[ad_1]

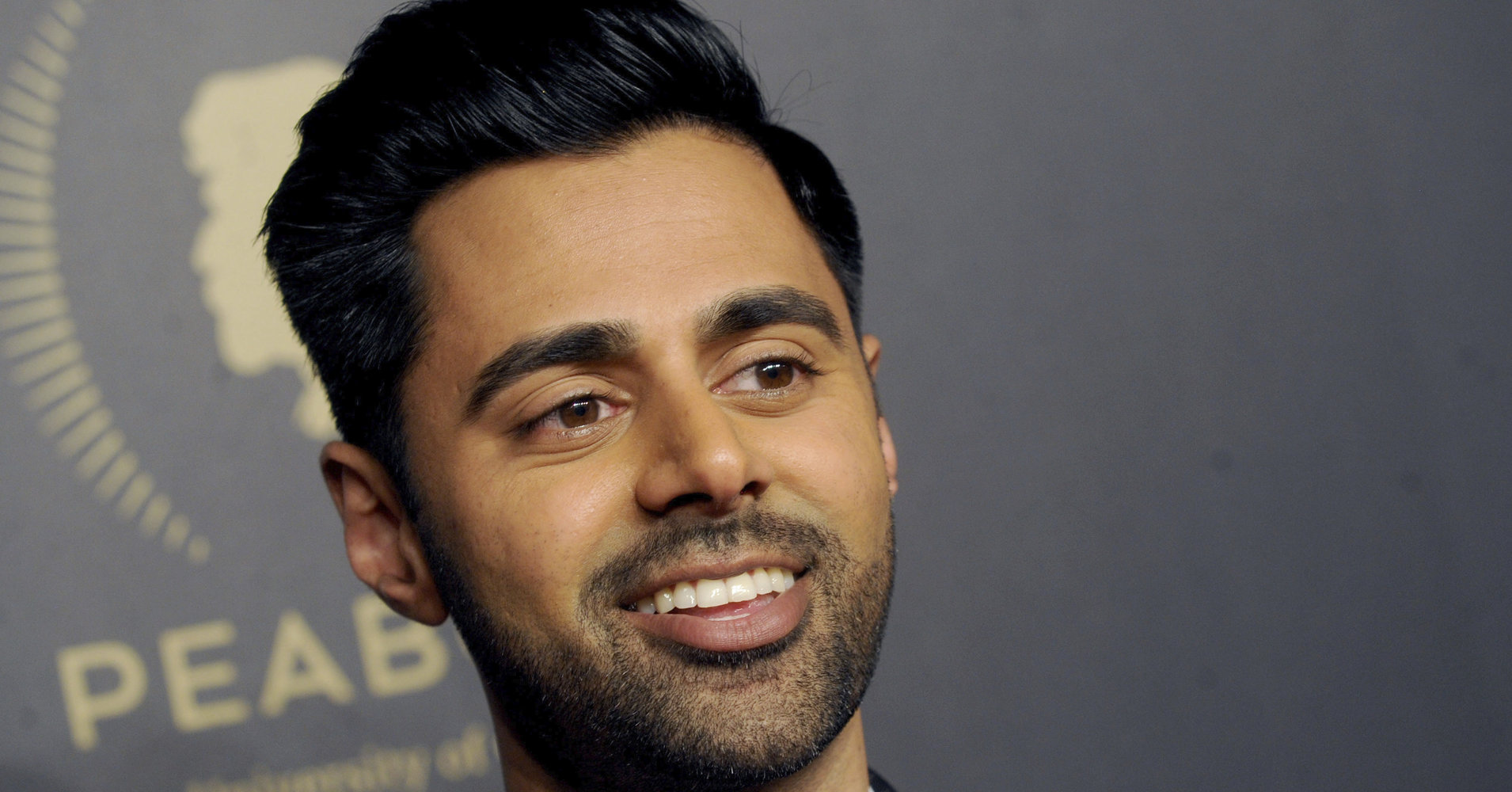

After the worst year for Saudi Arabia’s image since the 9/11 attacks involved several of its citizens, the kingdom began 2019 with a fresh controversy by asking Netflix to block Saudi users from viewing an episode of “Patriot Act with Hasan Minhaj.”

On Jan. 1, The Financial Times confirmed that Netflix had complied ― setting off international condemnation and a wave of renewed attention to a sketch Minhaj released months ago. (He appreciated the publicity.)

But beyond the absurdity and outrage is a reminder of a powerful trend that matters not just for the Saudis’ ongoing struggle to sustain their place in the world but for 1.6 billion people associated with the religion that was founded in the country, Islam.

The offending episode featured Minhaj saying this of Saudi Arabia’s de facto ruler, Muhammed bin Salman, and his connection with last year’s murder of Jamal Khashoggi: “It blows my mind that it took the killing of a Washington Post journalist for everyone to go, ‘Oh, I guess he’s not a reformer.’ Meanwhile, every Muslim person you know was like, ‘Yeah, no shit, he’s the crown prince of Saudi Arabia.’”

As Muslims like Minhaj in the U.S. and those elsewhere in the Muslim-majority world win bigger audiences, such observations will become a larger part of the global conversation. People will become more aware of critiques and nuances shared among Muslims for years but rarely included in the Western-driven coverage of issues like the Saudi regime’s behavior.

For Riyadh, that’s dreadful news. It becomes a lot harder to say the kingdom should get a free pass for denying adult women the right to travel without a man’s permission and giving its citizens almost no say over how the country is run if the regime can’t hide behind claims that that’s simply Islamic culture or the way Muslims want to live.

It’s inconvenient, particularly after the Saudis invested such immense amounts of time and money in trying to win influence by appealing to Muslims’ sense of solidarity, to have different kinds of voices and examples from within the community showing different ways to live and thrive. And it’s especially worrying that many of these newly visible Muslims seek to own their identities ― not to cede them, out of frustration or fear, to traditional stewards like Saudi clerics, or to simply assimilate for mainstream consumption.

Faced with this threat to their M.O. and the foreign security alliances critical to their power, Saudi leaders are, in classic style, so far only making things worse.

To understand why the situation escalated this way, consider that the modern state of Saudi Arabia is less than 100 years old. To become the kind of world player it is today, the kingdom has relied on its connection to Islam. The Saudi King uses the title “Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques” ― a reference to the Saudi cities of Mecca, where every practicing Muslim must travel once in their lifetime, and Medina ― in every official document.

The monarchy’s most important friends, notably the U.S., justify the relationship by referencing its authority in the Muslim-majority world. Around the region, the idea of natural Saudi leadership of the “Ummah” ― the global Islamic community ― carries weight among thousands of politicians and generals, oligarchs and day laborers. It doesn’t hurt that the Saudis’ oil wealth helps them buy support, but money is something many ambitious nations, from America to neighbors like the United Arab Emirates or Turkey, can offer. A connection to the divine isn’t.

The link in the international imagination between the modern kingdom and the preachings that began there 1,400 years ago is so strong that even Islam’s loudest critics take note ― and advantage. When Donald Trump lies about Saudi treatment of gay men in an attack on Hillary Clinton or when Islamophobe activist Pamela Geller publicizes Saudi excesses (inevitably inaccurately) to suggest that the way the kingdom operates is how Muslims want the world to run, they know they’re using one hardline regime to fear-monger about all of contemporary Islam and they know the tactic works.

But Saudi Arabia’s mantle is under threat. With more Muslims sharing particular experiences of their faith, their goals and their identities, the kingdom’s generalizations and claims to broad authority are becoming weaker. The internet’s made that easier in even the most hidebound Islamic societies. And in the West, years of activism have successfully pushed institutions to better represent younger Muslim communities, like immigrants or second and third-generation Americans.

That’s something Netflix considered in offering a major platform to Minhaj ― “a person who relishes and catalogs the cultural specificity of his life,” as a recent vivid profile of him put it ― in the first place.

A California-born child of Indian Muslims, Minhaj melded general American concerns about Saudi Arabia ― what it means for it be a close U.S. partner, what it’s doing to civilians in Yemen and independent voices at home ― with a particular discomfort for his own community.

“As Muslims, we have to pray toward Mecca,” he said in the Netflix episode. “We access God through Saudi Arabia, a country which I feel does not represent our values.”

It’s a sentence many Muslims wary of the austere Saudi state-sponsored interpretation of Islam ― and its influence in other Muslim-majority societies, from Southeast Asia to North Africa ― would nod their heads to, even if official politics, clerical circles and Muslims’ desire to visit the holy sites in the kingdom (something Minhaj has done) sustain a public posture of respect.

Sensing what’s coming and how it could challenge their regime’s critical coziness with Western patrons, top Saudis are already trying to maintain their comfortable status quo. That’s the driver behind efforts like Saudi media’s smearing in recent months of Reps. Ilhan Omar (D-Minn.) and Rashida Tlaib (D-Mich.), the first Muslim women elected to the U.S. Congress.

“These regimes have always benefited from the false choice they present to policymakers in the West — in Muslim countries, they say, extremists are the only alternative to dictators,” journalist Ola Salem wrote. “That argument is eloquently undermined by American politicians who share those regimes’ religion, but not their cynicism about democracy.”

Such figures have independent knowledge and thoughts on the Muslim-majority world, she noted ― they’re less likely to buy whatever the Saudi lobby in Washington is selling, such as panic about the kingdom’s regional rival, Iran.

While the episode ban remains in place, Minhaj’s quick viral response to the kingdom shows that the Muslims who’ve fought stereotypes, racism and skepticism on top of all the other challenges to entering public life increasingly are unlikely to be cowed by Riyadh.

“I can’t speak for all American Muslims but what I can tell you is… it is a stain on the perception of Islam and Muslims,” Abdul El Sayed, a young Democrat who most recently sought the party’s gubernatorial nomination in Michigan, said of the kingdom.

One of a growing group of Muslim Americans who are making waves in left-wing politics, he said a tougher U.S. stance toward the Saudis would serve a range of progressive ideals: rejecting the regime’s human rights violations and regressive interpretation of Islam, and challenging a key player in the global oil market.

Saudi leaders now have to figure out how to handle and respond to these louder and louder voices.

They might seek advice from an increasingly close friend in a parallel situation: Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, who despite Israel’s status in Jewish theology and history has aligned himself with right-wing leaders in Europe and the U.S. whose political bases include known anti-Semites. Netanyahu’s approach, described by his supporters as a way to better protect his nation, helps these right-wing movements fight claims of prejudice ― much as the Saudi reluctance to criticize Trump’s Muslim-focused travel ban did for the U.S. administration. Meanwhile, the fighting within the larger Jewish community over Israel’s direction only becomes more heated.

Whatever the Saudis choose, they can’t ignore the growing conversation.

“I think it’s incumbent on all Americans to stand up and say enough is enough: We are not going to be part of empowering a despot who murdered his own citizen,” El Sayed said. “I can think of nothing more American than that.”

[ad_2]

Source link