[ad_1]

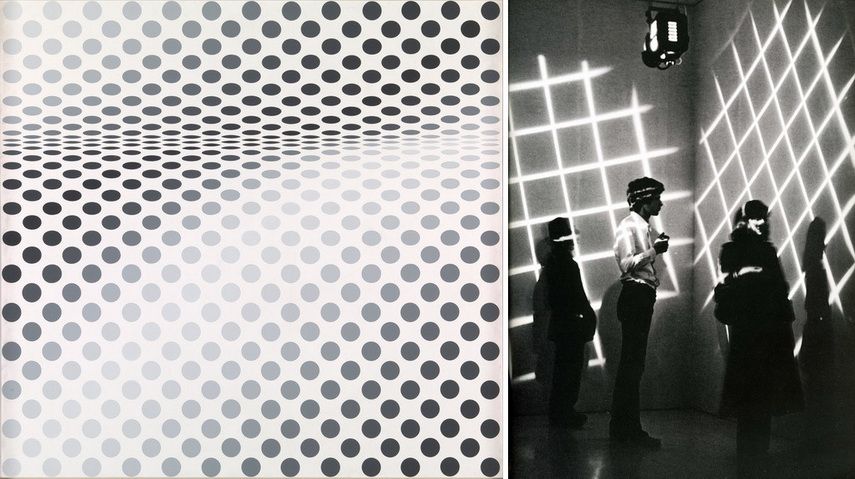

Aside from the emergence of Pop Art in America and Nouveau realism in Europe, movements that were mostly rooted in traditional media such as painting and sculpture, the 1960s brought yet another, but far radical phenomenon called Op Art, which was based on the intersection of art and technology with a specific focus on explorations of optical effects.

As a matter of fact, Op Art can be traced from the avant-garde experiments developed around the Bauhaus school as well as the practices of Russian Constructivists, while the leading practitioner of this particular style established during the 1950s was Victor Vasarely.

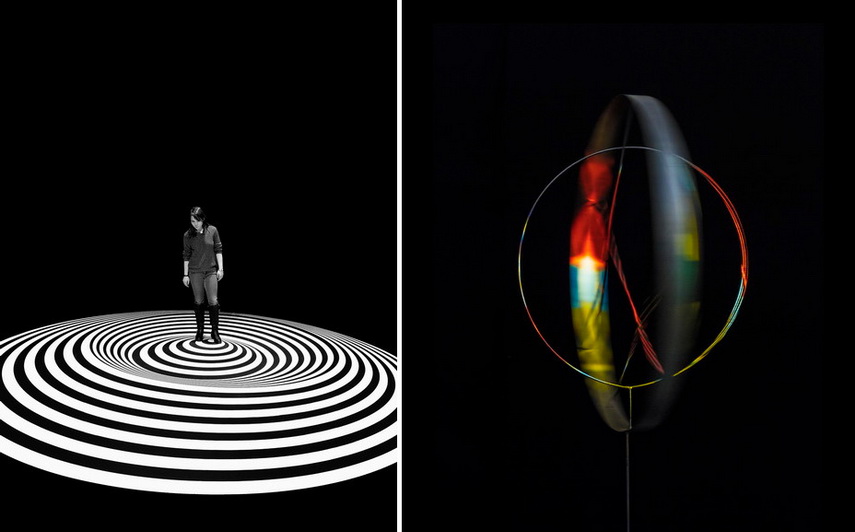

Although it was a progressive movement which embraced various technology-based approaches and outer factors such as psychical presence, participation, and performativity, Op Art was not widely interpreted and presented accordingly. That is why the upcoming exhibition at mumok titled Vertigo. Op Art and a History of Deception 1520—1970 will be the first extensive survey in the recent period to unravel various artistic approaches which explored the optical including paintings, reliefs, kinetic objects, immersive installations, as well as film and computer-generated or computer-controlled art.

The Exhibition Concept

The curators Eva Badura-Triska and Markus Wörgötter decided to name the exhibition after Alfred Hitchcock’s iconic film of the same name made in 1958. Namely, the term “vertigo” is quite ambiguous and it indicates both a physical phenomenon and a matter of sensory and cognitive deception. The film became crucial in the context of cinematic history for numerous reasons; however, it is best known for the “Vertigo effect” used in a key scene in which the leading character climbs the spiral staircase leading and is drawn downwards in a dizzying spiral. This effect, as well as the film’s opening credits, were the work of the designer Saul Bass and the animation artist James Whitney, who was a pioneer of experimental film and animation techniques (his works will be on display).

On the other hand, the curators were very influenced by the theoretical interpretation of Umberto Eco; the famous writer claimed in his 1962 book Opera Aperta that viewers should be active participants in the constitution of artworks, and that same year he wrote Arte programmata, one of the first texts devoted to Op art.

The Lasting Fascination With Deception Phenomenon

The upcoming exhibition will encompass a range of works made throughout the centuries, so the examples of anti-classical art from the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries will be contrasted with the works made by avant-garde masters of the first half of the twentieth century as well as the proponents of Op art from the 1960s and 1970s.

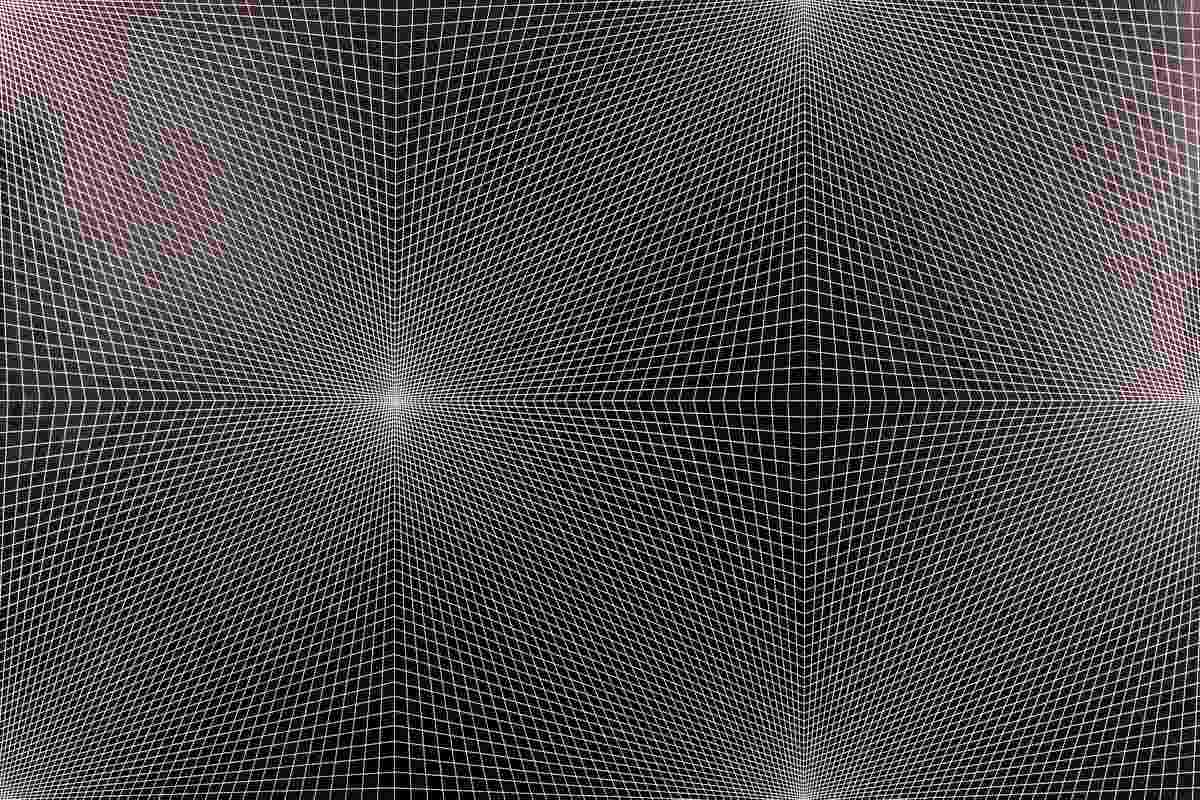

All of the works will show how those artists explored the matters of perception, and an array of vibrating patterns, pulsating afterimages, paradoxical spatial illusions, and other methods of optical illusion and physical influences. Op Art and its close cousin Kinetic art forms were based on participation and interaction which made them contemporary and quite radical, because of the agenda of breaking away with modernist tradition.

Vertigo and Op Art at Mumok

This exhibition is made possible in cooperation with Kunstmuseum Stuttgart, where it will be shown in late 2019, and it will be accompanied by an extensive illustrated catalog including a selection of essays written by the curators and distinguished scholars.

Vertigo. Op Art and a History of Deception 1520—1970 will be on display at mumok in Vienna from 25 May until 26 October 2019.

Featured image: Richard Anuszkiewicz – Convex & Concave, 1966. Acrylic on canvas, 162,9 x 274,3 cm. Courtesy D. Wigmore Fine Art, Inc., New York © Bildrecht Wien, 2019. All images courtesy mumok.

[ad_2]

Source link