[ad_1]

Vladimir Putin was reelected president of Russia on Sunday in a vote that was heavily managed and facing virtually no opposition.

Putin — who won a fourth term, which will keep him in power until 2024 — declared victory after Russia’s central election commission said he had won 75 percent with 50 percent of the vote counted.

His nearest opponent, the Communist party candidate, Pavel Grudinin, had 12.7 percent. After declaring victory, Putin appeared at a rally held at Moscow’s Manezh square in front of the walls of the Kremlin.

“Thank you,” he told the crowd. “That we have such a powerful, many-million strong team. It’s very important that you preserve this unity.”

Krill Kudryavtsev/AFP/Getty Images

Krill Kudryavtsev/AFP/Getty ImagesPutin’s win had never been in doubt. After 18 years in power, he has near total dominance of Russia’s media and his grip over the country’s political scene is complete, with almost no substantial opponents permitted and approval ratings kept at over 80 percent.

Anton Vaganov/Reuters

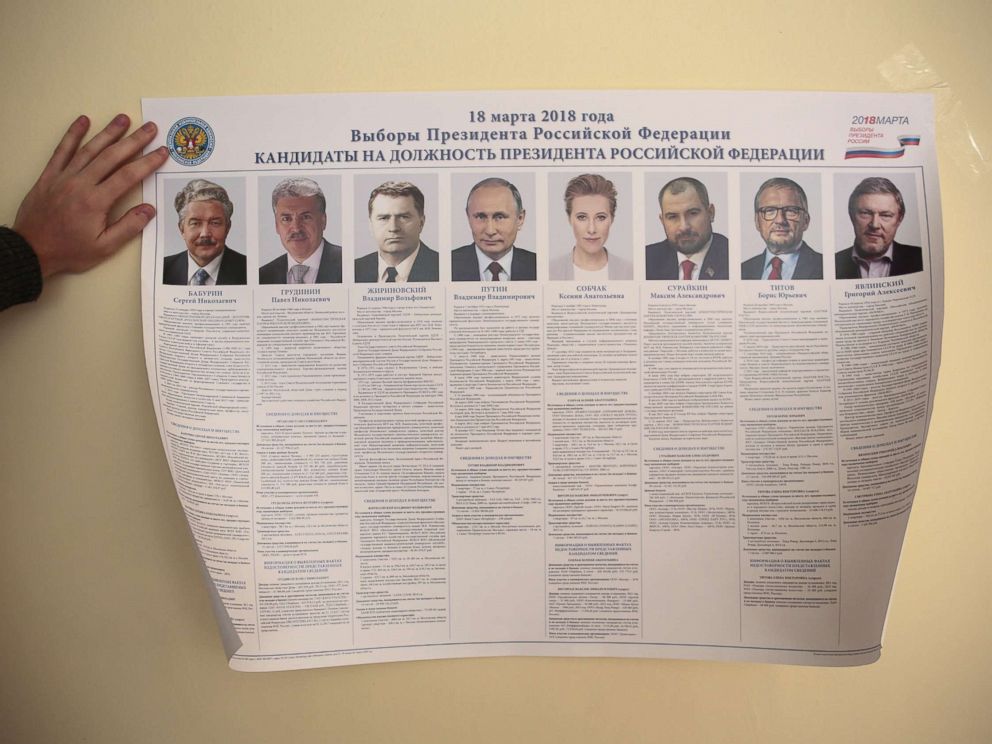

Anton Vaganov/ReutersEven Putin’s seven opponents never suggested they could win. His most troublesome opponent, Alexey Navalny, was kept off the ballot by a fraud conviction he said is trumped up.

Instead, authorities had worried about turnout. They launched an unprecedented campaign to ensure a maximum display of support for Putin. Prior to the vote, the Kremlin had indicated it wanted a 70 percent turnout; it had told authorities to make the election like a “holiday.”

David Mdzinarishvili/Reuters

David Mdzinarishvili/ReutersBy all appearances, officials heeded that call. As in Soviet times, officials put on attractions around polling stations.

Outside polling station 1869 in Nagatinskii in Moscow’s southern suburbs, a woman led an aerobics class to energetic techno music. Some voters danced in a circle; as at many others, stalls sold pies and tea.

“It reminds me a little of when I was young,” said Mikhail Goranin, an entrepreneur who had voted for the Communist, Grudinin. “For people, it’s a holiday.”

Authorities had also turned to other methods to boost voter numbers — across the country, there were reports of ballot stuffing.

Russia has installed a video camera system covering polling stations and Russia’s internet was full of clips showing fraud. In some, local election officials could be seen stuffing in wads of ballots; some tried to move balloons, put up to decorate polling stations and to block the cameras.

In one video, from Yakutia in Russia’s far east, a man was so busy stuffing ballots that a queue of voters formed behind him.

There were also frequent reports of people pressured to vote en masse.

The Associated Press quoted Yevgeny, a 43-year-old mechanic voting in central Moscow, who said he briefly wondered whether it was worth voting.

“But the answer was easy … if I want to keep working, I vote,” he said.

Maxim Shemetov/Reuters

Maxim Shemetov/ReutersNavalny, the barred opposition leader, had called a boycott of the election. It was unclear late Sunday how effective that had been.

Navalny and other opposition leaders, though, mobilized tens of thousands of volunteers as election monitors. At his headquarters in Moscow, about 30 volunteers fielded calls in from monitors, while an election live-broadcast ran on Navalny’s popular YouTube channel.

Navalny’s staff said they had approximately 33,000 registered monitors spread across Russia.

Even before counting finished it was clear that amid the voting push, Putin’s tally was the largest he has ever received. His highest previous victory was 71.31 percent when he was reelected in 2004.

The election was heavily crafted by the Kremlin, which allowed novel candidates to run. It moved election day to the anniversary of Russia’s annexation of Crimea, an event that hugely boosted Putin’s popularity. With the outcome preordained and with so much orchestration, the election often felt less like a race than a giant show, planned and executed by the Kremlin.

Sputnik/Alexei Nikolsky/Kremlin via Reuters

Sputnik/Alexei Nikolsky/Kremlin via ReutersThe overwhelming numbers were, therefore, accompanied by a certain perfunctoriness. At the victory rally in Moscow there was no euphoria; although the crowd was large, the atmosphere was somewhat limp.

Putin spoke for less three minutes; while those at the front cheered, many in the middle of the crowd hardly looked up, talking amongst themselves.

When Putin shouted, “We are destined for successes, right?” those in the middle, half-amused, cheered, ‘Yes!”

Many people appeared to arrive in organized groups. At Putin’s last victory rally in 2012, large numbers of attendees were seen being corralled and some were paid.

Maria, an 18-year-old student, told ABC News her college strongly urged her to come.

“They forced us to come,” said Maria, who declined to give her surname for fear of reprisals.

Perhaps the most dramatic contest of the day occurred on the sidelines of the vote, between two opposition figures.

Ksenia Sobchak, a millionaire celebrity journalist and former reality TV star, whose father was Putin’s political mentor, had run on a Western-orientated liberal platform.

She had been accused of coordinating her run with the Kremlin and was heavily criticized by Navalny as a “spoiler,” intended to split the opposition vote while lending legitimacy to the election.

As polls closed, Sobchak appeared on Navalny’s election live-stream show to ask him to unite with her newly founded party. Navalny refused, saying she had been used by Putin.

“I will judge you by your actions,” he told Sobchak on air. “And your actions are disgusting.”

“You are his instrument, nothing more,” he said.

The short campaign in some ways has been a sideshow for Putin, who campaigned little, appearing before large election crowds only twice.

In any case, with state TV most days showing Putin solving problems in the country, Russia in some ways lives in permanent campaign mode.

With so much effort put into producing such a decisive win ahead of the election, some in Moscow have spoken of it as a declaration of Putin as president for life.

After his win he was asked would he still be in power in 2030.

“Let’s count. It’s ridiculous, what, am I going to sit here until I’m 100? No,” Putin said.

[ad_2]

Source link