[ad_1]

Why did it take two months for Georgia to charge Gregory and Travis McMichael with murder and aggravated assault in the shooting death of Ahmaud Arbery?

The father and son benefited from legal cover granted by two often misunderstood state laws, which can both separately prompt disastrous, deadly outcomes.

The first, Georgia’s version of a “stand your ground” law, should be familiar to anyone who followed the trial (and acquittal) of George Zimmerman after he shot and killed Trayvon Martin, an unarmed teenager, in Sanford, Florida, in 2012.

Georgia’s variant, adopted in 2006, states that citizens have “no duty to retreat” before using deadly force to defend themselves.

In theory, the law shields would-be victims who respond to a deadly threat with lethal force of their own. In practice, it’s nowhere near as clear-cut.

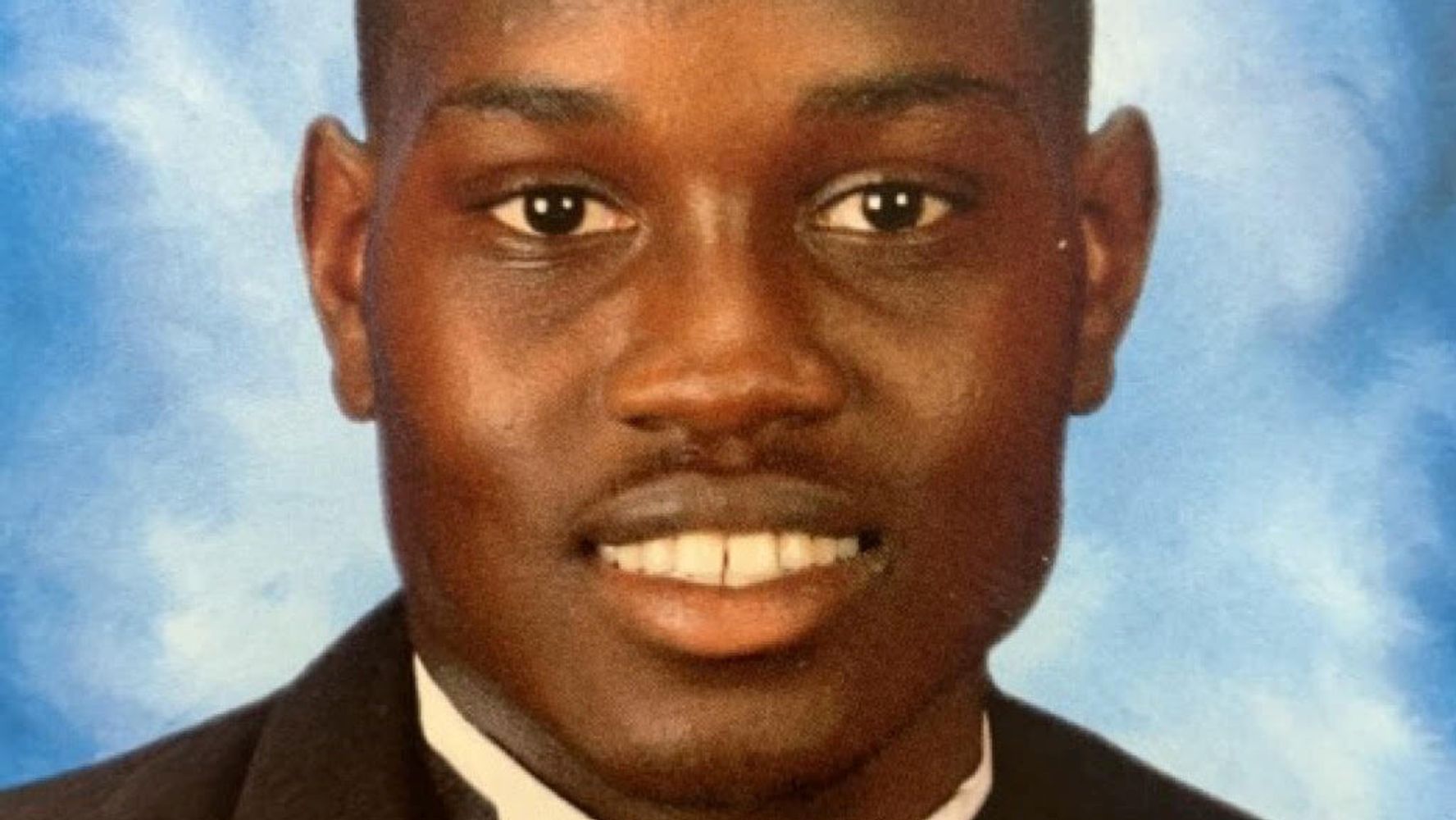

In Arbery’s case, the 25-year-old Black man was out for a Sunday afternoon jog when the McMichaels, both white men, decided the activity was suspicious and believed he might be responsible for a string of robberies in the area.

Armed with a .357 Magnum and a shotgun, the two drove after Arbery in their pickup and confronted him. Travis shot Arbery three times in the ensuing confrontation and killed him, which he now claims was in self-defense.

The law is problematic because it justifies deadly action in response to fear, Atlanta civil rights activist the Rev. Markel Hutchins told Georgia Public Broadcasting. And when fear is rooted in racism, it effectively makes racism a legal defense.

“Fear is oftentimes based on one’s own bias,” Hutchins told GPB in a 2012 interview. “So when you have public policy that literally lends itself to people being able to commit crimes or shootings under the color of law, because they’re reasonably afraid, it makes a bad public policy and puts the constitutional rights of so many people around the country in jeopardy.”

At least 25 other states have similar laws on the books, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures, a nonpartisan state policy organization.

The second law, commonly known as “citizen’s arrest,” empowers a private party to take someone else into custody if they know the person committed a felony and is attempting to escape.

That statute was specifically singled out by George Barnhill — one of two Georgia prosecutors who declined to press charges (and also later recused themselves) — in a letter to the Glynn County Police Department attempting to explain his inaction.

“It appears Travis McMichael, Greg McMichael, and Bryan William were following, in ‘hot pursuit,’ a burglary suspect, with solid first hand probable cause, in their neighborhood, and asking/telling him to stop,” Barnhill wrote. “It appears their intent was to stop and hold this criminal suspect until law enforcement arrived. Under Georgia Law this is perfectly legal.” (William accompanied the McMichaels but has not been arrested or charged.)

The circumstances are unlikely to be so clear-cut at trial.

The law also requires that the arresting citizen “use no more force than is reasonable,” Matt Kilgo — a Georgia defense attorney with no connection to the McMichaels’ case — told Vice News.

Given the outcome ― Arbery was shot to death ― that could be a difficult argument to make. “It’s going to come down to the facts,” Kilgo said. “What did they actually see him doing?”

Citizen’s arrest laws once served a valuable purpose, but that original purpose has long since expired, according to Ira Robbins, a law professor at American University’s Washington College of Law, who has studied citizen’s arrest laws.

“Citizen’s arrest arose in medieval times as a direct result of the lack of an organized police force and practical modes of transportation to get to the scene of a crime expeditiously,” Robbins wrote in a 2016 research paper. “Citizens had a positive duty to assist the King in seeking out suspected offenders and detaining them. However, citizen’s arrest is a doctrine whose time should have passed many decades — or centuries — ago.

“As official police forces became the norm, the need for citizen’s arrest dissipated,” Robbins added. “Yet these arrests are still authorized throughout the United States today, whether by common law or by statute.”

Calling all HuffPost superfans!

Sign up for membership to become a founding member and help shape HuffPost’s next chapter

[ad_2]

Source link