[ad_1]

“I introduce myself here, because in the story I’m about to tell, I begin with no name or identity.”

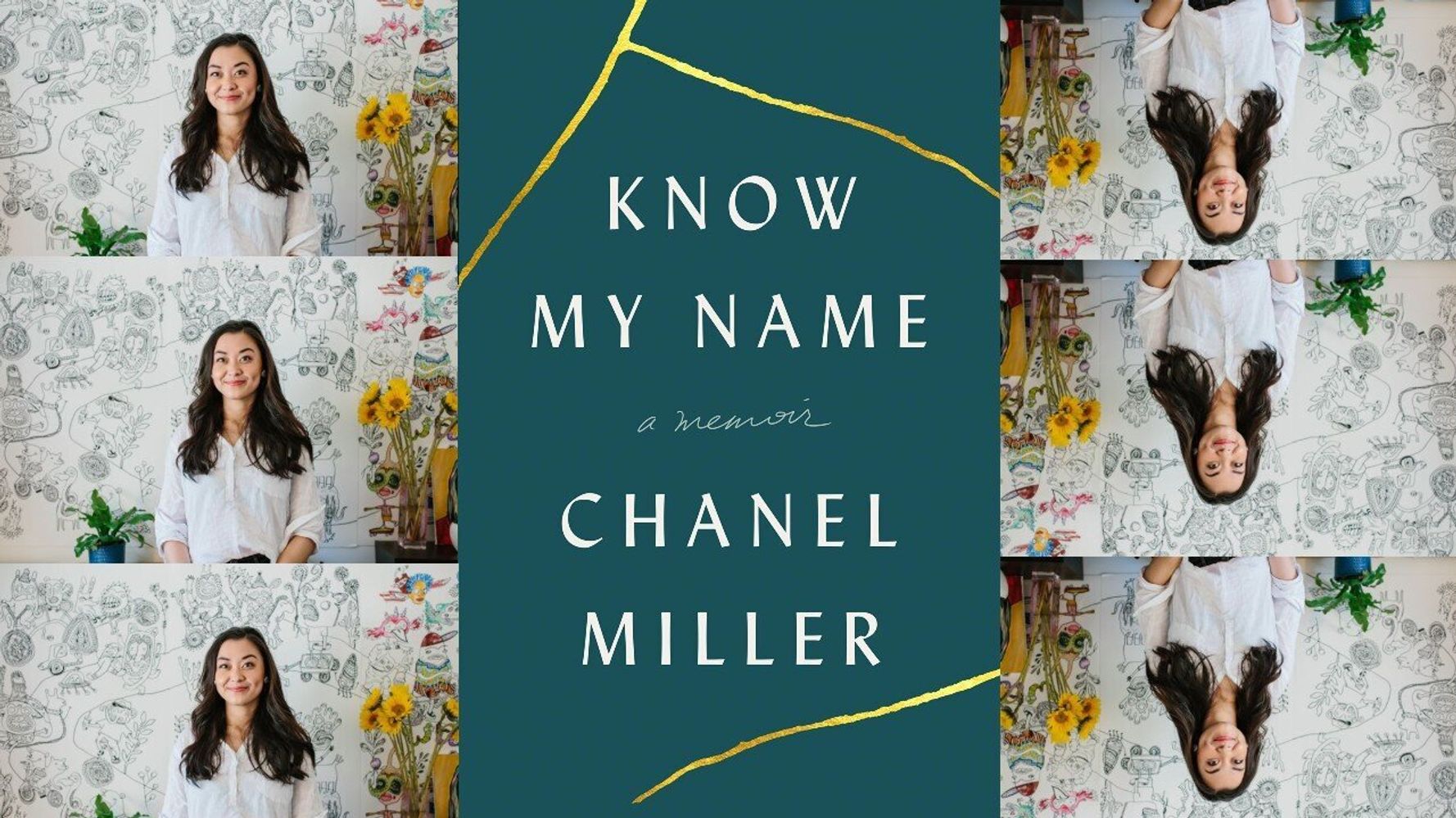

So writes Chanel Miller on Page 2 of her memoir, “Know My Name.” Chanel Miller — it feels important to write her full name more than once because the public spent years talking about her without it — went to a party at Stanford University in 2015 and ended up in a hospital, unsure how she had gotten there. She would soon learn, by way of cryptic statements by law enforcement and, eventually, local news coverage, that she had been sexually assaulted behind a dumpster while unconscious by a 20-year-old Stanford student named Brock Turner.

You probably know the vague outlines of the story from there: Turner was found guilty of multiple felonies, including assault with intent to rape an intoxicated woman. He was sentenced by Judge Aaron Persky to six months in county jail, of which he would serve three. His victim, known then only as Emily Doe, wrote a searing victim impact statement, which was published on BuzzFeed and read on live TV, on the floor of Congress and by millions online. Persky was recalled. Turner was released from jail. Laws were changed.

What you are less likely to have is a clear picture of Miller: her background in art, the way that writing runs in her family, her loving sister, the way she read all of the comments on the news coverage of her assault, her rage, her desire, her potential. With “Know My Name,” Miller gets to reclaim her humanity.

There is an instinct to lionize survivors of sexual assault who are brave enough to share their stories, to put their experiences up on a pedestal for the edification of the larger culture. That instinct makes sense. In a culture that makes it nearly impossible for survivors to get justice or even be believed, we want to find meaning in tragedy made public. But to turn a survivor into a symbol, a lesson, a one-dimensional inspirational quote, is to flatten them and deprive them of their humanity. It is a particular cruelty to be defined by the worst thing that ever happened to you, and to exist in the public sphere only in relation to it. This is one of many injustices that Miller’s memoir seeks to right.

Chanel Miller just wants what was always afforded to Brock Turner: to be viewed as a human being.

In our collective memories, we like to freeze in time women who become publicly identified victims, as though they were born only as their alleged assault was enacted and ceased to exist as soon as their stories stopped being front-page news. Christine Blasey Ford did not stop existing after Brett Kavanaugh was confirmed to the Supreme Court, and her story mattered before he entered her life. Her story did not stop being written, her wounds were not healed, her complexities were not diminished. The same goes for Andrea Constand and Aly Raisman and Emma Sulkowicz and Kyle Stephens and every person who has experienced a sexual trauma, regardless of whether it is made public.

“I did not come into existence when [Turner] harmed me,” Miller writes. “She found her voice! I had a voice. He stripped it, left me groping around blind for a bit, but I always had it … I do not owe him my success, my becoming, he did not create me. The only credit Brock can take is for assaulting me, and he could never even admit to that.”

Miller has an almost inconceivable well of perspective on her experience. She writes about the way that her relative anonymity allowed her statement to feel almost universal. Instead, she was allowed to become “the lady with the blue hair, the one with the nose ring. I was sixty-two, I was Latina, I was a man with a beard. How do you come after me, when it is all of us?”

As women in a culture that does not respect us — one that views our bodies alternately as public property and private objects that should be obscured from view and “protected” from impurity — we pretty much all have a story. After Miller’s statement was published on BuzzFeed, I spoke to countless women who saw themselves or their loved ones in her words. Her words did not fade from public memory, because they were not attached to one face, one life that could be picked apart and mined for stereotypes and imperfect victimhood.

Miller’s memoir also articulates the way that sexual assault has ripple effects far beyond just the victim. So many of us have been counselors and confidants, holding our friends’ pain the way that Miller’s sister and parents and friends did. We wonder if we had just stayed at that bar an hour longer or just been more vigilant at that party, if we could have prevented irreversible damage perpetrated by someone who felt entitled to the bodies of our loved ones.

When a story of sexual trauma becomes national news, there is a temptation to paper over the complexities in favor of a Big Uplifting Lesson. In a world of constant updates and 24-hour news cycles, we have become accustomed to reading a headline and moving on. We prefer stories that are digestible, stories with clear-cut, one-dimensional heroes and villains, stories that provide a pat lesson that allows us to believe that our work here is done. But healing is not linear, nor is it quick, and neither is real, lasting social change. And it is not the responsibility of survivors to make their pain and recovery more palatable to the masses.

Toward the end of the book, Miller describes a protracted tug of war with Stanford over a plaque that was to be placed at the scene of her assault, now a small garden with two benches. There was supposed to be a plaque engraved with a quote from Miller’s victim impact statement, but Stanford would not approve any of the passages she suggested, because they were not uplifting enough.

It is not the responsibility of survivors to make their pain and recovery more palatable to the masses.

“As a survivor, I feel a duty to provide a realistic view of the complexity of recovery,” Miller writes. “I am not here to rebrand the mess [Turner] made on campus. It is not my responsibility to alchemize what he did into healing words society can digest. I do not exist to be the eternal flame, the beacon, the flowers that bloom in your garden.”

Chanel Miller just wants what was always afforded to Brock Turner: to be viewed as a human being, with likes and dislikes and communities surrounding her and pain and potential. At one point in the book, Miller wonders if Judge Persky and others who bemoaned all that Turner would lose if he faced significant legal consequences, saw her as “frozen” in those 20 minutes of victimization.

“She remained frozen,” Miller writes, “while Brock grew more and more multifaceted, his story unfolding, a spectrum of life and memories opening up around him. Nobody talked about the things she might go on to do.”

But Miller also understands that the best way to go from headline to human is to write about and speak about your own story in your own words on your own terms. “Know My Name” is a memoir, yes, but it’s also a heart-wrenchingly honest manifesto for any survivor.

“The barricades that held us down will not work anymore,” Miller writes. “And when silence and shame are gone, there will be nothing to stop us. We will not stand by as our mouths are covered, bodies entered. We will speak, we will speak, we will speak.”

Perhaps the world is finally ready to start listening.

Need help? Visit RAINN’s National Sexual Assault Online Hotline or the National Sexual Violence Resource Center’s website.

REAL LIFE. REAL NEWS. REAL VOICES.

Help us tell more of the stories that matter from voices that too often remain unheard.

[ad_2]

Source link