[ad_1]

Behind every great love story is a great song. Welcome to HuffPost’s Rom-Com Week.

In June, “Hereditary” became one of the year’s signature horror hits, chronicling a grieving family whose trauma unleashes demonic frights upon their affluent existence. The two-hour film begins as a gradual shiver and ends as a steadfast nightmare. But when “Hereditary” finally fades to black, a cheery harpsichord offers a respite from the darkness. It’s the same harpsichord that, five months later, furnished the music for, of all things, the first “Toy Story 4″ teaser.

It’s reasonable to assume the newest “Toy Story” installment, which revolves around a kid-friendly road trip, couldn’t be more different from “Hereditary.” And yet they are now inexorably linked, along with a host of other movies and TV shows, by their shared use of “Both Sides Now.”

In a way, this comes as no surprise. The five-decade-old song has been popping up more and more in popular culture, its themes refracted to evoke any number of feelings across any number of genres. Even if you really don’t know life at all, you know you’ll hear “Both Sides Now” sooner rather than later. Seeing it in two polar-opposite Hollywood productions in the same calendar year feels, by now, all too expected.

A24

“Both Sides Now” has soundtracked or provided fodder for umpteen films and TV classics, starting long before 2018: two episodes of “The Wonder Years,” “Sesame Street,” “You’ve Got Mail,” “Life as a House,” “Love Actually,” the 2010 Winter Olympics opening ceremony, “Mad Men,” “Steve Jobs,” the 2017 Oscars’ “In Memoriam” segment.

Because its lyrics explore dualities ― “give and take,” “win and lose,” “up and down” ― the anthem has come to mean different things in different contexts. Universality is its appeal, and perhaps its curse: It can be melancholic or hopeful, sticky or sweet, a dreamer’s optimism or a realist’s heartache. The wistful current running beneath “Both Sides Now” italicizes a potency that now risks being overplayed.

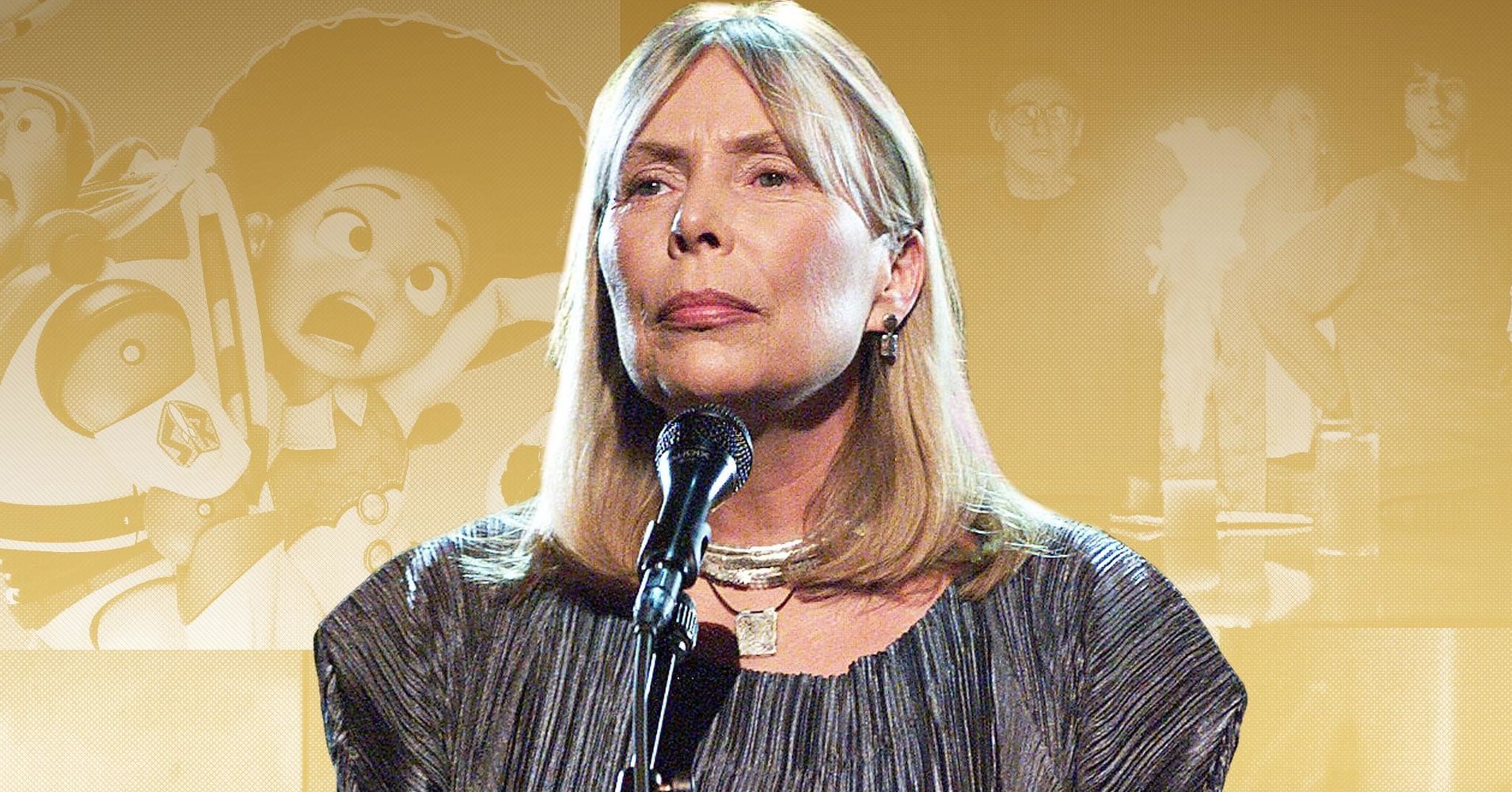

Joni Mitchell first performed “Both Sides Now,” which she wrote, as a mid-tempo guitar ballad during a 1966 concert in Philadelphia, two years before her debut album. “I was reading Saul Bellow’s Henderson the Rain King on a plane, and early in the book Henderson the Rain King is also up in a plane,” Mitchell later explained. “He’s on his way to Africa and he looks down and sees these clouds. I put down the book, looked out the window and saw clouds too, and I immediately started writing the song. I had no idea that the song would become as popular as it did.”

Henry Diltz via Getty Images

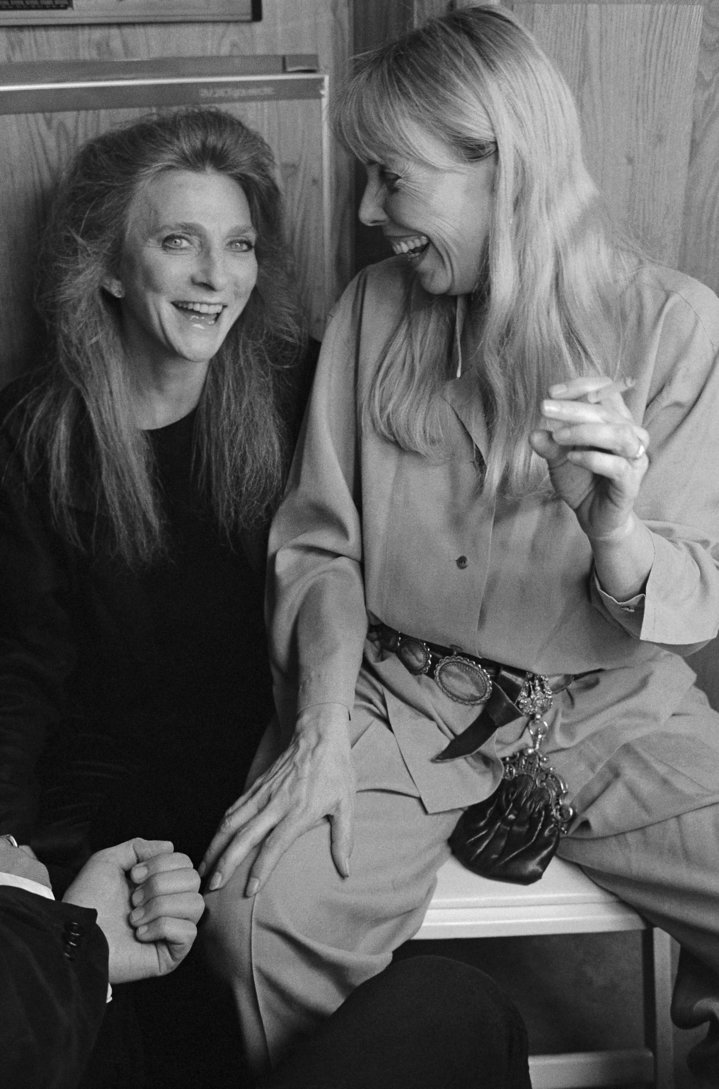

Judy Collins released a jauntier rendition in 1967 ― the one with the aforementioned harpsichord ― after meeting Mitchell through a mutual record-producer friend. Its folksy psychedelia won Collins a Grammy and remains her defining hit. Two years later, Mitchell recorded her original version, which became the closing track on her sophomore album “Clouds.”

Then, in 2000, after having been anointed one of the 20th century’s premier songwriters, Mitchell redid “Both Sides Now” with a lush orchestra. The update was part of a concept album also titled “Both Sides Now,” which documents a relationship from start to finish. This time, Mitchell’s voice was husky, weathered and filled with sorrow, telling a different story than it had in the late ’60s and further emphasizing the psalm’s malleability.

Movies and TV had already seized the song, and it would only increase from there. The pilot of “The Wonder Years” first tapped into its delicate anguish in 1988, employing Mitchell’s “Clouds” finale while the show’s hero, Kevin Arnold (Fred Savage), narrates recollections of his suburban adolescence. After positioning the series in a turbulent 1968, the year that Martin Luther King Jr. and Bobby Kennedy were assassinated, Kevin announces, “I guess it really was my last summer of pure, unadulterated childhood.”

The song plays and we see him tossing a football with neighborhood friends, home-movie style, the memories grainy and nostalgic. Their duality is immediately clear: The events are happy ones, but they are colored by what any adult would recognize as a disheartening loss of youth.

ABC Photo Archives via Getty Images

“The Wonder Years” used the song again in 1992, during a montage of Kevin’s schoolteachers that articulates the series’ affectionate coming-of-age arc. In retrospect, applying Mitchell’s emotions to a boy raving about his favorite English instructor flouts the way “Both Sides Now” (and Mitchell’s collective catalog) would soon seem gendered.

Take, for example, its inauguration into the romantic-comedy canon: 1998’s “You’ve Got Mail.” Corporate mogul Joe Fox (Tom Hanks) tells mom-and-pop bookstore owner and budding love interest Kathleen Kelly (Meg Ryan) that he “could never be with anyone who likes Joni Mitchell,” proceeding to mock the first chorus as they stroll through a New York City farmers market.“‘It’s cloud illusions I recall / I really don’t know clouds at all,’” he recites in a flippant tone. “What does that mean?”

Kathleen loves Mitchell, but Joe doesn’t know that. She says nothing in response, simply filing away the comment and moving on. Unlike “The Wonder Years,” Joe sees Mitchell’s sentimentality as meandering and effeminate. “You’ve Got Mail,” written by Nora Ephron and Delia Ephron, clearly refutes his argument, but not without tossing off a wink: “Men and women! So different, huh?”

Despite having been covered by Frank Sinatra, Willie Nelson and Bing Crosby, “Both Sides Now” is treated like a flag planted in a scrimmage concerning Mitchell’s credibility ― something to which ample female singers, even ones inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, are subjected. “You’ve Got Mail” came out at the start of the “TRL” age, when pop music underwent a gender regression. Girls were supposed to like boy bands and Britney Spears; dudes were meant to put on Korn and Eminem. Among older generations, it was safer than ever for men to dismiss someone like Joni Mitchell, who carried on about heartache and “dreams and schemes and circus crowds.”

Getty Images via Getty Images

By the time the movie “Life as a House” opened in 2001, “TRL” and its A&R-driven trappings were inescapable. Kevin Kline’s character, a cancer-stricken architect rebuilding his late father’s home, doesn’t even remember “Both Sides Now” when his ex-wife (Kristin Scott Thomas) puts it on, even though she used to play the song while rocking their now-grown son (Hayden Christensen) to sleep. (Never mind that they listen to Mitchell’s 2000 rerecording, fudging the infant-coddling timeline.) But, unlike “You’ve Got Mail,” the scene successfully evokes the ballad’s loveliness. Kline and Thomas slow-dance, the setting sun’s orange glow casting shadows as they sway, Mitchell crooning, “Something’s lost and something’s gained / In living every day.”

“Love Actually” also feels compelled to position Mitchell across gender lines. When British design executive Harry (Alan Rickman) tells his wife, Karen (Emma Thompson), that he can’t believe she still listens to Mitchell, Karen responds, “I love her and true love lasts a lifetime. Joni Mitchell is the woman who taught your cold English wife how to feel.”

If “Life as a House” and “The Wonder Years” present “Both Sides Now” as something plaintive, “Love Actually” turns it into a slice of outright despair. Harry gives Karen a copy of the “Both Sides Now” album for Christmas, though she assumes it’s the jewelry he’d bought for his flirtatious secretary (Heike Makatsch). Feeling dejected after opening the gift, Karen escapes to their bedroom to play the song, its rich orchestration and palpable grief mirroring her own tears. The way the lyrics shift between present tense and past tense ― once a source of buoyancy in Collins’ hands ― now feels especially heartsick, like romance that has spoiled: “Moons and Junes and Ferris wheels / The dizzy dancing way you feel / As every fairy tale comes real / I’ve looked at love that way.”

Alamy

Because “Love Actually” became such an overblown Yuletide lightning rod after its 2003 release, the film can arguably claim the definitive “Both Sides Now” scene. More compellingly, it joins “You’ve Got Mail,” “Life as a House” and “Steve Jobs” as one of several properties that has done more than just feature the song; all four include plot points about its impact, making it a repository for conflicted feelings.

As far as I can tell, seven years passed before another movie or TV program enlisted “Both Sides Now.” In 2010, as pop’s gender lines were fading somewhat, Mitchell’s symphonic arrangement scored an aerial performance during the Vancouver Winter Olympics’ opening ceremony. Somewhere, Karen was crying all over again.

And then, in 2015, “Mad Men” joined the “Both Sides Now” index, applying it to one of pop culture’s most scrutinized men. Here was a show about dualities employing a song about dualities to document its protagonist’s ultimate duality. Somewhere, Joe Fox was having a change of heart.

“Both Sides Now” scores the closing seconds and subsequent end credits of the Season 6 finale, “In Care Of.” After being told he must take a mandatory leave of absence from his advertising agency, Don Draper (Jon Hamm) brings his children to see the brothel where he grew up. The house is tattered and decaying, contradicting the ritzy Manhattan life that helps him ignore past traumas. The moment offers rare candor from a man who coats himself in lies, taking “Both Sides Now” out of the gendered gutter and onto the universal playlist. It makes sense that “Mad Men” would choose Collins’ version, though, which mixes Mitchell’s heavy lyrics with that ebullient harpsichord. It’s the light and the dark, swirled into one: emotional but not too emotional.

That’s how “Steve Jobs,” “Hereditary” and even “Toy Story 4” treat “Both Sides Now,” too.

In 2015’s “Steve Jobs,” the Apple co-founder’s 9-year-old daughter (Ripley Sobo) listens to Mitchell’s two “Both Sides Now” recordings on her Walkman, telling her father (Michael Fassbender) that the original is “girly” and the update “regretful” ― a tacit mark of Mitchell’s own maturation. (Smart 9-year-old!) “Steve Jobs” treats this as something of a turning point for its namesake: Is he too aged to become an attentive father, a gentler human?

“Both Sides Now” was meant to play an even larger role in the film, according to Aaron Sorkin’s shooting script. The final scene finds Jobs telling a college-age Lisa (Perla Haney-Jardine) that he’s “gonna put music in your pocket” ― in other words, that he will invent the iPod. “And now we hear the musical intro to ‘Both Sides Now,’ but it’s not the version we’re used to,” the screenplay reads. “This is the one Lisa was describing when she was nine. It’s a beautiful male/female duet with heartbreaking harmonies, more mature, wiser and haunted.”

In the finished “Steve Jobs,” director Danny Boyle swapped “Both Sides Now” for The Maccabees’ Coldplay-esque “Grew Up at Midnight,” which plays as Lisa opts to stick around for her father’s big keynote presentation. Regardless, Sorkin’s sequences were inspired by a passage from Walter Isaacson’s biography of Jobs, in which Jobs plays Mitchell’s two “Both Sides Now” tracks on his iPod, using the latter’s reflective lull to contemplate growing old. “It’s interesting how people age,” he says. Somewhere, Kevin Arnold’s eyes were watering.

It’s also interesting how people grieve (as in “Hereditary”) and how living creatures see themselves (as in “Toy Story 4”). Here, “Both Sides Now” takes on a metaphysical subtext that was, if you squint, there all along. “I’ve looked at life from both sides now” means, in the context of “Hereditary,” that the unravelling family at the film’s center has seen the proverbial other side; they have been kissed by death and demonism, and it did not go well. In that sense, Collins’ tune is a sort of dirge, preoccupied with a Faustian afterlife.

Disney

The “Toy Story 4” teaser highlights a similar, though less devilish, dichotomy. Woody, Buzz Lightyear and the other toys dance among the clouds, appropriately enough, Collins’ words seeming childlike: “Rows and flows of angel hair / And ice-cream castles in the air.” But when Collins gets to the chorus’ crushing admission (“I really don’t know clouds at all”), the scene screeches to a halt. An unfamiliar spork drifting next to Woody suddenly shrieks, “I don’t belong here!” The spork’s existential quandary ― why has it been classified as a toy? what is a toy? ― turns the playthings into dominoes, one crashing into the next. Their sunny reunion has been interrupted, just like the romance chronicled in “Both Sides Now.”

What a journey, from Joni Mitchell to Judy Collins and back again, from “The Wonder Years” to romantic comedies to horror to Disney. It’s hard to think of another song that’s been deployed in so many different manners so long after becoming famous.

At this point, no matter how clever its usage, this ditty feels a bit clichéd. It’s been covered more than 1,000 times, including by Sara Bareilles during the 2017 Oscars’ mournful “In Memoriam” tribute. With every film or television broadcast that puts it to use, “Both Sides Now” risks being taken for granted, its meaning shifted to fit storytellers’ whims. But the fact that it’s been repurposed this much, amid this many diverging mantras, makes all too much sense. Mitchell’s nostalgic, somewhat mystical lyrics can handle varying interpretations, but they always rely on the same thesis: Life, whether on the ground or in the clouds, contains agony and ecstasy.

Men and women know that, so in the end, the joke’s on Tom Hanks and Alan Rickman. Maybe if they’d listened to Mitchell ― or to Collins, or Kevin Arnold, or the women they were involved with ― they wouldn’t have wasted so much energy. Even toys know the power of “Both Sides Now.”

[ad_2]

Source link