[ad_1]

“Mrs. Hitchcock has been steadily at work for thirty-six years, whenever called upon to supply my numerous demands,” famed scientist Edward Hitchcock wrote in the preface of one of his memoirs, recognizing the labor of his wife, Orra White Hitchcock.

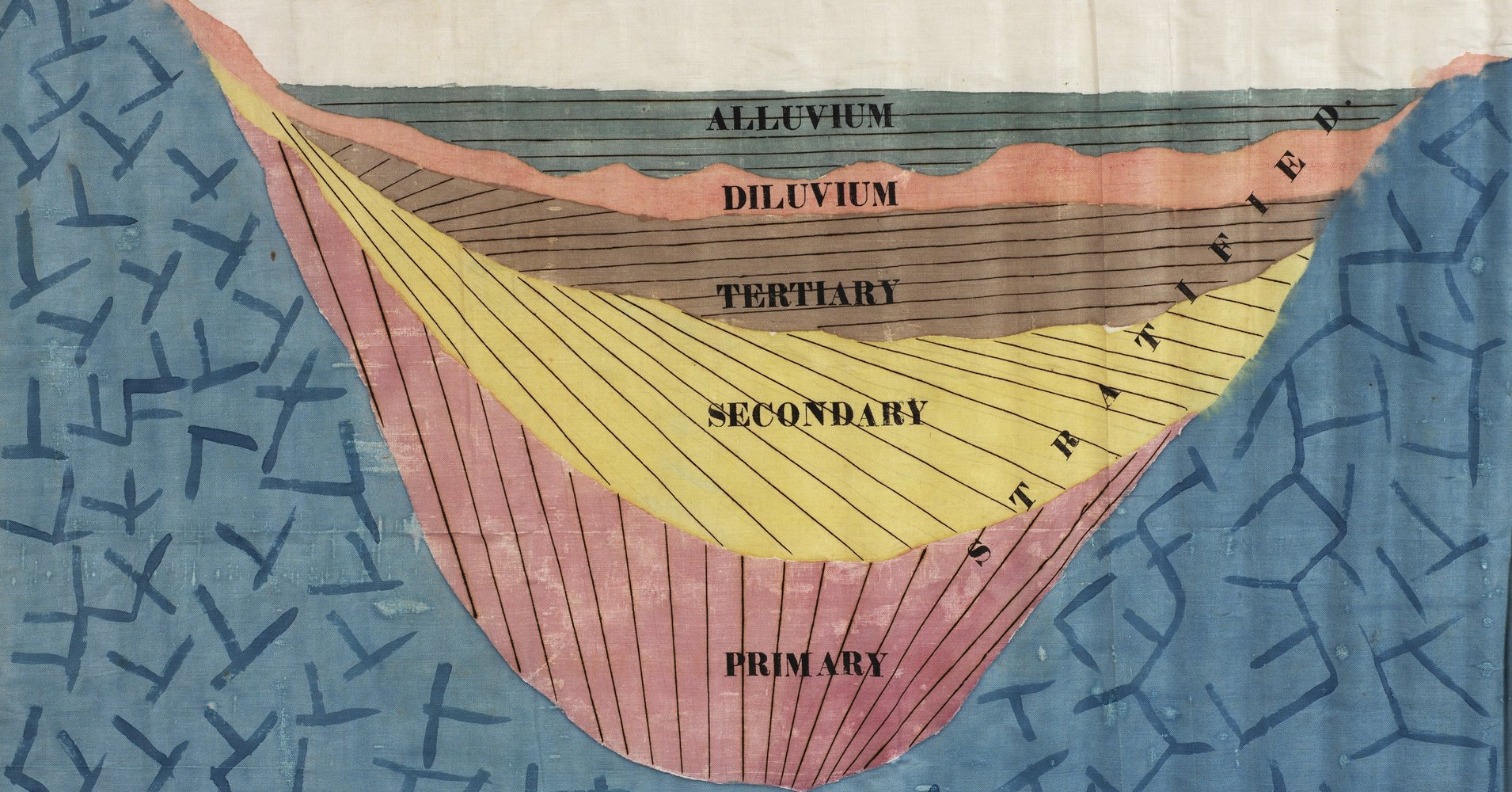

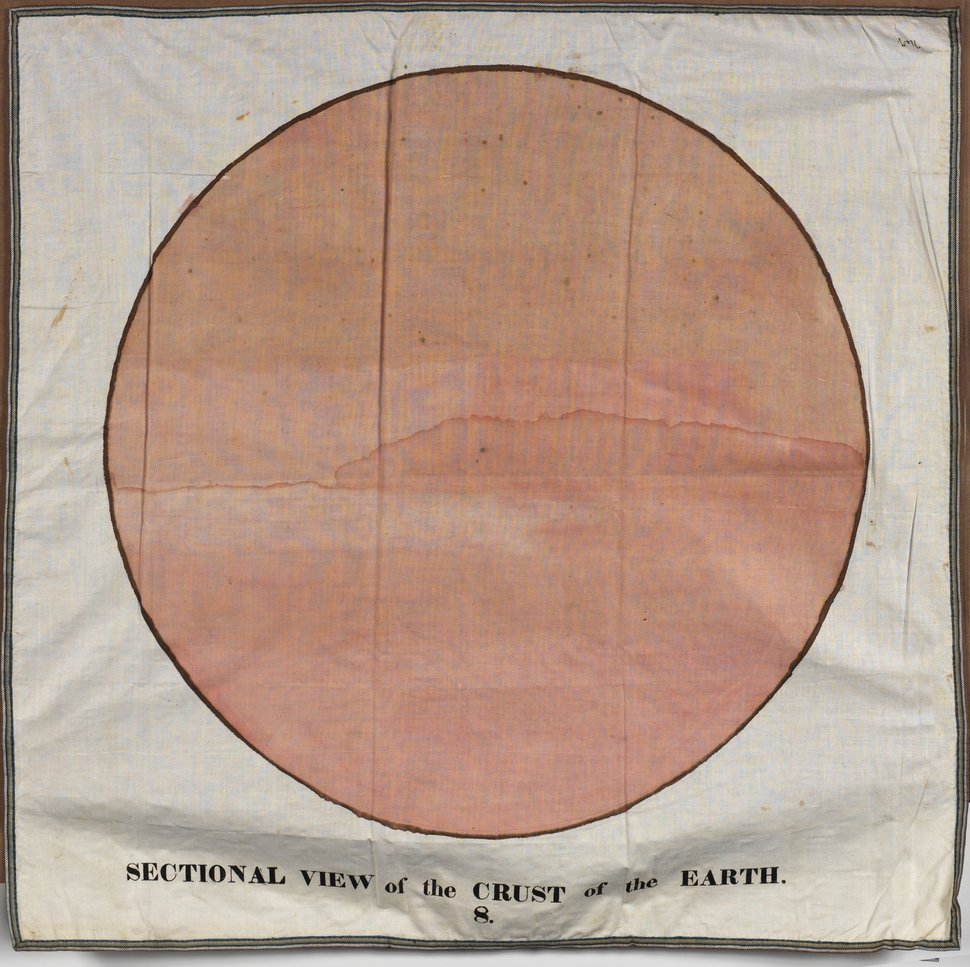

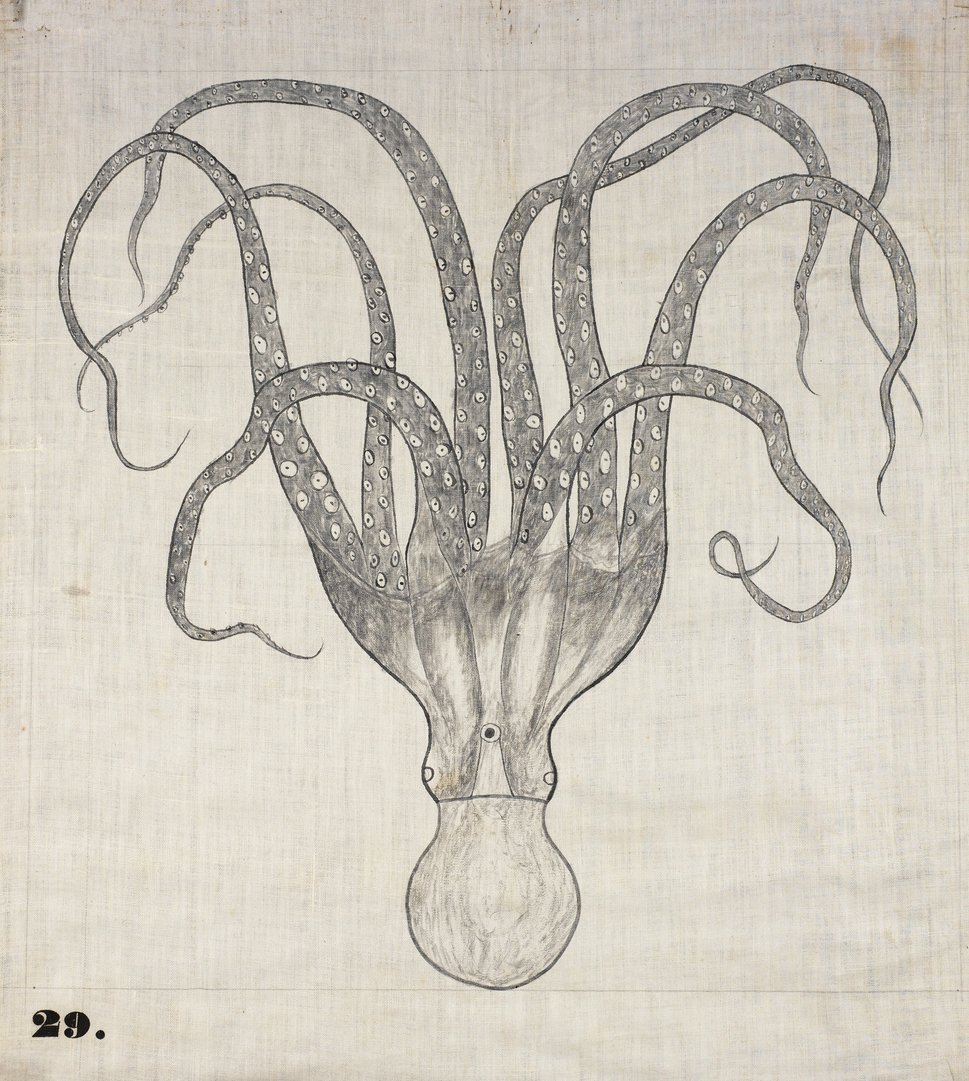

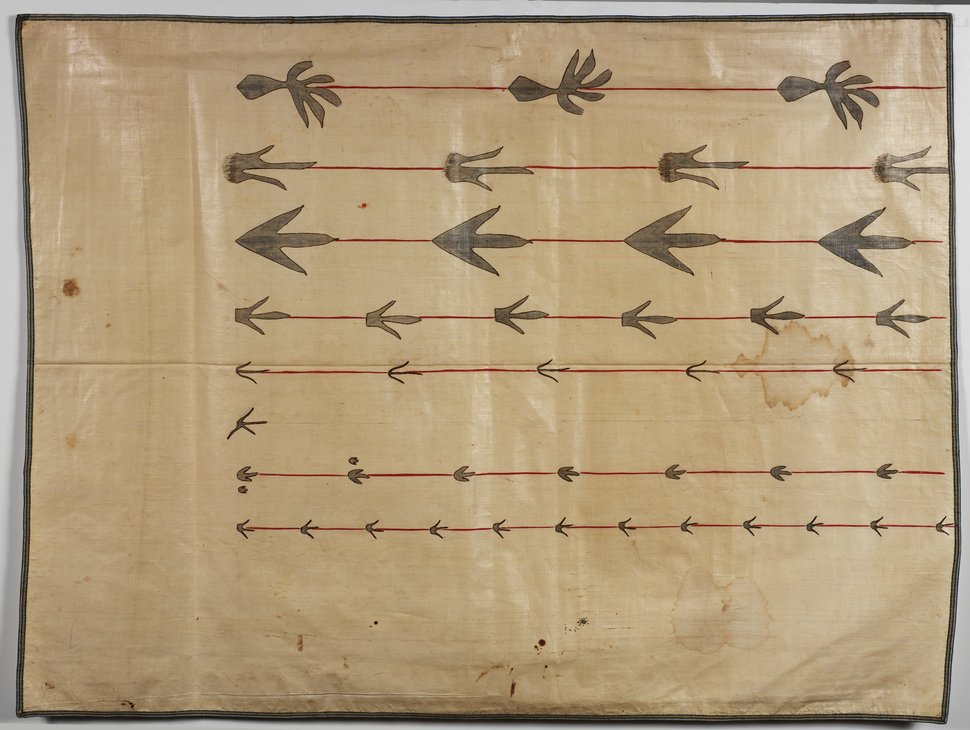

It was a funny way of saying that, for over three decades, Orra had been providing the distinctly abstract illustrations that accompanied the American scientist’s geological findings in the mid-1800s. She drew the earth’s crust as a soft orb of salmon pink, fossil footprints as a chic wallpaper design, an octopus as an oddly sensual configuration of dots and swirls. Like educational posters on acid, they were used in Edward’s lectures at Amherst College, where he was a professor and, later, the school’s third president.

“And that too without the slightest pecuniary compensation, or the hope of artistic reputation,” Edward continued. “For so large and coarse have been most of the drawings that she never felt flattered to have others told she was the author of them.”

Orra never even signed them.

In the tribute, Orra’s lack of self-promotion is framed as modesty, her renouncement of payment is cast as true devotion to her craft, and her lack of professional ambition reads as honorable. Edward’s speech, though probably well-intentioned and maybe even uniquely gracious for a powerful man of his time, hints at how women in the workplace have historically been rewarded for dreaming small.

Amherst College Archives & Special Collections

Nearly 200 years after their creation, Orra’s pioneering materials are considered valuable art objects. Today, the cotton canvases hang in the American Folk Art Museum, in an exhibition dedicated entirely to her: “Charting the Divine Plan: The Art of Orra White Hitchcock (1796–1863).” The show recognizes her as one of the earliest female scientific illustrators. On the evening of its opening, clusters of well-dressed New Yorkers swarmed the “large and coarse” works, whispering in hushed awe at how prescient, how mesmerizing and ahead of their time, they seem.

Stacy Hollander, who curated the Folk Art Museum exhibition, first attributed a trove of uncanny (and unsigned) maps to Orra in the late 1990s. That’s when she came across Edward’s memoir, in which he thanked his wife for the “many thousand square feet of surface” she created, illustrating “principles of botany, geology, zoology, and anatomy.”

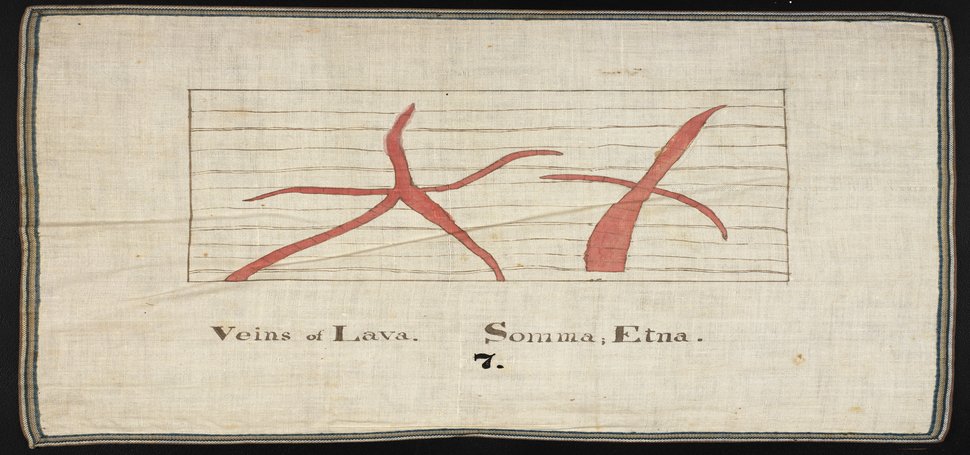

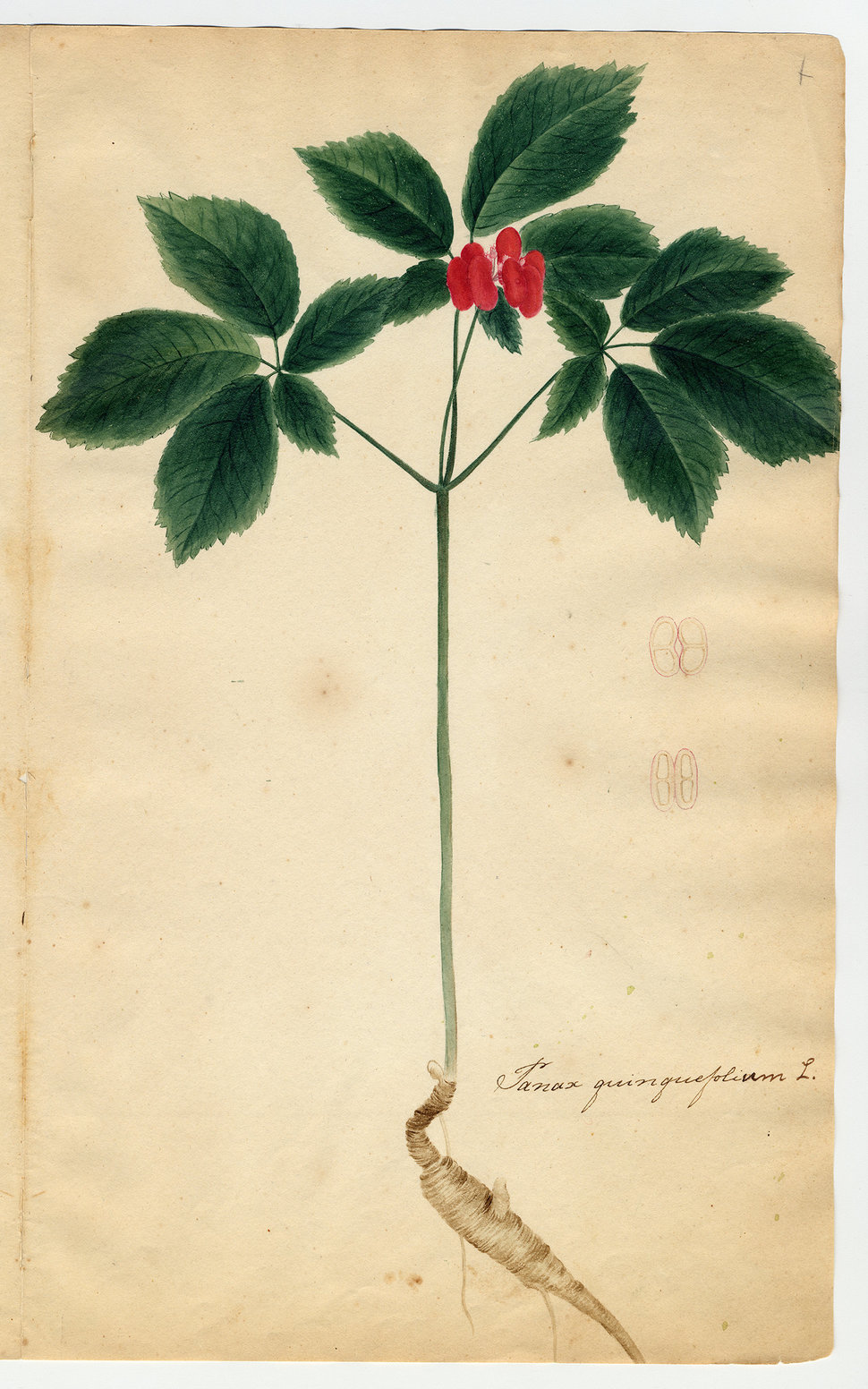

As Hollander quickly learned, Orra’s geological charts were not just routine visualizations of her husband’s research. Rather, they’re poetic abstractions of our world’s texture and guts, executed in a psychedelic palette and imbued with an avant-garde energy all their own. Orra devoted herself to visualizing mushrooms, flowers, fossils and dirt with an air of fantasy that lands somewhere between the fictional lands of visionary artist Joseph Yoakum and Dr. Seuss. A work titled “Sectional View of the Crust of the Earth” feels almost ironic in its starkness (it’s simply a pink circle), like it’s making a joke about the impossible tasks all maps take on. Another depicting “veins of lava” feels like it was ripped from the oeuvre of Louise Bourgeois, with its ability to look botanical and bloody all at once.

Their creation demanded scientific mastery and imagination in equal and abundant measure.

Amherst College Archives Special Collections

Thanks in part to Hollander, Orra is now regarded as one of the first documented female scientific illustrators; her work came alive in classrooms, libraries and laboratories, where it helped bring clarity and excitement to university students. She followed in the footsteps of German-born illustrator Maria Sibylla Merian, whose 17th-century depictions of butterflies and insects transformed the dominant understanding of metamorphosis. Orra’s contemporaries included British mycologist and illustrator Anna Maria Hussey, and Hussey’s sister Frances Reed.

Hollander discovered Orra in ’97, when a board member gifted the museum a “mourning watercolor” with Orra White’s name on the back (along with South Hadley, the location of her Massachusetts school), memorializing three of her deceased siblings. Turns out, the painting was made in 1810 when Orra was only 14. At a young age, she possessed an arresting ability to depict hard-to-grasp subjects.

Hollander, taken by the piece, did some light internet sleuthing. She learned that Orra married Edward Hitchcock, a name far more well-documented in the annals of history. In the archives of Amherst, she managed to dig up Orra’s elementary school mathematics ledgers and penmanship practice notebooks. She found love poems written to Orra by her betrothed. She found her prolific illustrations, spread out over decades.

Before long, Hollander realized she was looking at the work of a prodigy. At 14, Orra was calculating complex logarithms to determine syzygies, the alignment of the earth, moon and sun, used to predict eclipses.

Hollander eventually pieced together Hitchcock’s entire, striking biography. Born to a wealthy farmer and his wife in South Amherst in 1796, Orra was afforded every educational opportunity available to her, a rarity for young women in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. At 17 years old, she became a teacher at Deerfield Academy, where she fell in love with Edward Hitchcock, then the academy’s principal. They wed and went on to have eight children, two of whom died extremely young.

Amherst College Archives Special Collections

Along with her artistic and intellectual pursuits, Orra assumed the responsibilities expected of women at the time ― she took in boarders at her home, ran the farm, tended to the care and education of her children, and hosted religious meetings and soirees.

Orra described Edward as a challenging partner at times, suffering from melancholia and hypochondria that resulted from physical ailments he experienced when he was a kid. “He really tested her but he adored her,” Hollander said. “He sent her love letters and poems from the moment they met each other.” In one note from Edward to Orra, featured in the exhibition, they forge plans to ditch their respective plans to meet up for secret “all night” conversations.

The two were creative collaborators as well as romantic partners, known to go on extensive foraging trips in Massachusetts cataloging the flowers and mushrooms they found along the way. Orra drew each unique specimen’s every defining feature, employing a poetic sensibility that translated her husband’s lengthy findings into coherent and gripping visual forms. Although Edward, who lectured on invertebrate fossils and dinosaur footprints long before the word dinosaur was coined, remained the better-known name of the two, “Orra was pretty widely recognized by students and by his own peers as well,” Hollander said.

“More than one person commented that Edward might not have achieved what he did without her. They were a match made in heaven.”

Amherst College Archives Special Collections

Orra died in 1863 at the age of 67; her husband passed away the next year. Today, when I look at Orra’s intricate line drawings of squat fungi and elegant asters, her dramatic depictions of cephalopods, and most of all her geological classroom charts, I think about all the brilliant, creative teachers I had growing up, so many of them women.

There was Ramona Otto, whose classroom was adorned with sculptures she created from treasures found at flea markets. And Leanne Statland Ellis, who read to students aloud from a book she wrote herself about the adventures of people who lived in the clouds. And all the teachers whose classrooms are lined with diagrams, charts, maps and visualizations. What would those images look like on museum walls?

Orra White Hitchcock is an anomaly. A child prodigy, a woman whose intelligence was nurtured and encouraged, whose partner respected her intellect and gave credit where credit was due. And yet it’s very possible that her name would have remain relatively unknown had Hollander skipped over that 1810 watercolor. One could easily imagine a future in which Orra’s charts were never discovered, attributed, researched or displayed. We likely still live in a future where similar artists, many of whom are women, slip under the radar in part due to their own learned humility.

She didn’t sign most of her adult creations, but thankfully, 14-year-old Orra took credit for her work.

Amherst College Archives & Special Collections

[ad_2]

Source link