[ad_1]

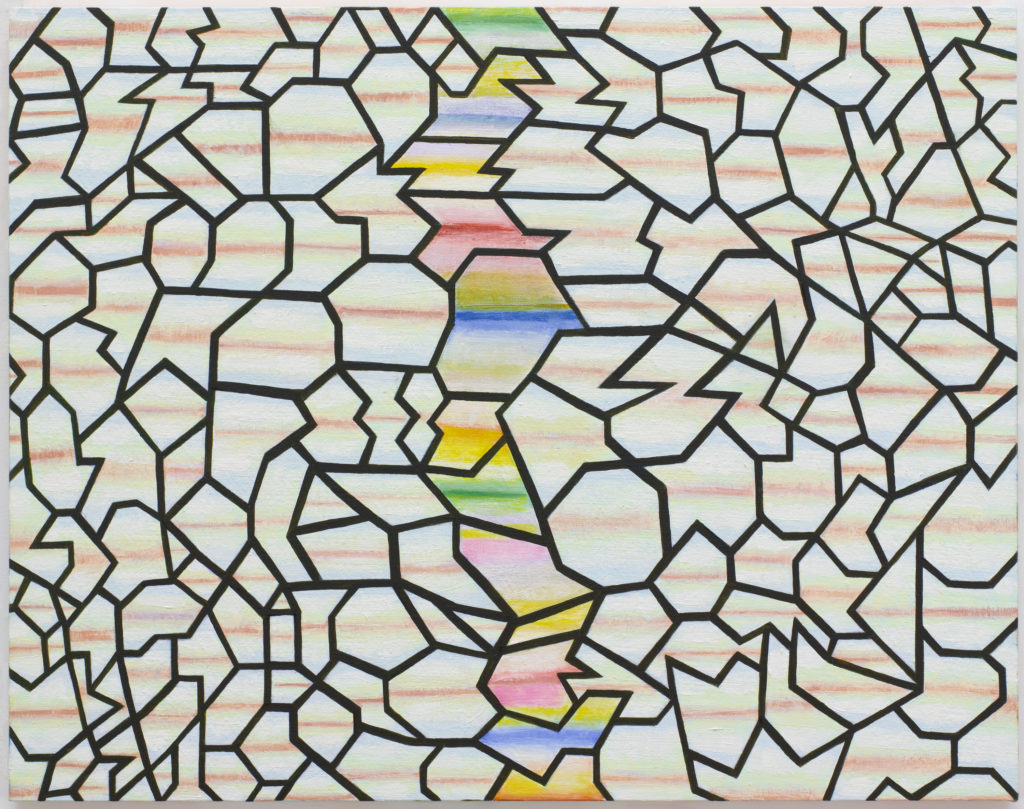

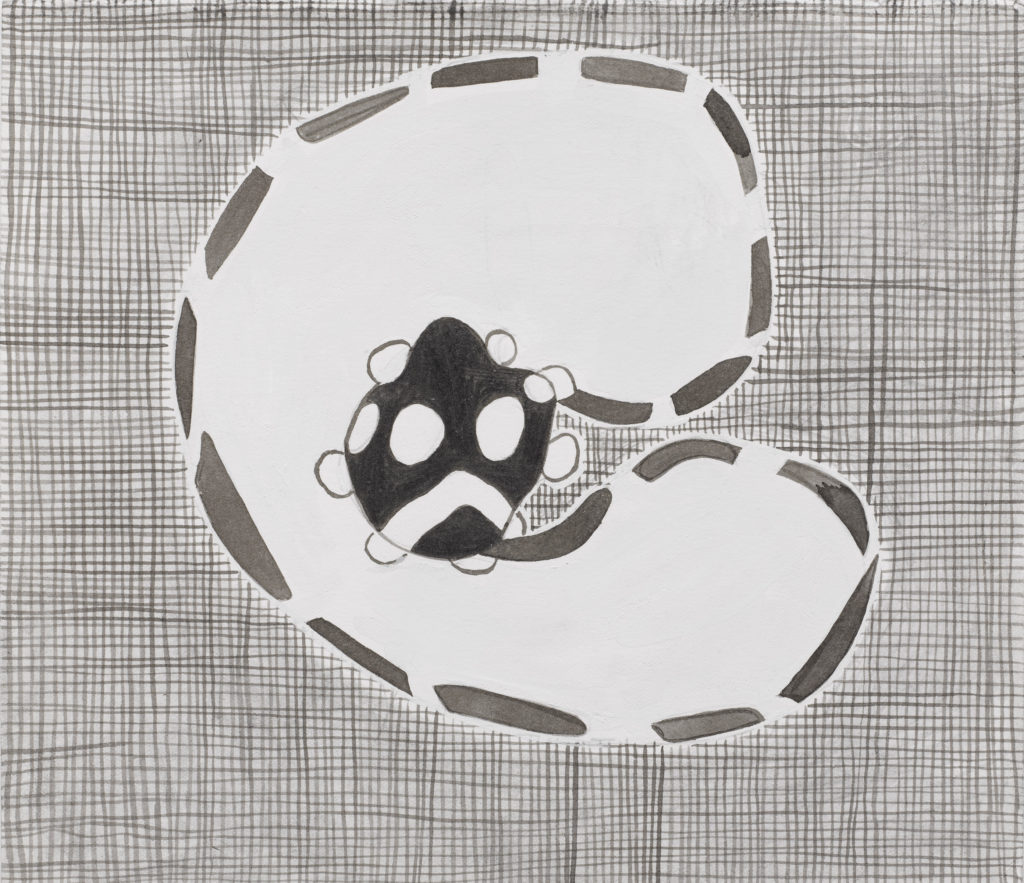

Thomas Nozkowski, Untitled (9-46), 2014.

©THOMAS NOZKOWKSI/KERRY RYAN MCFATE/COURTESY PACE GALLERY

Thomas Nozkowski, whose quiet abstract paintings, drawings, and prints evoke notions of landscapes and cosmic forms, has died. Pace Gallery, which represents the artist who was born in 1944, confirmed the news.

Nozkowski’s paintings were often based on natural scenes that he observed, but rarely did they reveal their source material. (He never titled his works beyond a number given to each one.) As a result, describing his vision could be a challenge. In Artforum in 2000, Barry Schwabsky wrote, “Art is often said to put language to the test, and rarely is that quite as true as in the case of Nozkowski’s paintings.”

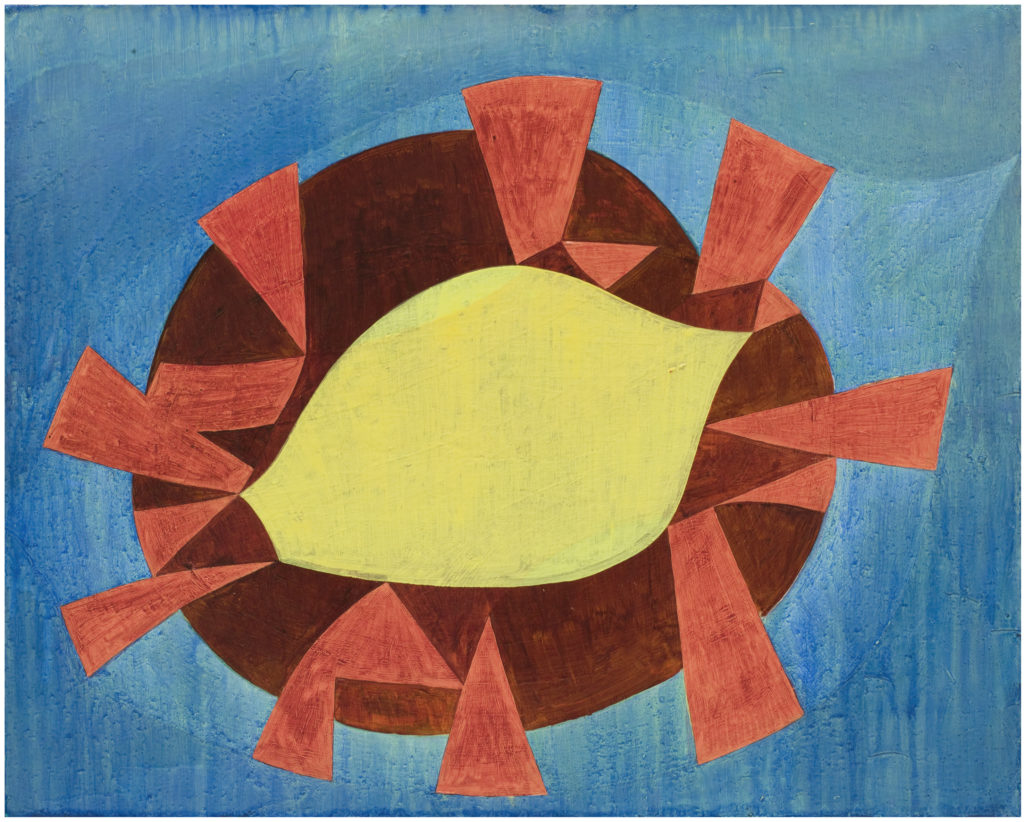

With their Matisse-like color schemes and Miro-esque organic forms, Nozkowski’s works recalled places or things their creator had glimpsed in the world. He described his paintings as memory devices. “By associating a color, a sign, or a shape to a memory, the more we own and can hold onto it,” Nozkowski told ARTnews in 2016.

[Read a 2016 Q&A with Nozkowski.]

Nozkowski began painting during the 1960s, when Conceptualism was in vogue and his medium of choice was considered unfashionable. In the years shortly after he began creating mature works, colleagues in New York responded to the stylistic shift by experimenting with painterly process—Jack Whitten, for example, began pulling acrylic across canvases using a squeegee, and Lynda Benglis contended with the three-dimensional qualities of paint by pouring it to make sculpture. Nozkowski’s innovation was to dramatically size down the non-figurative compositions associated with the Abstract Expressionists and to work on a small scale, rendering his abstractions down-to-earth and un-precious. The washes that acted as backgrounds for his compositions were often left uneven, so that droplets of paint appeared to have formed on his canvases.

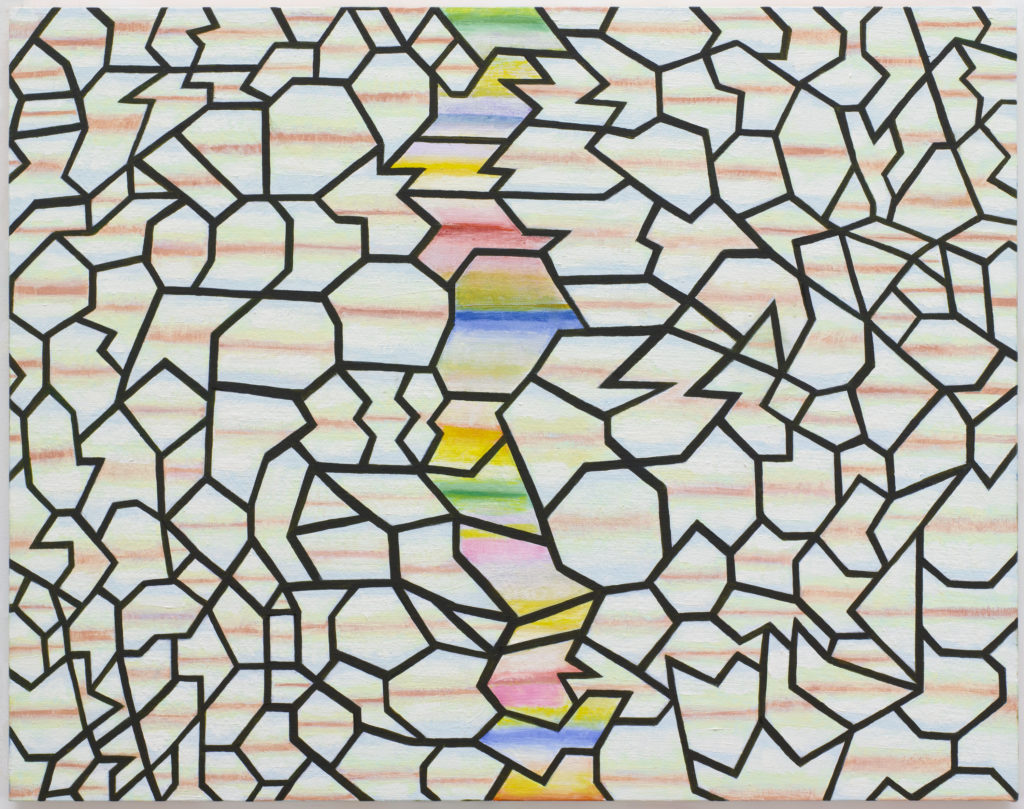

Thomas Nozkowski, Untitled (7-10), 1992.

©THOMAS NOZKOWSKI/TOM BARRATT/COURTESY PACE GALLERY

One of Nozkowski’s preferred formats was a 16-by-20-inch prepared canvas, on which he painted blobby circles and grid-like patterns, sometimes on top of thin washes. Had they been painted at large scale, the starburst- and platelet-like forms might have more visual drama—but Nozkowski was content to resign himself to placidity and understatement, so that viewers could find energy within them on their own.

He often described the decision to do so as a reaction to work by Jackson Pollock, Barnett Newman, and the like, who produced monumental canvases that were weighty in every sense of the term. “For political reasons, I found the kind of large scale, macho-man abstractions of early SoHo beneath contempt,” he told Artspace in 2015, decrying certain artists’ tendency to decide in advance how their canvases might look.

Because of their modesty—and in spite of having been featured in more than 75 solo exhibitions—Nozkowski did not receive widespread recognition for much of his lifetime. Among his biggest shows was a 1987 survey at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., with 24 paintings on view. (That show went on to travel to the Edwin A. Ulrich Museum of Art in Wichita, Kansas.) Nozkowski also appeared in the main exhibition of the Rob Storr–curated 2007 Venice Biennale.

Thomas Nozkowski, Untitled (N-78), 2010.

©THOMAS NOZKOWSKI/KERRY RYAN MCFATE AND TOM BARRATT/COURTESY PACE GALLERY

In time, certain critics and fellow painters became outspoken proponents of Nozkowski. Last year, John Yau, who published a book about the artist in 2017, wrote in Hyperallergic that Nozkowski was “still to be recognized for being equally courageous and cutting-edge.” Yau cited the younger Chris Martin and James Siena as two of Nozkowski’s fans.

Nozkowski was born in 1944 in Teaneck, New Jersey. In interviews, he described coming from a working-class background and not realizing he wanted to be an artist until one of his school teachers—a former Abstraction Expressionist “of no real art-historical import”—influenced him to move to New York after high school. He attended Cooper Union because it was free, and when he graduated, he started out as a sculptor, exhibiting some of his earliest works in group shows at the storied Betty Parsons Gallery. Not long afterward, he transitioned to painting.

For more than four decades, Nozkowski painted almost every day, often in his studio in upstate New York. Speaking to ARTnews in 2016, he described continuing to come upon new discoveries in the studio. “For me, there’s always something new to find, something new to do,” he said. “I certainly hope that lasts forever. It feels like it will.”

[ad_2]

Source link