[ad_1]

NEW YORK ― The wall was covered in vaginas, or, at least, slang terms for them. “Dirty Plotte” and “Sweet Little C**t” appeared in projections all across the Pratt Institute classroom where comic legend Julie Doucet was preparing to speak. (“Plotte,” for the non-Canadians in the room, is what Quebecers like Doucet call the vag.)

The genitalia references didn’t seem to faze two young nearly identical sisters seated in the audience next to me. While they waited eagerly for Doucet to emerge, the elder sibling fiddled on her iPhone, and the younger one sketched a unicorn in a hot pink spiral notebook. “It’s about a girl who gets in trouble for seeing a unicorn,” she explained.

There was a time when no one thought of Doucet as a role model for young people ― least of all herself. When she started her series of semiautobiographical comics, “Dirty Plotte,” in 1988, her work was so profane and repulsive, feminist bookstores wouldn’t touch it. Critics were vexed by her hefty appetite for violence and gore, which targeted women as much as men.

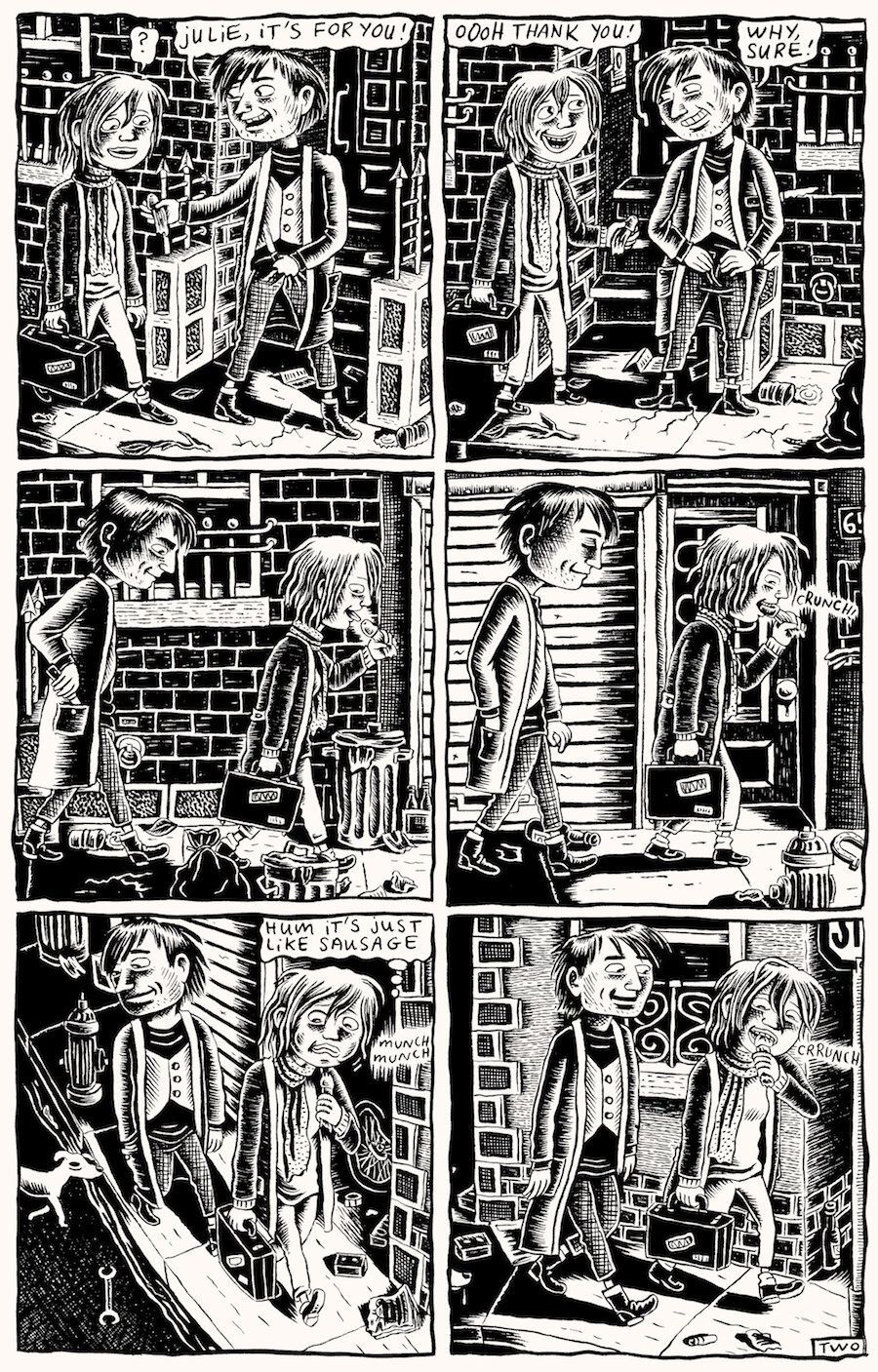

In one her more memorable strips, a cartoon version of Julie is drinking street beers with her pen pal when he chops off his penis and hands it to her like a bouquet of flowers. “Hum it’s just like sausage,” she says after chomping down on its meat. In another, Julie recounts a dream in which she masturbates with a cookie. In a third, Julie’s enjoying a leisurely stroll through a park when a businessman attacks her and slits her open from throat to waist. A dog eventually slurps up her insides.

“I wasn’t a woman like they wanted,” Doucet told the crowd, the “they” referring to the feminist community prominent at the beginning of her career.

Thirty years after her debut, however, she was surrounded by people who wanted her ― by comic nerds in thick-framed glasses, tatted-up millennial women and a sprinkling of kids doodling in their seats. Over the years, she has become a legend in the niche community of underground comics, and the afternoon’s gathering was proof.

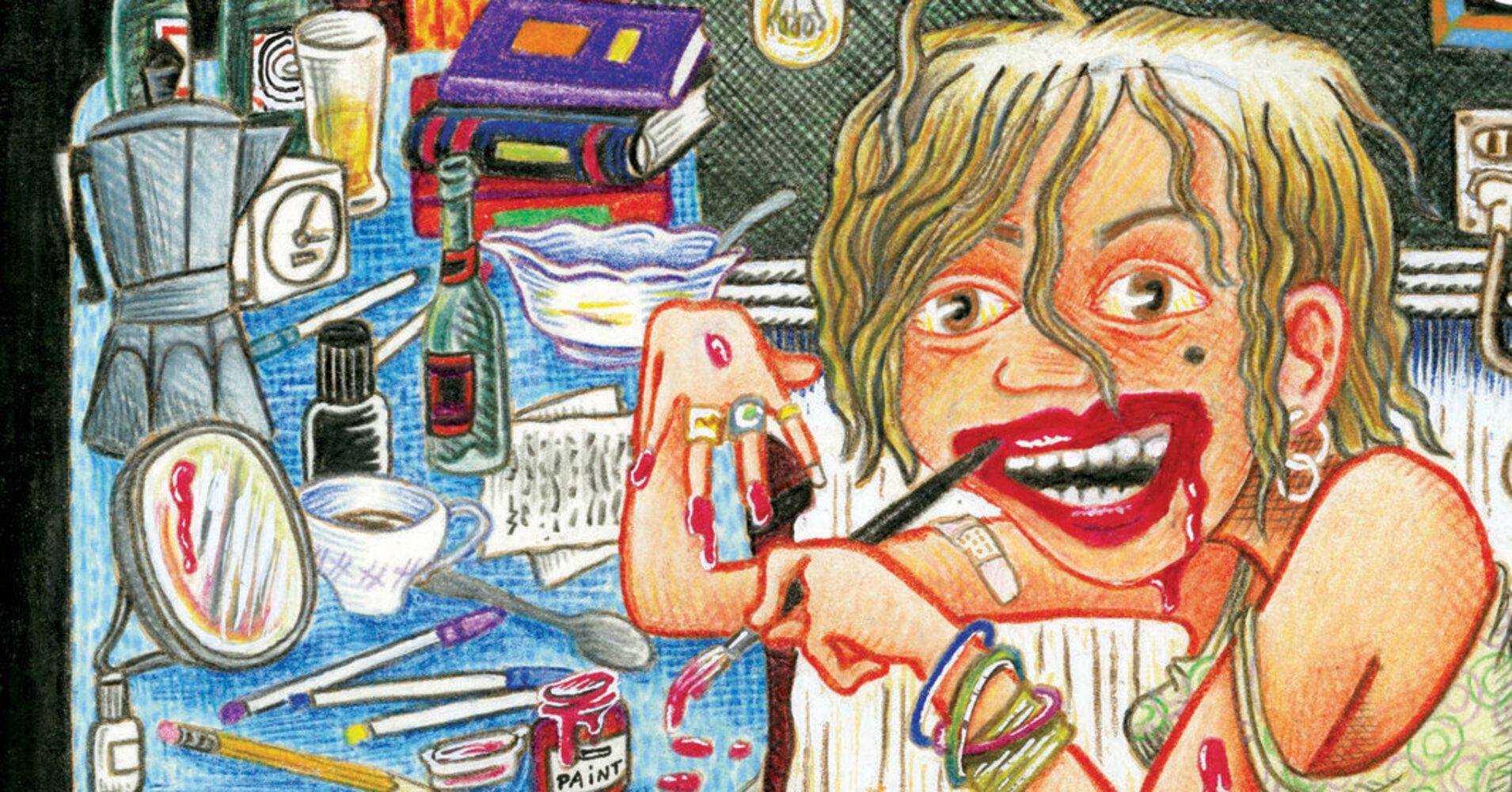

The crowd had gathered to celebrate the new book Dirty Plotte: The Complete Julie Doucet, a compilation of her drawings made from 1988 to 1998, accompanied by essays, interviews and testimonials from fans and friends. When Doucet finally addressed the crowd, the audience arched collectively forward, teetering on the edge of seats not only to get a closer look at the comic mastermind but also, more practically, to hear her. The artist who castrates, menstruates, self-mutilates and masturbates with reckless abandon on the page is incredibly shy in person.

She speaks in a honeyed whisper, her cheeks caught in a state of perpetual blushing. During her interview with critic Anne Elizabeth Moore, the author of the biography Sweet Little Cunt offered little more than big smiles and barely audible snippets of sentences. “Let’s talk about menstruation,” Moore said, starting the talk off with one of Doucet’s favorite subjects for drawings. “What is there to say?” she responded innocently.

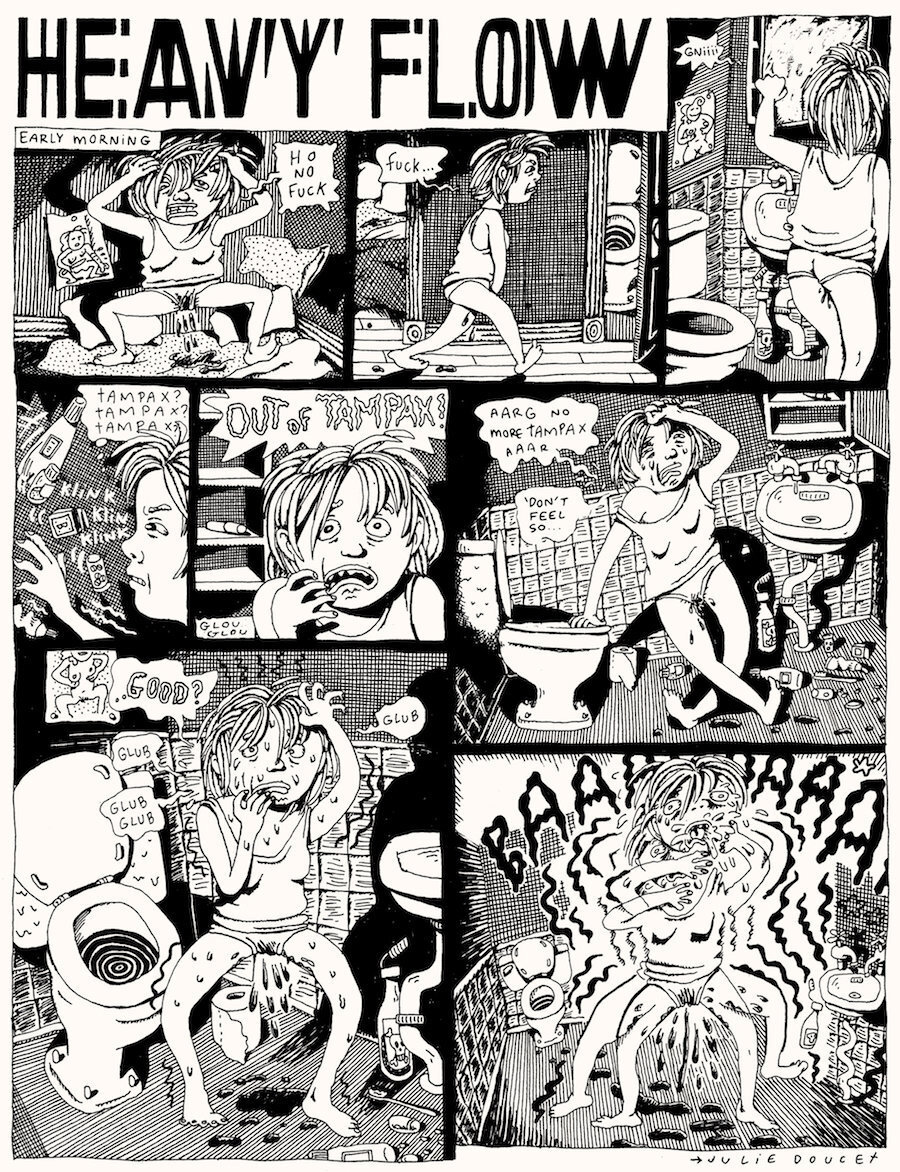

At that moment, a projection of one of her comics, titled “Heavy Flow,” appeared on the wall over her head. Created in 1989, if features Julie squatting atop her bed as the stain between her legs starts to leak through her underwear onto the sheets. “Ho no fuck … fuck,” the cartoon exclaims, the figure tugging frantically on her hair and clutching her crotch in a futile attempt to catch errant dribbles.

A few panels later, a supersized Julie is hulking through New York City like Godzilla riding the crimson wave. Snot and spit spew from every possible hole as black blood gushes like lava from her crotch. It is one of the most graphic, grotesque and accurate depictions of a gnarly period I’ve ever seen. Below this triumphant vision of female monstrosity ― a glorious middle finger to the woo-woo rhetoric of moon cycles and goddess flows ― Doucet sat quietly, her smile communicating naiveté more than mischief.

Born in 1965, Doucet grew up in an upper-middle-class suburb outside Montreal. A fearless tomboy who loved to draw, she said she felt more comfortable in the company of boys at the time than the crowds of her all-girls Catholic high school.

She began making comics as a college student at the University of Quebec at Montreal, quickly identifying bodily functions as her muse. Menstruating was “inspirational,” she said. It packs pure visual force in her panels, a splash of red across the otherwise mundane happenings of everyday life.

Doucet didn’t think anyone would ever see her work at first, so she amused herself by conjuring the wackiest, lewdest stories her imagination could muster. Totally uncensored, she recognized no limits or taboos. Her methods were “compulsive,” she explained. “I didn’t think I was communicating with other women. It was about myself.”

Her very first published comic was for a student anthology in 1986. In it, a character named Dulie Joucet strips down naked, hacks off her breasts and slices open her belly ― a play on the artist showing her guts. Shortly after that, Doucet dropped out of school and went on welfare, determined to focus on making more comics and showing them to whoever was willing to look. In 1988 she drew the first edition of “Dirty Plotte,” a stapled storm of fever dreams that ran every month in Factsheet Five, a sort of zine culture directory famous in the 1980s and early ’90.

At the time, the underground comic scene was predominantly male, with an anything-goes attitude that elevated mostly heterosexual male fantasies. (Think: Robert Crumb, Jack Jackson.) But there was a small contingent of influential female voices, including Aline Kominsky-Crumb, who eventually noticed Doucet’s work and asked her to contribute to the anthologies Wimmen’s Comix and Weirdo. Like Doucet, Kominsky-Crumb is well known for recounting the most intimate, sordid and sometimes humiliating details of her life in images. Doucet might have initially considered herself deviant, but she was beginning to realize that other women sought to commit the same sorts of social violations she did.

In 1989 Doucet began publishing “Dirty Plotte” with publisher Drawn + Quarterly (the company also responsible for her 2018 book), and the fan letters rolled in. Readers ― women and men ― thanked Doucet for vocalizing thoughts and experiences they’d long kept silent, so she started publishing their testimonials alongside her work.

“I really love your comic books,” wrote Jessica. “So much so, in fact, that I wanted to write you and tell you what my penis is named. Except, I don’t have one (a penis).”

“My god this shit’s disturbing,” a fan named Rob wrote, “but then again, that’s probably why I like it so much.”

Doucet also invited readers to send her appropriately NSFW goodies: dick pics, photos of tattoos, images of themselves she could then maim and dismember on the page. An Australian fan named Robert sent a paper-doll-type drawing of himself in glasses and nothing else. A hatchet, saw and various knives floated around him. Dotted lines suggested the best places to operate. “I never could draw hands and feet,” he wrote. “(cut em off.)”

Unsurprisingly, the fan letters got weird. “I like your mag because you look like my sister,” one reader said. Another begged her to castrate him before he masturbated on her drawings again.

It was the unfortunate nerd-bro tenor of the comic scene that led Doucet to quit comics in 2006. “I was quite sick of the crowd, the all-men’s crowd,” she told Vulture this year. “Men tend to be very obsessive about comics and not be interested in anything else but comics. That drove me crazy.” Since, she has dabbled in other art forms, from collage to short film, but never returned to her signature medium. She would return to comics, she told me, only if she had something new to say.

A lot has changed since she joined and then left the underground scene of the ’80s and ’90s. Her penchant for ugly truths and uglier fantasies, which once made her a pariah in feminist circles, is now considered a superhuman strength. Shameless in the best of ways, Doucet demonstrates how one person’s vulnerability and vulgarity, more often confined to bedrooms and diaries than projected to crowds, can be a beacon of mutual support when experienced in the open. Even her introversion has a defiant streak, the perfect polar opposite of her spare-no-detail drawings. She always expresses precisely what she wants to — no more, no less.

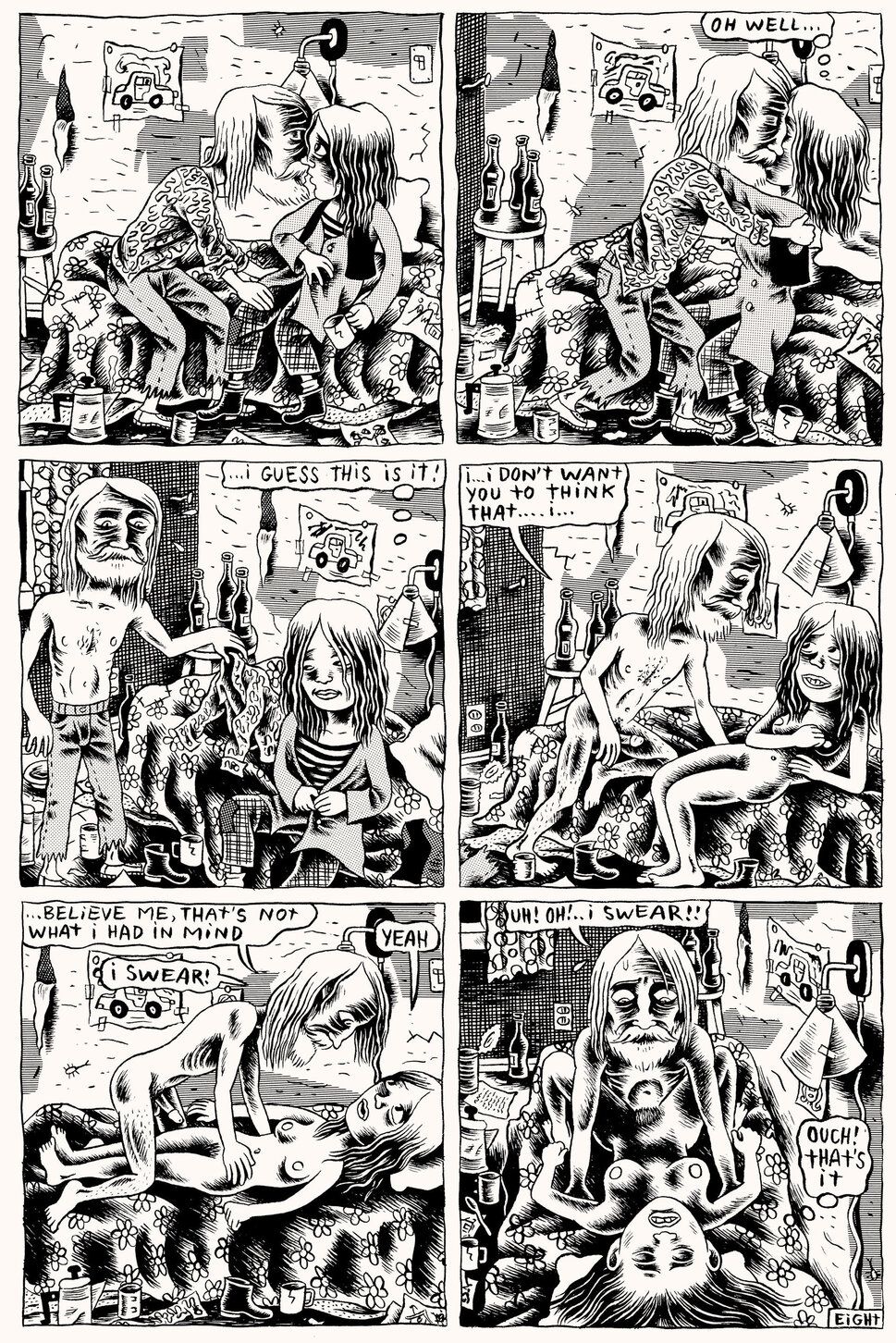

Of all the nasty shit Doucet has put on paper, there’s only one comic she has ever regretted, she said. It’s called “My First Time,” from 1993, detailing the not-so-special way she lost her virginity to a scraggly, older artist. “I guess this is it!” 17-year-old Julie thinks as the man pumps into her until he comes. She, unsurprisingly, does not. Doucet, who described the sex as “sad and humiliating,” said that in retrospect, it was too personal to put in print.

After she relayed the regret to the audience at Pratt, a 20-something stood up. “So many women have had experiences like that,” she said forcefully. “Thank you for calling his behavior out.”

“OK,” Doucet said with a modest smile.

HuffPost’s “Her Stories” newsletter brings you even more reporting from around the world on the important issues affecting women. Sign up for it here.

REAL LIFE. REAL NEWS. REAL VOICES.

Help us tell more of the stories that matter from voices that too often remain unheard.

[ad_2]

Source link