[ad_1]

It’s a week before her wedding when a bride’s dead grandmother visits her in the form of a ghostly parakeet and asks her what the internet is. It’s the last question her grandmother had asked her, shortly before falling from a roof and dying 10 years ago. At the time, she had lied, telling her grandmother that “its effect on society would be nominal.” This time, she tries to tell the truth.

“People use it to promote themselves like brands,” she says. “Because everyone is famous, no one is.” She tells her grandmother, “When you can see anyone at any hour, it collapses perspective and time. Add to that the isolation and distance from which most people observe, and the Internet gives the impression that one person is simultaneously having a party, turning fifty, scuba diving, baking with a great aunt.”

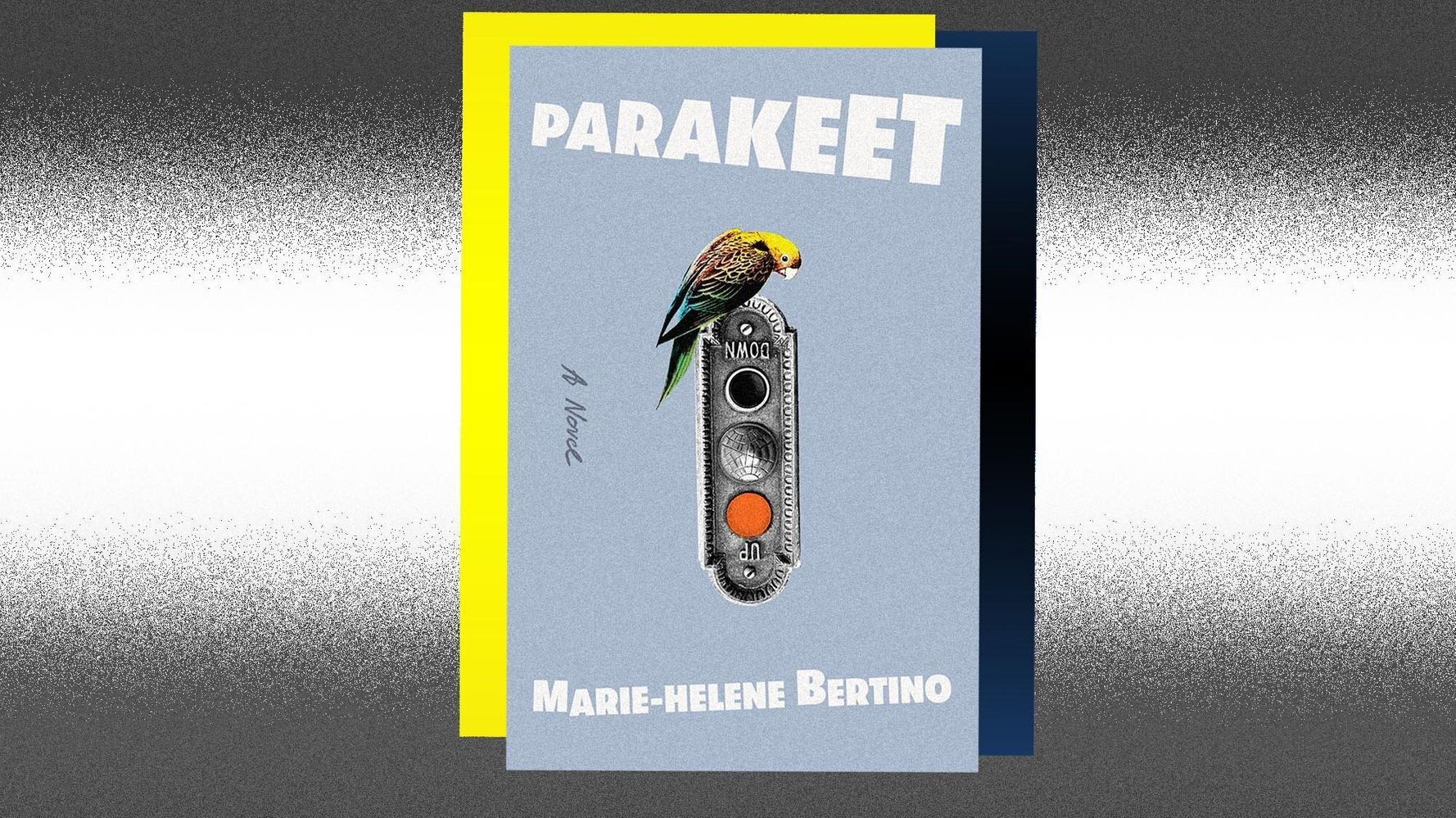

Marie-Helene Bertino’s dazzling new novel, “Parakeet,” which follows the bride in the week leading up to her wedding, often feels that way, too: Time and perspective wobble and give way. Of the internet’s chaos, the grandmother replies, “Sounds like a giant panic attack.” In Bertino’s hands, the effect is less panic and more woozy wonder, a simultaneously hilarious and gutting exploration of trauma, loss and displacement.

As the woman counts down the final week of her single life, she repeatedly confronts the pain in her past ― from her mother’s mundane cruelty to being violently attacked years before ― and the way these ruptures have made her world feel slippery and fragmented. Her groom sends her early to the wedding hotel, “to ‘decompress’ because ‘of late’ I’ve become a bit of a ‘nightmare.’ To break apart, if necessary, but to do so properly, amid slatted pool chairs and conference coffee.”

“Parakeet” asks how we reconstruct a personal geography after trauma, how we assemble those elusive fragments into a coherent self, situated in a coherent timeline, a coherent set of relationships.

The parakeet hasn’t just visited to get a tech update from her granddaughter. She’s also visited to ask the bride to reconnect with her brother, from whom she’s been estranged ever since a scene at his own disastrous wedding years before ― and to cover the bridal gown in bird poop, necessitating the last-minute purchase of a replacement.

The bride doesn’t care about the gown; in fact, she seems quite devil-may-care about the whole wedding, though she’s preoccupied with her role in it. “I’m the bride,” she tells a bellboy at the hotel before the wedding, “in case that’s the kind of thing that matters to him.” She tells her grandmother about the groom in a perfunctory way; he is tall and an elementary school principal. Her feelings about him are so simple as to be nonexistent.

Her brother Tom is another story. Their relationship was fraught before it fell apart; he’s brilliant, charismatic, and, of course, rather unreliable. Now that he’s out of her life, she doesn’t want to find him and doesn’t think he wants to be found. She does know how, however: He’s now a famous, though reclusive, playwright who made it big with a play based on her life called “Parakeet.”

To start, she seeks out a performance of the show, where several different actors play her at different ages. Watching the show, she’s struck by how tenderly he has preserved moments in her childhood ― the precise way she would line up her stuffed animals, lost forever when her mother trashed them in a fit of rage ― and infuriated by how he has butchered other memories.

“[E]very conciliatory sentiment fades,” she says, watching the scene in which a strange man attacks her at work. “Tom’s gotten it wrong again. When the man entered in real life, no one noticed. There is no memory in a play. A play is always present tense. I am newly injured in real time.”

It’s unclear which is worse: that he’s immortalized a false memory, or that he’s written a play that keeps her worst one continuously in the present, happening over and over again.

Though Tom has taken her story for his art, using it blithely to both wound and heal, she’s not alone in her agony. Her family rests on layers of trauma. Her grandmother, like the parakeet she inhabits, was a forced transplant to America, driven to emigrate from Basque country after conceiving a child with a Romany. Her mother is full of cold fury, her temper “a line of crystal in igneous rock.” Her brother, for all the charm and success, struggles with drugs and a deeper pain she can’t fathom. “My family: a complex system of dark islands seen from land,” she calls them.

Everywhere she looks for Tom ― the show, the afterparty, the after-afterparty ― he retreats, leaving her dangling. When the meeting finally occurs, the fabric of reality seems to slip again; Tom is not Tom, and she suddenly must reorient herself toward her most beloved, if estranged, living family member once again.

Meanwhile, amid her dreamlike quest to rebuild her family, her to-do list continues. She has final appointments with the wedding florist, which she repeatedly fails to show up for. She meets up with her best friend, a woman who is rapidly losing interest in her. She has a house call for her job, where she interviews patients of traumatic brain injuries for court testimony, attempting to piece together their scattered recollections and ongoing symptoms into a damning narrative. She has to buy a bird-poop-free wedding dress secondhand from a woman online; upon showing up to the woman’s apartment, she is rattled to find that the woman is an alternate-timeline version of herself, identical yet more carefree, and married to the very man who once broke her heart. She finds herself, during one scene, trapped in the body and mind of her mother, enduring the revelation that her cold parent is excessively flatulent and bursting with sexual fantasies.

The heartbreak and the humor of “Parakeet” both derive from this constant, unnerving sense of dislocation. The context feels off-kilter. The characters obsess over prepositions: “This is one of the nicest places I’ve ever stayed in Long Island,” she tells the bellboy. “‘On.’ He snaps to attention. ‘Long Island. We say on.’ ‘On Long Island?’ I test. ‘Does that make sense?’” Time moves at the wrong speed or happens all at once. She explains to a concierge that she looks grief-stricken because her grandmother died. “‘When?’ ‘Ten years ago.’”

The narrator tries to take refuge in the roles she holds, roles that anchor her by relating her to others: bride, sister, daughter. But mostly she is disappointed; she doesn’t know how to inhabit them. “How do you be a bride?” she asks her wedding hairdresser. “This is the first time I’ve been one.” (“Filled with words and energy,” is the hairdresser’s response. “Opinions.”)

The right words, the right roles, the right narrative: again and again, “Parakeet” tests ways of gluing oneself back together after being shattered. Sometimes the methods are laughable, absurd; others fail abjectly. Sometimes, as in the titular play, something works, if only for a moment.

Witty, raw and masterfully chaotic, Bertino’s novel works for more than a moment — it’s revelatory all the way through.

Calling all HuffPost superfans!

Sign up for membership to become a founding member and help shape HuffPost’s next chapter

[ad_2]

Source link