[ad_1]

In a signature scene from “Grey Gardens,” Edith “Little Edie” Bouvier Beale parades down a staircase in the decaying East Hampton, New York, mansion she shares with her eccentric mother, “Big Edie,” aunt to former first lady Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis. It’s the fall of 1973, and Little Edie hoists a small American flag in her outstretched hand. As her upper body enters the frame, clad in a black leotard and red-trimmed headscarf, she waltzes straight toward the camera crew stationed across the room.

Grinning, Edie twirls the flag like a dance partner, spinning it to and fro, filled with a joie de vivre unlikely for someone who has fallen from high-society beneficiary to highly scrutinized recluse.

Little Edie’s performance is the sort of display that’s inescapable today. Our televisions and social media feeds are crawling with people eager to find the nearest camera, desperate to cash in on the proverbial 15 minutes they thought might never come. The Beale women were America’s reality stars before the term “reality star” existed. They satisfied the same archetypes ― catty, attention-starved, delusional, staunch ― that have come to define that genre of contemporary entertainment.

As the ultimate mark of a reality pro, Little Edie loved “Grey Gardens,” the 1975 documentary that portrayed her and her mother as curiosities in the capitalist treasure chest that is American pop culture. Instead of seeing it as a woeful slice of opportunism, she presumably viewed the film as we do: a delicious tribute to a woman who remained unflinching despite her troubled existence ― an unfiltered product belonging to an era that never was the Camelot it sought to be.

“That Summer,” a new documentary that acts as a de facto prequel to “Grey Gardens,” has a scene that’s equally evocative. It’s June 1972, and Little Edie points to a shed in her overgrown yard, telling cousin Lee Radziwill (Onassis’ sister) that she claims the building as her own. “There’s a song called ‘My Adobe Hacienda,’ and this is it,” Edie says in her posh lilt. And then, as if suddenly remembering there’s a camera observing her, she whips around and launches into the opening verse, scurrying toward the lens as if it’s her stage.

The same proud grin that accompanied that American flag spreads across her face.

Little Edie’s routine encapsulates how divine it is to spend another precious 80 minutes with the Beale duo, who became a societal fixation in the 1970s after a New York magazine cover story and the Maysles brothers’ immortal “Grey Gardens” brought their tale of squandered wealth out of the tabloids and into the national limelight.

In the intervening years, their saga has been mythologized and dramatized umpteen times over: a Beale-themed photo spread captured for Italian Vogue in 1999, a Broadway musical in 2006, an HBO film starring Jessica Lange and Drew Barrymore in 2009, multiple impersonations on “RuPaul’s Drag Race,” a “Documentary Now!” parody featuring Bill Hader and Fred Armisen in 2015, various quips on “Gilmore Girls,” “Modern Family” and Joan Rivers’ Comedy Central roast.

Little Edie and Big Edie are caricatured enough for “That Summer” to serve as both correction and confirmation. Yes, as pop-culture emblems, they really were that kooky and fascinating; just look at Little Edie’s makeshift wardrobe or the way Big Edie hollers at Little Edie from across their unkempt manor. But as humans, they were, of course, far more complex. Their backstory includes familial acrimony and misguided decisions ― fodder that captivated the public in the days before mass-media oddities were a dime a dozen. But if their interactions in “Grey Gardens” were sometimes careless and stormy, “That Summer” is downright tender by comparison.

“Oddly enough, I think the Beales’ situation is much about how it is to be a woman, the limits of how you could behave and be eccentric as a woman,” Göran Hugo Olsson, the Swedish director of “That Summer,” said by phone last week. “They are protected by their cloths and their privilege, up to a certain extent. And then when they cross that limit and be too eccentric for the community or the society, society hits back at them.”

Olsson’s theory holds up. In the 1920s, having married a well-heeled lawyer named Phelan Beale and become the matron of the home known as Grey Gardens, Big Edie mounted amateur singing pursuits and formed opinions that her image-obsessed Bouvier clan considered subversive. She was steadily ostracized from the family and written out of her rich father’s will. Post-divorce, she retreated into the mansion she retained, more or less trapping her daughter inside ― a decision that would alter the younger Edie’s life forever. By the time the Maysles came knocking, the $65,000 trust fund they’d subsisted on since 1948 had dwindled.

Without writing off their extreme peculiarities ― Big Edie and Little Edie stopped cleaning, rarely left their property and faced constant threats from authorities ― it’s fair to suspect their bloodline prevented the Edies from becoming their own women. Both had beautiful voices that could have yielded fruitful music careers, had they been encouraged to pursue such paths. But Big Edie, an artist? The Bouviers, forever chasing straight-and-narrow affluence, wouldn’t hear of it. As she became more and more of a spectacle, her daughter’s potential became less and less abundant. You’d go mad too, stuck inside that sprawling home with a mother who insists you stay within shouting distance.

“I’ve never had privacy in my whole life,” Little Edie gripes in “That Summer” after her mother tells her she lacks the cojones to leave Grey Gardens, as she has long threatened. (“It’s boring, boring, boring here! I’ll go anywhere to be free!” she declared in the New York profile, published in 1972.)

Consider, too, a scene in which Little Edie recounts a phone conversation with Onassis. City officials had hosed down the house’s rotting walls, and Little Edie brags about ringing up her famous cousin to complain. It’s the perfect snapshot of the “Grey Gardens” lore: the oversimplified image of the upscale White House alumna who left her relatives in squalor (Onassis actually saved them from eviction), pitted against the oversimplified image of the onetime country-club patrician now too hapless to help herself (after her mother’s death in ’77, Little Edie moved to New York City and later to California and Florida).

Would we be as fascinated with the Beale pair today? Presidential ties aside, I’m not so sure.

You see, “Grey Gardens” is a relic of an age before reality television, when hoarders and doomsday obsessives and Vanilla Ice going Amish weren’t primetime fodder. Vérité documentary ― a fly-on-the-wall treatment that catalogs reality without talking heads, directorial flourishes or a score ― was still a relatively new concept. We were two decades away from “The Real World,” O.J. Simpson, Lorena Bobbitt and Tonya Harding creating the perfect storm that accelerated the 24-hour news cycle. The “Survivor”–“Big Brother”–“Fear Factor” boom of the early 2000s, which gave way to tasteless curios like “Here Comes Honey Boo Boo” and “Best Funeral Ever,” makes “Grey Gardens” look like more of a human-interest oddity than a sliver of bona fide cultural intrigue.

Big Edie and Little Edie unwittingly helped to shape the reality TV model that proceeded from them. They represent the same paradigms that define today’s programming. They’re loudmouths with a tenuous claim to fame who clearly thrive on attention, even if they don’t ask for it. In 1976, The New York Times called “Grey Gardens” a “circus sideshow,” a description that also befits “The Bachelor,” “Teen Mom,” the “Real Housewives” and Kardashian franchises, “The Apprentice,” “Catfish” and so much more.

But, like “Grey Gardens,” those programs aren’t sideshows because they have nothing to offer the world; they’re sideshows because they mold their characters into one-dimensional exhibitions, delighting us with an inherent familiarity that lends itself to armchair gossip. The Edies were the original one-dimensional exhibition. When Little Edie speaks directly to the camera, it’s as if she is recording the confessionals that are now obligatory for reality series. What then seemed off-kilter can now be considered prescient.

Fast-forward a few decades, and Lee Radziwill’s daughter-in-law, the former TV journalist Carole Radziwill, is a cast member on “The Real Housewives of New York City,” a show on which another cast member, socialite Sonja Morgan, once said, “There’s nothing grey about my gardens.” The evolution comes full circle.

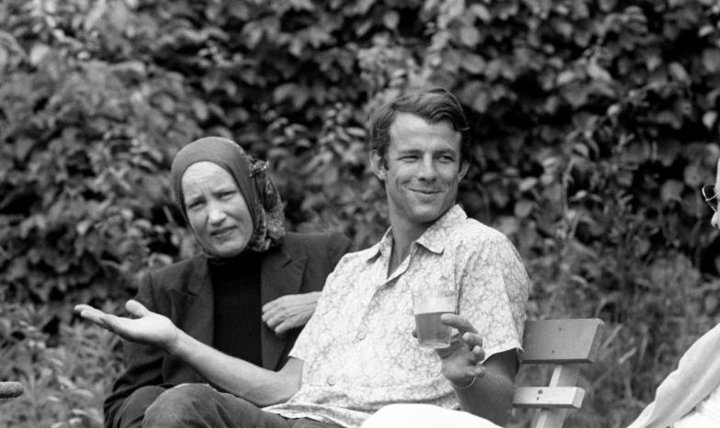

“That Summer” is compiled using footage from Lee Radziwill and then-boyfriend Peter Beard’s 1972 trip to visit her aunt and cousin in an attempt to have them narrate her childhood memories. According to the movie’s prologue, the footage has been “lost” for 40 years. What a joy to have it today, both as an archival exploration of Americana and a counterpart to the complexities often omitted in the sparseness of “Grey Gardens.”

“I never thought of the Beales as unfortunate or sad or anything except very excellent at feeling what it was like to hold on to the past,” Beard says in “That Summer.”

The film is rife with cameos from the Studio 54 staples with whom Beard and Radziwill caroused — Andy Warhol, Bianca Jagger, Mick Jagger, Truman Capote, Paul Morrissey. Amid these famous faces, another American contradiction emerges: All those artists who spent their lives courting fame are considered normal, but as for the two who chose to carry out theirs in seclusion? Well, that’s just positively insane.

“That Summer” opened in limited release May 18.

[ad_2]

Source link