[ad_1]

If scientists ever find evidence of extraterrestrial life, will they be able to know whether it’s been there all along, or if it evolved from the various microbes that humans have brought, and shot, into space? This question fascinates Jenna Sutela—a Berlin-based Finnish artist who probes the interconnections among humans, microbes, and machines, focusing on interspecies communication and symbiosis. Such notions also fascinate science historian Sophia Roosth, who exchanged ideas with Sutela via Zoom in June. Roosth specializes in the history of the life sciences, and her 2017 book, Synthetic: How Life Got Made, explores how life has been defined, designed, and artificially created by late twentieth-century genetic engineers. Below, the two discuss methods they’ve developed for the tricky problem of speaking about (and sometimes for) microbes and minerals.

SOPHIA ROOSTH How has the pandemic affected your thinking about biological interconnectivity?

JENNA SUTELA We’re all experiencing this invisible force that’s creating all these intricate choreographies around itself. We’re painfully aware of this other life-form—the virus—that we live with. The pandemic is challenging our position as the planet’s dominant species.

I had another recent experience that prompted me to reflect on how it feels to be human: like you, I was recently pregnant.

ROOSTH My pregnancy definitely influenced my thinking about biology . . .

SUTELA Mine, too. [Art historian] Caroline A. Jones recently reminded me that, eons ago, a retrovirus introduced a gene that allows the placenta to fuse with the uterus. It also altered the immune system so that the body would accept another being and not attack the fetus, [enabling mammals to evolve from egg-laying species].

ROOSTH Early in my pregnancy, I gave a lecture in Montreal: I was asked to talk about what an organism is. So I went back to a common nineteenth-century definition . . . and I realized that, as a pregnant person, I did not qualify! I no longer had an isolable body, nor an exterior that was my own. I was no longer genetically separate from any other living thing. I wasn’t metabolically self-sufficient.

I have to say, this didn’t surprise me, but I was astonished anew by how different these kinds of theories would be, had they been written by women. How does this definition impact the way we understand self versus other? Or, as your work asks, the distinction between organism and ecosystem? All of these definitions are artifactual and historically specific.

SUTELA Definitely. Ursula K. Le Guin put it well in her essay, “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction” [1986], where she says that the first human-made tool was not a weapon but a pouch. In my work, I’m thinking of the human body as this carrier bag for bacteria, babies, germs, and parasites.

Carl Sagan said, more broadly, that we are transitional creatures between the primeval mud and the stars.

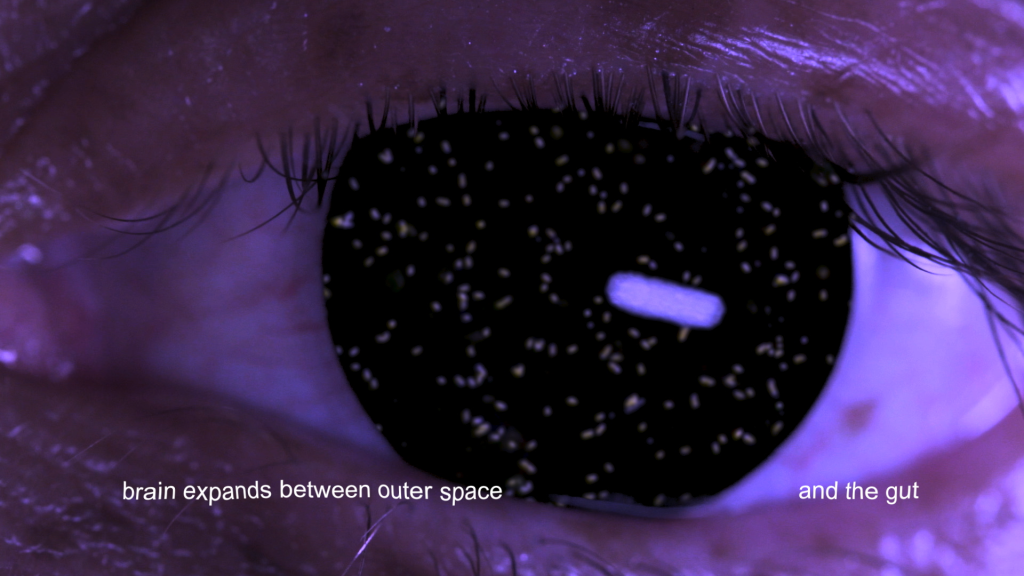

ROOSTH Your video Holobiont [2018] is about this relationship between the interplanetary and the bodily interior. You suggest sending the bacterium Bacillus subtilis, which lives in our gastrointestinal tracts, to Mars.

SUTELA Yes, a holobiont, as defined by [geo-biologist] Lynn Margulis, is a unit made up of one species, plus the other species that live in, on, or around it. Bacillus subtilis has been sent in spacecraft in order to test the possibility of life in outer space, and it seems to be doing pretty well.

Jenna Sutela: Holobiont, 2018, HD video and sound, 10 minutes, 27 seconds.

SUETELA You’re in the process of writing a series of “mineral autobiographies.”

ROOSTH Yes, I’ve been experimenting with the question: what happens when you tell a story from the perspective of a fossil or of a rock?

Mark A. Wilson/Wikipedia.

I’m still working on the series. . . . I sent you one that I wrote about ooids, a type of soft sand, usually found in shallow, tropical saltwater. Each grain contains this entire microbial world inside. The ooid has been a subject of intense geological and biological debate, because it defies ordinary definitions of life. It’s between a rock and a living ecosystem. . .It’s a holobiont.

SUTELA In that text, you write about life and nonlife: not as two distinct categories, but rather, as “time-bound oscillations.” You mention, for example, that seeds sometimes turn to stone if you wait long enough. I wanted to ask you about the idea of co-opting strangers and having them co-opt us, which you discuss in that text.

ROOSTH That’s a reference to Margulis’s work, which I borrowed from in order to question what, exactly, an organism is. I wanted to expose the insufficiency of the standard definition. I also wanted to bring in the element of time: not just the duration of a life span but also the longer duration of geological time. How does that shift the way we think about life as a time-bound entity?

I find it interesting that, in trying to understand what a holobiont is, we both ended up using the first person.

SUTELA I wanted to try and let the microbes speak through me. I like to consider my practice a collaboration with other life-forms. I realize, though, that while I can decide to work with microbes, I’m not sure if they can really decide to work with me. It’s tricky, being a human and imposing our language upon them.

ROOSTH That is something I’ve been grappling with, too. . . As an anthropologist and a historian, I’m not trained in creative writing, but I’ve been pushing myself to play with form. I’ve been looking at a few texts I admire as models, like Jules Renard’s Nature Stories [1896], a collection of tales told from the perspective of different animals, with entries ordered according to the Scale of Nature [a hierarchical taxonomy of species]. Italo Calvino [1923–1985] also uses the first person for entities that wouldn’t normally be able to speak for themselves in ways that humans can easily understand.

SUTELA You also addressed this challenge in your essay “Screaming Yeast.” I noticed that, at one point in your ooid autobiography, you switched from “I” to “we.” That maneuver reflects how, as a holobiont, it’s both one unit and many organisms.

Wikipedia

Another tool I use to try and get some distance from anthropocentric language is machine learning. Working with artist-programmers Memo Akten and Damien Henry for my video nimiia cétiï [2018], I tried to give some sort of voice to Bacillus subtilis. I trained machine-learning algorithms on two sources: first, footage of the bacteria’s movements; second, sound that I recorded based on Hélène Smith’s Martian language from the nineteenth century. Smith was a French medium who channeled Martian messages. The messages were documented only in writing, so I couldn’t know exactly what they sounded like . . . but I figured the language must have had a French accent, so I just went for it! The language that the algorithm created sounds almost like a chorus, and features a weird humming sound. . . . It’s eerie. It’s as if the bacteria and the machine collaborated, and then I, a human, edited it all together.

Photo Mikko Gaestel.

I have a computational background: the slime mold was my gateway to microbes. Slime molds are single-celled yet “many-headed” organisms that can congregate to form a larger, unified body. They’re regarded as a kind of natural computer: some companies are trying to develop hardware using slime molds as a material. For a performance, Many-Headed Reading [2016], I ate a slime mold species called the Physarum polycephalum, thinking of it as a form of AI, allowing its hive-like behavior to “program” me. I wanted to highlight how we’re interwoven with microbes and machines alike. Though we may have created machines, they’re also taking on a life of their own.

ROOSTH In both Holobiont and nimiia cétiï, you allude to panspermia, which is something I’ve also written about. Panspermia literally means “all seeds,” or “seeds everywhere,” and is the theory that life arrived on Earth from other planets.

SUTELA Yes, I’m quite curious about the idea of life existing throughout the universe, and possibly being distributed by meteoroids, asteroids, planetoids, comets, and spacecraft.

ROOSTH Did you hear about the Beresheet landing? Last year, an Israeli company launched a rocket that crashed into the moon, and spilled tardigrades there—tardigrades are microorganisms from Earth. They’re often considered evidence of alien life, because they are capable of living in pretty much any environment on Earth. They can withstand extreme cold, extreme heat, radiation, vacuums. But I find it ironic that their success at being earthlings is interpreted as evidence that extraterrestrial life is possible.

In 2007 the European Space Agency shot tardigrades into orbit. They survived and were able to reproduce in space! This experiment was part of the agency’s effort to protect Earth against microbial invasion from other planets. This effort has a long history. There were early NASA conferences, even before the Apollo programs, where scientists were asking: what would happen if we put microbes on the moon? If we find life on other planets, how will we know that it’s alien, and not just us? Again, it’s a question of self versus other.

Schokraie E, Warnken U, Hotz-Wagenblatt, A.; Grohme, M.A.; Hengherr, S; et al./ Wikipedia

There’s a good chance the tardigrades on the moon will reproduce. . . .

SUTELA Wow. Even though most of the space agencies around the globe have committed to the planetary protection agenda, and have told one another to go and clean up any mess they left in space, that’s obviously very difficult to do. For Holobiont, I was inspired by Jain monks and their efforts to let other life-forms flourish in peace, which likely means getting rid of humans.

ROOSTH These days, we’re all very attentive to how difficult it is to ensure that any surface is totally antiseptic! Try as we might, we’re all infecting others, all the time, everywhere. I can’t help but wonder . . . did anyone disinfect Elon Musk’s car when they shot it into space? A bunch of white men have shot their genetic material into space in a sort of reverse panspermia . . . Musk, geneticist George Church, biotechnologist Craig Venter, businessman Nova Spivack . . .

SUTELA Maybe panspermia needs a new name . . . panovium! I visited the Planetary Protection section of the European Space Agency. . . . They disinfect things like the probes that go under the surface of Mars. But some of the people who work there acknowledge that when the spaceship leaves Earth, even though it’s sealed, microbes can probably get in anyway. If there’s anything we’ve learned during the past few months, it’s that we can’t completely control life. We’re all interconnected. The “alien” is in us.

—Moderated by Emily Watlington

[ad_2]

Source link