[ad_1]

The four-hour documentary “Leaving Neverland,” which left the audience stunned at last week’s Sundance Film Festival premiere, presents an unimpeachable perspective on Michael Jackson’s alleged child sexual abuse, effectively capsizing the pop icon’s already complicated legacy.

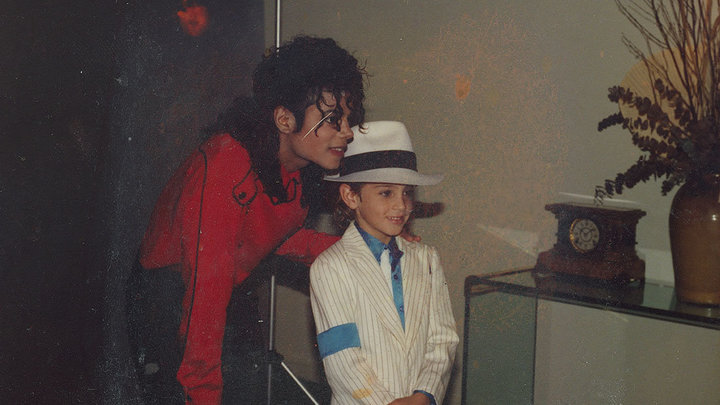

Director Dan Reed’s film centers on two men, Wade Robson and James Safechuck, who as kids were inducted separately into Jackson’s inner circle under the guise of artistic mentorship. Robson, who went on to choreograph tours and videos for Britney Spears and ’N Sync, was 7 when he met Jackson through a dance competition; Safechuck, who was cast in a Pepsi commercial starring Jackson, was 9.

What really happened with the acclaimed singer, Robson and Safechuck say, was a gradual predation that introduced the boys to kissing, pornography, masturbation, oral sex and more. Over the course of several years, beginning in 1987, Jackson allegedly ingratiated himself with Robson’s and Safechuck’s families, so much so that he deluded their mothers into thinking that it was an innocent gesture of friendship for him to share a bed with their young sons. Once they passed puberty, Robson and Safechuck now say, Jackson cast them aside for younger boys, leaving them confused and devastated.

It wasn’t until their 30s that Robson and Safechuck, who met only briefly as children, came to realize that their respective experiences amounted to life-altering assault.

“Leaving Neverland,” which will air on HBO in early spring, is split into two parts. The first details Robson’s and Safechuck’s experiences, including the perspectives of various relatives who knew Jackson during that period and assumed he was a harmless, lonely superstar with a childlike persona. The second chronicles the lingering trauma of Jackson’s alleged misdeeds and the way it has torn apart Robson’s and Safechuck’s adult lives. Their accounts of sexual abuse are among the most specific and heartbreaking to emerge in the Me Too era.

That hasn’t stopped Jackson’s family from calling “Neverland” a “public lynching,” nor has it deterred the many hyperloyal Jackson fans who have launched a crusade to discredit the documentary, sight unseen. Reed, who said at the Sundance premiere that Robson and Safechuck were not compensated for their participation, stands behind the allegations that surface in the film.

I sat down with Reed, whose credits include “The Pedophile Hunter” and “Frontline Fighting: Battling ISIS,” at the festival to discuss Jackson’s legacy, Reed’s corroborating research and how our elementary understanding of sexual misconduct leaves some people unable to see Jackson as anything but a masterly entertainer.

When you started working on this film, how cognizant were you ― and how cognizant are you now ― that Michael Jackson is almost inarguably the most famous, celebrated and beloved of the many men who have faced misconduct allegations in the past couple of years?

Right, right. I wasn’t a Michael fan when I was a kid, and I didn’t really listen to pop music. So in many ways, I was kind of agnostic about Michael. I think he’s an excellent entertainer ― there’s no denying that ― and he achieved a level of stardom that perhaps no one would ever be able to again. Right time, right place, right guy. So I wasn’t particularly intimidated by the stature of Michael. I was really focused on these two guys and their families. In the story, Michael is a peripheral character. He’s an important character, but he’s in the background, and you learn a little bit about him, but it’s not a film about Michael Jackson.

I’m realizing now the magnitude of his influence and how many people adore him, how he’s woven into the fabric of so many people’s lives. [Now we’re] challenging his reputation, and we’re not the first [people] to do it. But I believe that this film has a completeness and a credibility that hasn’t been matched before. This is really the first time that survivors of child sexual abuse and Michael have spoken out. So I knew that would be a big thing for the world to take in. …

I wonder how people will react and how they’ll accommodate the knowledge that they will get from watching our four-hour film, if they make that journey and how they will reconcile that with their love for his music. I don’t know the answer.

Was it always clear to you that the film would not be an adjudication of Jackson’s entire cultural legacy? Lifetime’s R. Kelly series, for example, dissects his lyrics and childhood conditions. Jackson’s young fame is well documented; we all watched the famous Jackson 5 miniseries in the 1990s. Did you ever consider including more about his legacy and about his life before 1987?

I did, but very briefly, and I quickly came to the view that that wasn’t the way forward for me. Michael’s dead. I can’t interview him. I don’t have any way of directly addressing some of the issues raised by Wade’s and James’ interviews. I don’t know why he did things he did, and I don’t feel I have the authority to speculate on that.

And that’s a matter for another movie. That’s a matter for another time when perhaps people around him and people who worked with him at the time of this story might come to terms with the reality of what actually happened, which I think people are trying to now, maybe. So the movie is focused very narrowly on, I’ll say again, the story of these rather ordinary individuals. They weren’t part of the Jackson phenomenon. Wade had a career in show business, but at the time when they met, he was a 7-year-old boy, and his dad had a small grocery store. And James’ dad worked in a rubbish collection company. These were not celebrities.

So I didn’t see a connection between Michael’s music and his pedophilia. I can’t make that connection. The film very humbly just focuses on what we know and tells a story about people I met and people who were willing to go on camera very bravely, and that’s where it stops.

The other thing that sets the Jackson story apart from most of the other stories of men who have faced recent allegations is that he’s dead and cannot speak for himself. How did that factor in?

Michael’s views about this story ― his refutations and his statements ― are included in the film. The views of his lawyers who defended him in the criminal trial [in 2005] and who defended him in the ’93 civil case are prominently featured in the film. So it’s not as if there are no voices defending Michael in the film.

I believe, had Michael still been alive, his lawyers would’ve said similar things — “It’s all about the money.” That’s been their main line of attack, always characterizing the accusers as gold diggers. I don’t think it’s true to say that he’s dead and he can’t say anything. Well, that’s literally true. But we have gone to some pains legitimately because it should be represented in the film to have Michael denying the ’93 and the 2005 allegations to say, “I love children in an appropriate way.” Did he believe that he was harming children? I don’t know. Maybe he didn’t. Maybe to him, he wasn’t harming children. And therefore when he makes that statement from Neverland and says, “I would never harm a child,” maybe he believes it.

So I think Michael is in the film, and he speaks for himself, and his lawyers speak for him, and his fans speak for him. We’ve got that, a couple of fans [in archival footage saying], “Wade, I hate you.” So I do think that, in spite of the fact that he’s dead, we’ve done our very best to include him in everything ― and include him not in a token way but in a way that really pushes back against the allegations we make.

In the film, members of Jackson’s staff are mentioned in various contexts, specifically a personal assistant, a secretary and a housekeeper who had contacted the families on Jackson’s behalf or encountered them during that period. And obviously, he also has a network of very well-known siblings. How many of them have you spoken to? Did you consider including any of their accounts in order to corroborate more of the specific claims for those who are eager to poke holes in the information being presented?

I didn’t consider, as you mentioned, his family, because this is a film about the sexual abuse of James Safechuck and Wade Robson. People with no direct knowledge of that story or of those events don’t have a place in the film. They’re welcome to speak out, as they are doing now. But I do not see why I should include people who cannot possibly know the truth of what happened with this child.

As regards to the investigators and people who were involved or witnesses from the households, I did contact a few people and read many, many statements. In the two big investigations around Michael, there’s a wealth of recorded material, legal documents and what have you, which I explored very thoroughly. Many of them are actually available online. And I also reached out to a few major investigators ― DAs and what have you ― and members of the household. And some of them have passed away, actually, since the court case. Usually what they had to contribute was, “I glimpsed this,” “I saw Michael and James in the Jacuzzi together, and they appeared to be naked,” “I saw Wade and Michael in the shower,” “I picked up Wade’s underwear,” that kind of stuff ― which kind of obliquely corroborates, I suppose, Wade’s and James’ stories.

I never found a single investigator who didn’t think Michael was guilty, and I never came across anything at all that led me to doubt either Wade or James.

There’s an awful lot of circumstantial corroboration, but what we have in the story is from the horse’s mouth. We have the child speaking about what happened to him, and I didn’t know how much more credible it would appear if I have a maid going, “Well, yeah, I saw Wade.” Some of these accounts were challenged by Michael’s lawyers in court anyway, and in a very general way, the tabloid frenzy around the story at the time. The payments that were made to various members of the household slightly tainted that whole dimension of the story, in my view and I think in many people’s eyes.

So I wanted to stay clear of that and base myself on a very consistent, credible set of accounts of two decades of these families’ stories. We spent months looking at the old documents, everything that was published, conversations with investigators. I never found a single investigator who didn’t think Michael was guilty, and I never came across anything at all that led me to doubt either Wade or James. Over the last 30 years, I’ve built a reputation as someone who’s uncompromising about telling the truth. Why would I embark on a journey to hang my reputation on the story if I thought it was even in a tiny way flawed? So everything had to be really, really solid. I feel I’ve done a very diligent and thorough job.

I agree with you. Everybody I’ve spoken to agrees with you. But as I’ve witnessed on Twitter in the past few days, a lot of people are not going to agree with you. I’m also not convinced that a lot of the people who are making those preconceived conclusions will come around, even if they were to see the film. Our understanding of sexual trauma is still so rudimentary.

You’re absolutely right, and that’s one of the things that we set out to address. I won’t say this film is an attempt to educate the public about child sexual abuse, but I hope it does.

But for those who are so eager to not believe because they are staunch Jackson loyalists or because they do not understand the idea that somebody years ago could have said, “He did not abuse me,” and then later realize that it was abuse …

It’s very typical, but most people don’t know that, and some Jackson superfans won’t accept that. Are you mindful of the fact that, because there is limited corroboration, as we see it, in these four hours, people will still refuse to believe and refuse to understand the epidemic behind the ideas that are in the documentary?

Yeah, I think the two big things that people don’t understand about child sexual abuse: One, they don’t realize that not always but oftentimes the relationship mirrors an adult relationship in terms of [being] a love relationship. The child falls in love with his abuser. And they form a very close emotional attachment that has many dimensions. The abuser is a mentor; a father figure, as Michael was; a dazzling supernova of talent, as Michael was; and a sexual partner. And the child falls in love with that and all those good things. There are many good things about Michael.

Robson and Safechuck do start by saying that he was one of the kindest and most gentle people they knew and that this began as the happiest experiences of their lives.

Yeah, so I’m not taking a baseball bat to Michael Jackson. I’m telling a story from the point of view of the child. Now, people do need to understand that these [might have had the character of] romantic relationships, but [were actually] criminal ones, and that what powerfully motivated the child was the desire to continue the relationship and to be loved by Michael. They felt chosen, they felt anointed. He made them feel very special, and that was an amazing thing. And that feeling continued for a long, long time, until his death and past it ― even long after the sexual relationships were finished. And so that love, the deep emotional attachment to Michael, is something that I think the fans don’t understand. And that motivated Wade to lie in defense of Michael [in the 2005 trial] and to the detriment of a child [Gavin Arvizo] who had the courage to stand up in a court. That’s a big decision to make, but Wade made it.

And in terms of the abuse only being recognized by the victim or divulged by the victim years later, that is so typical. I spoke to one of the investigators in the 1993 case that the LAPD had begun investigating, a criminal investigation against Jackson, which of course never went to trial. He’s a man who is retired now. He’s been involved in more than 4,000 child sexual abuse investigations. He said Jackson’s modus operandi was absolutely typical, and the fact that Wade and James only came to terms with what happened to them and understood it in its true context much later in life is also very typical. And in fact, one of the detectives who came to see the Safechucks at the time in the early ’90s, when they were denying that anything happened and saying Michael’s wonderful, said, “You know what? Your son’s going to come back to you when he’s in his 30s, and he will say, ‘Michael abused me.’”

Do you feel like you have some sense of the totality of Michael’s alleged abuse? There are a couple of other potential survivors mentioned in the film who are not participants and others who still deny that what they experienced is abuse. Obviously, the implication is that we have no idea how many others there could have been.

Yeah, Jordan Chandler and Gavin Arvizo made legal complaints against Michael, so that’s established. They both still stand by those allegations. There are little boys at the time who, along the years, spent many nights in bed with Michael, and that’s an established fact. Did he molest them? I don’t know. That’s for them to say. We’re not in the business of outing anyone. And if they were molested, they’ll come to terms with that in their own time. But the fact is that Wade and James were replaced in Michael’s affections, sexually or not, by other boys [like Macaulay Culkin and Brett Barnes] who had this outwardly similar type of relationship. I cannot speak to whether there was a sexual dimension or not. They’ve both denied it categorically and vehemently in the media and continue to deny it. Do I think there were many others? Yes, I do. Who were they? I’m not going to name names.

Did you speak to others whose names you cannot name?

I did speak to one other, yeah.

And that person recognizes that it was abuse?

But does not want to speak publicly about it.

Yes, didn’t want to go on camera.

If you’d only had one participant ― in other words, Robson or Safechuck but not both of them ― would you still have made the film? Does it require at least two accounts?

I say this not to question either of their individual experiences, but one of the most impactful things in the documentary is the way their stories align. They both experience the same progression of sexual acts, in similar contexts and circumstances, even though they didn’t know each other until now.

Yeah, that’s a good question. And without the moms, was there a film? As a documentary filmmaker, I’m involved in this really long-form filmmaking, which requires so many elements and so many different angles in story form, because the stories are always told in a sort of intimate register, through characters and personal experience. That’s why I like to tell the big stories through individual experience and individual testimony.

So if a piece of that is missing, that’s my nightmare. To have a potentially amazing film and have one key person who’s missing, that keeps me awake at night, and it terrifies me. But somehow up to now, I’ve pretty much always managed to get most of the people I need to film. So to answer your question, would it have been a film without the two of them? I think it would’ve been a weaker film.

To what degree does that leave you working to get a third account so that the film is even more unimpeachable? I ask that knowing it can’t be easy to make a sexual trauma survivor feel comfortable and agree to give you his time and mental capacity.

Yeah, well, I think if we’d had a third family, it would’ve been a six-hour film. Maybe that’s pushing it a bit too far. I think the completeness of their stories works very well in this case. For me, it’s very persuasive, and I think it was for the audience at the premiere screening.

The story that I think remains to be told ― and the story that I’m kind of fascinated by but would depend on Jordan Chandler and Gavin Arvizo taking part ― is the story of how those cases went down and what happened. It’s the inside story of those two cases — the civil case in ’93 and the criminal case in 2005, because that’s fascinating. Because the 2005 criminal case was a world event, on a massive scale.

It was conducted entirely in the public eye, with all the cameras in court. And how was it that this child who testified very clearly to sexual abuse at the hands of Michael, how come he wasn’t believed by the jury? And what happened behind the scenes? There’s a lot we don’t know, but that would speak more to the interaction between law enforcement and the public. I think it’ll be a fascinating film to make, but I think both Jordy and Gavin would have to come forward and allow themselves to tell their story.

What kind of legal vetting did this film require? Did lawyers look at the finished cut before any of the public saw it?

Every film I make is, obviously, it’s not vetted, but it’s watched and commented on, and we operate very carefully and want to make sure that everything we say is sound and good to be broadcast.

And when you say “watched and commented on,” what do you mean? Specifically, do you have an attorney who sits with the film and tells you what is or isn’t OK to include?

That’s what happens on every single film I make or, to my knowledge, that anyone makes, certainly for HBO or BBC. There’s a lawyer who was involved in an advisory capacity. He doesn’t tell us what to do but advises us on this or that and particular ways of articulating a story.

That’s completely routine, and if your question is “Has this film required more lawyering than any other documentary that I’ve been on?” no. Because for better or worse, most of the documentaries I make require the careful and regular attention of lawyers. That’s just the way it is.

The toughest part of this documentary is listening to the details of the alleged abuse, which become increasingly graphic across the first two hours. We see a pattern of abuse and manipulation ― whether or not Jackson saw it that way ― unfurl. Did you ever have any reservations about how graphic the details needed to be so that we could, on the one hand, understand the situation and, on the other hand, be able to sit with the information?

Yeah. I thought a great deal about that, and it actually preoccupied me a lot. This is not a salacious documentary. I don’t think the descriptions of the sexual acts in it are in any way titillating or prurient. And this was something I said to Wade and James before we did the interviews. I said, “We have to go there, and you have to tell me what he did in as much detail as you can, and I promise to treat your accounts with respect. But we have to be explicit because we have to establish that what happened to you was not affectionate intimacy.” It was not the brushing of lips on the cheek or a cuddle that sort of was a bit too tight or an embrace that was a little too long.

It wasn’t just holding hands in a crowd, as we see at one point.

No. It was sex. And that’s why we had to include those bits. Now, dosing it, if you like, and deciding how much an audience can take before they go, “Oh, my God, I don’t want to hear any more of this,” that’s a matter of judgment. And I hope I got it right. We could’ve included more, we could’ve included less. It will vary from person to person. Some people will just go, “I can’t hear this,” and others will find it revealing because [you say], “OK, so that really did happen. There’s no other way of describing it than sex.”

So, yeah, it’s a judgment that I hope I got right. And you guys will be the judge of that, really.

To the degree that the Jackson family and the crazy Jackson fan base is now engaging, sight unseen, with the film and the content in it, how interested or willing are you to engage with them? Are you interested in conversing or trying to help them see the possible error of their judgments? Or do you have to say, “The film stands alone. I step aside”?

Very much the latter. I mean, the film speaks for me.

The story is complex. That’s why you need four hours to tell it. I have no claim to correct the views of the Jackson family. They love Michael. They’re defending him. That’s not unexpected. The estate is a huge source of wealth and income, and they will defend themselves. That’s also to be expected, so that’s entirely normal, and I’m not here to have any kind of argument with the Jackson family.

I do think that if the last couple of years have taught us anything, it’s that we need to pay close attention and really listen to the stories of victims of sexual abuse. We shouldn’t try and shame the victims of sexual abuse. I don’t know whether the family’s and the estate’s first instincts is to listen.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

A small update has added to Reed’s response to clarify a point of unclear syntax.

[ad_2]

Source link