[ad_1]

John Akomfrah, Vertigo Sea (still), 2015, three-channel HD video installation, 7.1 sound, color, 48 minutes, 30 seconds.

©SMOKING DOGS FILMS/COURTESY LISSON GALLERY

‘No man is an island,” John Donne wrote. Almost 500 years later that is still the case. Everyone and everything is connected today—by the internet, by migrations, and by a bunch of other forces, some of which are hard to see. Maybe it’s not surprising, then, that islands are a recurring element in John Akomfrah’s show at the New Museum in New York, “Signs of Empire” (on view through September 2), which focuses on the many, many ways disparate peoples and places are bound to one another. Despite Akomfrah’s looming influence on a younger generation of artists depicting interwoven histories and identities, this exhibition, curated by Gary Carrion-Murayari and Massimiliano Gioni, is somehow the first-ever survey to be held at a U.S. museum for the Ghanaian-British artist. It’s nearly a perfect show—its only problem being that, with just four video installations on view, it’s far too small to do a pioneer like Akomfrah justice.

The quartet of works—three produced by the artist working solo, the fourth made during the 1980s as a member of the now-defunct Black Audio Film Collective—acts as a good sampler of Akomfrah’s output. Included are ruminations on the legacies of colonialism, climate change, cultural theorists, and historical events, which are either imaginatively restaged (often in very abstract terms) through lush cinematography or represented through carefully cobbled-together archival footage. It’s tough work, in some ways—slow in its pace, dense in its piled-on allusions—but it’s hard not to be hypnotized by it.

Akomfrah’s style finds its equivalent in the visual poetry of Terrence Malick and the chilliness of Andrei Tarkovsky, though unlike both of those directors’ films, Akomfrah’s work has an outwardly political dimension. In its toss-up of timelines and semi-fictional narratives, his videos reflect the experience of a life lived in constant motion, at a time when people are always shifting from place to place. That state, in which people’s identities are also rarely ever stable, is something depicted by Akomfrah, who was born in 1957 in Accra, Ghana, and raised in London.

John Akomfrah, The Unfinished Conversation, 2012, three-channel HD video installation, 7.1 sound, color, 45 minutes, 48 seconds. Installation view.

©SMOKING DOGS FILMS/COURTESY LISSON GALLERY

The most exemplary work in the show is The Unfinished Conversation (2012), a three-screen installation about Stuart Hall, the late Jamaican-born cultural theorist who believed that history was formed by crisscrossing narratives shared by various communities. Though Akomfrah’s installation is, more or less, a biopic, it is not linear—the past, present, and future seem to happen simultaneously. And because Hall spent his entire life in motion, the images, identities, people, and places in the installation are constantly in flux.

Akomfrah lends these concerns an appropriately epic scale. In the 2015 three-screen installation Vertigo Sea, his focus is Earth as a whole, in particular its oceans. He uses the sea as a metaphor for interconnectivity, juxtaposing footage culled from the 2001 documentary series The Blue Planet with images of whales being gutted, their maroon-colored flesh spilling out onto docks. In between these pictures of sun-speckled waters and translucent jellyfish, he includes shots of his own creation, of a figure garbed in what appears to be a colonial European outfit. Often filmed from behind and looking out onto the ocean, as though he were taken straight out of a Caspar David Friedrich painting, this person, eagle-eyed viewers may note, is Olaudah Equiano, who, after being sold into slavery during the 18th century, bought his own freedom and went on to become one of the most prominent abolitionists in Britain. Viewing Akomfrah’s film, one wonders: Where is he? When is he?

Adrian Piper, Food for the Spirit #8 (detail), 1971/97, 14 gelatin silver prints.

©ADRIAN PIPER RESEARCH ARCHIVE FOUNDATION BERLIN/PHOTO: JONATHAN MUZIKAR/THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NEW YORK, THE FAMILY OF MAN FUND

At the Museum of Modern Art, an Adrian Piper retrospective—long-overdue, years in the making, and, with more than 290 works, appropriately oversized—laid bare the ongoing effects of structural racism, sexism, and xenophobia in America. (The show, which closed last month, travels next to the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles, whose chief curator, Connie Butler, organized it with Tessa Ferreyros and MoMA’s Christophe Cherix and David Platzker.) Rarely ever does Piper allude to specific happenings in her video installations and photographs, which were given prime placement in the show. But today’s—and yesterday’s—police shootings, harassment, and lynchings are never too far away from what’s depicted in her work, even if, in some strange way, her pieces feel timeless, as though they could be presented at any moment, by any institution, and still feel contemporary.

Take her 1988 video installation Cornered, in which Piper, dressed like a talking head in a documentary, tells viewers that her ancestors were called “house niggers” and raped by their masters. If the viewer is American, she says, theirs might have been, too, meaning that the viewer also might be black, according to the “one-drop” rule, which states that a person is black if anyone in their ancestry, no matter how far back, was identified as such. Her image appears via a video displayed on a monitor behind a table, flipped as if by the hands of an enraged spectator. This piece seems to propose that slavery—long considered to have ended in the United States during the 19th century—may be invisible to many Americans (white ones, in particular) today, though its effects can still be felt.

Not all of Piper’s work is as explicitly political. A good deal of space was given over to her Conceptualist and Minimalist gestures from the 1960s and ’70s, which utilize the language of those in power in a much different way—through text, written according to idiosyncratic sets of rules. (One example is Concrete Infinity 6-inch Square [“This square should be read as a whole . . .”], 1968, which features a small piece of paper that has the bracketed portion of its title typewritten onto it, along with text that notes the various ways one can read this work—“from upper left to upper right to lower right to lower left or upper left to upper right to lower left to lower right” and so on and so forth.) But it is Piper’s video- and photo-based work that remains her greatest output, perhaps because these pieces attack the viewer, visually. They feature sitters who stare directly into the camera’s eye, as if to send viewers into a fight or flight response.

Adrian Piper, What It’s Like, What It Is #3, 1991, video (color, sound), constructed wood environment, four monitors, mirrors, and lighting. Installation view in “Dislocations,” at Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1991–92.

©ADRIAN PIPER RESEARCH ARCHIVE FOUNDATION BERLIN/THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, ACQUIRED IN PART THROUGH THE GENEROSITY OF LONTI EBERS, MARIE-JOSÉE AND HENRY KRAVIS, CANDACE KING WEIR, AND LÉVY GORVY GALLERY, AND SUPPORT FROM THE MODERN WOMEN’S FUND

Sometimes, Piper is explicit about which historical events haunt her work. For the installation Black Box/White Cube (1995), she appropriates a news broadcast about the beating of Rodney King by LAPD officers, and for a series of large photographs, Piper overlays text onto an image of Anita Hill—the law professor who accused Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas of sexual harassment—as a child. The thread, in both works, is the abuse of power—a topic that could not possibly be timelier.

Interestingly, Piper has translated these concerns for our digital age. In 2012, for a piece called Thwarted Projects, Dashed Hopes, A Moment of Embarrassment, Piper, who has long identified as black, swore off her racial identity for a new one. The work exists in the form of a digital file, and it features a headshot of the artist in which her skin appears to have been tinged an unnatural purple. In a note accompanying this discomfiting image, she writes that she now identifies as “6.25% grey.” This transition into the digital realm is an interesting one—it shows that Piper’s concerns about the ways one’s identity is made visible to the public are still relevant, if not even more so than before, now that it’s easy to research a person’s race or gender through some quick Googling (which can sometimes lead to false results). She concludes the work with a message of self-affirmation: “Please join me in celebrating this exciting new adventure in pointless administrative precision and futile institutional control!”

Liz Magic Laser, Primal Speech, 2016, mixed-media installation with single-channel video.

COURTESY THE ARTIST AND METRO PICTURES

I couldn’t help but think of Piper’s fourth-wall-breaking video installations when I came across Liz Magic Laser’s own, Primal Speech (2016), which was included in the excellent Josh Kline–curated group show “Evidence” at Metro Pictures this summer. In this work, inset in a padded wall and displayed in front of a gray mat, a group of men and women spew hatred at the camera, alluding in the process to issues like Brexit and the refugee crisis. “It’s all about you,” one white man says, “it’s not about us, it’s about you.” A woman appears occasionally, looks directly into the camera’s lens, and says that the viewer is powerless. Eventually, we realize that these people are all in the same mental asylum–like space, crying, screaming, and shouting. They never once acknowledge one another.

“Evidence” was a powerful attempt to visualize some of the racism, sexism, and economic inequalities that are so often experienced in this Trump-dominated America. The videos, sculptures, and photographs on view reflected the anxiety felt in the U.S. and Europe since 2016, though never once did they mention the American President or, for the most part, any specific historical events.

Kline himself addressed economic inequities with a group of works about the service industry, with the words “I <3 my job!”—presumably borrowed from one waiter’s nametag—appearing on a 3-D-printed dinner roll in one piece. Paul Pfeiffer shared Kline’s concerns about exploitation and economic struggle in two videos that recycle game show footage, altered via digital effects so that the images have been scrubbed clean of any dollar signs or numbers. We know the smiley contestants are waiting to be told about their winnings (or lack thereof), but because of the way Pfeiffer presents these images, they just look lost amid a series of flashing lights and mod design elements. The price may be right, but the mood is all wrong.

“74 million million million tons,” a group show at SculptureCenter curated by Ruba Katrib (who has since departed for MoMA PS1) and artist Lawrence Abu Hamdan that closed earlier this month, had thematic overlaps with “Evidence.” In the exhibition’s catalogue, they describe a frustration with the directions taken by many artists today working with research, which they find overly academic and largely inaccessible. They instead assembled a group of artists whose work is less data-oriented—there are few diagrams or sets of information included in the show’s works.

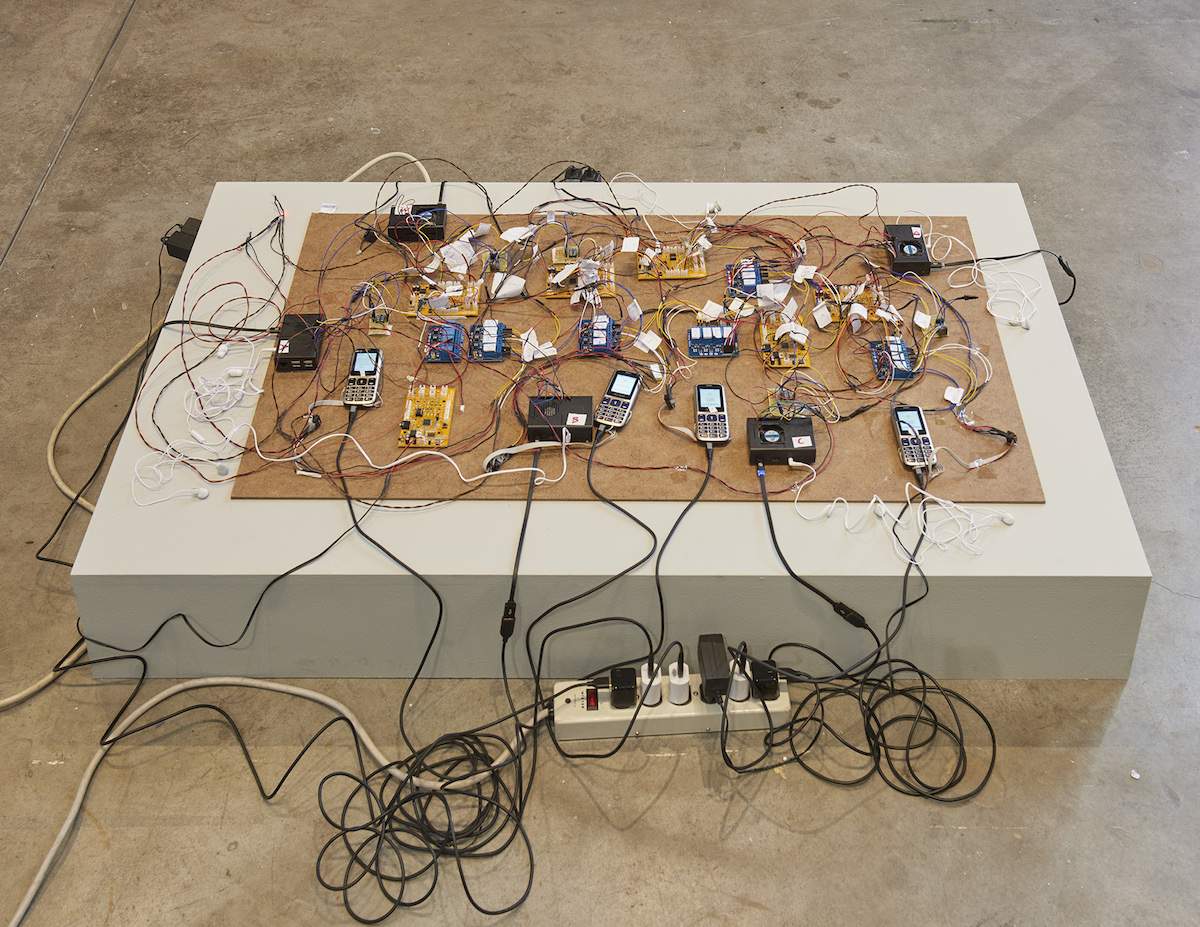

Shadi Habib Allah, Did you see me this time, with your own eyes?, 2018, Raspberry Pi computers, Z-Line phones and chargers, microcontrollers, video with sound. Installation view.

COURTESY THE ARTIST; GREEN ART GALLERY, DUBAI; RODEO, LONDON; AND REENA SPAULINGS FINE ART, NEW YORK

A good example of the work they favor is Sidsel Meineche Hansen’s EVA v3.0: No right way 2 cum (Oculus Rift), 2015, a minute-long VR piece in which the viewer is made to watch a digital version of a woman masturbating and then, in extreme close-up, ejaculating. This disturbing piece, which came complete with a booming score, is clearly based on the form of contemporary pornography, and it reflects how misogyny and objectification finds its way into entertainment. (The avatar Meineche Hansen purchased to produce the work was made by a man, and with its close-ups of computer-generated female anatomy, EVA v3.0 seems to allude to his gaze.)

Sean Raspet and his company Nonfood supplied algae-based nutrition bars, made available to viewers in a shiny vending machine for $4, that draw on a familiarity with the sheen of corporate offices, and George Awde created semi-erotic images of men in Lebanon that imply a covert network or community. In all these cases, research was implied rather than outright stated.

Katrib and Abu Hamdan’s show was open-ended, in ways that were likely to please some and frustrate others. For me, it was a compelling look at the ways that one event can trigger happenings around the world. The suggestion, it seemed, was that everything is connected—an idea visualized by Shadi Habib Allah’s installation Did you see me this time, with your own eyes? (2018), wherein flip-phones are connected by circuitry, their wiring and chargers crisscrossing on a low pedestal. A booklet accompanying the show tells us that the phones are the same kind as those used by Bedouin smugglers, who communicate via slow-speed 2G networks that are tough to trace, and that all of Habib Allah’s gadgets are actually connected. In SculptureCenter’s quiet, cavernous space, the phones appeared to hum with life, and in order to survive, they must be linked together.

[ad_2]

Source link