[ad_1]

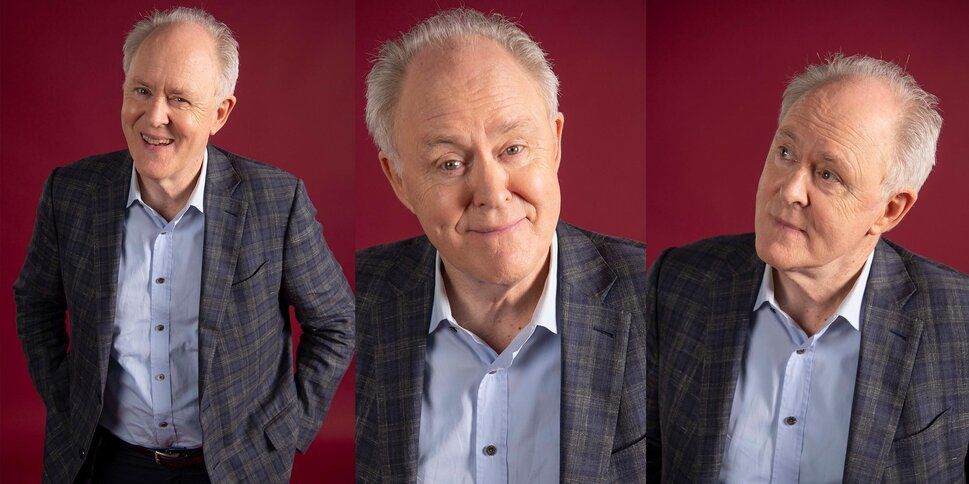

If I don’t interrupt Blythe Danner and John Lithgow soon, they might never shut up.

Danner and Lithgow are sitting in a conference room at HuffPost’s New York office, signing posters for their new movie and chatting back and forth as I ask which friends they have in common. Later, their rapid-fire crosstalk will be impossible to transcribe. Mentions of Meryl Streep, Rosemary Harris, Christopher Walken, Mandy Patinkin, Sam Waterston and Mary Beth Hurt ensue.

“I always thought, ‘With a name like that, she’s not going to go anywhere,’” Lithgow says of Streep. He recalls his and Danner’s patter on the film’s set: “This is the way we talked the entire time. We wore everybody out. All the makeup people, they thought we were two cranky old fools.”

After the veteran actors are done scribbling a few dozen signatures apiece, they settle in and offer professional-grade attention. Danner seems unsure where she is at the moment ― “And you are with …?” she asks, and I remind her this is a HuffPost interview ― but I guess that’s the way it goes when you’re being herded around the city by publicists for a day full of press.

“The Tomorrow Man,” which opened in select theaters Wednesday, is a romantic dramedy starring Lithgow as a divorced doomsday prepper who spends most of his time stocking a fallout shelter and posting comments online about apocalyptic conspiracy theories. In a supermarket parking lot, he meets a widow with her own set of neuroses, played by Danner. From there, they embark on a slow and steady courtship.

Danner, 76, and Lithgow, 73, don’t recall the first time they met. It was probably sometime in the early 1970s, when they were both rising stars in the New York theater sphere. Across countless plays, films and TV series, Danner’s and Lithgow’s careers have only accelerated. In the ’90s, they indoctrinated their children in the business. Yes, that means Gwyneth Paltrow, but also her brother, Jake, who has directed episodes of “NYPD Blue” and “Boardwalk Empire.” Lithgow’s son Ian starred alongside his father in the popular sitcom “3rd Rock from the Sun.”

As our half-hour conversation progresses, Danner and Lithgow talk about their careers and the state of the industry, including controversial former collaborators like Bob Fosse and Woody Allen, as well as Streep, Goop, Broadway and that time Danner’s au pair almost burned down her house. But first, because it’s only fitting, we discuss the end times.

Does either of you have a doomsday plan?

Danner: You mean do ourselves in?

Lithgow: No. I’m like most of the human race: My powers of denial are well-developed ― you know, just don’t think about the end of things. You can’t live in this day and age without having dire and dystopian thoughts now and then. But I just sort of live in the moment.

Danner: I think John is the healthiest actor I’ve ever known — the least neurotic, the least egotistical, hung-up.

Lithgow: You see, she didn’t really get to know me.

Danner: Truly, and I think that’s how he lives his life. For instance, I came to see him in his play and he said, “Why didn’t you tell me you were coming?” and I said, “Well, I never want to know who’s coming.” Because I’m so neurotic and I’ll be thinking the entire time, “Did they like that?” or “What does he think about this move?”

Lithgow: No, I do that too. And she’s plenty healthy, too. We just absolutely hit the ground running as if we had worked together a hundred times. The fact is, both of us have done a hundred theater jobs, and it felt like we were doing a play quite often. The way the movie is written, it takes its time. It’s very much about the characters. It’s very literary. [Director Noble Jones] gives both of us speeches, and she always knew her lines.

Danner: He actually was kind enough to test me in the car going home one night. Then, I got everything very wrong. And I just detected a slight note of, “Get it right, Danner.” I was projecting. I was thinking that of myself. It was wonderful to look into his eyes, and that safety net was there.

Lithgow: And that’s exactly how I felt.

At this point in your careers, having done so much theater and film and television, can you read a script and understand why you’re the one who was thought of for that role?

Danner: I think I’ve always had a bit of a quality of being unsure that sometimes translates in my work, being a bit scattered, being not always grounded, and I think maybe [Jones] thought of me in terms of that. I love what John says: “They’re like two wounded birds.”

Lithgow: I think he loved the partnership of the two of us, and there aren’t a lot of us around anymore, you know what I mean? Let’s be honest.

Danner: Of a certain age.

Lithgow: For us, the roles are so fascinating because the roles deal with issues of fear and fear of losing your viability and your own approaching mortality and fighting against that and defying. It’s great.

Blythe, you had your first lead role in a movie only a few years ago, at 75, in “I’ll See You in My Dreams.” And now here’s another. What do you make of your newfound movie stardom?

Danner: I don’t think I’m a movie star. I’ve always been a company person who loves being in a company. I actually turned down “I’ll See You In My Dreams” [at first]. I said, “Oh, I can’t carry a movie. I wouldn’t have the stamina. I couldn’t possibly do it.” And when I did, I was thrilled and so surprised and delighted. I never really loved film because it was so intrusive, and I couldn’t get comfortable in front of the camera. [To Lithgow:] You made the transition very easily when you did “The World According to Garp.”

Lithgow: Yeah, I was uneasy in film because mainly filmmakers would be constantly telling me to take it down ― you know, to pull back — because a stage actor’s impulse is to act for the last row of the house. My big breakthrough came when I did the “Twilight Zone” movie, with George Miller directing it. This is George Miller of “Mad Max,” so everything had to be huge. Nothing was ever enough for George. “More! More! I want to see your face crack.” OK, George, have you ever got the right actor. And that was incredibly liberating. I make a deal with directors. I tell every one of them upfront, “I’m going to be very excessive right upfront. Don’t worry, just simply tell me to take it down.” But if you don’t have that, you’ll never have it in the editing room either, even when you wish you did. I’ll give a big performance and then it’s up to you to modulate it. And it’s in the nature of moviemaking that you shoot every single angle six times, so give them six versions.

Have you ever gotten a particularly interesting note about how to modulate or take something down?

Lithgow: I loved the experience of working with a director named Ira Sachs in the movie “Love Is Strange,” with me and Alfred Molina.

Danner: I saw it. it was wonderful.

Lithgow: A lovely, gentle movie, and Ira’s constant note to both Alfred and me — because both of us are old hambones — was, “No acting on this one. No acting, no acting.” We heard it over and over, and at first it really pissed us off and then we gave ourselves over and we knew exactly what he was talking about. And you see that movie, and it’s the most unperformed film. It’s almost like the audience is seeing these people by accident.

Danner: Very deeply felt.

Lithgow: George Miller and Ira Sachs are the two ends of an enormous spectrum, and you have to go on whatever journey the director is taking you on. That’s in the nature of the beast. Put yourself at his disposal or her disposal, and then do what they want and hope that they don’t take it all away in the cutting room, which they do.

Danner: That’s the thing. That’s what I prefer about the theater: You really do have so much more control.

Lithgow: And the extreme of it is being cut entirely out, and that’s happened to me before too. You didn’t know I was in “L.A. Story.”

Only because it’s on your IMDb page. Blythe, is it true that you were up for a couple of roles that made Meryl Streep famous, specifically “Kramer vs. Kramer” and “The French Lieutenant’s Woman”? You would have become a movie star much faster with those.

Danner: I wasn’t offered them. I was offered a wonderful one. I won’t say what it was, but it was with Paul Newman and [the producer of a play Danner was doing] wouldn’t let me out for one day in Europe. My husband [film director Bruce Paltrow] was so angry. He said, “From now, on I’ll let everybody out.” When he died, Washington ― what’s his name?

Danner: Denzel thanked Bruce. He said, “I’ll never do that to an actor. You should allow somebody to have another good role.” There was another one ― but I never say which ones they are because I don’t think it’s good manners ― that I actually was offered and couldn’t do because my au pair girl at the time had burned the television with an iron. She was ironing, and she put it on the television. I said, “I can’t leave these children!” That was a nice juicy one, but you know.

But the “Kramer vs. Kramer” rumor seems familiar to you.

Danner: Well, only that I met with the director. I think I met Dustin [Hoffman] for it, and good God, why wouldn’t they take Meryl [Streep] over me or anybody else? I was up for them.

John, one of your first movies was “All That Jazz,” directed by Bob Fosse, who’s the subject of a TV show right now, “Fosse/Verdon.” That show spends some time reckoning with Fosse’s reputation as a womanizer, and we’re at a moment when many Hollywood elders are being reexamined. What do you make of seeing your old friends and collaborators reassessed in the public eye?

Lithgow: Well, I worked only briefly with Fosse, but I was thrilled to have the experience. He was the most intensive, work-oriented director I have ever worked with. He had such blinders on, which I think is very much like a choreographer who becomes a director. I remember drumming my fingers on one take and him wanting that on every single take ― it was those Fosse fingers. I did two scenes, each of which was a day of shooting, and then he put me into the audience for the big final sequence along with all the other minor players that he filmed. And so I sat and watched him work for nine days with Ann Reinking and Ben Vereen and Kathryn Doby and all these greats. It was such an education. I just loved the experience, and I feel really proud that I got to work with Fosse. I never saw all the grittier aspects of him, but he put it right up there on the screen. “All About Jazz” was all about it. He just can’t keep his hands off beautiful women, and he was obsessed with death. He would keep pressing on even though he had a heart that didn’t work anymore. And he kept smoking, and he made Roy Scheider smoke like a chimney. He wasn’t coy about it.

Danner: Is this show [“Fosse/Verdon”] still on?

The season is on right now, yes.

Danner: I don’t know how to stream, but I guess I could go back. The little that I know of Gwen Verdon, having met her once or twice, [Michelle Williams] seemed to have captured that there.

You came up in the theater scene around the ’60s and ’70s. Did you meet Fosse?

Danner: I met him. He never came on to me. I guess I wasn’t attractive enough. But I did go in and meet him. I don’t know what it was for.

Lithgow: I actually auditioned for “Chicago.”

The original Broadway production?

Lithgow: Yeah. That was my first experience with Bob, and he had me come back. It was to play Billy [Flynn, the lawyer first portrayed by Jerry Orbach]. And I also met him when “All That Jazz” was going to be a straight movie. He was very interested in me as an actor. He just thought I was interesting, and then … the great New York film director Sidney Lumet was playing my part because he had all these real people playing real people, Jules Fisher playing Jules Fisher, and Lumet was playing this director. Then, things went late and Sydney couldn’t do it ― he had to get on to his movie, so [Fosse] had to find somebody immediately, and he called me the night before.

This is a bit heavier, but Blythe, you starred in a few Woody Allen movies early in your screen career. His legacy is also being reexamined. How does that make you feel?

Danner: I don’t mean to be neither here nor there, but part of me says I don’t believe that he should be completely wiped off the face of the earth. I started getting very suspicious ― not suspicious, but down on the whole thing when Kirsten Gillibrand got rid of Al Franken. I was so pissed off.

Lithgow: It was very upsetting.

Danner: I hate to be wishy-washy about it, but I just don’t think you can go down the line and say, “This person … ”

Lithgow: We’re just in insane times. If any of us was judged by the worst moment of our lives, none of us would work again.

Hollywood, Broadway and the whole industry at large have changed a lot since you both entered it. How different does it look from where you’re sitting? Is it better?

Lithgow: Broadway is hugely successful. When we worked on Broadway, half the theaters were dark and had been dark for an entire year. You knew because they still had the marquees of shows that had closed a year before. And there were hookers lining Eighth Avenue, sex shops everywhere. Forty-second Street used to be somewhere you never went near. It was an enormously different place. Of course, it’s now a gigantic engine of the New York economy and the tourist industry, and it employs lots and lots more people, so things are better, of course. But you can’t help missing the things that were on Broadway. They were fantastic. When I had my Broadway debut, “A Little Night Music” was across the street, “Pippin” was down the street, “That Championship Season” was down the street. A few years later, along came “A Chorus Line.”

Danner: And they were the originals. Now, all you have is revivals.

Both of you have enjoyed a particularly active decade of moviemaking, even as franchises swallow part of the business. With the exception of John doing “Rise of the Planet of the Apes” and “Daddy’s Home 2,” you haven’t gotten embroiled in any of those huge enterprises.

Danner: I’ve never been offered them.

Lithgow: It’s easy to stay uncorrupted when you’ve never been asked.

Danner: I said to my daughter I loved it when she saved the world. Otherwise, I only see them if she’s in them.

That’s a big aspect of how Hollywood had changed. “Terms of Endearment” made huge money when it came out, but we couldn’t expect that for it today.

Lithgow: Yeah. The only movie role of that kind I’ve played is “Buckaroo Banzai,” which of course was a whole sendup of the whole franchise superhero movie, long before they became the dominant genre of the profession.

Blythe, what Goop products do you own?

Danner: Well, almost everything. No, that’s not true. The face stuff. I love the scrubs. I don’t know how she lies in bed at night and dreams these things up. I love them.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

REAL LIFE. REAL NEWS. REAL VOICES.

Help us tell more of the stories that matter from voices that too often remain unheard.

[ad_2]

Source link