[ad_1]

Satanists, it turns out, are everything you think they’re not: patriotic, charitable, ethical, equality-minded, dedicated to picking up litter with pitchforks on an Arizona highway.

That much is clear in the fantastic new documentary “Hail Satan?” — which chronicles the rise of the Satanic Temple, a movement that has little to do with its titular demon. Founded in 2013, the organization is equal parts modern-day religion, political activist coalition and meta cultural revolution. By reclaiming the pop iconography that has long frightened evangelical America ― devil worship, ritualistic sacrifice, horns, pentagrams, the so-called Black Mass ― the Satanic Temple aims to catch people’s attention and then surprise them with messages of free speech, compassion, liberty and justice for all.

No wonder membership has spiked since Donald Trump’s election.

Penny Lane’s film, opening in limited release this weekend, enthusiastically dispels myths about the history of satanism, using the controversial belief system as a lens to survey the myriad ways our government has made Christianity the national religion. If a state legislature votes to erect a Ten Commandments monument, the church argues, why shouldn’t the Satanic Temple be able to introduce a pillar of their own? It’s only fair.

I sat down with Lane in New York for a fascinating conversation about making the movie, how Hollywood has popularized erroneous devil worship clichés, the satanic-panic frenzy of the ’80s and ’90s, and the ubiquitous theocratic motto “In God We Trust.”

At what point did you know what this movie would be? It’s more than a profile of an organization or an exhaustive cultural history.

There’s a moment early on in my research, just in my reading, where I realized that I was completely wrong about something. I thought, upon casually scanning headlines about this group and what they were up to, that the Satanic Temple was like a fiction ― a political troll satire thing, like The Yes Men, where they were pretending that they were members of an imaginary organization in order to make these points. The moment I knew what the film would be was when I realized that that was totally wrong.

What would a new religion, starting from scratch, do if it wanted to make sense in the world we actually live in?

Penny Lane, director of “Hail Satan?”

The [group] perhaps had started as that, and then had very quickly evolved to be something real, where there is a thing called the Satanic Temple, and there are members, and they have very particular beliefs, and they’re not just trolls. I was like, “Oh, that’s a cool story.” It was almost the same as the birth of any religion; first, you have to have some publicity stunts to get attention ― some miracles, maybe. From there, maybe you have something to say, and then people would join. I feel like I had never seen that story: watching a religion get born, right before our eyes.

The story of the Satanic Temple is one of free speech. Did you always know the movie would be about that?

Sort of, yeah. I don’t think it’s really about free speech. The politics of what they’re doing is obviously really important, and as a particularly American phenomenon, they’re trying to uphold the First Amendment. Their activism is not particularly radical. They’re not anarchists, they don’t want to burn it all down.

The freedom-of-speech thing, for me, comes under the headline of “a new religion for modernity.” What could religion be in the 21st century? What would a new religion, starting from scratch, do if it wanted to make sense in the world we actually live in? Would it be about nonscientific, paranormal claims about invisible people in the sky, or would it be about embracing the centuries of progress that the Enlightenment project has given us? It seems like that would be a better religion.

You started working on the film before Trump’s election. Once his presidency began, did anything shift in terms of what the movie was trying to say?

Like everything else, it’s the same answer. Everything was suddenly more urgent. Trump’s alliance with the evangelical community [has] none of the values but all of the power grab. It was very frightening for a lot of people, who ended up with people like Mike Pence, who is legitimately a theocrat. He would love for the Bible to be the document that we obey as Americans. Then, someone like Betsy DeVos: still super evangelical, loves prayer in school.

It was super easy, if you were me, under Barack Obama, to not pay attention. I don’t even know what that guy was doing for, like, six months at a time, Now you’re hyper-aware and fearful. So I think for a lot of people, this story took on a lot more urgency. And certainly, membership in the Satanic Temple spiked after Trump’s election. Many people that I spoke to told me that Trump’s election was a turning point for them.

The moment in the film that stunned me the most is when a Satanic Temple member reframes satanic panic as the Catholic Church projecting its own history of abuse onto the public. We all know how ridiculous and sensationalistic that era was, but I’d never heard it put that way. It’s pretty stunning.

I had the same response to that. I will say this about that: The entire history of satanism is one of projection. Satanic panic is one example. All the way up until 1966, there were no people who called themselves satanists. There literally weren’t any. There was a fear that manifested into an elaborate fantasy on the part of the Catholic Church, mostly, if you want to point a finger somewhere.

Then you have this imaginary idea that everywhere around you, there are these devil worshipers who are doing these terrible things. In many cases ― well, in all cases ― that was used as justification to kill people, whether it was witches or, for many millennia, the Jews. All the same, atrocities were attributed to these groups of people by the Catholics as a way of murdering them. Then you go into the satanic panic and you see this same thing. I was blown away as well.

Was there a singular moment like that for you ― something that made your jaw drop?

I would say the main thing for me was the moment when I suddenly turned to my producer and said, “How is our national motto ‘In God We Trust’?” I’m a lifelong atheist. Somehow, I never realized that that is so weird.

And it’s ubiquitous. It’s on every dollar bill you touch.

What they do, the satanists, is they awaken you to look around and see the world you actually live in. Suddenly, you do notice the Ten Commandments monuments on the statehouse lawn. Suddenly, you do notice that we think it’s normal that people pass out Bibles in public school. These are all actually not normal, in some sense. It looks normal to us because we’re so used to it.

Of course, it’s a long story, but the most recent iteration of putting God in government was really only 50 years ago, as opposed to 200 or 300 years ago, which is what I would have assumed. I think that, for me, was the biggest mind-blowing thing. It’s actually a quite modern phenomenon.

If you went home and Googled it, you’d see that there’s hundreds and hundreds of these local fights happening where some senator somewhere wants to put the Ten Commandments on statehouse property or some senator somewhere wants to have prayer in public schools or write “In God We Trust” on police cars. Those battles all look really stupid and petty. Who cares if the Phoenix City Council wants to have prayers before their meetings? But when you look at them in totality and start to understand, it’s not like they’re going to stop. It’s not like, “Oh, we got ‘In God We Trust’ on the police car, now we’re done.”

It’s evidence and ammunition for the next battle. With these Ten Commandments monuments, people now suddenly believe that this is an integral part of our American history, when in fact, they’re movie props. That was very chilling for me.

Initially, someone like [Satanic Temple co-founder] Lucien Greaves would make that point, and I’d think, “OK, that sounds a little bit paranoid, or a little bit of a conspiracy theory; it’s probably not that serious.” As I did the research, I realized that he was completely right. I didn’t know the extent to which there’s an organized, very well-funded, very effective lobbying happening nationwide. You don’t have to be paranoid to think, “Just because we have a liberal, secular democracy now doesn’t mean we will always.”

It’s not saying it’s gonna happen tomorrow, but it has happened in the past. Iran was a secular nation [until 1980], when all a sudden, it became a theocracy. It’s something that awakened a kind of urgency in me. I never thought there was any reason to be at all concerned. It’s certainly much more possible every time you let one of these small steps get taken.

I’m fascinated by the way devil-worship imagery has infused pop culture. A few years ago, when the horror movie “The Witch” came out, the Satanic Temple was very supportive of it, which is interesting because that movie embraces the occult in a way that runs counter to the organization.

There’s never been a fictional movie about satanists that was even kind of accurate.

Right, one that doesn’t involve some type of sacrifice or bloodletting.

Not even close. It would be really interesting to see if someone could ever do that. I think it would be so confusing.

Did you talk to folks about cinematic depictions of satanism?

It’s so weird and interesting to watch that negotiation take place. You’ve got this weird cycle ― you see it all the time, with “Sabrina” and “American Horror Story” and whatever ― where you have these depictions of devil worshipers, and it attracts rebellious teenagers to this idea of satanism. Any of them who actually develop any interest go to the bookstore and learn about Anton LaVey [who founded the Church of Satan in 1966]. Then they’re like, “Oh, this isn’t actually at all what ‘Sabrina’ said it was, but it is interesting to me.”

If you’re a certain kind of provocative person who likes to troll people, you might be into putting the pentagram on your shirt. But there’s no satanists in the way that you think there are in the movies. Then you end up with more satanists of the real kind because there’s a weird back-and-forth where they take the iconography and the imagery, all of which, as you said earlier, are projections. There never was a Black Mass ― it was only a fantasy on the part of Catholics. Then you’ve got the real satanists doing a fake Black Mass. It just confuses people to no end. I try to explain it to people and I’m like, “They really want you to think about the fact that there never really were any satanists.”

The imagery becomes meta. It’s all about reclaiming what people assumed was happening in suburban basements or whatever.

It’s a very weird relationship between the pop-cultural fantasy of satanism and the reality of satanism, and the back-and-forth between them is very complicated. Anton LaVey loved that shit. He circulated lots of rumors.

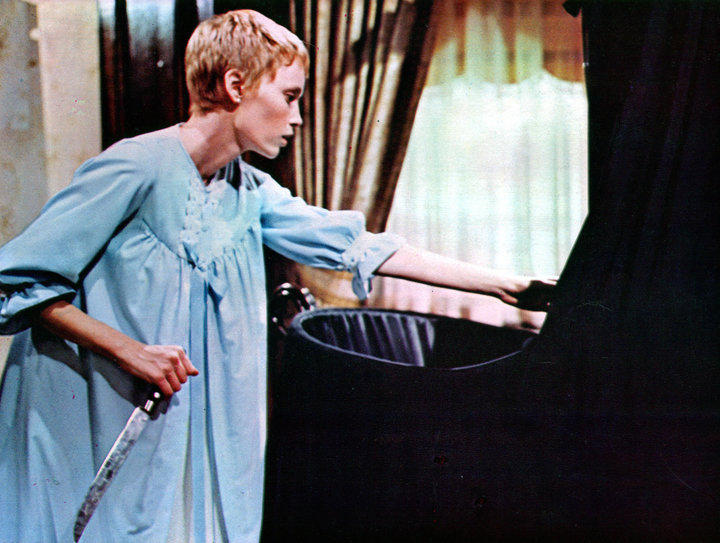

I think it’s been demonstrated that it’s not true, but he wanted everyone to believe that he actually played the devil in “Rosemary’s Baby.” Even while he’s saying satanism is about atheism, freedom, individual values [and] sexual liberation, he was also really into the idea of being associated with “Rosemary’s Baby.” You can’t do satanism without the popular fear of Satan, so those movies help. They continue to keep Satan relevant.

No one cares if you want to be an atheist and go home and yell about how dumb Christians are. They really do care if you’re a Satanist. You get a lot of attention.

It’s like reverse-engineering the way that people develop a belief system. I would have thought of it as bad branding, like, “Hey, you guys, movies like ‘Hereditary’ are not the way it works.”

It’s not bad branding. It just helps them seem more relevant. At the end of the day, if you think satanism is bad branding, you’re just not a satanist. For them, it can’t be anything else. It’s not like they were looking around for the right symbol, considered a spaghetti monster and went with satanism.

Right, and it’s dependent on the idea that Satan is a concept that comes from organized religion.

Unlike the spaghetti monster, they want to be part of culture. They want to be like, “We, as Western civilization, have been having this now 2,000-plus-year-old conversation about good and evil and what it means to be a human and how we got here and how we’re supposed to live. We want to be part of that conversation. We don’t want to be like Richard Dawkins and just go over there and say, ‘Look at all these idiots. Fuck ’em all, wait till they’re all dead. Can’t wait for the future secular world.’”

They want to be part of the conversation, so it has to be Satan, because that’s how they get to be a part of the conversation. No one cares if you want to be an atheist and go home and yell about how dumb Christians are. They really do care if you’re a satanist. You get a lot of attention.

What’s the thing you left on the cutting-room floor that was the hardest to let go?

All this satanic panic stuff. We had so much more. It’s years and years, with all these cases. The power of the human mind ― it’s just nuts. I think about all those kids who were convinced by adults that they had been basically fucking raped by the devil and that they were irrevocably harmed by it, walking around as adults. That’s so disturbing to me. Those poor people. I think that was the hardest thing we cut.

We did so much really good research and interviews on that topic, and then we ended up with one scene because it was just so much. To start to get into false memories, multiple-personality disorder, dissociative identity, all these psychological ideas that allowed this concept to continue, and what happened with this crazy alliance with feminists who were like, “Believe the victims, child abuse is bad,” alongside these crazy people who were just imagining devil worshippers everywhere. Gloria Steinem was a big part of this. It’s a long story. Once we had to start explaining what dissociative identity disorder was, we were sunk.

The fact is, there would be no Satanic Temple without the satanic panic. It’s very generational. It’s people our age, because we’re like, “Oh yeah, right. We all learned about satanism on daytime television.”

Based on your research, what really was satanic panic? What was actually going on?

That’s what’s crazy. When I talk to all these experts, there’s so many factors. Anyone who gives you an answer to that is leaving out something. It really was the growth of an understanding of domestic sexual violence as a very important, real thing in the ’70s. There was a moment: “Fuck, most rape is happening in the home.” That happened, then there was the stranger-danger panic, which was a whole other thing. Then there was the rise of the Christian right, and their dominance in popular culture through televangelism. Then you had women going into the workforce in record numbers, leaving their kids in daycare. A lot of anxiety about that, and guilt: “What’s happening with our children while we’re off at work? Is this good for society?”

There was so much going on that it’s hard to blame any one person, so then no one got blamed and no one ever apologized. Everyone had their little piece to the puzzle. Why did it end ― which is at least an equally important question ― is also unclear. It just sort of did. It wasn’t because we as a society all woke up one day and had a conversation about this, because it seems like we never did that.

For someone who wants to explore more about the history of satanism, what else was part of your research?

I was reading First Amendment law, trying to understand the framework. Jay Wexler was our legal expert ― I read a bunch of books by him. Then Kevin Kruse was our historian ― he’d written a really good book called “One Nation Under God” that helped me understand that history. Then there was Jesper Petersen, who was our religion expert. I’d read a bunch of his books and articles about satanism as a religious phenomenon of modernity, and that was super helpful for me to understand, from a religious-scholar point of view, what this meant.

There was another expert who we didn’t get to use, Debbie Nathan, who wrote the seminal book on the satanic panic, “Satan’s Silence.” Then another expert we didn’t end up using was Kathleen Stewart, who’s a journalist, whose beat has been the attempt on the part of evangelicals to take over the government. Amazing story — who’s making the plan happen, who are the lobbying groups, what is the model legislation that’s being written by these lobbying groups, what’s their stated agenda. Also, we didn’t even do the interview, but we wanted to get a Christian theologian who could talk to us about the history of the devil. It’s not like there’s one representation of the devil. In fact, there was no devil in Christianity for quite some time. Only in retrospect did we start saying, “Oh, the snake in the garden of Eden is the devil.”

Because in the Bible, Satan’s just a fallen angel.

Yes, exactly. The history of Lucifer and this idea of Satan, which was a word out of Judaism that just meant “the adversary,” combined and created its own new narrative. Again, we keep rewriting the Bible, so then future generations of scholars go back and read the Bible and say, “Look, here’s Satan all along.”

Part of the message of the Satanic Temple is that the meaning of symbols changes. They’re malleable to culture. Things change over time. It’s not insane to say this Baphomet image means freedom and diversity and reconciliation of opposites and openness to all. Just because you think it means the devil and evil and baby sacrificing doesn’t mean that’s what it means. That’s why they were so mad at “Sabrina” when they ripped off the Baphomet monument and put it in that show as a monument that means evil. They’re like, “We worked really hard to make that monument. All of our lawsuits were proposing a meaning for this monument. And if that monument ever did get installed on a statehouse lawn, the meaning of it would be religious diversity.”

There’s no particular reason we have to hold on to this idea of Satan as the ultimate embodiment of evil. I think that’s a really important thing. The meaning of these images is not settled. The Ten Commandments monument, the meaning of it 60 years ago was “go see this Charlton Heston movie.” Now it’s like an important part of our heritage as a nation, the idea that Ten Commandments are so foundational. You’re like, “This is not what it was one generation ago.”

This interview has been edited and condensed.

[ad_2]

Source link