[ad_1]

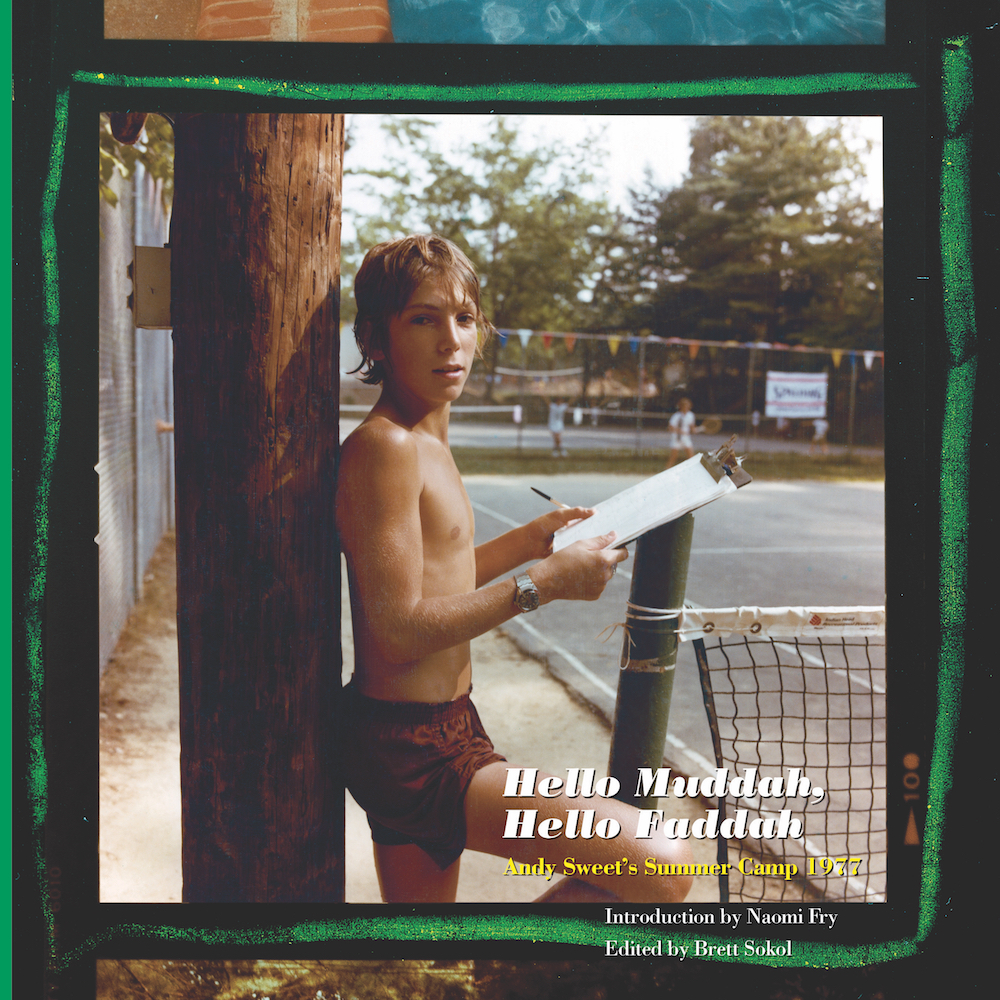

In the great adolescent divide between camp people and non-camp people, the late photographer Andy Sweet was ardently pro-camp. In 1968, at age fourteen, he began attending Camp Mountain Lake, a sleepaway camp in North Carolina that catered primarily to Jewish families from his native Miami, and then returned as a counselor and photography instructor. During the summer of 1977, while an MFA student at the University of Colorado at Boulder, he took a series of pictures at Camp Mountain Lake that would become the basis of his thesis project. Though the negatives were lost after Sweet’s untimely death, in 1982, the series has been meticulously reconstructed from surviving contact sheets and reprinted in Hello Muddah, Hello Faddah: Andy Sweet’s Summer Camp 1977, a new volume from Letter16 Press, edited by Brett Sokol with an introduction by Naomi Fry.

Together with Shtetl in the Sun: Andy Sweet’s South Beach 1977–1980, published by Letter16 last year, the book offers a compelling portrait of an artist who possessed a preternatural sense of self despite his young age, and who was well on his way to cultivating a trademark style. Inspired by artists like William Eggleston, he shot exclusively in color at a time when black-and-white was still synonymous with fine art. He also viewed photography as a resolutely subjective enterprise. Part of a new generation of artists redefining documentary around sentiment and personal experience, Sweet believed that photography was not the proper place for impartiality, for the process required “belonging, knowing, and understanding.” It was intimacy, not detachment, that permitted the artist to properly bear witness, and as Fry observes, Sweet’s photographic gaze was “always tempered by a decidedly non-scientific sweetness, humor, and sadness.”

Sweet photographed what he knew and what he loved, saturating these realities with the lushness of full color. In the series collected in Shtetl in the Sun, he paid homage to the Jewish retirees transplanted to Miami’s South Beach from Eastern Europe, by way of the Mid-Atlantic—a peculiar half-assimilated tribe (surrogate grandparents, all) who wedded the traditions of the Old Country to the vices and pleasures of the new. A precursor to this body of work, the photographs in Hello Muddah, Hello Faddah are best understood as its complement, reckoning with the younger Jewish-American set to which Sweet belonged. Born in the United States, the boys and girls of Camp Mountain Lake were secular and assimilated. But despite being more American than Jewish, they still straddled the hyphenate of their identity, participating in the star-spangled summertime idyll of camp within a closed and insulated circle, one that was implicitly Jewish, if not explicitly so.

That Sweet was a member of this circle is clear from the photographs, for he had an obvious gift for putting his campers and fellow counselors at ease. In shot after shot, they register the camera as one might acknowledge the presence of a friend. The youngest campers, still uninitiated in self-consciousness, deliver grins so earnest they border on grating. The big kids, perhaps emboldened by the lack of parents, use the lens as a mirror for rehearsing new attitudes without repercussion. In one of my favorite pictures, three older girls sit in a row, crossing their legs in identical twists, each practicing a slightly different version of coquettish aloofness: one pouting, one stone-faced, one armed with a prop cigarette. Its masculine corollary might be found some pages earlier, in a shot of a shirtless, tube-socked lothario-in-training. Posing mid-workout, he flexes while holding a barbell and curls his upper lip as if to emphasize the moustache fuzz that has accumulated there, just north of his orthodontia.

The adolescence preserved here is Jewish and pure 1970s. (If the tube socks and indoor smoking are not period giveaways, a camper wearing a shirt that says i love the fonz surely is.) Its charm, however, is far more universal. In Sweet’s pools, canteens, and baseball fields, you can almost feel the cling of a swimsuit on wet skin, almost taste the ketchup on a hot dog, almost smell the scent of fresh-cut grass. Sweet has left behind a gorgeous record of American summertime, or at least our collective fantasy of it. It is made all the more tantalizing by the circumstances of the book’s release, at a time when these seasonal rituals have been put on hold.

[ad_2]

Source link