[ad_1]

“It’s A Wonderful Life” was supposed to mark Frank Capra’s triumphant return to Hollywood. After four years making war films with the Army, he was running his own movie studio on his own terms and had crafted an intensely personal statement with his latest film ― an expression of everything the Sicilian immigrant loved about his adopted country. He called it “my kind of film for my kind of people.”

But the people, it seemed, had spurned him. “It’s A Wonderful Life” lost roughly $500,000 at the box office, a staggering sum for a director who began his tenure at Columbia Pictures on films budgeted at $18,000 a flick. The critics were unimpressed. The New York Times called it “too sticky,” a “figment of simple Pollyanna platitudes.” The New Yorker ruled Capra’s sentimental dialogue “so mincing as to border on baby talk,” while The New Republic denounced the film as a failed effort “to convince movie audiences that American life is exactly like the Saturday Evening Post covers of Norman Rockwell.”

Capra’s career never recovered. By the time he published his memoir in 1971, Capra hadn’t been behind the camera in a decade, and the negatives for “It’s A Wonderful Life,” which he came to call “the greatest film I ever made,” were decaying on studio shelves.

But in a historical accident too improbable for the silver screen, America was about to prove Capra right. Beginning in the mid-1970s, “It’s a Wonderful Life” was transformed from an obscure relic of Old Hollywood into an essential cultural monument representing the two things Capra loved most: America ― and, to Capra’s surprise, Christmas.

Its resurrection would be almost as strange as its creation. “It’s a Wonderful Life” is a wonderful mess ― an alchemic triumph of hucksterism, misplaced nostalgia and stylized high-concept visual metaphor that somehow coalesced into one of the greatest works of American art.

Beginning in the mid-1970s, ‘It’s a Wonderful Life’ was transformed from an obscure relic of Old Hollywood into an essential cultural monument.

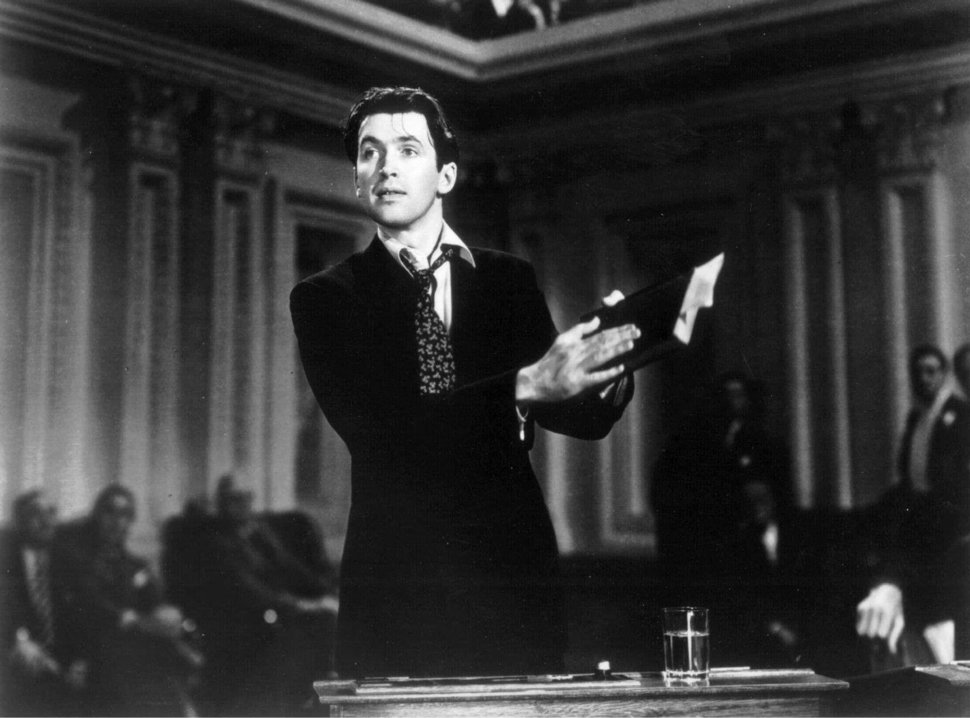

“It’s A Wonderful Life” is the story of a man whose big-city dreams are persistently thwarted by small-town realities. Capra’s grandest ambitions and deepest anxieties are channeled by Jimmy Stewart, who plays George Bailey, a bank manager both doomed and saved by his community. This was a remarkable artistic achievement. Capra’s world had never resembled the comfortable enclave of Bedford Falls that he conjured on film.

Capra came to the United States in 1903 at the age of six, the youngest of seven siblings. He liked to describe his life as one long Horatio Alger romp from “the riff-raff of Dagos, Shines, Cholos, and Japs” to fame and fortune as the most popular director in Hollywood. “Sure I was born a peasant,” he wrote in his memoir, “but I’d be damned if I was going to die one.”

The truth was more interesting. Capra worked plenty of tough-it-out daily grind jobs as a young man, but according to a 1938 Saturday Evening Post profile, he also spent a good chunk of his 20s as “a migratory small-time racketeer,” “tin-horn gambler” and “petty financial pirate.” He sold stock in fake mining companies to unwitting farmers, assisted by a 60-pound glittering rock he used as a sales prop. He rode up and down California in railroad boxcars hunting new marks, contracting gonorrhea at least twice during his travails, according to his biographer Joseph McBride.

These years as a small-time hustler brought Capra to dozens of small towns, where he developed a sense of affection for the people he took advantage of. “I found out a lot about Americans … I met a lot of Gary Coopers,” he told McBride. “I loved them.”

He would eventually put this education to work as a director. His best films are infused with a deep reverence for what film critics began to call “the common man.” But Capra also looked down on the people he used as protagonists. He knew first-hand how easy they were to manipulate. As an immigrant, Capra battled all his life to be accepted as an American ― but he had no desire to be an ordinary American. He didn’t want to join the middle class. He wanted to leapfrog it.

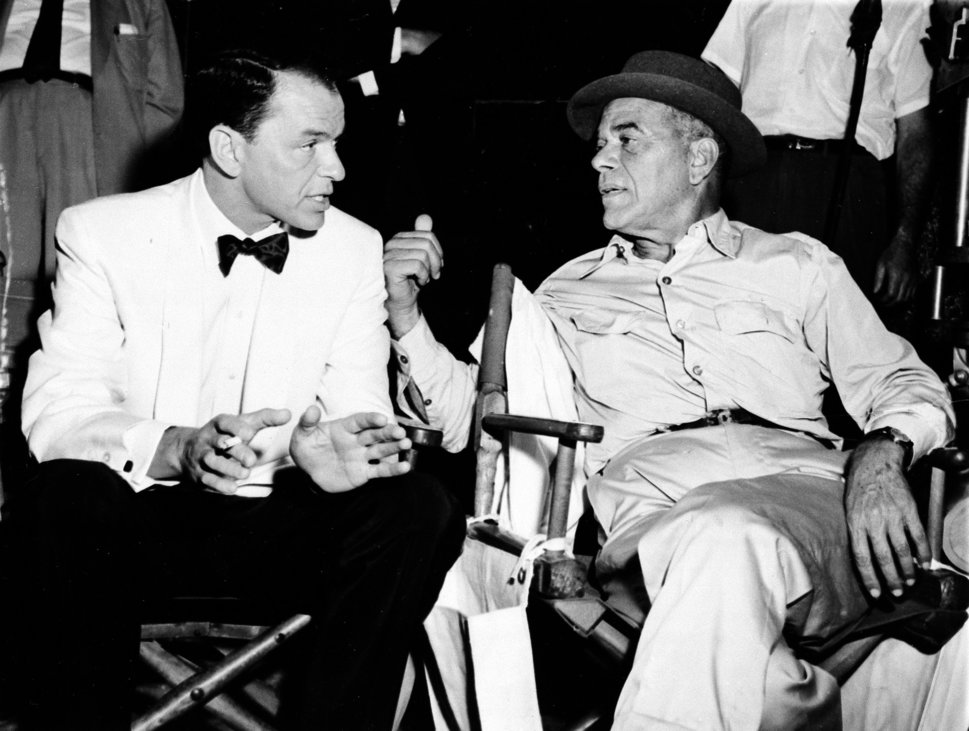

AP

The tension between Capra’s devotion to and disdain for working people is the emotional engine for “It’s A Wonderful Life.” George Bailey and his loving hometown of Bedford Falls are unmistakably on the side of the angels throughout, but for most of the narrative, Bailey is miserable. He longs to get out and see the world, only to find himself trapped by dull responsibilities back home.

Bedford Falls, meanwhile, is always just one turn of bad luck away from the garish, vice-ridden hell of Pottersville, where the ordinary folks are all prostitutes, drunks and gamblers. Though the greedy monopolist Mr. Potter serves as the film’s villain, all of his dastardly schemes depend on the people of Bedford Falls going along with them. Potter calls it a town full of “suckers,” and in his darker moods, Bailey agrees ― it’s just a “crummy little town.”

Pottersville was inspired by Reno, which served as Capra’s unlikely gateway into the movie industry. While still in his 20s, Capra’s roving grift operation brought him to W.M. Plank, a failed-actor-turned-gambler, and together they set out for the Nevada casinos to raise “sucker” money to shoot a cheap Western.

The Tri-State Motion Picture Company they formed with Plank’s lover Ida May Heitmann was mostly a scam. The company claimed to be capitalized at $250,000, even though it had only raised $1,000 when it began selling stock. But their Western eventually got made.

Afterward, Capra found work shooting one- and two-reel shorts for a fledgling startup in San Francisco, which bolstered his resume enough to get him a job writing gags for cheap Hollywood comedies. By 1927, he had directed his first feature, ”The Strong Man” ― one of the great comedies of the silent era, good enough to land Capra a job as a bona fide director at Columbia Pictures.

When Capra arrived, Columbia was a poverty-row operation that specialized in turning quick profits from B-movies made on the cheap, often packed into the second half of a double-feature. Within just a few years, he’d almost single-handedly transformed the studio into one of the most profitable and powerful operations in Hollywood.

By the time the Great Depression hit, Capra had seen everyman America. He knew what everyman America wanted to see and how to sell it. Throughout the 1930s, he churned out film after film about regular folks taking on corrupt elites and winning. In the process, he transformed a host of new faces into some of the most iconic figures from Hollywood’s Golden Age ― Gary Cooper, Barbara Stanwyck, Clark Gable, Jean Harlow, Jimmy Stewart, Jean Arthur and others. For a decade, he couldn’t miss.

Ho New/Reuters

Capra’s screenwriting partner throughout this remarkable run was Robert Riskin, a devout acolyte of Franklin Delano Roosevelt who preached the gospel of the New Deal to anyone in Hollywood who would listen. Capra’s own politics were more volatile. One day he was hanging a portrait of Benito Mussolini in his bedroom and citing Napoleon as his greatest hero. The next, he would declare all dictators his enemy and film a fictional villain next to a bust of the French conqueror. He never voted for FDR but experimented briefly with Marxism.

In short, he was perfectly attuned to the ideological mood of the country. From the other side of the Cold War, Americans are accustomed to understanding our government as a democratic middle-ground between right-wing fascist dictatorship and left-wing communist dictatorship. But the concrete surrounding these intellectual categories hadn’t yet hardened during the Great Depression. Plenty of FDR supporters saw no contradiction in their admiration for Mussolini, while others were enamored of the Soviet project. With the world crumbling around them, it wasn’t obvious what American life would look like after the Depression, if it would exist at all.

Capra’s regular-folk heroes always presented a deep-rooted, common-sense moral certainty to audiences, even as they endorsed all kinds of political doctrines with their dialogue. The combination in films like “Meet John Doe” or “Mr. Smith Goes To Washington” feels almost zany today. Capra’s films pay homage to Jeffersonian democracy as they celebrate aristocratic savvy. They offer fascist-adjacent masculine gusto and Catholic-Marxist exercises in liberation theology. For audiences in the Great Depression, it was a formula that felt like America.

With the world crumbling around them, it wasn’t obvious what American life would look like after the Depression, if it would exist at all.

World War II changed all of that. Eager to prove his patriotic bona fides, Capra signed up with the War Department and spent four years making propaganda films. By the time he got back to Hollywood, the Depression was over and the Cold War had begun. Major studios weren’t very interested in a director who hadn’t made a hit since 1941, and Capra had experienced a string of fallings-out with his old friends and colleagues. Some looked askance at his decision to work for the government, while others, particularly his longtime screenwriting partner Riskin, were tired of Capra’s inability to share credit for their work.

Capra started his new studio Liberty Films out of necessity. He couldn’t even score a distribution deal until he talked fellow director William Wyler into signing on with him.

“I can’t begin to describe my sense of loneliness in making that first film which we now called It’s A Wonderful Life, a loneliness that was laced by the fear of failure,” Capra wrote. “I had no one to talk to, or argue with.”

Capra felt enormous pressure to return with a major artistic statement. But he was keenly aware of how much the world had changed since the Depression, and simply didn’t know what he wanted to say about it. He took out his frustration on his screenwriters, replacing them in a seemingly endless cycle as he struggled to find the right narrative. Ultimately, nine different writers contributed to “It’s A Wonderful Life.” None of them enjoyed the experience.

His actors, by contrast, loved him. Jimmy Stewart jumped at the chance to work on another Capra film, regardless of what was going on with the script. “Frank,” he said, “if you want to do a movie about me committing suicide, with an angel with no wings named Clarence, I’m your boy.”

Not that every actor got star treatment. In his memoir, Capra recounted his search for “a young blonde sex-pot” to serve as “village flirt.” He wrote in his memoir that MGM’s casting director was “up to here in blonde pussies” and had introduced him to Gloria Grahame, who had been “snapping her garters” around MGM for two years. Grahame was still working in movies when Capra published the humiliating sequence.

Capra began raiding his old movies for ideas to salvage the script of “It’s A Wonderful Life.” Some of the most memorable scenes from the film are simply re-imaginings of prior Capra pieces. “Meet John Doe,” for instance, closed with a community of faithful admirers saving frustrated regular-guy Gary Cooper from suicide on Christmas Eve. If Gary Cooper could swing it, Capra thought, so could Jimmy Stewart.

Even Stewart’s character George Bailey was ripped from Capra’s 1932 film ”American Madness” ― in which a fiercely independent bank president bucked Wall Street interests to support local small businesses. In the process, his most loyal depositors saved him from a bank run by ostentatiously throwing their money into the faltering bank ― a scene that would be mined for two of the most powerful moments from “It’s a Wonderful Life”

“American Madness” had been an homage to A.P. Giannini, an Italian immigrant who founded Bank of America ― then a small California institution that specialized in loans to immigrants and small start-ups. Giannini was a New Dealer who backed FDR’s banking reforms as a check against his Wall Street rivals, and his politics made their way into speeches and monologues in both “American Madness” and “It’s A Wonderful Life.” Giannini had bankrolled Columbia Pictures, and when Capra started Liberty Films, he turned to him for money. “It’s A Wonderful Life” was a celebration of the man who financed it.

ASSOCIATED PRESS

As a result, lily-white Stewart was playing a composite of two Italian immigrants ― Giannini and Capra himself. Immigration wasn’t a live political issue in 1946. The country had effectively closed the door to families like Capra’s with the Johnson-Reed Act of 1924 because Italian immigrants were among the people considered less desirable than Anglo-Saxon Americans who set the country’s standard for whiteness, and most of the country had no interest in re-opening it. To many Americans, the idea that people born in Italy could ever really serve as their fellow citizens was ridiculous on its face. Some of the nastiest anti-immigrant sentiment was in Hollywood itself. John Wayne once attacked Capra by saying, “I’d like to take that little Dago son of a bitch and tear him into a million pieces and throw him into the ocean and watch him float back to Sicily where he belongs.”

But Capra wasn’t merely conforming to the demands of his time by whitewashing his cast. Stewart’s ambivalence about Bedford Falls in “It’s A Wonderful Life” reflected Capra’s own feelings about his immigrant background. In his personal quest for acceptance into the American elite, he very much wanted to leave his immigrant status behind. When Capra published his memoir in 1971, friends and family were outraged by the way he portrayed them ― nearly everyone from his childhood was illiterate or a rube.

And yet immigrants star in some of the most important sequences from “It’s A Wonderful Life.” When Bailey graces the servile, unthreatening Martini family with an affordable mortgage, the Martinis not only enter the middle class, they become financially baptized as full members of the Bedford Falls community. By the end of the film, the Martinis are among the parade of citizens who contribute to Bailey’s salvation. Even the Bailey family’s black housekeeper, played by Lillian Randolph, makes a donation. The white man who controls money is saved by the little people of his “crummy little town,” and all are elevated to divinity by the communal bond of their citizenship.

In his personal quest for acceptance into the American elite, Capra very much wanted to leave his immigrant status behind. And yet immigrants star in some of the most important sequences from ‘It’s A Wonderful Life.’

Though the film’s the climax takes place around a Christmas tree, the setting is a metaphor, not a marketing strategy. “It’s A Wonderful Life” opened nationwide in January, missing the Christmas season entirely. In 1946, the mass-market Christmas special hadn’t really been invented yet. The ephemeral nature of the movie business made it impossible to establish traditional favorites ― films were made, had their run, and disappeared from cultural existence. Not until the advent of television could the Grinch, Claymation Rudolph or ”A Charlie Brown Christmas” become annual favorites.

After its release, much of America wasn’t sure “It’s A Wonderful Life” was really appropriate for American families. Not only was Capra Italian, he’d been associating with radicals and liberals throughout his career. He’d even supported a directors union. To the red hunters of the late 1940s and 1950s, his was a dangerously subversive history.

Of the nine screenwriters who worked on “It’s A Wonderful Life,” seven would have their loyalty questioned by authorities, two would be formally blacklisted from work in Hollywood, and one, Dalton Trumbo, would be jailed for his refusal to cooperate with the House Un-American Activities Committee. The FBI compiled a massive report on communist influence in the motion picture industry, and concluded that screenwriters for “It’s A Wonderful Life,” had received “Communist support,” and that the film itself “deliberately maligned the upper class,” presenting a banker as a “scrooge-type” figure ― “a common trick used by Communists,” according to the FBI.

Capra was horrified by the inquisition. It was a physical manifestation of his deepest fear ― American officialdom threatening to rescind his hard-won American identity. When Congress and the FBI demanded proof of his loyalty, Capra complied by informing on some of his more radical Hollywood friends.

It didn’t help his career and took a terrible toll on his conscience. In 1951, Capra made the first of several suicide attempts. He made a few lackluster films during the ’50s, but even after retiring from the movie business, he never publicly acknowledged his cooperation with the blacklisters. The shame was too great.

Of the nine screenwriters who worked on ‘It’s A Wonderful Life,’ seven would have their loyalty questioned by authorities, two would be formally blacklisted, and one would be jailed for his refusal to cooperate with the House Un-American Activities Committee.

The best thing that ever happened to “It’s A Wonderful Life” was its financial failure. It performed badly enough that Capra sold Liberty Films in 1947, turning over the rights to all of the studio’s assets, including the negatives for “It’s A Wonderful Life.” By the time the film came up for copyright renewal in 1974, it had changed hands a few times, and its then-owner, RKO Pictures, forgot to file the paperwork.

As a result, “It’s A Wonderful Life” slipped into the public domain and became fodder for television producers seeking royalty-free entertainment. Seizing on its final scene, PBS began airing the film in Decembers to compete with glitzier, big-budget network Christmas specials. Eventually, the networks followed suit.

Even if “It’s A Wonderful Life” didn’t run away with ratings, a production cost of $0 was hard to beat. By the mid-1980s, courtesy of the cold-eyed calculation of a new generation of television executives, “It’s A Wonderful Life” was reborn as a piece of spiritual Americana, spoofed by Saturday Night Live, colorized and submitted to other indignities of American commerce.

“It’s the damnedest thing I’ve ever seen,” Stewart told The Wall Street Journal in 1984. “The film has a life of its own now …. I didn’t even think of it as a Christmas movie.”

In the 21st century, “It’s A Wonderful Life” retains its power because it doesn’t offer easy answers. Sure, the plot is salvaged by a deus ex machina, but Bedford Falls never loses its provinciality. It’s a crummy little town from start to finish. The people who believe it can be something better just decide to make the best of it that they can. Like everything profound, the message is a platitude if you say it the wrong way. Capra found the magic to make it beautiful.

[ad_2]

Source link