[ad_1]

On the surface, “The Old Man & the Gun” is the story of Forrest Tucker, a serial bank robber and fugitive who flitted in and out of jail from age 15 until his death at 83.

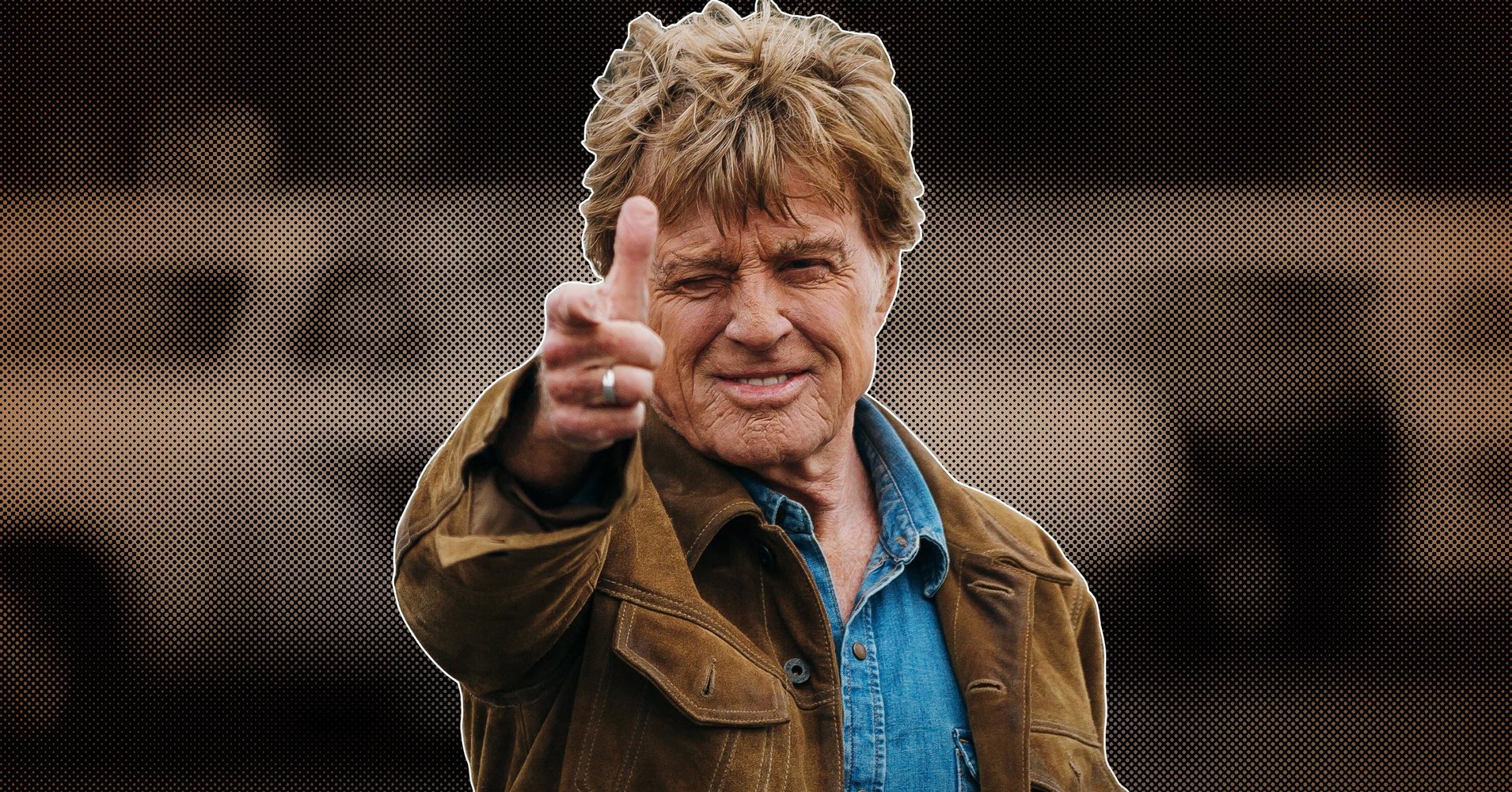

But for most intents and purposes, “The Old Man & the Gun” is actually the story of Robert Redford, an actor who built a career by playing charismatic outlaws just like Tucker. Heralding his possible retirement, the film doubles as commentary on Redford’s legacy, awash with nods to the six-decade tenure that made him one of Hollywood’s primo leading men.

“A lot of times, when you’re telling a true story or you’re trying to tell someone’s life story, you think, ‘What actor would be right for this part? Who could pay this character?’” director David Lowery said. “And in this case, it was more, ‘How can we make this true story work for Robert Redford?’ That was my North Star in telling it: How can I take the facts, which are too good to be true and are numerous, and shape them around the last great movie star that we have in this era in cinema history?”

It was Redford who first thought Tucker’s lawless enterprise had the right intrigue for the big screen. A fan of Lowery’s breakout film, the atmospheric crime romance “Ain’t Them Bodies Saints,” Redford approached him with the 2003 New Yorker profile chronicling this blue-eyed smoothie who “had also become perhaps the greatest escape artist of his generation, a human contortionist who had broken out of nearly every prison he was confined in.”

Lowery then spent a few years developing the project ― in the interim, he and Redford also made Disney’s splendid live-action “Pete’s Dragon” ― and along the way realized that “The Old Man & the Gun” should be far more than a familiar tale about a charming antihero.

Lowery’s initial script hewed to the facts: Tucker, a thief and bank robber who spearheaded the so-called Over-the-Hill Gang, fled prison “18 times successfully and 12 times unsuccessfully,” as he told The New Yorker reporter who visited him at a Texas penitentiary not long before his death in 2004. Suspected in at least 60 robberies spanning a one-year trek across Oklahoma and Texas, Tucker was a hard-edged crook who picked up John Dillinger’s torch with a calm demeanor, piquant grin and surprising saxophone skills. Wearing an apparent hearing aid that was actually a police scanner, his transgressions took him to Massachusetts and Florida and made him the subject of a California manhunt.

But Lowery retrofitted Tucker’s saga to benefit Redford’s charisma, adding a screwball tempo and folksy score to the proceedings. It became the story of an “iconoclast” who captured the nation’s attention with a wink and a smile, just like Redford did in the films that made him famous (“The Chase,” “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid,” “The Sting”). If you can’t help but fall in love with the Tucker of “The Old Man & the Gun,” that’s the point. The protagonist’s crimes, as one character observes, aren’t so much about “making a living” as they are experiencing thrills wherever they can be found. In keeping, the role requires someone audiences won’t hesitate to embrace even when Tucker 0makes bank tellers cry and lies to his new love interest (Sissy Spacek).

The 37-year-old director, who also made last year’s hypnotic “A Ghost Story,” didn’t know it might be Redford’s swan song when he was writing the script. Should the actor’s threat of withdrawal hold steady, “The Old Man & the Gun” is an ideal sendoff, leaving us with a tour of his career that any performer would envy.

Here’s what Lowery had to say about seven Redfordian allusions in his movie, which opened in theaters on Friday.

Fox Searchlight

1. The opening frame

Before we even glimpse Redford, “The Old Man & the Gun” fires off a subtle ode to one of his most celebrated movies, the 1969 western “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid.”

Audiences had swooned over Redford two years earlier in the romantic comedy “Barefoot in the Park,” co-starring Jane Fonda, but it was his turn as the taciturn outlaw known as the Sundance Kid that enshrined the actor in pop culture. The character said little, yet Redford’s dapper face spoke volumes ― something only a first-rate movie star can pull off.

“Butch Cassidy” opens with the announcement “Most of what follows is true.” In tribute, “The Old Man & the Gun” begins with an azure title card and yellow text that reads “This story, also, is mostly true.”

“It’s a direct reference to ‘Butch and Sundance,’” Lowery said.

2. The “weird” forgotten parts of Redford’s early work

Given the popularity of Redford’s movies throughout the late ’60s and ’70s, it’s easy to forget how idiosyncratic they were. A key example: “Downhill Racer,” a 1969 drama that was a key reference point for Lowery. Redford played a skier whose eyes on the championship prize underscored his lonely disposition and narcissistic drive.

“One of the things I loved about that movie is how rough around the edges he let himself get,” Lowery said. “I wanted to make sure we don’t sand down Forrest Tucker so much that he was simply a charming guy. I wanted him to have some more unlikable qualities, so the moment where he lies to Sissy Spacek reminded me of ‘Downhill Racer’ — just letting him be an unsavory guy, an unsavory masculine character.”

Tucker is far more endearing than Redford’s “Racer” introvert, but we cheer on both because we want them to succeed in spite of their vices. In another feat of movie-star magic, they feel like humans instead of shadowy archetypes. The same can be said for “Butch Cassidy,” “The Hot Rock,” “The Sting” and even “The Great Gatsby” ― films that paved the way for the out-and-out heroism on display in “Three Days of the Condor,” “All the President’s Men” and “The Natural.”

“I did want to make a film that had a kinship to the movies that made him a movie star,” Lowery said. “And the movies that made him a movie star were movies in which he was an outlaw. He’s always had this iconoclastic quality, and I think that’s what people fell in love with, in addition to the heartthrob qualities that later led to his romantic films.”

Lowery studied Redford’s catalog, looking for the je ne sais quoi that transformed him into a matinee idol. Indeed, Redford helped introduce a new breed of male movie star who expanded on Cary Grant’s debonair ease and James Stewart’s everyman relatability to include a renegade flair.

“He was really leaning into the New Hollywood approach of the late ’60s and early ’70s, where the movies were taking on strange countercultural shapes,” Lowery said. “Here’s a guy with the most classical movie-star good looks making really weird movies, and that was something that I keyed into with all those early films. […] ‘Butch and Sundance’ is a very strange movie. We remember these iconic moments, but the movie around it had a very strange shape to it ― the fact that it’s all about the aftermath, on the one hand, and is also really unwieldy in its narrative. It doesn’t follow the traditional beats that we think about it following. We remember the freeze frame, we remember the cliff jump, we remember so much other stuff in there that wasn’t traditional and still is not traditional.”

That squares with Tucker’s legacy, too. He wanted his story consecrated in the American consciousness, which to him meant being the subject of a movie like “Bonnie & Clyde” or “Escape from Alcatraz.” It’s not a huge leap to assume Tucker sought a certain cinematic grandeur for his own crime sprees. Hence why Lowery “ran with the legend” instead of marrying himself to factual details. “Forrest Tucker wanted to be Robert Redford being an outlaw,” he said.

Fox Searchlight

3. Portraits of the artist as a young man

The narrative grist of “The Old Man & the Gun” finds a weathered detective named John Hunt (Casey Affleck) attempting to locate Tucker and understand his motivations, giving it what Lowery calls “the ‘Citizen Kane’ path of trying to uncover who this guy really was.” In his research, John encounters a collection of mug shots and other photographs that amount to a flip book chronicling Tucker’s life. We watch as the images float by, one after the next, Ticker aging in quick succession.

But what we’re really seeing, of course, is Redford aging, that beloved blond hair and ice-blue irises holding strong no matter how many wrinkles grace his forehead. The sequence begins with an elementary-school yearbook photo and quickly cycles through various publicity images, including one from “The Sting” that’s photoshopped to look like a mustachioed mug shot. Redford matures in what feels like real time, and the movie insists we swoon at the nostalgia it evokes.

4. The prison break from “The Chase”

Another stirring montage in “Old Man” recounts the numerous times Tucker cultivated clever ways to abscond from jail, including fashioning a kayak so he could break out of San Quentin State Prison (which, by the way, really happened). These escapes were in Lowery’s script from the get-go, using lookalikes to portray the younger Tucker. But he also had the brilliant idea to include ’60s-era Redford. “I wanted there to be a very palpable sense of us seeing the history transpire onscreen before us, and to do that we needed to see his face,” Lowery said.

When they were making “Ain’t Them Bodies Saints,” Affleck had recommended to Lowery “The Chase,” a proto-“Bonnie & Clyde” that opens with Redford making a prison break. He plays a wrongly convicted Texan who returns to his small hometown after fleeing the law. With the actor’s permission, Lowery added to the montage in “Old Man” a brief clip from “The Chase” in which Redford climbs a tree and peers into the expanse, his eyes gleaming with newfound liberation.

“We’ve spent 90 minutes in very close proximity to his face, so we’re always aware of Robert Redford the movie star,” Lowery said. “But to all of a sudden see the breadth of Robert Redford the movie star in that moment is very moving.”

Sunset Boulevard via Getty Images

5. The horse he rode out on

Redford’s career can be measured by the horses that carted him from one frontier to the next. An equestrian apostle at a young age, the actor’s skills were put to use in “Butch Cassidy,” “The Electric Horseman” and “The Horse Whisperer.” In 1975, he trekked on horseback from Canada to Mexico for a National Geographic project that resulted in the book The Outlaw Trail: A Journey Through Time.

During a meditative moment in “The Old Man & the Gun,” Redford hops atop a horse to evade the police cars trailing him. It’s Tucker sailing off into the sunset, leaving behind a life lived on his own terms.

6. A finger swipe worthy of “The Sting”

As “The Old Man & the Gun” turns into a cat-and-mouse game putting Tucker against Hunt, the pair form an unlikely parallel. Both are emboldened by their mutual quests. Tucker teases the police about their ignorance, and the detective finally lands a project that isn’t the same old dispiriting doldrums. Despite conflicting interests, they become spiritual analogs.

When Tucker has finally been caught and sentenced to more time behind bars, Hunt visits him at the hospital where he is handcuffed to a gurney. After a compassionate goodbye, Affleck lifts his pointer finger, swipes the right side of his nose and saunters out of the room. The gesture is a savvy nod to “The Sting,” in which the con men portrayed by Redford and Paul Newman exchange that signal as a go-ahead.

The nose move is one of Lowery’s more direct Redfordian allusions, though it was actually Affleck’s suggestion to include it. Lowery had considered ending “The Old Man & the Gun” on a freeze frame that emulated “Butch Cassidy,” but he eventually decided that would be “taking it a little too far.”

Fox Searchlight

7. An eternal youthfulness

Redford remains overwhelmingly handsome to this day, in part because his toothy grin and windswept hair haven’t changed one lick. Nonetheless, he brings a distinct insouciance to “Old Man” that evaded recent films like “Truth,” “A Walk in the Woods” and “All Is Lost.” Most notably, Tucker’s nascent romance with the widow played by Spacek feels like a schoolyard courtship. They are tentative around each other, slowly revealing truths (and half-truths, in Tucker’s case) as if untutored in dating practices.

That sense of discovery was present on the set, too. On their first day of shooting together, Lowery had to remind Spacek that she was conversing with Forrest Tucker, not Robert Redford. In other words, she needed to play a little hard to get.

Later, during a date at a diner, the camera pans out from Redford and Spacek to canvass the room, revealing tables of teenagers fraternizing with friends or experiencing fresh love. “The direction I gave to Bob and Sissy in this film was to play their relationship as if they were 16-year-olds going out on their first couple of dates. […] It just feels very romantic in that high school sort of way. That shot was designed to dolly in to a close-up of Sissy, and as we were shooting it, I was looking at what was going on around and just asked the camera operator to pan away from them so that they became yet another couple out on a first date. It was such a beautiful moment to see their youthful spirits surrounded by literal youth. It really was one of my favorite moments on set, just realizing they were there in that moment with all these other characters who are having equally momentous moments in their young lives.”

[ad_2]

Source link