[ad_1]

“You can never forget, can you, Carl Reissman?”

Those are the first words of “Master Race,” a 1955 comic by Bernie Krigstein, Al Feldstein and Jack Davis. Spoken by an omniscient narrator, the vague question drags readers into its opening panels. “Even here… in America… Ten years and thousands of miles away from your Native Germany,” it continues. “You can never forget those Bloody War Years.”

The title appears boldly atop the first page, cut in half by a miniature black swastika. Below is Carl Reissman himself, a white man in a khaki trench coat and fedora, descending into a subway station with his hands in his pockets. He buys a ticket and enters through a turnstile just in time to catch his train roaring into the station, an “onrushing steel monster.”

“Why are you frightened, Carl?” the hovering voice asks, the second question more off-putting than the first. “That was a long time ago! This is America. You’re safe now! You’re free.”

That assurance ― that the Holocaust is a horror of another time and place ― is familiar to many American Jews. In 2018, however, it’s an increasingly impotent claim. Particularly after the October massacre of 11 Jews in a Pittsburgh synagogue, which triggered a sickening sense of deja vu for so many. The Holocaust might be in the past, but its demons are far from locked there with it.

“These times are not a small bit chilling,” author and cartoonist Craig Yoe said.

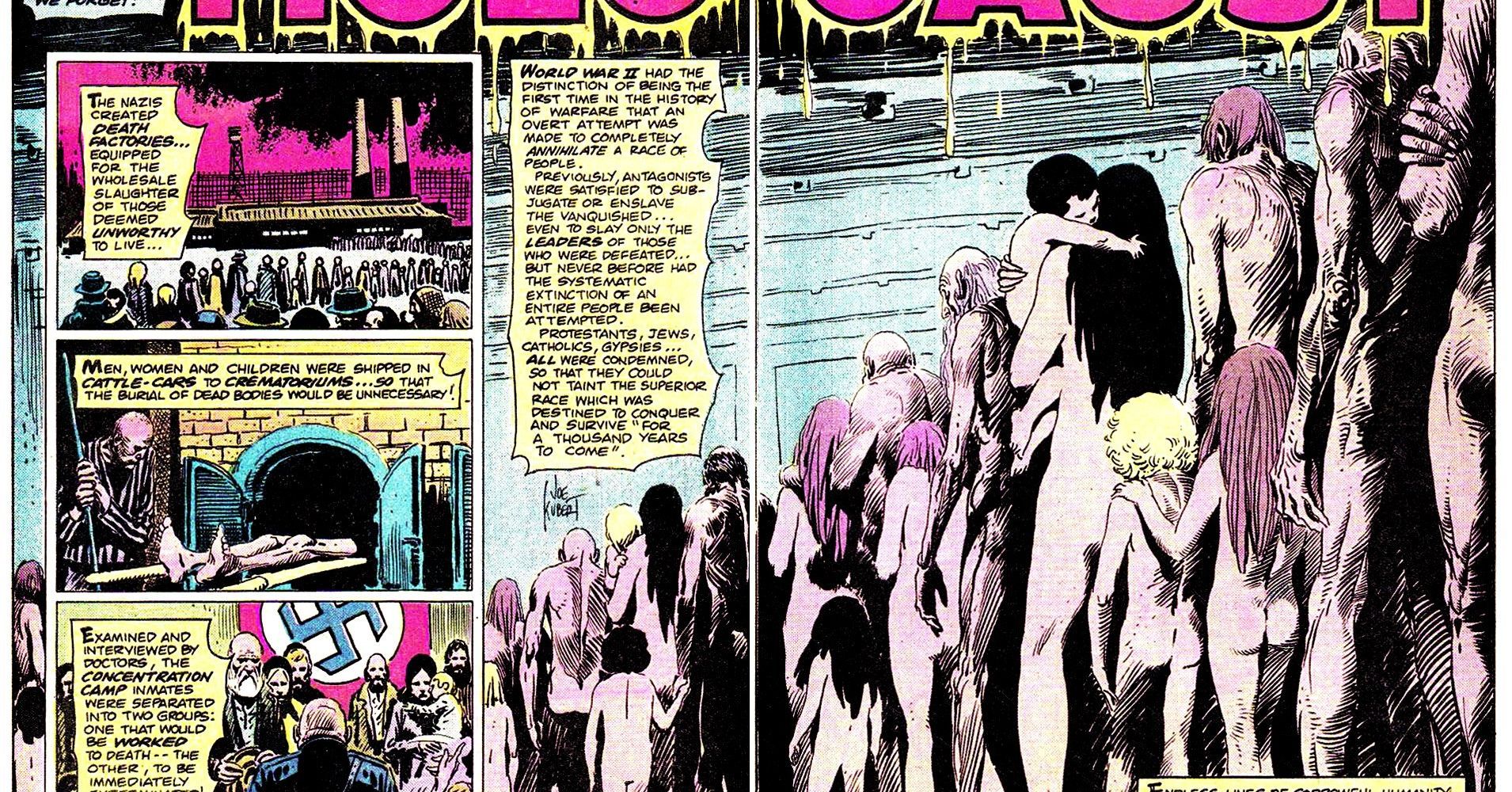

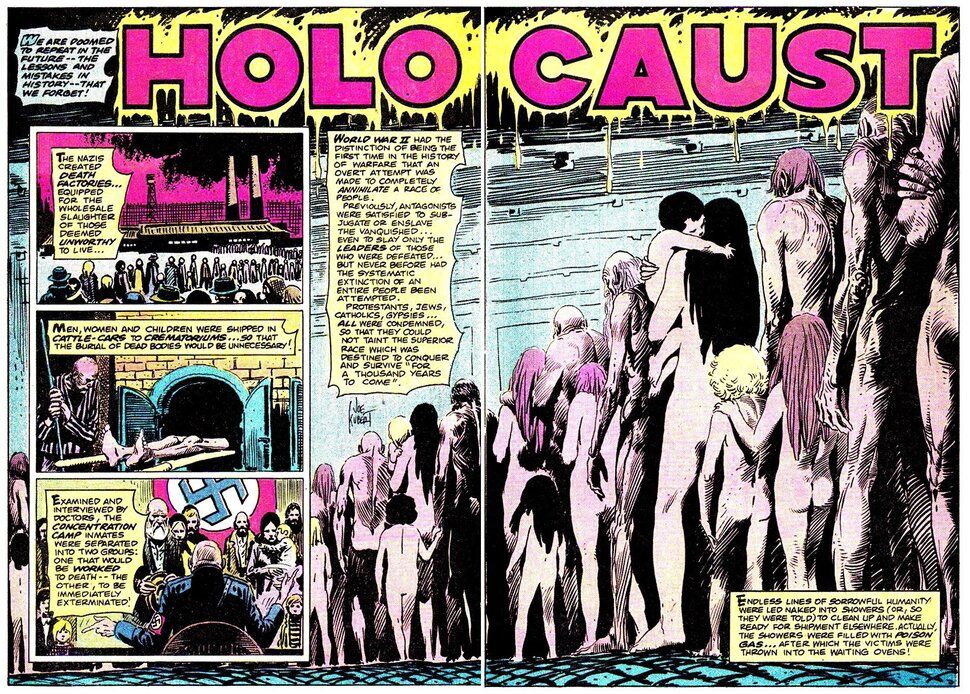

Along with Neal Adams and Rafael Medoff, Yoe is co-editor of We Spoke Out: Comics and the Holocaust, a compilation of comics made in the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s, visualizing atrocities of history through graphic panels and text bubbles. Contained within are comics that emerged years before public schools began widely teaching the events of the Holocaust, before they were immortalized in films like “Schindler’s List” and graphic novels like Art Spiegelman’s “Maus.”

“Comic book creators were really unsung pioneers in Holocaust education,” Medoff, a historian and the director of the David S. Wyman Institute for Holocaust Studies in Washington, said. “They really did speak out at a time when most other people didn’t.”

Before television, before the sprawl of the internet, comics were a medium for binging, the stuff parents worried would rot their teens’ brains and corrupt innocence. The reasons were twofold: Comics were easy to produce, printed at a breakneck pace by publishers. And the readership was there to greet them.

“Kids weren’t using their money to buy books,” Adams said. “They were buying comics.”

As a result, writers and artists from the 1950 to 1980s were given “tremendous freedom” to concoct stories as they wished, Yoe said. Overworked, underpaid and eager to churn out the next hit, creators addressed grisly topics other fields didn’t dare touch, unafraid to tell the spine-chilling tales that gripped readers.

“Comic book people are not in the business of crusading,” Neal Adams told HuffPost over the phone. “They’re in the business of telling stories and getting paid at the end of the week. Running across subject matter like this, it’s really very little more than business as usual.”

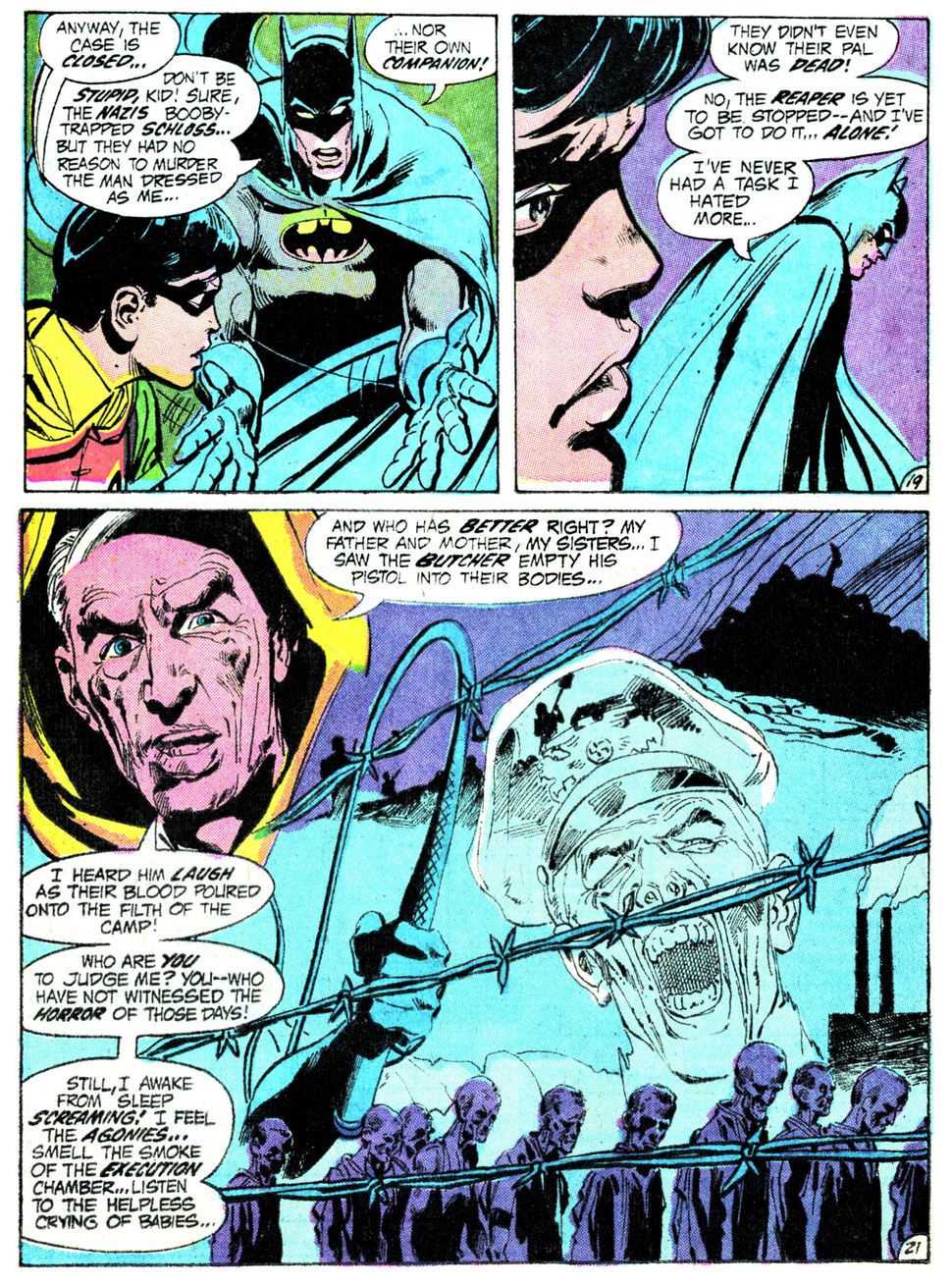

“Subject matter like this” included Hitler, the Third Reich and the 6 million Jews murdered in concentration camps. These historical atrocities became plot points in Marvel and DC comics, from Batman to X-Men to Captain Marvel. In the 1980 Captain America issue “Night of the Nazi,” the Captain’s landlady, Anna, recalls painful memories from her time in Diebenwald, where she played in the concentration camp orchestra. Some real-life camps had such compulsory ensembles, whose music would accompany prisoners’ whippings and executions.

One day, in 1980 Brooklyn, Anna runs into Dr. Klaus Mendelhaus, also known as “the Butcher of Diebenwald,” who forced her into sexual slavery. She faints from the shock. Mendelhaus kidnaps her and brings her to an abandoned church, where she learns of his intention to start a new Nazi regime. Just then, Captain America soars in with a “Kraash!” and battles the hoard of Nazis one by one.

“I can hate too,” Captain America says as he smashes a cluster of Nazis with a wooden frame. “I hate everything you stand for!” In the end, Anna and Captain America have the butcher surrounded. Anna points the gun toward her former captor as Captain America begs her not to shoot.

“Murder is the only solution left…” she says. “This butcher taught me that.” With a “blam blam” she shoots him dead.

According to Adams, these comics weren’t necessarily created with a moral imperative in mind. Yet Yoe suspects “many working-stiff artists and writers have an ingrained social conscious,” and “these comics reflect their defiant little subterfuge against evil.”

After all, Jewish people factored prominently in the nascent comic book industry. “Harry Donenfeld published Jerry Seigel and Joe Shuster’s story of a welcomed immigrant, Superman,” Yoe said. “Bob Kane co-created Batman. Stan Lee, with Jack Kirby created the X-Men.” Of the 18 stories in We Spoke Out, 11 were written by Jews.

Most of the comics featured in We Spoke Out adhere to the norms of the genre, juxtaposing superheroes in capes with SS soldiers wearing swastika armbands. Imaginary visions of Robin battling the Grim Reaper live just pages away from horrible images of mass graves and medical torture. Comic books’ typically sensational flourishes take a backseat to the very real events described because, as Adams put it, “there is little about the Holocaust you can sensationalize.”

Not every comic written about the Holocaust appropriately balanced education and entertainment, a reality the co-editors kept in mind when selecting the works for their book. “In one 1950s horror comic, the Jewish victims came back from the dead as vampires to bite Nazis,” Medoff said. “You can see why we didn’t include that one in We Spoke Out.”

The comics that made it in, however, combined history, fantasy and emotion to boil an unfathomable historical nightmare down to stories that American youth would devour. As Medoff added, “these comic book stories can be just as effective today as they were when they were first published, because the problems they’re addressing never completely go away.”

Yoe described “Master Race” as the “Mona Lisa” of comic books. It certainly catches the reader off guard when it’s revealed that the protagonist Carl ― who finally, in America, is safe and free ― was not a Jewish prisoner but a Nazi commander at the Belsen concentration camp.

“Do you remember, Carl?” the narrator continues. “Do you remember the awful smell of the gas chambers that hourly annihilated hundreds and hundreds of your countrymen? Do you remember the stinking odor of human flesh burning in the ovens… Men’s… Women’s… Children’s… People you once knew and talked to and drank beer with?…”

Beneath the text, men and women shuffle about town, separated from the camp by a yellow wall. They tuck their faces into their coats and breathe into handkerchiefs to mask the stench.

The narrator proceeds to haunt Reissman with reminders of the evils he committed. He grows more panicked upon recognizing another passenger on the train, a gaunt man in all-black. As the train grinds to a halt, the man in black catches Reissman’s gaze and screams, “It’s you!”

Reissman rushes off the train and sprints through the station, with the man in black trailing close behind. “Run… As you ran from Belsen, Carl!” the narrator howls. A train approaches. Reissman, running wildly through the platform, loses his balance and falls onto the tracks. A panel focuses on the man in black’s face as the train zooms by, crushing Reissman beneath it. A crowd gathers, but the man denies knowing Reissman at all. “He was a perfect stranger…” he says, turning his back to the reader.

This article has been updated to include “Master Race” co-author Bernie Krigstein.

REAL LIFE. REAL NEWS. REAL VOICES.

Help us tell more of the stories that matter from voices that too often remain unheard.

[ad_2]

Source link