[ad_1]

Installation view of “Camp: Notes on Fashion.”

COURTESY THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART/BFA.COM/ZACH HILTY

Though it might not have been high in mind for the fashion set, those of a particular art-inclined orientation couldn’t help but wonder, when “Camp: Notes on Fashion” opened at the Metropolitan Museum of Art: might a pair of famous yellow rubber construction boots figure in the exhibition? Alas, it was not to be—though Met director Max Hollein marked his presence all the same.

Before taking up his current station in New York, Hollein proudly wore—and proselytized—big bright yellow boots during his time as director at the Städel Museum in Frankfurt, Germany, where his showy footwear fed a fundraising campaign for new construction. When asked if he attempted to use his sway to work a pair into the Met’s Costume Institute show, however, he could only laugh. “It was a certain camp moment we introduced back then,” Hollein said, “but I stayed away from that.”

Hollein.

EILEEN TRAVELL/COURTESY TEH MET

He did find a lot to like in the show, though, with its mix of more than 250 objects—including artworks to accentuate displays of clothes (and vice-versa) dating back to the 17th century. “The show is really significant because it weaves different narratives into the subject, and we are able to reconsider and revaluate certain objects in our collection through the lens of camp,” Hollein said.

As a subject, “camp” is elusive and—as articulated by curator Andrew Bolton in remarks at the show’s preview—“by its very nature subversive.” In his introductory essay in the exhibition catalogue, Hollein suggests that, by looking through “camp eyes” at the work on view, “Not only will you discover a new way of seeing art, but you will better understand camp’s generosity and magnanimity.”

In the catalogue’s wondrously discursive main essay, “The Spectacles of Camp,” Fabio Cleto writes, “Camp does not make fun of things grave, momentous, and solemn; it makes fun out of them, cherishing them as it transcends their solemnity into irony.” Identifying a phenomenon that cannot be tidily defined, he continues: “Mozart, Dostoevsky, and El Greco are camp. Not so Beethoven, Flaubert, and Rembrandt. How is that so? Oh well. Camp is as much exquisite as this question remains unanswered.” (Not yet two pages into his exegesis, Cleto soon thereafter writes, “Should you feel lost by now, reader, yes, you have a right.” And then another aside: “Even more at a loss, now? Trust me, you had better be.”)

Hollein held forth on the slippery subject, with what seemed like real reverence, in an interview at the Met. “It is an aesthetic, an attitude, a way you can look at the world,” he said. “The exhibition is focused on fashion, but it also shows that just a sheer gesture [or] body posture can be camp as well. It has a performative aspect to it, in how you define yourself toward society, how you define your gender and how you want to express that. For me, the most successful fashion shows touch on broader subjects and are all-embracing. It’s about costumes but many other things as well.”

Installation view of “Camp: Notes on Fashion.”

COURTESY THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART/BFA.COM/ZACH HILTY

Though the glitziest presentation in the show is reserved for a main gallery filled from floor to ceiling with high-flying fashion (a pair of hot pink Balenciaga shoes made to look like high-rise Crocs, a Vaquera dress in the form of a bag from Tiffany & Co., an Ashish sequined shirt bearing the words “You’re much lonelier than you think”), the art along the pathways leading up to it tells a prismatic story about what camp might or might not have meant in the past. The first work to catch a viewer’s eye is a 17th-century bronze statue by Pietro Tacca staring out attitudinally in a body-flaunting contrapposto pose (sure to make certain museum-goers flash on Bruce Nauman). Around it are more contemporary works by Hal Fischer and Robert Mapplethorpe riffing on similar sights, in an era-mixing, style-rhyming manner revisited through the whole of the show.

Installation view of “Camp: Notes on Fashion.”

COURTESY THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART/BFA.COM/ZACH HILTY

“We live in a time where we have very polarized opinions and a certain tendency to think almost digitally—yes, no, left, right,” Hollein said. “I would argue that being able to look at the world in different ways, using irony and different vantage points and turning hierarchies around, is a very healthy way of engaging in conversation these days.”

How might the use of current art and fashion inform the Met’s offerings of work from the past? “It’s an additional lens and an additional way for how you can look at them,” Hollein said. “It opens up a new set of connotations, a new set of connections. Camp as a subject opens up a whole new set of interpretations that bring you on a journey, like a good novel can do. It expands your horizon rather than narrowing it down. I think you would fail if you suddenly see everything only through the camp lens, but it’s very useful to see, however you want to go about that.”

Installation view with Vaquera’s Tiffany & Co. dress.

COURTESY THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART/BFA.COM/ZACH HILTY

How might an exhibition like “Camp” figure in his thinking for the future of the Met, even though the show’s conception predated his arrival as director last fall? “We want to show how cultural developments are interconnected and how our institution—while we present art in a sometimes-departmentalized way—can bring them into a fruitful and interesting dialogue crossing not only centuries but also crossing mediums and perceptions,” Hollein said. “In that way, this show—working with different departments and going from 1650 to now—is a major example of that.”

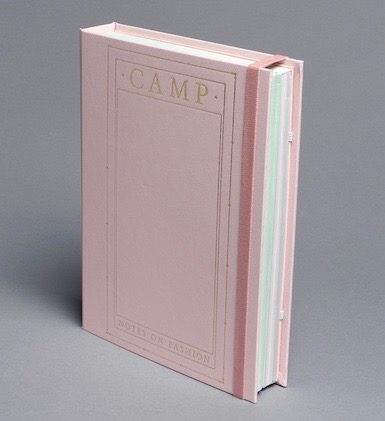

The exhibition’s catalogue.

COURTESY THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART

On the subject of mixing and matching, the director continued: “I think the Met, more than before, will be a strong voice in the cultural discussion of today and finding topics that resonate with us while showing how objects that are sometimes centuries old can inform that. That’s a really important part of what the exhibition achieves and what we will be seeing more of in the future. The Met is unique in the sense that we have an all-embracing perception of what art is and what defines our culture. The Met is not only the most important encyclopedic museum in the world—it also has a Costume Institute, a musical instruments department, arms and armor, and many other things. It shows a broad way of looking at cultural development and art-historical references.”

The Met can get down with glitz, too. “We all love the almost-outrageous interpretations, the way dress codes change and support the idea of gender fluidity and the whole question of not being defined,” Hollein said. “And then of course you’ll find it fascinating to embrace or re-embrace popular figures and put them into this context, like Liberace or Cher. It’s great to have their dresses here in the show.”

[ad_2]

Source link