[ad_1]

Ever since Jeanine Cummins’ novel “American Dirt” was released on Jan. 21, much of the media has described the ensuing controversy in terms of nationality and ethnicity.

This question continues to come up: Is a non-Mexican allowed to write about Mexico?

Accusations have flown back and forth on social media: cultural appropriation versus “cancel culture,” whitewashing versus censorship, exploitation versus stay-in-your-lane allegations. Cummins couched the debate in racial terms in her now-famous “someone slightly browner than me” comment from the book’s epilogue.

Flatiron Books, the publisher of “American Dirt,” this focus in its official statement to the Los Angeles Times: “The concerns that have been raised, including the question of who gets to tell which stories, are valid ones.” When the publisher recently canceled the entire book tour, it cited “concerns about safety,” characterizing opposition to the book as “vitriolic.”

In all the uproar, I have yet to read any personal threats against Cummins that might merit a “safety concern.” Most important, nearly all of the major critics of the novel have clearly stated that race and nationality are not the main issues. The focus on ethnicity is misleading, presenting Latino and Latina opponents of the novel as “hot-headed sore losers,” resentful that somebody else got the million-dollar deal.

David Bowles, one of the first authors to pan the novel, reiterated during an NPR interview that his critique “doesn’t mean that we think that authors shouldn’t be allowed to write outside of their identity.” Esmeralda Bermudez writes in the Los Angeles Times, “I don’t take issue with an outsider coming into my community to write about us. But ‘American Dirt’ so completely misrepresents the immigrant experience that it must be called out.”

To be sure, recent history is full of gross misrepresentations of Mexico. However, certain non-Mexican authors have proved that just the opposite is possible. In fact, some have been in a unique position to collaborate with Mexican voices.

John Kenneth Turner wrote extensively about Mexico a century before Cummins began “American Dirt.” Like Cummins, he was an Anglo author from the United States. Like Cummins, he wrote about poverty and human suffering. And yet he is widely revered in Mexico to this day.

What is the difference between them?

Fighting Modern Slavery

Turner, born in 1879, began writing about corrupt businessmen and politicians when he was a teenager. By 1908, he had moved to Los Angeles with his wife, and the couple began connecting with exiled Mexican citizens who opposed the dictator, Porfirio Díaz. After spending years in Mexico researching the root causes of discontent, Turner published a series of articles in The American Magazine, which were later published jointly under the title “Barbarous Mexico.”

Though Turner came to Mexico as a foreigner, he quickly proved his qualifications to write about the country. He was intimately familiar with Mexico’s history and spoke fluent Spanish, interviewing indigenous laborers, urban workers and revolutionaries. These people described the horrors they had experienced firsthand: slavery in the Yucatán Peninsula, the genocide of the Yaqui people from the north, the widespread system of debt slavery and “contract slavery” throughout central and southern Mexico.

Despite the Trumpian sound of the title “Barbarous Mexico,” Turner’s aim was not to depict Mexico as a perennially backward nation. Rather, the barbarism he described was a central, intrinsic component of the U.S. economy. Mexico’s northern neighbor needed the Díaz dictatorship — and all of its brutal tools of oppression — to maintain business as usual.

“When I say the United States,” Turner clarified, “I do not mean a few minor and irresponsible American officials […] I mean the federal government and the interests that control the federal government.”

While Turner described the heartless cruelty of landowners and slave traders in Mexico, he never lost sight of the main culprit. He accused the United States of transforming Mexico “into a slave colony of the United States” and proceeded to name the U.S. companies that controlled large sectors of the Mexican economy: Standard Oil, the American Sugar Trust, Inter-Continental Rubber, Wells Fargo, the Southern Pacific Railroad and many others.

These Yankee interests shaped U.S. policies toward refugees from the south. The description of the border in Chapter 14 rings eerily familiar to this day:

“Constantly during the past three years the American government, through its own Secret Service, its Department of Justice, its Immigration officials, its border rangers, has maintained in the border states a reign of terror for Mexicans, in which it has lent itself unreservedly to the extermination of political refugees of Mexico who have sought safety.”

Infiltrating The Plantation

In addition to his intimate connection with the most marginalized and oppressed people in Mexico, Turner used his position of privilege, and his own nationality, to further his research.

In the first chapter of “Barbarous Mexico,” he explained how he was able to cozy up to the owners of the henequen plantations in the Yucatán Peninsula, collecting information on their labor practices. Turner posed as a wealthy American investor and was quickly invited to dine in the lavish mansions of the elites. After gaining their trust, he finally began to broach a taboo subject: slavery. Mexico had officially abolished it in 1810, and the landowners continued to deny its existence. Eventually, however, they confided in Turner.

“The planters do not call their chattels slaves. They call them ‘people,’ or ‘laborers,’ especially when speaking to strangers,” Turner wrote. “But, when speaking confidentially, they have said to me: ‘Yes, they are slaves.’”

These landowners frankly discussed the price of a human being with Turner, suggesting that he take advantage of the low price at the time, as “One year ago, the price of each man was $1,000.”

Turner’s aim was not to profit from sensationalistic, leering depictions of human suffering. His writing had an immediate purpose: to build support for the Mexican resistance. He had developed personal relationships with Mexican intellectuals, labor unions, civil society organizations and opposition groups that would form the vanguard of the Mexican Revolution.

Turner’s entire book was a call to action for U.S. readers, urging them to stand in solidarity with their Mexican comrades, to oppose both the Díaz dictatorship as well as the U.S. interests that kept him in power. Turner did not write about “victims” but rather active agents who fought to break their own chains.

Since the inception of the Mexican Revolution, it was built as a binational movement. The Flores Magón brothers published political texts and organized with the Mexican Liberal Party while in exile in Southern California. To overthrow the Díaz dictatorship, they sought the collaboration of U.S. radicals: anarchists, socialists and the “Wobblies” of the Industrial Workers of the World. Turner’s writings played a key role in rallying the support of U.S. progressives.

To this day, “México Bárbaro” is required reading in classrooms all across Mexico. Students read Turner’s accounts of slavery, exploitation and poverty, and are moved to tears. The book still inspires national pride, social consciousness and outrage against all forms of injustice, past and present.

All this, from a non-Mexican author.

As Partners And Equals

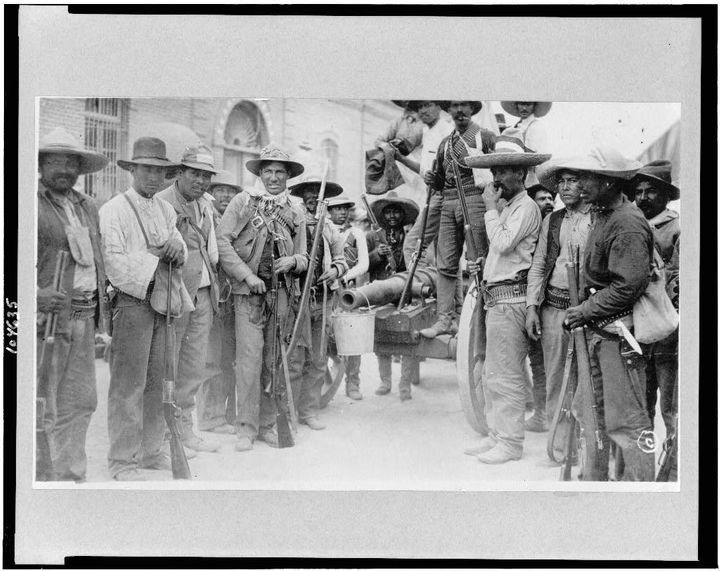

Turner was not the only U.S. author to stand in solidarity with Mexico’s revolutionaries. John Reed reported on the revolution for the Metropolitan Magazine in 1913, spending four months with Pancho Villa’s troops as they prepared to march on the capital. His book of collected writings, “Insurgent Mexico,” is a mainstay of literature from that period.

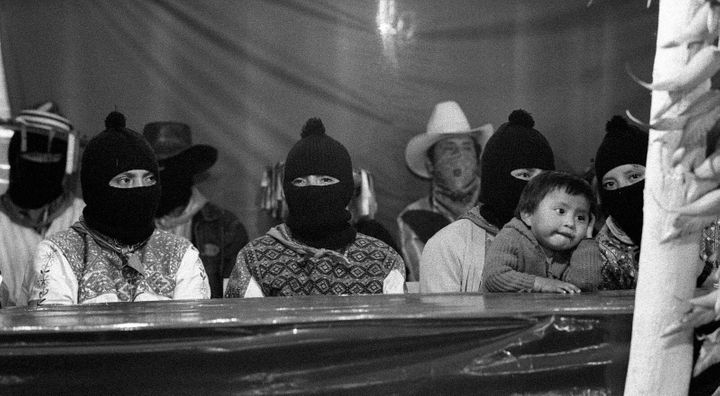

Many contemporary non-Mexican authors have followed the same example. John Ross lived in Mexico since the 1950s, covering Mexican politics and current events, until his death in 2011. His book “The Annexation of Mexico” should be required reading for any foreigner interested in Mexico. His in-depth coverage of the indigenous Zapatista uprising in Chiapas inspired Blanche Petrich, of the Mexican newspaper La Jornada, to describe him as a “new John Reed covering a new Mexican revolution.”

Likewise, Jon Lee Anderson has long written about resistance movements throughout Latin America. His fascinating book “Guerrillas” was just released in Spanish by the publisher Sexto Piso. David Bacon has covered labor issues in Mexico for decades, interviewing maquiladora factory workers, labor union activists and migrant farmworkers. He has described the devastating effects of the North American Free Trade Agreement on the Mexican countryside and calls for transnational solidarity between unions in the U.S. and Mexico. In addition to their impeccable research, Anderson and Bacon both are fluent in Spanish.

Stephanie Elizondo Griest has been writing about the border region with pathos and courage throughout the past decade. Regarding her book, “Mexican Enough: My Life Between the Borderlines,” Chicano author and professor Alex Espinoza comments: “I must admit that I came to the book a bit skeptical, since it was about a journalist venturing into Mexico to do some root-searching. I couldn’t have been more wrong about that book. About Griest’s skill and talents as a tenacious, honest journalist willingly putting herself in harm’s way, willing to expose herself to scrutiny and criticism, in order to tell the kinds of stories that matter to our community.”

The past century has seen many more foreign authors who have written about Mexico with nuance, respect and accuracy: the engaging novels of Malcolm Lowry, Paul Theroux and B. Traven; the hard-hitting journalism and political analysis of Aviva Chomsky, John Womack and Danielle Mitterrand. The list goes on.

These authors are a collective example for any American who wishes to respectfully write about Mexico — indeed, about any other country — as an outsider. Their works avoid exoticizing or “othering” Mexico with the leering gaze of “trauma porn,” to quote Bowles’ review of “American Dirt.” In the end, writers who honestly examine Latin America reach the same conclusions as Turner. At the end of “Barbarous Mexico,” his ethical convictions are stronger than any blind nationalism:

“If it is to the interests of the United States that a nation should be crucified as Mexico is being crucified, then I am opposed to the interests of the United States.”

He warns of a possible U.S. invasion of Mexico and ends his book with a political “altar call” for readers:

“That will be the time for decent Americans to make their voices heard. They will […] demand that, for all time, our government cease putting the machinery of state at the disposal of the despot to help him crush the movement for the abolition of slavery in Mexico.”

Turner and his successors invite us to move beyond the false dichotomy in the right and left wings of U.S. politics, the dangerous myth that migrants and Mexico must be viewed either with disdain or sympathy, with hatred or pity. Through their informed, humble and intelligent writing, these authors show us a courageous third option.

Calling all HuffPost superfans!

Sign up for membership to become a founding member and help shape HuffPost’s next chapter

[ad_2]

Source link