[ad_1]

Police and the politicians who protect them get most of the attention in the movement to defund or reform law enforcement. But there’s another, more powerful force that’s allowed law enforcement to use force on citizens, stop them without a warrant, lock them up for minor crimes and even raid their homes without a knock.

The Supreme Court has spent the last 50 years affirming the power of police to legally take such actions. The system built by officials and sanctioned by the court isn’t broken; it’s working just as intended.

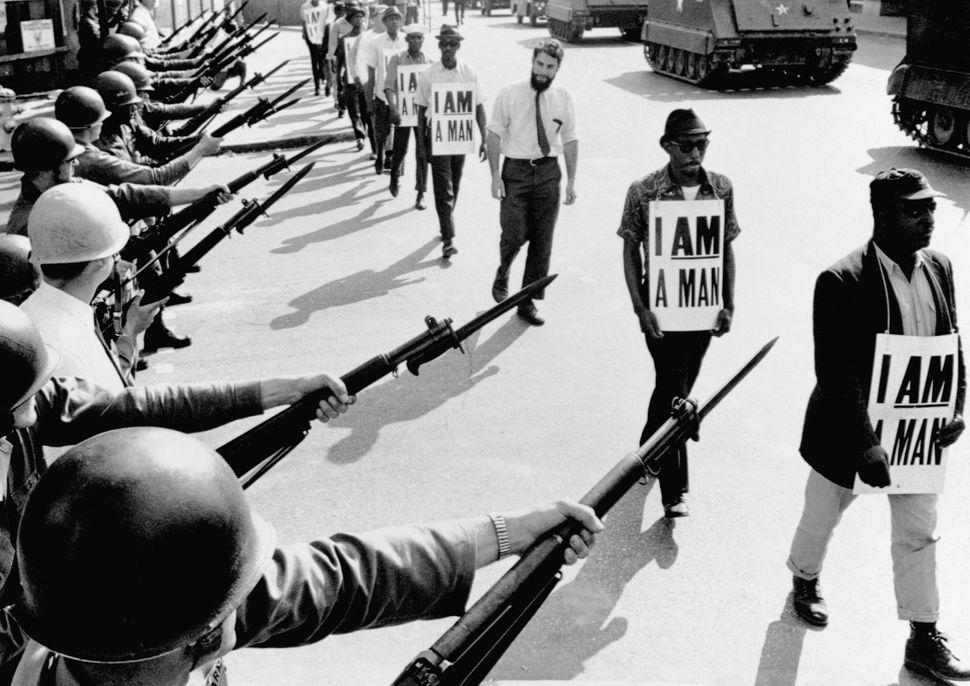

Beginning in 1968, amid rising white anxiety about the unrest in urban Black communities largely instigated by police brutality and crime, the court has signed off on controversial police practices marking a near total reinterpretation of the Fourth and Fifth Amendments while also creating a multi-step system protecting police from accountability when they are charged with abuse. The rulings provide the legal authorization for the policing system now deemed broken by politicians and protestors.

Court decisions joined by justices from all political persuasions enable police to stop and frisk anyone they deem suspicious; to stop any vehicle driver for any infraction even if the stop was a pretext for a different concern; to arrest anyone for any legal infraction, no matter how minor; to use force, including deadly force, even to enforce a speeding violation. And then the court has granted multiple layers of protection for officers and police departments from accountability from criminal and civil suits brought by victims of their actions.

Almost all of these cases are rooted in the interpretation of the Constitution’s Fourth Amendment, which protects “against unreasonable searches and seizures.” The court sided with police to rule that these practices were within those bounds.

“When a police officer initiates a traffic stop or a pedestrian stop, makes an arrest, applies for a warrant ― all of those behaviors and a number of others are subject to constitutional restrictions,” Seth Stoughton, an associate professor at the University of South Carolina School of Law and a former police officer, said. “And that means the Supreme Court creates a lot of the legal framework that applies to day-to-day policing.”

From the outset, a justice warned the rest of the court that the system it was approving was “a long step down the totalitarian path,” that would disproportionately target Black and brown communities ― specifically Black and brown men. The court approved those practices anyway. And the names recited at today’s civil rights protests are just part of the result.

Enter A New Regime

The legal regime justifying the nation’s broken policing system emerged in the long, hot summer of 1968. Days after the assassination of New York Sen. Robert F. Kennedy and a few months after riots erupted in Black communities after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. the Supreme Court issued an 8-1 decision in the Terry v. Ohio case.

Where previously the court had allowed police to stop and search suspects based on “probable cause,” the court switched gears in its near-unanimous Terry decision and gave the green light for police to temporarily detain and stop and frisk a suspect solely based on the lower standard of “reasonable suspicion.”

The case emerged out of Cleveland, Ohio, when in 1965 a white police officer saw two Black men during the daytime in the downtown commercial district looking into store windows. He suspected them of “casing” the store ― looking for a robbery target ― although he told the court he couldn’t put his finger on why. “They didn’t look right to me at the time,” he said. The officer confronted the two men, who declined to give their names when asked, which he said increased his suspicion. The officer grabbed them, pushed them against a wall and searched their bodies and clothes pockets. He found two pistols and arrested them.

At trial, John Terry, one of the two suspects, motioned for the court to dismiss the evidence of the pistol the officer found because the officer’s search and seizure of him violated the Supreme Court’s 1925 ruling that required police officers to have “probable cause” when initiating a search.

The Supreme Court, at the time under attack from everyone from the arch-segregationist Alabama Gov. George Wallace to Richard Nixon to the New York Times editorial page for a perception that its pro-defendant rulings coddled criminals, sided with police. The Court ultimately ruled that the officer did not have “probable cause,” but that his “reasonable suspicion” was enough to meet the demands of the Fourth Amendment. Police could now stop and search anyone that they thought could be a criminal, whatever that crime may be.

In his lone dissenting opinion, Justice William Douglas, a stalwart defender of constitutional civil liberties, wrote that the change in the Fourth Amendment made by the majority may be, “desirable to cope with modern forms of lawlessness,” but it, “should be the deliberate choice of the people through a constitutional amendment.” The result of the court’s decision to do otherwise, however, would be tyranny.

“To give the police greater power than a magistrate is to take a long step down the totalitarian path,” Douglas wrote. “[I]f the individual is no longer to be sovereign, if the police can pick him up whenever they do not like the cut of his jib, if they can ‘seize’ and ‘search’ him in their discretion, we enter a new regime.”

Police, particularly in Cleveland, Chicago and New York City, the latter of which submitted a brief in support of the officer in Terry, had already used the stop-and-frisk tactic for at least a decade before the court approved it. Unsurprisingly, this tactic was almost exclusively used to target Black people both in and outside of their own communities.

The court’s ruling never explicitly mentioned race, either of the police officer or Terry. But the court knew exactly what it was doing.

The NAACP Legal Defense Fund recognized the case had potential to unleash the police to target Black communities and sweep men and women into the criminal justice system. And it warned the Supreme Court in a brief that approving stop-and-frisk tactics would do untold damage to Black Americans as “reasonable suspicion” would very easily overlap with racial fear and anxiety.

“The essence of stop and frisk doctrine is the sanctioning of judicially controlled and uncontrollable discretion by law enforcement officers,” the brief states. “History, and not in this century alone, has taught that such discretion comes inevitably to be used as an instrument of oppression of the unpopular. It was so in the case of the search and seizure practices which the Fourth Amendment was written to condemn. We believe that that Amendment protects the unpopular, the Negro, and all our citizens alike, from subjection to the oppressive police discretion which stop and frisk embodies.”

To give the police greater power than a magistrate is to take a long step down the totalitarian path.

Supreme Court Justice William Douglas

The justices acknowledged they knew not only the danger of what they would approve, but the political climate in which they were acting.

Justice William Brennan, a liberal, wrote ahead of the ruling that he was “acutely concerned” that the court’s opinion would “be taken by the police all over the country as our license to them to carry on, indeed widely expand, present ‘aggressive surveillance’ techniques which the press tell us are being deliberately employed in Miami, Chicago, Detroit [and] other ghetto cities.” That could aggravate Black Americans’ resentment toward the police and make the court the scapegoat, he wrote.

The Nixon administration would soon launch a war on drugs that, when combined with the authority granted in Terry, would apply “reasonable suspicion” to anyone. The police would, as the court was told, direct their attention to stopping, frisking, detaining and assaulting Black men.

“Since that case, and in pretty much every case in which there’s been an issue of how much power police and prosecutors should have, the court’s been warned that if you give this power to the police they’re going to use it mainly against black people or brown people,” Paul Butler, a criminal law professor at the Georgetown Law Center, said. “And the court’s either ignored that concern, or discounted, or deflected, as it did in the Terry case.”

Police ‘Super Powers’

In the wake of the Terry decision, the court, including justices of all political persuasions, continued to authorize increasingly expansive powers for police despite warnings and clear evidence that the policing system they authorized was largely used to terrorize Black and brown communities.

In 1989, the court determined in Graham v. Connor that police could use deadly force if it was objectively reasonable. The 1996 Whren v. U.S. decision authorized police to racially profile when making traffic stops. In the Atwater v. City of Lago Vista case in 2001, the court said police can arrest anyone for any infraction even if the punishment for the alleged violation does not include any prison time. And in its 2007 Scott v. Harris decision, the court took the logic of Graham v. Connor further by ruling it reasonable for police to use deadly force against a suspect who fled a traffic stop related to a speeding ticket.

Butler refers to these court approved police tactics as police “super powers,” in his book “Chokehold: Policing Black Men.” These “super powers” acting in concert create the regime now denounced as a “broken system.”

For example, take the court’s decisions in Whren and Atwater.

In 1993, police in Washington, D.C., pulled over two Black men, Michael Whren and James Brown, after noticing that they had stopped at a stop sign for 20 seconds before making a right-hand turn without signaling in what the police deemed a “high drug area.” Whren and Brown were found with drugs on them and arrested.

Police stopped them for the minor traffic infraction of stopping too long at a stop sign and the failure to signal a turn, neither of which is an arrestable offense. And police admitted they did not care about the failure to signal. The turn signal infraction was a pretext to search for drugs. The fact that Whren and Brown were both Black was also a key part of the “reasonable suspicion” aroused in the arresting officers.

Did it matter that Whren and Brown were racially profiled or should the court only pay attention to the minor traffic infraction as an acceptable pretext for the traffic stop? The Supreme Court said no.

The officer’s “subjective state of mind,” that is to say, whether the officer considered the suspect’s race as a reason to pull them over, must be discounted, Justice Antonin Scalia wrote in a unanimous opinion. The only consideration should be the objective reason, meaning the traffic violation.

Due to the Whren ruling, courts can ignore whether police are picking and choosing people based on their being Black so long as police can present a legitimate traffic infraction for each stop.

“In the context of traffic stops, the fact that everyone commits traffic infractions almost every time they drive gives the police the ability to pick who they’re going to stop,” Stoughton, the professor and former police officer, said.

In Atwater, where an officer arrested and jailed Gail Atwater, a middle-age suburban white woman driving her children from soccer practice, for failing to wear a seatbelt. In a 5-4 decision, conservatives on the court ruled it constitutional for police to arrest anyone for any infraction even if the maximum underlying punishment for the infraction is a $50 ticket.

Add Whren’s approval of racial profiling to Atwater’s arresting power and police can now racially profile drivers and then arrest them for failing to signal a turn or even displaying an air freshener. Since police can seize assets from those they arrest, these combined powers, “provides a legal framework for among other things policing for profit or revenue policing,” according to Stoughton. That “focus on revenue rather than public safety needs,” shaped the racial bias of policing in Ferguson, Missouri, according to a 2015 Department of Justice report.

Eric Garner’s 2014 death at the hands of New York police is a example of these police “super powers.” Garner was stopped and arrested under the Terry decision for “reasonable suspicion” of selling a single loose cigarette. Under Graham v. Connor, police could use significant force against him if they thought he was resisting arrest and that they thought the proportion of the violence was “objectively reasonable.”

So while the chokehold used to kill Garner by officer Daniel Pantaleo may have been banned under NYPD rules, it would likely be acceptable based on the court’s interpretations of use of force. While Pantaleo was fired five years after he killed Garner, he was never charged with a crime.

No Accountability

Police officers who kill, maim or abuse people rarely face criminal charges. They are also rarely held liable in civil court. That’s because the Supreme Court has provided the already super-powered police with an additional super power: a shield from accountability.

The most well-known of these shields is the doctrine of qualified immunity that the court wholly invented in its 1967 Pierson v. Ray decision and radically expanded in multiple cases over the ensuing decades.

Qualified immunity protects police officers from civil liability lawsuits seeking monetary damages when the officers can show that they did not break “clearly established” laws. The idea proposed by the court, which invented this doctrine out of whole cloth, is to protect officers from having to pay monetary damages for actions undertaken while carrying out duties related to their job. But the result has been an almost complete shield from liability.

“The Supreme Court has really undercut the deterrent value of constitutional rights in preventing police abuses by making it extremely hard to hold officers accountable,” Scott Michelman, legal director for the ACLU of the District of Columbia, said.

Many of the court’s assumptions about qualified immunity are false. In particular, there is no evidence for the court’s fear that officers will be held personally liable. In actuality, it’s taxpayers who pay excessive force settlements through municipal budgets. Municipalities paid settlements in 99% excessive force cases, according to a study by UCLA law professor Joanna Schwartz. New York City taxpayers paid $5.9 million to settle the excessive force complaint resulting from Garner’s death.

Perhaps the most absurd problem with qualified immunity comes from the Supreme Court’s unanimous 2009 decision in Pearson v. Callahan. That decision held that courts can choose to look at whether an officer’s actions are protected by qualified immunity before addressing whether the underlying actions were themselves constitutional.

“The effect of that rule is to enable courts to grant immunity for the same kind of conduct without ever establishing constitutional law for future cases,” Michelman said.

This means that a victim alleging police abuse must show that courts ruled in previous cases considering similar facts that police were not covered by qualified immunity. If the abuse had never been considered by a court then the victim is out of luck. The Catch-22 absurdity of this protection is perfectly illustrated in a short video made by TikToker Karan Menon.

This video is not an exaggeration. Take the case of Baxter v. Bracey.

Alexander Baxter, a homeless Black man, brought an excessive force complaint against the Nashville, Tennessee, police after he was mauled by a police dog. The police had pursued Baxter under suspicion of burglary with the help of a police dog. Baxter surrendered by sitting down and putting his hands in the air, but despite seeing this surrender one officer released the dog’s collar. The dog bit Baxter in the underarm causing a severe wound that required his emergency hospitalization.

Even though the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals had previously ruled that the use of a dog to subdue an already surrendered fugitive suspect at night was excessive force, the court granted qualified immunity protection in this case. The one reason that the court offered why the prior precedent did not apply to Baxter’s case: Baxter surrendered while seated, the prior victim was lying down. The Supreme Court declined to take up the case on June 15.

The broad grant of qualified immunity by the court, particularly in cases involving the use of deadly force, provides officers a sense that they are above the law.

This is evident in rulings like Scott v. Harris where the court ruled that the police can use deadly force to ram the car of a suspect fleeing a speeding ticket into a ravine even though they could have simply stopped chasing. Then there is Mullenix v. Luna, where the court ruled that an officer had immunity from damages even when they shot and killed a fleeing suspect against direct orders from superiors when a less lethal measure was already planned. Or Kissela v. Hughes, when the court ruled that an officer was immune after shooting a suspect wielding a knife even when other officers on the scene felt that verbal, nonlethal options had not been exhausted.

In each of the case, the court granted immunity for the most lethal action when alternatives were not only available, but in some cases requested or ordered by other officers.

This, “sends an alarming signal to law enforcement officers and the public,” Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote in her dissent in Kissela v. Hughes. “It tells officers that they can shoot first and think later, and it tells the public that palpably unreasonable conduct will go unpunished.”

Exiting The Broken Regime

The Supreme Court has shown little evidence that it is willing to review its decisions that have built the legal structure of America’s broken policing system. Qualified immunity is the lone area where Justices Sotomayor, Ruth Bader Ginsberg and Clarence Thomas have voiced an openness to reviewing the court’s precedents. But Sotomayor may be the only justice willing to reconsider the “super powers” the court has granted to police.

“Between the super conservative justices and the more moderate ones I can’t see this court cutting back on police power,” Butler said.

Congress or state governments may pass laws that override court decisions. For example, some states already have stricter use of force standards than those approved by the Supreme Court. Colorado enacted legislation to end qualified immunity protection for police on June 19.

House Democrats introduced the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act that would roll back qualified immunity protections and change a host of ways police can interact with the public.

One key piece of the bill would change the use of deadly force standard to require police to avoid deadly force unless it is the only alternative. This means officers would have to exhaust all other alternatives before using deadly force.

“To a lot of people it sounds like common sense, but it’s not the law now,” Butler said.

This new standard probably would have prevented Atlanta police officers from shooting and killing Rayshard Brooks. It also would overturn the standard in Scott v. Harris that said police could kill a fleeing suspect to stop the danger created by the high speed pursuit instead of simply stopping the pursuit.

But what Congress, state legislatures and governors and courts cannot do is address the underlying issue at the heart of the broken policing system: the reason it was created in the first place.

“When we ask how things got so bad, I think understanding the position of white anxiety about Black men is the answer,” Butler said.

If the U.S. entered “a new regime” with Terry, it did so due to white fears of a Black planet, according to Butler’s analysis. Exiting the regime not only requires legislation and policy, but a political will to change the way white America sees Black America.

Calling all HuffPost superfans!

Sign up for membership to become a founding member and help shape HuffPost’s next chapter

[ad_2]

Source link