[ad_1]

When I was little, I used to read the last page of a book before I bought it. I’d walk through my school’s book fair and grab a title whose cover drew me in. Then I’d slyly flip to the last chapter, scanning it for evidence that it was a safe enough story, one with a happy ending I could invest in. This habit was strategic. It was a way to alleviate anxiety ― to reassure myself that the main character ended up (at least mostly) all right, or prepare myself for the tragedy that was to come.

Unfortunately, that’s impossible to do with your own life.

Being a single woman over the age of 30 ― I am single, childfree and nearly 31 ― feels like living an unfinished story. It’s both exciting in its seemingly endless possibilities and terrifying because a “happy ending” for women has long been synonymous with a romantic partner and a baby.

At times, my un-partnered, childfree life feels near triumphant. I am a professional writer, as I long wanted to be. I live in an adorable apartment in Brooklyn with a friend of more than 20 years. I have a robust community of close, loving friends, and too many invitations to weddings, bridal showers, engagements, baby showers and bachelorette parties to keep up with. I have a moderate amount of disposable income, and since I don’t have children or a partner to support, all of that disposable income can be put toward things I want to do: travel, the occasional impulse purchase, dinners out in one of the best food cities in the world.

By all accounts, I am extremely lucky.

As MacNicol outlines, there are few roadmaps for or stories about women with lives like hers ― lives like mine. And the stories that do exist nearly always treat those aforementioned realities (no kids, no husband) as sad, something to be overcome and fixed by a story’s last page.

And yet, as I move past 30 and more solidly into my 30-something decade, there are big question marks. Can I ever afford to live alone? Is buying an apartment a supremely stupid thing to do? Will I ever get married? Do I want to have children? If I do, what steps should I be taking to ensure I can if I don’t meet that long-term person before time runs out? Are these even the most important questions to be asking of myself in the first place?

More broadly, what does a “happy ending” look like without marriage and children? What does a life well lived look like past a certain age, when those two things aren’t even goals?

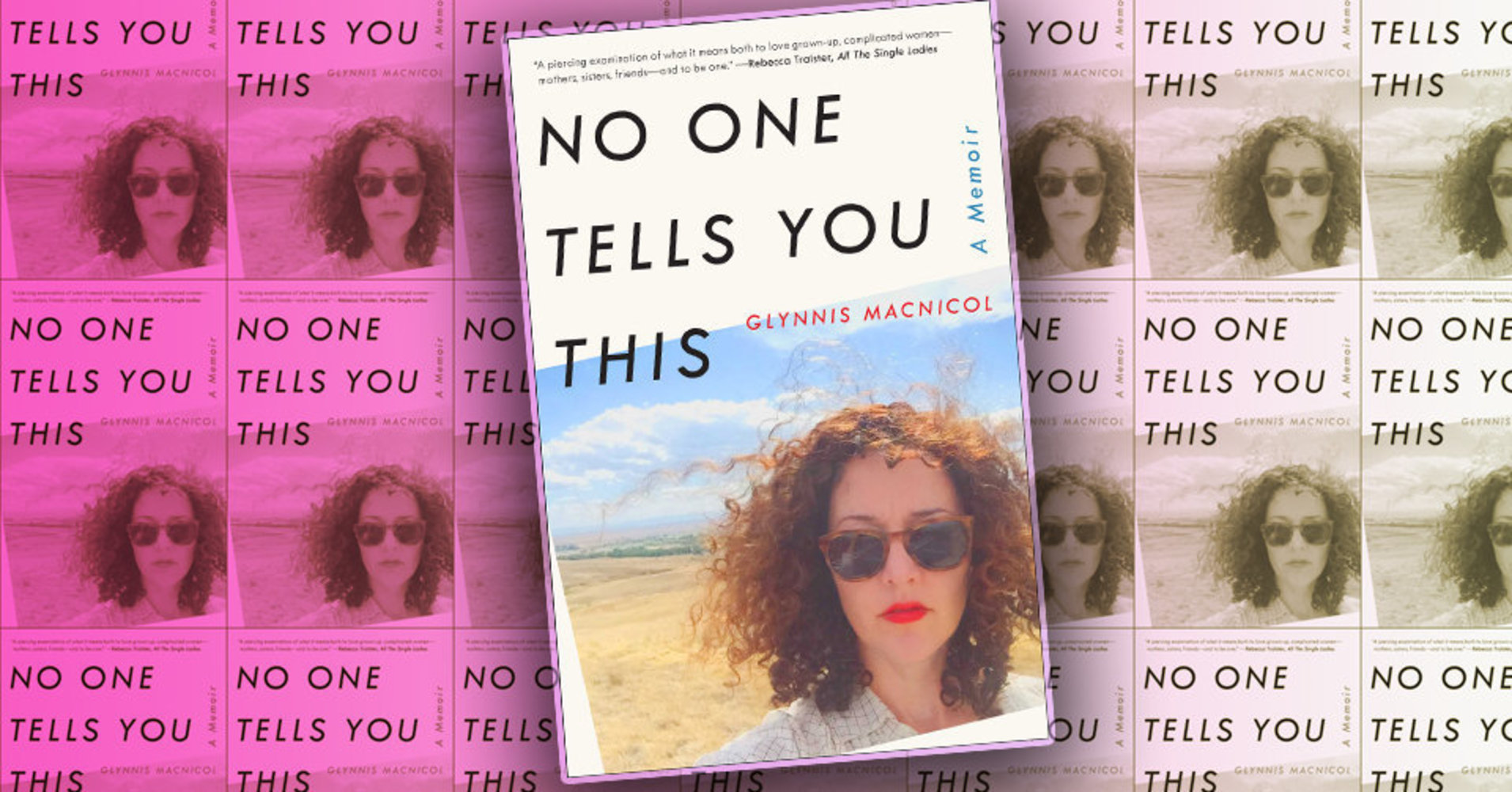

These are some of the Very Big questions that writer Glynnis MacNicol eloquently dives into in her new memoir, No One Tells You This.

MacNicol used her 40th year on earth to explore what it looks like to be a successful, single, childfree woman of a certain age, the kind of woman whose life “had officially become the wrong answer to the question of what made a woman’s life worth living.” As MacNicol outlines, there are few roadmaps for or stories about women with lives like hers ― lives like mine. And the stories that do exist nearly always treat those aforementioned realities (no kids, no husband) as sad, something to be overcome and fixed by a story’s last page.

“Sad Single Lady Betters Herself And Finds The Hot Sensitive Guy of Her Dreams” is a rom-com and romance novel trope for the ages. “Happy Single Lady Who Has Struggles And Dreams And Romances And Insecurities And Satisfying Life Experiences But Stays A Happy Single Lady” is a less familiar narrative.

But demographically, it’s a story that many millennial and Gen X women share. In 1960, nearly 60 percent of Americans between the ages of 18 and 29 were married. By 2011, that percentage had fallen to just 20. American women are marrying and having kids later, or not at all. We are a force ― professionally, politically and socially. Our narratives should be a force as well.

MacNicol’s memoir is not a rah-rah-I-don’t-need-a-man-so-fuck-you type of book. Instead, it’s something better ― it’s honest. The first chapter opens on the eve of MacNicol’s 40th birthday, a milestone women are implicitly told marks a stark dividing line, a moment when, as MacNicol puts it, “all that was good and interesting about me, that made me a person worthy of attention, considered by the world to be full of potential, would be stripped away.” Instead of throwing herself a party or a descending into depression, MacNicol chooses a brief escape. She turns off her phone, takes the train out to New York City’s Rockaway Beach and gets a room for the night at a recently opened hipster motel. If she’s gonna enter her 40s “alone,” why not be on a beach. By the morning, she wakes up “feeling victorious.”

The rest of the book largely focuses on the following year. We join her in Toronto where she goes to help her pregnant sister and care for her mother who has Parkinson’s, as she flies off on a last-minute press trip to Iceland, and as she goes back and forth to a ranch full of opportunities for self-discovery in Wyoming. Readers also get to spend a lot of time immersing themselves in MacNicol’s beautiful, full, hard, happy life in New York. These anecdotes provide a framework through which MacNicol can reflect on the thrills and hardships of living a life for which modern women have few models.

MacNicol acknowledges the negatives that can come along with a solo (not solitary, but solo) life in a society that assumes those circumstances make you fundamentally unhappy. She communicates the exhaustion of doing physical and emotional caretaking for her mother and her friends without a designated person to lean on for support. She also recounts the unintentionally condescending comments people make when they want to assure her “there’s still time” to find a man. She explores the often unnamed mixed feelings that can arise when watching the friends you’ve built an adult life with get married ― deep happiness for those you love, but also an understanding that “it was hard work to root yourself so deeply in life that you could still love people and rely on them, knowing that any point they could make decisions that would leave you scrambling to find solid ground again.”

In a world that constantly pits women against each other and shoves us into archetypal boxes, MacNicol’s ability to express the thoughts that mirror my own while resisting simplified caricatures feels like a gift. She realizes the moments that might be simpler if she had a partner to lean on, and also honors the genuine wistfulness some of her friends with partners have when they talk about her life. Because ― surprise! ― marriage and babies don’t make life easy, just different. That’s something you understand more clearly the closer you are to people who have chosen those wonderful, life-altering things. Part of being human is to imagine the freedoms and luxuries of lives that are not your own.

As MacNicol points out, nearly every woman she knows “seemed to think she was failing in some way, had been raised to believe she was lacking and someone else was doing it better.”

Even better than having a fabulous life is having a life that you actively choose.

Ten years behind MacNicol in age, I see echoes of my life in her own. She’s a writer and author. She moved to New York City when she was 23. She’s dated men who are varying degrees of unavailable. She has a tight-knit group of friends whom she depends on and who depend on her. And she’s mostly happy in a world that tells her on a daily basis that she really shouldn’t be. (Of course, MacNicol is a white, straight woman living in a metropolitan city with enough money to live comfortably. Her story is not everyone’s, something she does an effective job of acknowledging and owning.)

Reading No One Tells You This was like a breath of fresh air, an affirmation that if my life continues to be structured as it is now, that might be all right ― fabulous at times, even. And even better than having a fabulous life is having a life that you actively choose.

A friend recently told me her mother believed that to have a marriage you must be willing to accept a divorce. In other words, a long-term relationship should be a thing that you actively choose because you’ve thought about it and want it, not because you are simply trapped in it. The same wisdom applies to a relationship with yourself, a story, and your life as a whole.

“My life, precisely as it was ― the product of good and bad decisions ― began to come into focus for me,” writes MacNicol. “Sitting there, I could see it for the first time as something I’d chosen. Something I’d built intentionally. … Once I began to see it as such, it dawned on me that I had no wish to escape from it. On the contrary: I wanted it.”

[ad_2]

Source link