[ad_1]

Installation view of Ivan Seal and the Caretaker’s “Cukuwruums” at Unsound Festival.

COURTESY THE ARTISTS

In Krakow, Poland—through a portal past a tacky souvenir stand and into the bowels of an abandoned building that dates to the 14th century and has more recently played home to a shuttered bingo parlor and a shady nightclub from the years after communism fell—an exhibition by the painter Ivan Seal blurred the boundaries between art and everything else. It was on view for only a week—in early October as part of Unsound Festival, a gathering for exploratory sound and art-related corollaries—but it stands to have a future still, in the context of concerts by the enigmatic electronic-music-maker known as the Caretaker.

Seal and the Caretaker have a history. Both are from England and spent time together in Berlin, and they collaborated on a number of record covers for a project that just wrapped up with a six-album series devoted to thinking through memory loss and dementia. Music by the Caretaker (whose name is a nod to a spectral character in the 1980 Stanley Kubrick film The Shining) tends toward technologically altered reminiscences of the old-fashioned, with sounds of vintage ballroom waltzes and parlor tunes from 1930s-era 78-rpm records edited and processed into simultaneously straightforward and ghostly lull. And paintings by Seal tend toward the uncanny, with a representational simplicity locked in a tense duel with a habit for seeming to always be silently thinking out loud. Together, their work in different mediums found a match.

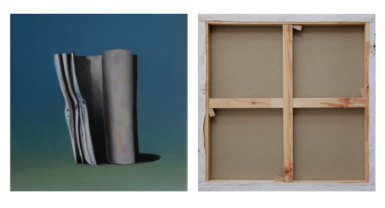

Record cover, front and back, for the Caretaker’s 2016 album Everywhere at the End of Time.

COURTESY HISTORY ALWAYS FAVOURS THE WINNERS

The Caretaker’s albums each feature a painting by Seal on the front cover and a verso view of its frame on the back—with the vinyl LP slipped in between, all as one sort of intermedia object. The paintings have lived other lives as well, including in “Everywhere, an empty bliss,” an exhibition credited to Ivan Seal and the Caretaker (also known as James Leyland Kirby) earlier this year at Le Fonds Régional d’Art Contemporain Auvergne in France.

In Krakow, they staged something more impressionistic in a space whose singularity could not be overstated. In the city’s Gothic Old Town center, their desire for empty rooms paid off when the organizers of Unsound—searching for the kind of surprising and strange venues that have long been a mainstay of the festival—found a sprawling network of them on a former apartment floor that seemed to have gone untouched and left to wither and fade for decades.

“I didn’t want to do a gallery show—I wanted to do something different, in a different space, and this space had cigarette packets with a layer of dust, a bit of either human or animal excretion, an old newspaper from 2014,” Seal recalled of rooms also dotted with sheets of exposed insulation and planks of wood that had fallen down. “I said nothing should be cleared up—there would be no brushing up.”

Installation view of Ivan Seal and the Caretaker’s “Cukuwruums” at Unsound Festival.

COURTESY THE ARTISTS

Seal was speaking during a panel discussion at Unsound along with the Caretaker and video artist Weirdcore, who worked on visuals for a musical performance at the festival that activated the paintings in another way, with footage from a walkthrough of the exhibition edited and abstracted live on a giant screen behind a stage in a cinema. (Weirdcore also works on concert visuals for the English electronic musician Aphex Twin and makes video work of other kinds.)

Concerts are rare for the Caretaker, an idiosyncratic showman who, during the panel (which was presented by ARTnews), regaled the audience with a tale of once having secured two turntables at an electronic-music festival in Spain only to cover each with a head of cabbage that spun round and round. But this appearance, marking the end of his album-series project in his adopted hometown of Krakow, would be different—and the pop-up painting exhibition played an integral role in making it more than just a musical affair.

Ivan Seal, nopossibiseallityarv leevin, 2019.

COURTESY THE ARTIST

The paintings in the exhibition were separate but related to the ones on the record sleeves. The 12 new works were created for the space they would hang in, to be set in nooks and corners in the voluminous dilapidated environs. “The idea was that each painting would be small, and each would have something on it that looks like it’s been hung on a wall,” Seal said. “So the only thing that does not belong to the space is the canvas and the frame”—the aspects of a painting that make it a painting in the end.

Seal likes paintings that flirt with other forms. About the record covers that are paintings in every way but the most essential one, he said, “Each record is pretending to be a painting—it’s not a painting, it’s a record sleeve. So we make it pretend by putting the back of the painting on the back of the sleeve. Then on the side you have my name, the title, and a gallery reference.” (Seal is represented by Carl Freedman Gallery in Margate, England, and Galeria Monica de Cardenas in Milan, and the Caretaker’s name does not appear anywhere on the exterior of the record sleeve at all.)

Seal also titles the paintings in perplexing ways that tend to abstract them even further. “I go online to easily accessible nonsense-word generators and then sit and churn out nonsense until one is fitting for the painting,” he said. “It’s then what that thing is.”

Titles like nopossibiseallityarv leevin, volvings trolixotes viroes, and adoueticanced frequidist can evoke nothing and everything at once. “It’s the same as how we got to words like ‘jug’ or ‘cardigan’ or ‘people,’” Seal said of mantles might be arbitrary and can also start off feeling wrong but strike as right with time. “The process is one that sets up red herrings within the piece of art and creates something that Umberto Eco wrote about in The Open Work: the idea of an open field of interpretation. It has more potential for meaning the closer it gets to a threshold of noise. The more something gets close to noise, the more meaning is possible. With something like an oil painting, with such a set of parameters and a certain history, if you look at it, you expect something of it—so it’s a responsibility to put in avenues which can fuck with that system.”

Titles like nopossibiseallityarv leevin, volvings trolixotes viroes, and adoueticanced frequidist can evoke nothing and everything at once. “It’s the same as how we got to words like ‘jug’ or ‘cardigan’ or ‘people,’” Seal said of mantles might be arbitrary and can also start off feeling wrong but strike as right with time. “The process is one that sets up red herrings within the piece of art and creates something that Umberto Eco wrote about in The Open Work: the idea of an open field of interpretation. It has more potential for meaning the closer it gets to a threshold of noise. The more something gets close to noise, the more meaning is possible. With something like an oil painting, with such a set of parameters and a certain history, if you look at it, you expect something of it—so it’s a responsibility to put in avenues which can fuck with that system.”

For the exhibition, titled “Cukuwruums,” the stillness of the abandoned building was suffused with only one addition beyond Seal’s paintings: the Laurel and Hardy theme song as reconceived in a slow, otherworldly version by the Caretaker playing on a tiny speaker on the floor. And then, when the Caretaker performed at the festival in a cinema that seats more than 800, Seal joined him as a curious character sitting in one of two easy chairs in the middle of the stage. Between them was a bottle of whiskey that the Caretaker would occasionally wander over to toast and sip.

“The first time I was on stage sitting was at the Barbican Centre,” Seal said of a similar Caretaker performance presented by Unsound in London in 2017. “It’s interesting when people are together in a loose sort of way. There was a bottle that we drank in front of people for 40 minutes, and I realized it was a spirit. So there were three spirits on the stage…” And the extra spirit between the Caretaker and Seal came to embody an old friend of theirs who had died months earlier: Mark Fisher, the cultural theorist and writer whose numerous books include Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? (2009), Ghosts of My Life: Writings on Depression, Hauntology and Lost Futures (2014), and The Weird and the Eerie (2017).

Installation view of Ivan Seal and the Caretaker’s “Cukuwruums” at Unsound Festival.

COURTESY THE ARTISTS

With two concerts of the kind in the rearview, the plan is to present more to mark the end of the Caretaker project as a whole. (Kirby also works under other aliases including V/Vm and the Stranger, as well as his own name.) And if the right setting presents itself—ideally as abandoned, empty, and evocative in some certain way—the aim is to restage the exhibition in popup forms around the performances.

For Seal, the most significant consideration is that the space be able to harbor the presence of paintings as a sort of surprise. “If you’re walking around, you may come across a painting,” he said of the exhibition in Krakow, “whereas in a gallery you look for them straight on. I wanted the paintings to subvert the space so that it’s questionable whether all of it might be a painting, somehow. You don’t know what is art or not—that is key.”

[ad_2]

Source link