[ad_1]

Matt Tyrnauer was at Gore Vidal’s home in the Hollywood Hills a few years before his death when Vidal suddenly proclaimed that he wanted to see someone named Scotty.

“I said to him, ‘Who is Scotty?’” Tyrnauer told me. “And he said, ‘Scotty was my pimp.’”

Tyrnauer, a longtime writer for Vanity Fair who has directed multiple movies, said he asked Vidal to elaborate. Vidal started to describe a gas station on Hollywood Boulevard when Tyrnauer realized he had heard about Scotty before ― and about the gas station.

“Wait a minute, this is the gas station that was a brothel?” he remembers asking Vidal.

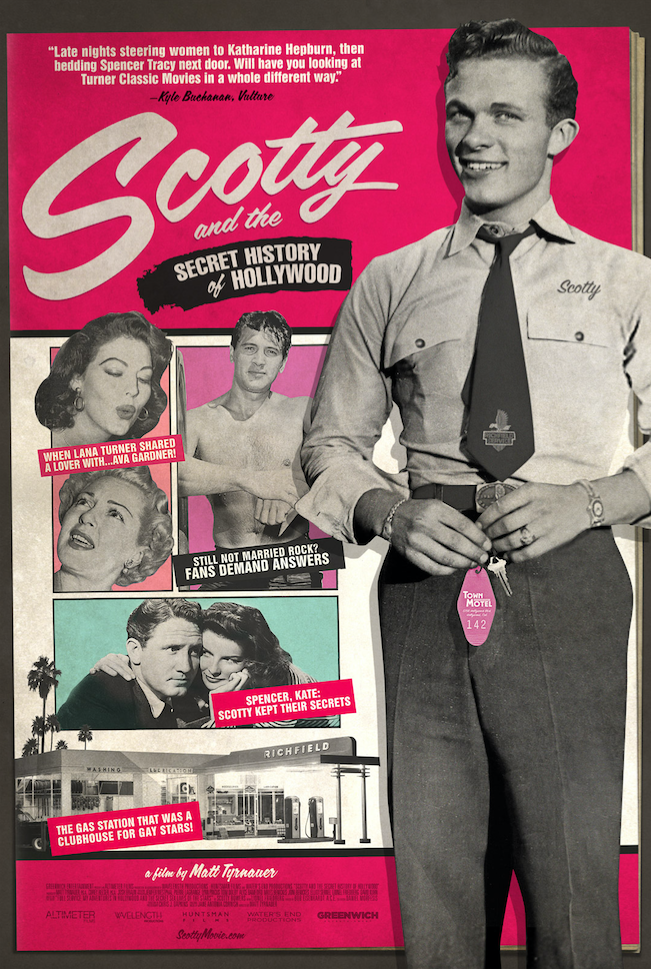

GREENWICH ENTERTAINMENT

Scotty, whose full name is Scotty Bowers, a former Marine, earned the title “Pimp to the Stars” in the years after World War II, when he ran a sex operation out of a trailer behind the gas station. The trailer came to serve as an escape for gay and bisexual members of Hollywood during an especially homophobic period in their industry.

“If you were gay or bisexual and a prominent person in Hollywood in the period after the Second World War, you were prohibited from living an authentic life in public or, in many cases, in private, because there were so many hazards,” Tyrnauer said.

Throughout his career, the eccentric Bowers, now 95, provided services to the likes of Cary Grant, Cole Porter and Katharine Hepburn, he says, accruing a covert reputation in Hollywood and out as an unprejudiced, sex-positive procurer. He developed friendships with cultural giants like sex researcher Alfred Kinsey and Vidal, who eventually introduced Bowers to Tyrnauer.

The result of that meeting is “Scotty and the Secret History of Hollywood,” an unabashedly salacious documentary that hit theaters this month. In Bowers’ life story, Tyrnauer found a way to extoll a less straightwashed, sub rosa version of the golden era of Hollywood. Though most of Bower’s alleged clients are dead now and thus incapable of verifying or denying his accounts, Tyrnauer believes Bowers’ alternative tales are valuable ones, which bite back against the prudish, heterosexual narrative of midcentury LA.

Last week I spoke with Tyrnauer about making the film, getting to know Bowers and the titillating side of Hollywood that has remained closeted for so long. That conversation, reproduced below, has been edited and condensed for clarity.

This movie focuses on a time in Hollywood when it was more acceptable to be adulterous than gay, there were morals clauses [that made it a firable offense to be gay] and vice squads and magazines outing people. Then in walks this guy Scotty Bowers. Someone in the film says they were just waiting for someone like him to come along. So who was Bowers? And what service, exactly, was he providing to these people?

Scotty Bowers was a very handsome Marine who came out of the South Pacific in World War II, ended up in Los Angeles at the age of, I think, 22 and quickly found two kinds of work.

One was as a gas station attendant at Richfield Oil station at the intersection of Hollywood Boulevard and Van Ness. The other type of work Scotty did was provide sexual services to members of the elite cast of Hollywood.

He’s sometimes referred to as the “Pimp to the Stars,” although I think “pimp” is a harsh term that leads to automatically pejorative thoughts. Scotty really is a much more positive figure who allowed stars ― who were really the victims of restrictions imposed on them by the studios through morals clauses ― to lead authentic lives.

The studios themselves were self-policing and through the morals clauses had a tight grip on the movie stars. Then there was the vice squad run by the Los Angeles Police Department, which was tantamount to a sexual Gestapo, persecuting people who had anything other than heteronormative relationships and often colluding with the press to frame, extort and humiliate people who were just trying to live authentic lives.

What drew you to Bowers’ story?

I saw an opportunity to make a movie about the alternate history of Hollywood or, in fact, show the alternate history of Hollywood through a single protagonist who is still alive at 95. The fact that he was sort of the mayor of the covert sexual world of this very significant city makes him an extremely important protagonist for a film that wants to fill in the blanks and show, before it’s too late, a full picture of exactly what was going down in the golden period of the studio system.

GREENWICH ENTERTAINMENT

You follow him after he has written this book about his life. He says at one point he wrote the book to show that some of these people in Hollywood are just people ― fleshed-out, fully formed people, like anyone else. Did you make this film for a similar reason?

I viewed the film from the outset as a political film. Hollywood and Los Angeles aren’t just big famous cities or famous places. Starting 100 years ago, the studio system created the American myth, and that myth then spread all around the world. And at a certain point, the narrative that Hollywood insisted on producing was one that portrayed white, heterosexual lifestyles as the only moral option for living a decent life. This was very purposeful and, in the end, quite corrupt.

That there was more than meets than eye to the company town that produced these enduring myths is, I think, important.

Bowers’ book names names, and he goes into detail in your film about the particular sexual preferences of some of these celebrities. It had me thinking a lot about the politics of outing the dead. It’s addressed in your film a little bit. There’s a clip of women on “The View” discussing it, and some people ask him about it at some of his book signings. Was that something you grappled with at all?

I think Scotty puts it best in the film when someone confronts him and says ― I’m paraphrasing ― “Didn’t you feel guilty about writing a tell-all book? What if someone in your book’s grandkids finds out?” Scotty responds, quite sensibly, “What’s wrong with being gay?”

These are public figures, and some of them are extremely important public figures. They hold a unique place in the old psyche because of the power of Hollywood. If we’re going to have many biographies of Cary Grant, to have them all be straightwashed accounts of who Cary Grant was is not only dishonest but perhaps harmful. I would pose this question: Is it not relevant to know that Michelangelo was gay? If you’re doing a biography of Michelangelo that portrays him as a heterosexual male, I think that that’s doing a disservice to the reader, to say the least. So why wouldn’t we want to know the full spectrum of historic figures’ private lives when we’re so granularly studying these people almost 100 years after the prime of their fame?

Bowers also seems to have put a lot of time and thought into that as well. He said it might have been a secret to people outside Hollywood. But inside their social circles, many people knew these people were not wholly heterosexual, even if they were not publicly out.

He says also very wisely, “I wanted to show people that people are still people,” and that’s his way of making the point as well. Why put a movie star such as Cary Grant or Katharine Hepburn on some sanitized pedestal and insist on worshipping an artificial image that was burnished by a publicity machine? If you care so much to know the details of the lives of Katharine Hepburn and Cary Grant and Tyrone Power and all the other great figures of the period, why not know the full spectrum? Why insist on continuing to perpetrate a straightwashed version of their biographies? It just doesn’t make any sense to me, and I think it’s really a form of homophobia.

The footage inside his homes is very interesting. It becomes obvious that Bowers is something of a hoarder. What did you take away from that?

Well, he’s a hoarder, to say the least, and I’m a neat freak, so to be filming in a hoarder’s world for two years was interesting for me. It had its disturbing elements ― because I find hoarding disturbing, as do a lot of people ― but also had its advantages as a filmmaker because he didn’t throw anything out. We were able to excavate in some of his storage units some very compelling proof of his existence of as the male madam of the gas station, including scores of photos from the period that he hadn’t seen since the time they were taken.

As to what Scotty’s hoarding means, I present it unvarnished in the film. I leave it to the interpretation of the viewers and the psychiatric community to say precisely what it symbolizes. If I had to guess, and this is an unqualified guess, I think it points to a lot of loss in his personal life, because he did have that. Starting with World War II and the death of his brother, also a Marine, on down to the death of his daughter from a botched abortion in the late ’60s, there’s been a lot of painful blows.

It seems that on top of the personal tragedies he has faced, his time in the war really affected him for the rest of his life.

He’s really the all-American boy of the 20th century. He’s just much more candid than most of them, so he’s telling you the parts that many left out.

Kinsey and Bowers were friends, right? That, to me, was one of the most interesting characters to enter the film. Do you know anything about that friendship and what drew Kinsey to Bowers?

Yes, I do. I called the Kinsey Institute at [Indiana University in] Bloomington, and I spoke to one of the researchers there, who said he was very familiar with Scotty Bowers because there was a very big file on Scotty in Dr. Kinsey’s personal archive, including correspondence, postcards and letters written from Scotty to Dr. Kinsey. Scotty was a major source and resource for Kinsey ― source because he was interviewed by Kinsey for the data pool for his groundbreaking book [Sexual Behavior in the Human Male], which really changed the whole equation for sex and sexuality worldwide when it was published.

Kinsey sought Scotty out as a subject because he attempted to find certain sexual unicorns who could show him spectrums of sexuality that were never discussed and inaccessible to medical research up until that point. Scotty was one of those people, according to him. Kinsey wanted to know about Scotty’s activities, and Scotty being an open book ― at least in that period to a doctor who was willing to work to him confidentially ― told him everything, then helped him with this research by introducing him to worlds that Kinsey would not normally have access to, which were the hidden worlds of same-sexuality in Los Angeles at the time.

This gets to one of the major points in the movie, which is that the gay world in Hollywood had to be a secret because the consequences of being open were just too dire. You would be fired if you worked for a studio, or you could be arrested by the Los Angeles Police Department’s vice squad, or you could be simply humiliated or ostracized. It was not an easy time to be gay, especially in a city that had so many spotlights on its population and its environment. So Scotty introduced Kinsey to Rock Hudson and many other people in the city who were keen to meet the person who showed them perhaps for the first time that they were not degenerates or freaks or sexual outlaws but that they were normal human beings.

GREENWICH ENTERTAINMENT

Someone in the film says he thought Bowers was almost something of an urban legend for a while, but you obviously got significant access to him. Was he open to the documentary from the start? What was your relationship like with him?

The person who said that was William Mann, who is a very esteemed historian and Hollywood biographer. He was saying that sources told him for years that you have to talk to Scotty Bowers to confirm a lot of the information about the unknown or previously untold sexualities of key figures in the movie colony, and he jokes, “I began to think Scotty was an urban legend because I heard about him so much but I could never figure out how to find him.”

So I figured out how to find him through Gore Vidal, who introduced me to him. I had heard about him for years from sources in Hollywood and subjects of articles I had written about. The person to tell me about Scotty was, in fact, Merv Griffin, who mentioned the gas station. He didn’t mention Scotty, but he said there was a gas station on Hollywood Boulevard where you used to go to get into trouble, which was his euphemism for same-sex activity, I gather.

At the time, I was a full-time writer, editor-at-large for Vanity Fair magazine, and I began to make notes about this mysterious gas station that seemed to be a kind of significant untold story about the secret world of gay Hollywood. One day, I was sitting with Gore Vidal in his living room in the Hollywood Hills, and he blurts out of nowhere, “I want to see Scotty.” I said to him, “Who is Scotty?” And he said, “Scotty was my pimp,” and I said, “Well, tell me more.”

He said, “We had a gas station on Hollywood Boulevard,” and then immediately I bolted up in my chair and said, “Wait a minute, this is the gas station that was a brothel?” And he said, “Yes, I met him there in 1948,” which Scotty confirmed for me. He had reconnected with Scotty in the last five years of his life. Next time I went to Gore’s house, Scotty was there. That’s how I met him and because of the endorsement of Vidal, I really had Scotty’s trust from the outset.

It’s amazing what a Gore Vidal endorsement will do for you, you know?

Well, in that area it was the ultimate. I’ll give you a line that I haven’t given to anyone else: Friends of Gore speculated to me when Scotty’s book was published that this was Gore’s ultimate “Fuck you” to Hollywood.

Really? Why do you think that was?

Because Vidal was a very brave, out gay man, and he, I think, knew all the secrets of Hollywood — or most of them. He thought that it was ridiculous that they were so protected and very hypocritical, and I think he knew who to go to to blow the lid off. He indeed did help Scotty get the book published just a few years before [Vidal’s] death.

This movie left me thinking about the politics of being gay in Hollywood today. By comparison, where do you think Hollywood is in 2018?

Like any big city, things are much better. There have been extraordinary strides in the abilities or people with sexual identities other than hetero to thrive and find acceptance. But there’s still a ways to go. In the movie business in particular, there’s a conundrum, which is that it’s thought that the success of many films depends on the sexual fantasies of the viewer, and it’s presumed that frequently those fantasies are heterosexual, and I suppose the fear is that if the leading man or leading woman is known to the viewer to be interested in the same sex in their offscreen life, the scenario onscreen might not work for them.

I’m guessing that’s why there aren’t a lot of out leading men and leading women, but that’s just a guess on my part, and I’m sure as the culture progresses and the embracing of looser sexual identities and sexual fluidity continues among younger, wiser generations that those individuals will be making these decisions one day and won’t be as strict in their tribal beliefs about cookie-cutter sexual identities.

[ad_2]

Source link