[ad_1]

Photo: Pedro Avedaño, courtesy Aldeide Delgado

Solid Abstraction: Strategies of Disobedience in Cuban Art includes works by ten Cuban artists living on and away from the island. All of them work with abstraction as both a trope and a strategy in their art.

Presented at the Miami Beinnale space in Miami, Solid Abstraction is curated by Aldeide Delgado. It is the first of a series of exhibitions resulting from Delgado’s 2017 award from TEOR/éTica, a Costa Rican nonprofit organization supporting critical thinking in the arts. Additional exhibitions will explore the theme of “Solid Abstraction: Political Directions in Central American and Caribbean Art.”

The intention of Solid Abstraction is to follow the trajectory of the Cuban abstract art tradition beyond its origins in the 1940s and 1950s. To this end, Delgado, focuses on a group of artists whose work in abstraction implies “an act of disobedience.” The show’s conceptual approach is based on the consensus-dissensus dichotomy of Jacques Ranciere, which positions disobedience as a strategy of creation.

Photo: Pedro Avedaño, courtesy Aldeide Delgado

Before turning to Solid Abstraction, it’s important to point out the 1997 exhibition Pinturas de Silencio—curated by José Ángel Vincench and Ramón Serrano and presented at Galería La Acácia as a collateral exhibition in the 6th Havana Biennial—as a vital antecedent on this topic. To present the continuum of Cuban abstract art, Pinturas del Silencio brought together works by artists in the earliest Cuban abstract movement—both in its concrete and informal aspects—along with Cuban contemporary artists whose works, inserted into the abstract tradition, implied a conceptual approach.

The text of that exhibition catalogue (published under the title Catacumbas del arte cubano) called attention to the surreptitious line that marks the survival of abstraction in Cuba. Pinturas del Silencio was the first important group exhibition to pick up this vital thread after the 1963 exhibition Abstract Expressionism at Galería Habana—a show that Hugo Consuegra later labeled, in his memoir, as the “swan song” of Cuban abstract art.

The works in Solid Abstraction begin from a common operational process: the abstraction or rewriting of a certain phenomenon or area of interest into codes that entail, as Delgado has written, “the transgression of the modern epistemological paradigm of abstraction.”

Photo: Pedro Avedaño, courtesy Aldeide Delgado

In this regard, Reynier Leyva Novo’s work Revolution is an abstraction (2013–2017) is paradigmatic. Taking as his starting point the emblematic posters of Soviet avant-garde artists—whose commitment to the reality that occupied them is essential—Leyva Novo empties them of their content, reducing them to mere formal language. By this process, he turns what once were messages of mobilization and political commitment into mere self-referential entities—alluding to both the conceptual dislocation of these works in the post-communist era, and to the banalization of the work of art, reduced to mere aesthetics.

Also referencing art history, August Macke/Dorothea Rockburne and Lygia Clark/Helio Oiticica (2014), both by Quizqueya Henríquez, propose dialogues that allow the artist to contrast opposite elements—the original and its copy, center and periphery, authorship and fair use, among others—which govern the classification and writing of the art history.

Courtesy David Castillo Gallery

Works by Filio Gálvez, Rodolfo Peraza and Francisco Masó focus on decoding concrete social phenomena.

Gálvez’s A la manière del Color-Field, GIS Studies (2017) is a series of collages in which units of color correspond to Google image searches of specific terms (anarchy, drugs, human rights, etc.). The artist had previously reduced the internet frequency band, resulting in the pure color fields that characterize this work.

Peraza’s Pilgram 1.0 (2015) is focused on public space as both a physical and a virtual entity. The installation is a live-streaming diagram of the first five internet hotspots opened in Cuba. Software compiles, in real time, the data indicating the apps most frequently used by the hotspots’ visitors. That data is translated into circular graphs showing the correlation between physical and virtual space.

Photo: Pedro Avedaño, courtesy Aldeide Delgado

The ongoing series Aesthetic Register of Covert Forces (2017–ongoing) by Francisco Masó documents the striped patterns on shirts worn by undercover government agents in contemporary Cuba. Masó synthesizes these stripes into abstract color bands that simultaneously identify and denounce the agents and their work.

Photo: Pedro Avedaño, courtesy Aldeide Delgado

Yaima Carrazana’s trilogy Declaration Letter No. 10. (2016) and Fifty Percent, I y II (2017) refer to the chromatic classification code of letters issued by the Dutch Ministry of Justice and Department of Taxes. The series reflects on such themes such as migration, assimilation into a new culture, and a questioning of private versus public space.

With a highly evocative content, Aurora De Armendi´s Libro de Colores II (El Monte y el Mar) (2016) is inscribed within visual poetry. It presents a contemplative and immersive attitude, in which the viewer’s physical contact with the work and its temporal elements are essential.

Courtesy Aurora De Armendi

Works by Ernesto Oroza, Glexis Novoa, and Refael Domenech explore the ephemeral and the provisional. Created in situ, these pieces presuppose the transplanting, into the white cube of the gallery, the concerns of everyday existence.

Models of Dispersal: Tabloid No. 29 & Tabloid No. 33 (2018) by Ernesto Oroza (in collaboration with Gean Moreno, Ana Olema Casanova and Annelys PM) is a site-specific installation. Olema’s calligraphy, generated from using spots of oil thrown onto the house of a Cuban opposition member (Tabloid No. 29) coexists with Félix Beltrán’s 1979 logo for his poster El aceite lubricante usado es útil otra ve (Tabloid No. 33). The installation generates an interesting historical-social counterpoint, reaffirmed by the texts created in both tabloids.

Photo: Pedro Avedaño, courtesy Aldeide Delgado

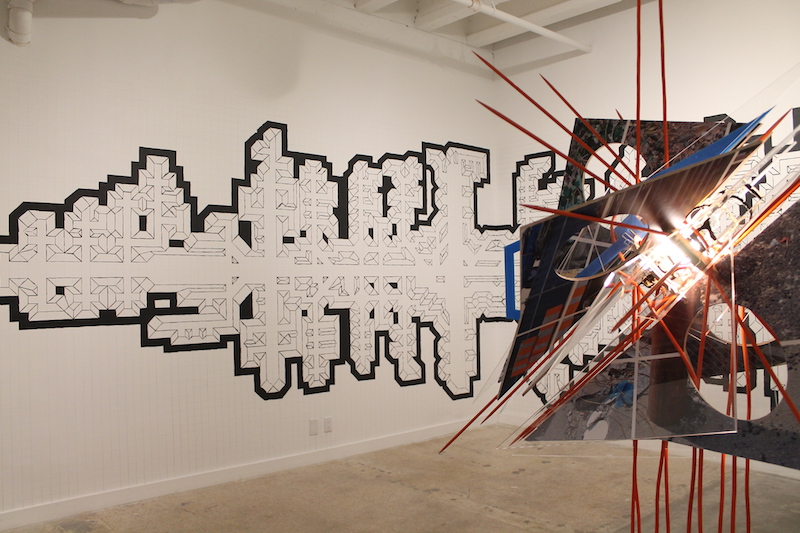

As an echo of the exploration of architectural, symbolic, and ephemeral elements, Glexis Novoa’s Bejuco(2018, seen in photo at top) is a drawing done directly on the wall–which, like a climbing plant, floods the space, creating a new, unintelligible iconography.

Sharing space with Novoa, Untitled (object of social conduct) (2018, seen in photo at top) by Rafael Domenech is a abstract-geometric chandelier. Both aesthetic and utilitarian, this mobile-concrete-light chandelier embodies the spatial concerns and researches into urban ecology that inform the artist’s latest works.

Solid Abstraction runs through June 25 at Miami Biennale, in the Design District.

[ad_2]

Source link