[ad_1]

Justin Timberlake‘s position in the Black community is a polarizing one. But with each passing year, the hatred half of that glass has increased with the benefit of social media-fueled cancel culture and revisionist history.

When his name came up recently as a possible opponent for Usher in a potential “Verzuz” battle, Interactive One Senior Culture Editor David Dennis Jr. was one of many who didn’t want to see the popular Instagram battle series gentrified.

JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE AIN’T INVITED TO THE VERSUZ

— David Dennis Jr. (@DavidDTSS) May 17, 2020

When Timberlake talked about being enamored with Air Jordans on an episode of ESPN’s docuseries The Last Dance, Brooklyn Hip-Hop Fest founder Wes Jackson echoed the sentiments of others who didn’t see the relevance of his input.

😂😂 News flash filmmaker: most people rescinded Timberlake’s cookout invite a while ago. He’s at Rosenberg’s with Action Bronson. We. Don’t. Care. https://t.co/sumndseqtB

— Wes Jackson (@westothejack) May 4, 2020

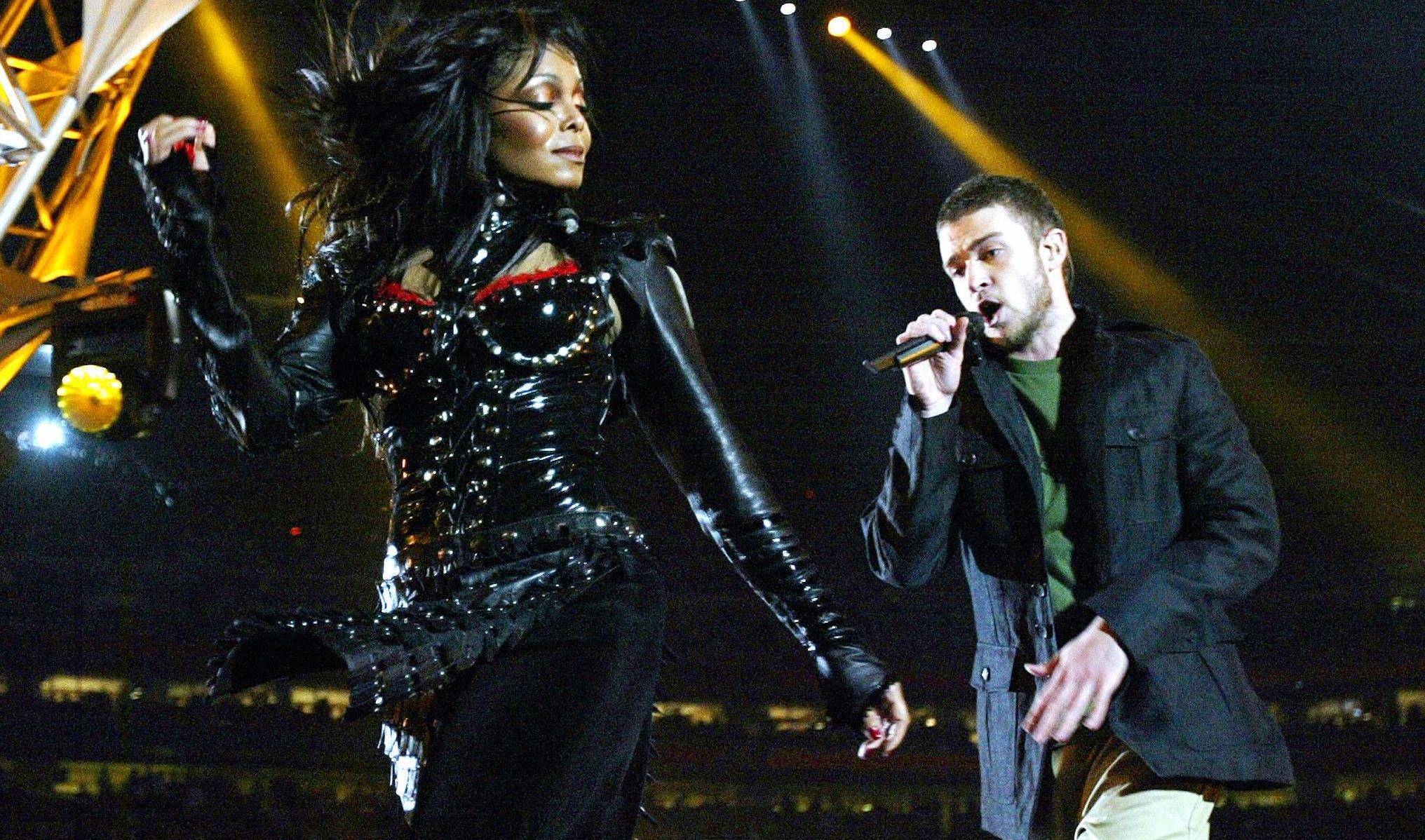

If you look at his actions — the Janet Jackson Super Bowl controversy, his pivot to country music — the singer checks off every box of being a culture vulture.

He’s a white artist who gains popularity and commerce by incorporating Blackness into his act. And he does this without fully entrenching himself into the hardships of Black Americans.

READ MORE: Amanda Seales slams Justin Timberlake for turning off comments on Ahmaud Arbery post

However, when you understand his music, his commentary about his music, and his actions, you’ll see that the man may not be maliciously profiting off of Blacks, per se.

It turns out he’s just like most white Americans fascinated with Black culture; he feels like he wants to participate in it based on how cool it makes him feel. But when the proverbial sh*t hits the fan, he hides his head in the sand like a dancing ostrich.

Justin Timberlake is not a culture vulture. Justin is just a coward. A dense coward at that.

On May 7, he posted a photo of Ahmaud Arbery to his Instagram page after a video of his murder went viral. “If you’re not outraged, you should be. Justice for #AhmaudArbery,” Timberlake wrote. He also turned off his comments on the post, to which comedian/actress Amanda Seales noticed, and was not pleased.

A week later, Seales called out Timberlake with her own IG post: “Dedicated to @justintimberlake and the white artists showing ‘solidarity’ posting about #ahmaudarbery but closing their comments/IG replies. Ain’t no half steppin. This is how you ally. You get in the weeds with your fans who are also fans of racist rhetoric.”

Singer Melanie Fiona summed it up perfectly when she replied to Seales’ post, “They ain’t built for the smoke sis. They just like to make s’mores round the campfire.”

You see, Justin had been down this road before.

During the 2016 BET Awards, actor Jesse Williams gave a notoriously impactful speech while receiving the Humanitarian of the Year Award. Williams’ speech included his views on police brutality and systemic cultural appropriation. Timberlake tweeted that he was “inspired” by the speech.

Black journalist Ernest Owens noticed Timberlake’s tweet, and was not impressed. He replied, ‘So does this mean you’re going to stop appropriating our music and culture? And apologize to Janet too.’

So does this mean you’re going to stop appropriating our music and culture? And apologize to Janet too. #BETAwards https://t.co/0FwBOQR24D

— Ernest Owens (@MrErnestOwens) June 27, 2016

Timberlake would reply to Owens: “Oh, you sweet soul. The more you realize that we are the same, the more we can have a conversation. Bye.” This exchange became national news, putting Timberlake in the dreaded ‘All Lives Matters’ club.

In a 2018 interview with Apple Music’s Zane Lowe, Timberlake disclosed that the inspiration behind his Chris Stapleton duet, “Say Something,” came from the online altercation with Owens.

He said when he and Stapleton were figuring out the subject matter of a song, Timberlake said, “I want to speak up and I want to say something, but I don’t want to get caught in the rhythm of something, because if the rhythm goes off, everything goes off the track.”

This turned into a lyric.

Lowe was able to connect the dots to the Twitter incident when he had Timberlake confirmed that the moment created a key phrase in the song: “Sometimes the greatest way to say something is to say nothing at all.”

Justin’s expression of regret in that instance is a large indicator that he is more afraid of getting dragged by Black Twitter than he is of getting in the trenches when it comes to Black injustice.

It also revealed “Say Something” as an anthem of cowardice and non-commitment.

Justin may not think that he’s a culture vulture, despite all the signs pointing to the contrary. The evidence shows, though, that he is too shallow to be a conscious vulture.

After analyzing his music and his influences, you discover that everything for him is surface level. He sees what he likes and reacts based on that. It’s no different than the current ‘react first’ culture, where many base their definitive decisions on music after only a single listen.

Justin has cited numerous Black singers as key influences on him. In a Rolling Stone cover story, he named dropped Al Green, Stevie Wonder and Marvin Gaye as musicians who inspired him as a child in Memphis, TN. He also said during a 2002 BET profile that Donny Hathaway was his favorite singer.

Based on Timberlake’s singing style and lyricism, you see he is only inspired by the timbre of Hathaway’s voice, not the feelings and emotions driving his vocal performances.

If he looked just a hair underneath the surface, he would see the blues, youthful exuberance and desperation in Hathaway’s work. You know that he didn’t look because there’s but a hint of blues or desperation in Timberlake’s music.

The closest he’s ever gotten came when he was still with N*Sync, when he co-wrote and recorded “Gone.” However, Timberlake would later reveal that “Gone” was originally composed for Michael Jackson. Therefore, Justin presumably mimicked Jackson’s idiosyncratic singing style.

In his “I’m Ready” promo for 2013’s 20/20 Experience, Timberlake conceded that he can only make music when he has something to say. “I don’t know if I could physically torture myself year in and year out and expect it to fulfill me the way that it does and the way that it is right now,” he said. So, seven years between albums, and what he had to say was, “I be on my suit and tie shit,” and “you got me hopped up on that pusher love.”

The real problem with Timberlake is he actually believes his music is deeper than it is. In the Man of the Woods EPK, he described the sound as “modern Americana and 808’s.” He made it seem like he was summoning his Memphis roots and tried to marry them with his family life and previous dance sounds.

After listening to this album, it’s evident that he tried to have his cake and eat it too. Timberlake wanted to expand his audience without sacrificing his core sound. It didn’t work. It was panned universally, but with the Black community, it was another example of a white artist using Black sounds to get to the top and writing it off once you’ve crested the peak.

Despite attempting to exhibit solidarity with Black plight, he’s yet to address it artistically. The only time he’s ever made any kind of socio-political statement on his albums is on 2006’s “Losing My Way” where he tells an unconvincing, first-person account of a man fighting drug addiction.

In fact, the only emotion Justin has been able to organically convey on wax is bitterness. Songs like “Cry Me a River” and “Last Night” and “What Goes Around…” find Timberlake evoking the scorn of his 2001 break-up with ex-girlfriend, singer Britney Spears.

Timberlake’s denseness was evident when he released “Take Back the Night” in July 2013. He received push back from the Take Back The Night Foundation, an organization well known for taking stances against date rape and domestic violence against women.

Timberlake released a statement to Radar Magazine to address the situation, claiming he had no prior knowledge of the organization. “It is my hope that this coincidence will bring more awareness to this cause,” he said at the time. The fact that he felt this misunderstanding would bring light to a non-for-profit that was founded in 1976 and has international support speaks to how clueless and egocentric he is.

Justin Timberlake has done himself no favors in regard to the loathsome feelings he attracts from Black commentators and consumers. However, his co-conspirators must be taken into consideration for their contribution to his so-called appropriation.

Producers Timbaland, The Neptunes, and songwriter James Fauntleroy all contribute and benefit from the success of the music, which only justifies the polarizing stature of Timberlake, who is the face of it.

Surely, he wouldn’t be famous without juxtaposing himself to these Black stars, so shouldn’t they get some blame too? Should the Black community condemn Timbaland, Pharrell, Fauntleroy and other collaborators like T.I., Meek Mill and SZA?

More so, since Timberlake is the weak link in the studio process (see lyrics to “Nothing Else,” “Supplies,” and “Spaceship Coupe” as examples), do they actually deserve most of the blame for elevating someone who uses the culture but isn’t of the culture?

The irony of all this is Timberlake doesn’t need the Black audience. Out of the 24 singles Timberlake’s released as a lead artist, only five of them charted on the Billboard R&B charts.

But he clearly wants to be in the good graces of Black Americans. He can start by going out on a limb for them, socially as well as artistically.

But after so many examples of spinelessness and delusions of grandeur, he may have to accept that he may never be considered the ally he thinks he is.

Matthew Allen is a Brooklyn-based TV producer, director and award-winning music journalist. He’s interviewed the likes of Quincy Jones, Jill Scott, Smokey Robinson and more for publications such as Ebony, Jet, The Root, Village Voice, Wax Poetics, Revive Music and Soulhead. His video work can be seen on PBS/All Arts, Brooklyn Free Speech TV and .BRIC TV.

Matthew Allen is a Brooklyn-based TV producer, director and award-winning music journalist. He’s interviewed the likes of Quincy Jones, Jill Scott, Smokey Robinson and more for publications such as Ebony, Jet, The Root, Village Voice, Wax Poetics, Revive Music and Soulhead. His video work can be seen on PBS/All Arts, Brooklyn Free Speech TV and .BRIC TV.

Have you subscribed to theGrio’s new podcast “Dear Culture”? Download our newest episodes now!

[ad_2]

Source link