think it’s so important if we can get it right.”

In terms of death, Rodiek said he could envision developing a kind of long-term, terminal disease within the game from which Sims can’t recover (but, seriously, don’t ask him about it on Twitter, because they’re not making this right now).

“I could see us approaching that in sort of a generic way that we’re not saying that it’s this specific cancer. But we’re basically saying that your Sim has something that can’t be cured and they will die before their time as a result of that,” he said. Maybe, he added, it’d be an option players could toggle on or off.

“I think it’s a reality of life … in a way that is like, yes, it’s real, and yes, it’s sad. But maybe for someone who wants it, it’s cathartic or its interesting and it helps you tell a story,” Rodiek said. “Those are some of the things we’re trying to grapple with and talk to our players about how to get right. And it’s terrifying, but it’s really cool if we could do it.”

Illustration by Tara Jacoby for HuffPost.

[ad_2]

Source link