[ad_1]

Warning: Spoilers for ‘Suspiria’ below!

In a room walled entirely with mirrors, ballet teacher Madame Blanc (Tilda Swinton) explains to Susie (Dakota Johnson), her star pupil, that to dance, she must hollow out her insides to become an empty vessel, allowing the spirit of the piece to inhabit her body.

“You empty yourself so her work can live inside you,” Blanc says, her dark silver braid draped down her back.

When Susie dances, she resembles a woman possessed: thrashing like a beast, slinking snakelike on the ground, hovering in the air like a lightning bolt. Her movements are, as Blanc put it, “a series of energetic shapes,” liberated from the world’s fussy conventions. They are fleshy configurations of poems, prayers, or ― as Susie adds ― spells.

Susie’s characterization makes sense, given that in Luca Guadagnino’s “Suspiria,” a remake of Dario Argento’s 1977 horror classic, the Markos Academy ballet school doubles as a coven. The movie begins when Susie arrives at the Berlin academy, having left her rural, Mennonite roots behind her. In spoken conversation, she is amiable and bashful, often pulling strands of her waist-length, coral colored hair behind her ear. Yet when dancing, Susie becomes someone else ― or something else ― entirely, something hungry and rumbling.

“Suspiria” neatly ties women’s creative power to that of occult forces, framing art as a sort of alchemy in itself. Blanc and her cohort stoke Susie’s transformation to climax using black magic spawned from an ancient witch named Helena Markos who believes herself to be one of three primordial Mothers who predate the creation of God. At the academy, it turns out, young dancers are trained to excellence and sacrificed to keep Markos’ rotting body from deteriorating.

“Suspiria” is fictional, but it’s grounded in history, in the equation of women’s creativity and witchcraft. For centuries, men have cast feminine transgressions as witchery, labeling women who consolidate power outside the patriarchal structures that bind them as enchantresses. And so, outsiders populated the occult space, and it became an abundant and accessible forum free of dogmas and gatekeepers. For women and others typically marginalized by conventional systems of governance and religion, the supernatural began to glimmer with promises of agency and actualization.

Courtesy Amazon Studios

Over the past several years, more and more young women have self-identified as witches, likely due, at least in part, to extreme disenchantment with men presently in power at every rung of mainstream society. But the tradition extends back centuries. Like in the latter half of the 19th century, when X-ray innovations and research into subatomic particles sparked interest in other kinds of invisible phenomena. The era spurred a surge of mediums ― most of them women ― who used the supernatural to directly access a supreme authority beyond the purview of men.

While “witch” was originally a label transplanted onto women by men, “medium” was a title women assumed for themselves. One such woman was Swedish painter Hilma af Klint, who channeled her visions from the spirit realm into cryptic and electrifying abstract paintings that predate Piet Mondrian and Wassily Kandinsky.

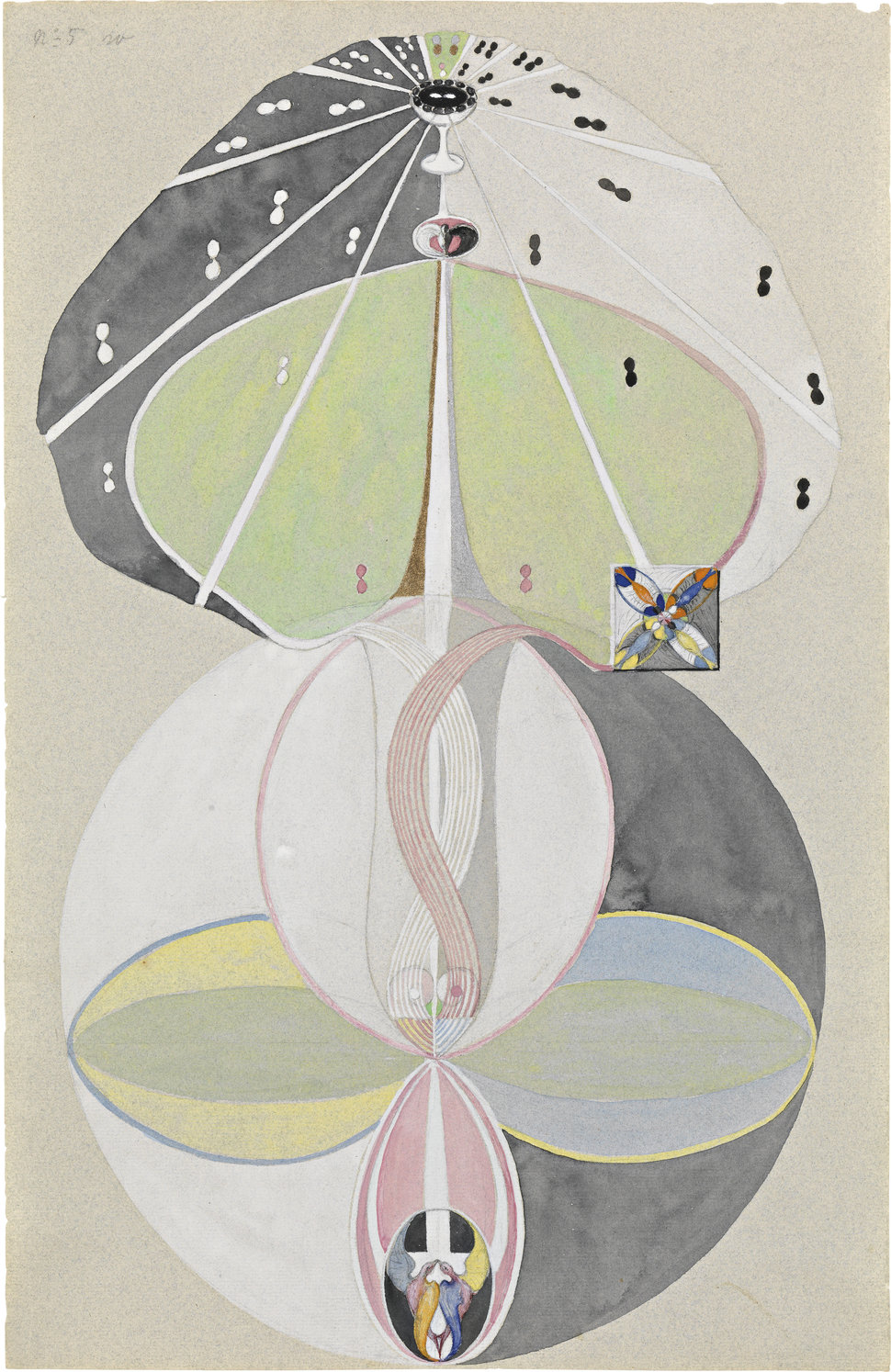

A retrospective of her work is currently on view at The Guggenheim, offering an intriguing foil to “Suspiria” and its witchy ways. Af Klint’s interest in the supernatural spiked after her sister’s death, when the artist was 18. She began holding seances regularly with four other women. Together, they called themselves The Five and communed with mystical spirits known as the High Masters ― more specifically, the spirits were named Amaliel, Ananda, Clemens, Esther, Georg and Gregor.

Af Klint eventually took on the role of the group’s official medium, relinquishing control of her body so it could become a conduit for the great beyond. In this liminal space, she transcribed automatic drawings dictated to her from on high. Like Susie, af Klint became an empty vessel for the sake of her work.

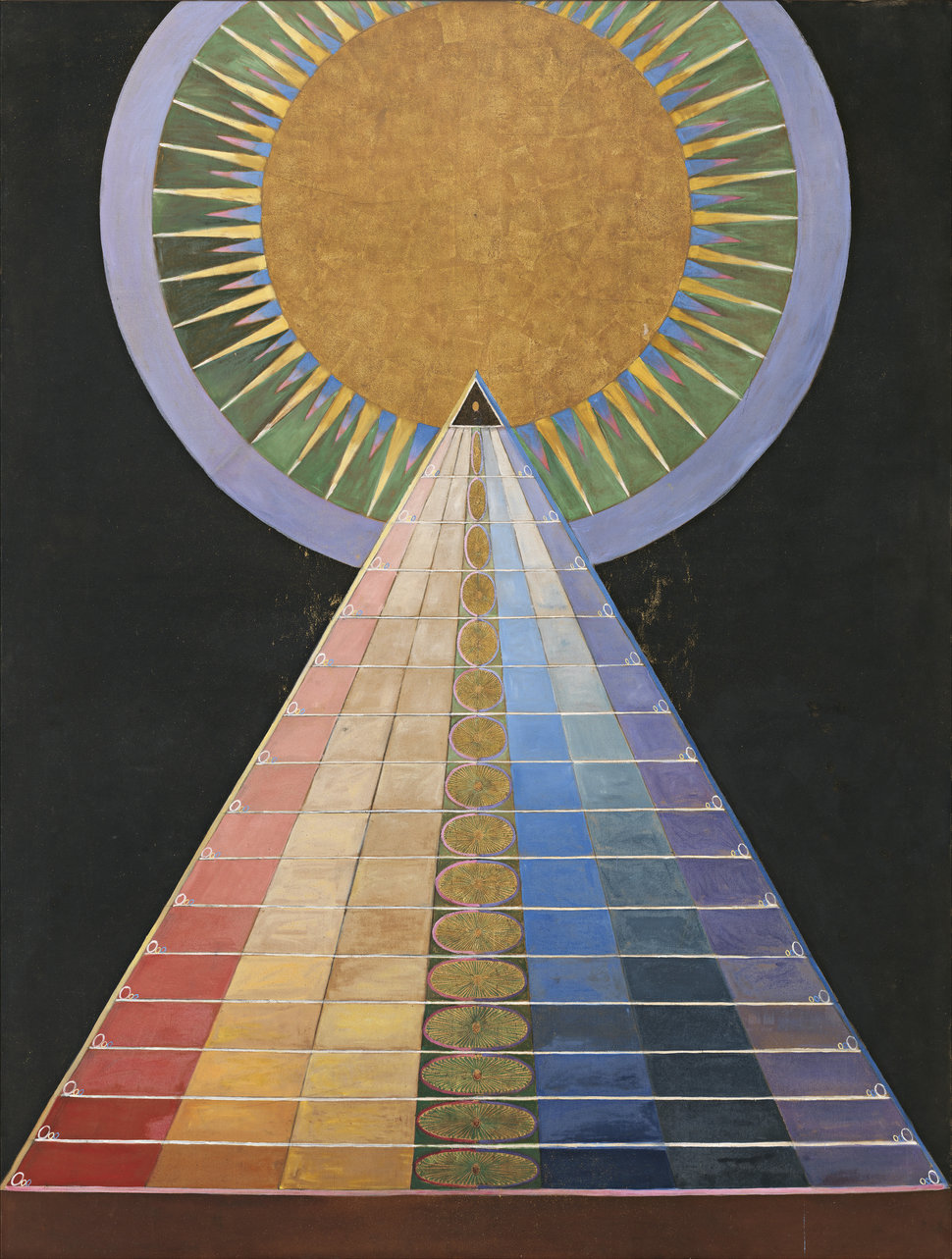

Albin Dahlström/Moderna Museet

Many female artists have depicted and embodied witchcraft in their practice, including Leonor Fini, Ana Mendieta and the mononymous Cameron. (Mendieta’s estate actually sued “Suspiria” for allegedly plagiarizing the late artist’s imagery in portions of the film. The scenes in questions were later cut.)

But af Klint typified a different supernatural persona: the mystic who served as a human conduit for the spiritual realm.

Her images didn’t depict earthly people, places or things; instead, they made visible emotions, presences and puzzles without concrete shape. They combined elements of Swedish folk art, scientific diagrams and arcane spiritual symbols. They were abstract art before it was known as such.

In 1903, The Five reportedly received a message from their High Masters commanding that their automatic drawings be fleshed out into paintings, which would one day hang in a large temple. One year later, these spirits called upon af Klint to lead what she called this “great commission.”

Although the other members of The Five were asked to assist af Klint in this task, they declined, fearing such close contact with the divine could drive them insane. Between 1906 and 1915, af Klint, working alone, painted 193 works, cumulatively called “The Paintings for the Temple.” The majestic depictions ― lavender, blush and tangerine ― feature snails floating among flower petals and curlicues, orbs morphing into unidentified organic organisms, punctuated by arcane messages scrawled in loopy cursive.

In 1930, af Klint specified these paintings would someday be housed in a “nearly circular” temple, with four stories connected by a spiral staircase in the center. Around the same time, architect Hilla Rebay began conceptualizing a cylindrical building, with floors connected by a curved ramp that coils skyward, to shelter the collection of Solomon R. Guggenheim. She described the not-yet museum as a “temple of non-objectivity and devotion,” adding, “‘Temple’ is nicer than church.”

Today, af Klint’s work hangs in a temple eerily similar to the one she predicted.

Albin Dahlström, the Moderna Museet, Stockholm

When “Suspiria” reaches its climax, Blanc and her cabal prepare an elaborate ritual involving nude women tangled into tessellations, furiously whipping their bodies to draw zigzags in the air. Some pull bloody entrails out of less fortunate ballet students while others chant baritone hymns. The purpose of the gathering is Susie’s sacrifice. By the time she arrives on the scene, she knows what is expected of her and is honored to oblige.

“Nothing will be left inside,” warns Helena Markos, whose archaic skin appears like beef jerky soaked in acid. “Only space, for me.”

The statement echoes the lesson Susie has repeatedly been taught, that art requires emptying, sacrifice and worship. “This isn’t for vanity,” Markos adds, to drive the point home. “This is art!”

Then, however, comes the twist: Susie ― and not Helena Markos ― is the almighty Mother Suspiriorum. She has been all along. Her dancing talent did not hinge on Madame Blanc’s soothsaying; the powers were her own.

“I am she,” Susie says breathily as a black lizard-demon sucks the life out of poor Ms. Markos. The demonic figure proceeds to murder all of Markos’ disciples ― sparing those who were loyal to Blanc ― as Thom Yorke sings moodily in the background.

“Death to any other mother,” Susie says mellifluously, as if it’s dirty talk. In this moment, she casts aside the woman who bore her, along with the notion that she ― as a woman ― should aspire to be anything but what she is. She massages her chest in ecstasy as piles of bloodied corpses build up around her. She then peels back the skin between her breasts to reveal a yonic opening. Inside, she’s dense with something wriggling, black and slimy.

The artist is no longer an empty vessel; she’s full and dark and vital.

Courtesy Amazon Studios

While “Suspiria” takes place within the entirely feminine ecosystem of the dance academy/coven, af Klint’s saga unfolded in real life. For the artist, a woman operating in the male-dominated art world, mysticism had its own pragmatic advantages.

As David Max Horowitz writes in the Guggenheim’s exhibition catalog, “Swedish art schools taught that women were capable only of copying, not of innovating.” So how was af Klint able to create such ground-shattering original work? Her association with supernatural forces helped flabbergasted men contextualize her. Her unprecedented visions didn’t come from a woman’s brain, they surmised, but from spiritual forces named Ananda and Esther. Somehow, the latter explanation was easier to fathom.

In 1908, af Klint took a break from her temple commission to take care of her mother, who’d recently gone blind. When she picked up her work again four years later, she assumed more control of her creative process. Instead of transcribing images dictated to her by the High Masters, she described receiving their cosmic messages and interpreting how to visualize them herself. As Horowitz writes, many female mediums similarly veered away from channeling after gaining recognition from the outside world, as if finally receiving the authority to speak (or paint) for themselves.

Af Klint stopped creating mediumistically entirely in 1916, though she continued making work. She knew none of it would be recognized during her time, so she mandated that her paintings would not be exhibited until 20 years after her death. In 2018, along with looking aesthetically contemporary, the paintings tap into the buzzy zeitgeist of occult spirituality. This was a woman who either clairvoyantly predicted the future or was endowed with exceptional shrewdness and strategy. It makes one question if af Klint’s spiritualist narrative is, in fact, savvy branding, a mindful middle finger to the patriarchal structures in the way of her due recognition.

“The world keeps you in fetters;” af Klint wrote in a notebook, dictated to her by the High Masters, “cast them aside.”

Albin Dahlström, the Moderna Museet, Stockholm

In his review of af Klint’s current exhibition, The New Yorker’s Peter Schjeldahl described the artist as a “a mystic primarily, though a dab hand at painting.” It’s a strange designation for a woman who is being belatedly credited with inventing abstract art. Later, Schjeldahl laments af Klint turning away from her mystic side, calling the decision “ruinous.”

Schjeldahl doesn’t hesitate to give his two cents as to what went wrong in af Klint’s career. “What happened, I think, was the loss of an extraordinary degree of freedom that had been vouchsafed to af Klint by her beliefs and guarded, in secrecy, from vulgar eyes. She had been alone on a peak, until she was cast down by a sense of being seen — and sized up — by what she took to be unimpeachable authority.”

Schjeldahl is precisely the kind of art world authority he describes, one who only subscribes to af Klint’s genius when its derived from an outside source. Contrast his take with that of New York Times critic Roberta Smith, who said, “To be honest, I’m not any more interested in the particulars of af Klint’s belief systems than I am in, say, the mysticism that Agnes Martin conveyed when talking about the delicate stripes and grids of her paintings.” The quality of the art supersedes the narrative of the artist, a privilege that’s often bestowed upon “neutral” artists who are white, straight and male.

“Suspiria” and af Klint’s retrospective offer interconnected accounts of supernatural women’s talent. In “Suspiria,” audiences are led to believe that Helena Markos’ coven makes Susie a great dancer, only to later reveal the power was within her all along. Meanwhile, the Guggenheim presents a woman whose occult associations freed her from the trappings of being an artist during her life, but threaten to damper her legacy today.

Together, the two cultural landmarks reveal how rarely feminine authorship is respected in its own right. I believe that af Klint, like Susie, had remarkable powers. But I don’t believe the High Masters communicated in ready-made canvasses. The author of these paintings, the inventor and executor of their groundbreaking formal qualities, is and has always been Hilma.

Self-possession, against all odds, is a mystical feat indeed.

[ad_2]

Source link