[ad_1]

I can’t tell you about a specific day as a cable tech. I can’t tell you my first customer was a cat hoarder. I can tell you the details, sure. That I smeared Vicks on my lip to try to cover the stench of rugs and walls and upholstery soaked in cat piss. That I wore booties, not to protect the carpets from the mud on my boots but to keep the cat piss off my soles. I can tell you the problem with her cable service was that her cats chewed through the wiring. That I had to move a mummified cat behind the television to replace the jumper. That ammonia seeped into the polyester fibers of my itchy blue uniform, clung to the sweat in my hair. That the smell stuck to me through the next job.

But what was the next job? This is the stuff I can’t remember — how a particular day unfolded. Maybe the next job was the Great Falls, Virginia, housewife who answered the door in some black skimpy thing I never really saw because I work very hard at eye contact when faced with out-of-context nudity. She was expecting a man. I’m a 6-foot lesbian. If I showed up at your door in a uniform with my hair cut in what’s known to barbers as the International Lesbian Option No. 2, you might mistake me for a man. Everyone does. She was rare in that she realized I’m a woman. We laughed about it. She found a robe while I replaced her cable box. She asked if I needed to use a bathroom, and I loved her.

For 10 years, I worked as a cable tech in the Virginia suburbs of Washington, D.C. Those 10 years, the apartments, the McMansions, the customers, the bugs and snakes, the telephone poles, the traffic, the cold and heat and rain, have blurred together in my mind. Even then, I wouldn’t remember a job from the day before unless there was something remarkable about it. Remarkable is subjective and changes with every day spent witnessing what people who work in offices will never see — their co-workers at home during the weekday, the American id in its underpants, wondering if it remembered to delete the browsing history.

Mostly all I remember is needing to pee.

And I remember those little glimpses of the grotesque. I’ll get to Dick Cheney later. The one that comes to mind now is the anti-gay lobbyist whose office was lined with framed appreciation from Focus on the Family, and pictures with Pat Buchanan and Jerry Falwell, but whose son’s room was painted pink and littered with Barbies. The hypocrite’s son said he was still a boy. He just thought his sundress was really cute. I agreed, told him I love daisies, and he beamed. His father thanked me, and I wanted to tell him to go fuck himself. How the fuck do you actively work to ensure the world’s a more dangerous place for your beautiful little kid? But I didn’t ask him that. I just stood and glared at him until he looked away. I needed the job. I assumed his kid would grow up to hate him.

Maybe the next job that day was the guy whose work order said “irate.” It’s not something you want to see on a work order. Not when you’re running late and you still have to pee, because “irate” meant that the next job wasn’t going to be a woman in lingerie; it was going to be a guy who pulled out his penis while I fixed the settings on his television.

I know after that one, I pulled off the side of the road when I saw a horse. Only upside of Great Falls. Not too long ago, Great Falls was mostly small farms and large estates. The McMansions outnumber the farms now. But there are still a few holdouts. I called the horse over to the fence, and he nuzzled my hair. I fed him my apple. Talking to a horse helps when you can’t remember how to breathe.

Maybe that “irate” was an “irate fn ch72 out.” Fox News. Those we dreaded. It was worse when the comment was followed by “repeat call.” Repeat meant someone had been there before. If it was someone I could call and ask, he’d tell me: “Be careful. Asshole kept calling me ‘boy.’ Rather he just up and call me a [that word]. Yeah, of course I told them. Forwarding you the emails right now. Hang on, I have to merge. Anyway, it’s his TV. Dumbass put a plasma above his fireplace. Charge the piece of shit ’cause I warned him. Have fun.”

I’d walk in prepared for anything. There was sobbing, man or woman, didn’t matter. There were the verbal assaults. There were physical threats. To say they were just threats undermines what it feels like to be in someone else’s home, not knowing the territory, where that hallway leads, what’s behind that door, if they have a gun, if they’ll back you into a wall and scream at you. If they’ll stop there. If they’ll call in a complaint no matter what you do. Sure, we were allowed to leave if we felt threatened. We just weren’t always sure we could. In any case, even if we canceled, someone else would always be sent to the same house later. “Irate. Repeat call.” And we’d lose the points we needed to make our numbers.

The points: Every job’s assigned a number of points — 10 points for a “my cable’s out” call, four points to disconnect a line, 12 to install internet. We needed about 120 points a day to make our monthly quota.

A cut cable line was worth 10 points, whether we tried to fix it or not. We could try to splice it if we found the cut. Or we could maybe run a temp line. But you can’t run one across a neighbor’s lawn or across a sidewalk or street. That’s what happened with the guy who was adding a swimming pool. The diggers had cut his line. I knew before I walked in. But he still wanted me to come stare at the blank cable box while we talked. I did because the Fox News cult loves to call in complaints about their rude techs.

She blinked back the flood of tears she’d been holding since God knows when. She said, “It’s just, when he has Fox, he has Obama to hate. If he doesn’t have that …”

The tap, where the cable line connects, was in a neighboring yard. There was a dog door on the back patio of that yard. I like dogs, but I’m not an idiot. I told him it would be a week, 7 to 10 days to get a new line. He said through his teeth he needed an exact day. I gave him my supervisor’s number. This whole time, his wife was in the kitchen wiping a clean counter.

I was filling out the work orders and emailing my supervisor to give him a heads-up on a possible call from a member of every cable tech’s favorite rage cult, when his wife knocked on my van window. She stepped back and called me “ma’am.” Which was nice. Her husband with the tucked-in polo shirt had asked my name and I told him Lauren. He heard Lawrence because it fit what he saw and asked if he could call me Larry. Guys like that use your name as a weapon. “Larry, explain to me why I had to sit around here from 1 to 3 waiting on you and you show up at 3:17. Does that seem like good customer service to you, Larry? And now you’re telling 7 to 10 days? Larry, I’m getting really tired of hearing this shit.” Guys like that, it was safer to just let them think I was a man.

She said she was sorry about him. I said, “It’s fine.” I said there really wasn’t anything I could do. She blinked back the flood of tears she’d been holding since God knows when. She said, “It’s just, when he has Fox, he has Obama to hate. If he doesn’t have that …” She kept looking over her shoulder. She was terrified of him. “I’m sorry,” she said. “I just need him to have Fox.” I got out of my van.

The neighbor with the possible attack dogs wasn’t home. The next-door neighbor wasn’t either. But I looked up his account. I got lucky. He didn’t have TV service. I pulled up his modem on my laptop, perfect signal. There was an attenuator where the cable connected to his house-wiring to tamp down the signal — too much is also a problem. I got enough running a line from the neighbor’s house to theirs so the asshole would be able to get his rage fix from Hannity. I remember leaving a note on the neighbor’s door, some ambiguous lie about their internet service being urgent. I figured the neighbor might be more understanding about internet service than Fox. I sure as fuck was.

Maybe the next job was unremarkable in every way. I liked those jobs. Nothing to remember but maybe a cute dog. Maybe a few spiders. But I’d gotten used to spiders. I don’t feel mosquito bites anymore either. If the customer worked any sort of manual job, they’d offer me water. I wouldn’t usually accept. But it was a nice gesture.

Blue-collar customers were always my favorite. They don’t treat you like a servant. They don’t tell you, “We like the help to use the side door.” They don’t assume you’re an idiot just because you wear a name tag to work and your hands are calloused. The books on their shelves aren’t bound in leather. But the spines are cracked. Most of them, when you turn on the TV, it’s not set to Fox. They’re the only customers who tip.

Maybe the next job I had to climb into an attic. Maybe it was above 90 outside and 160 up there. I’d sweat out half my body weight, and my skin would itch like hives from the insulation the rest of the day. At some point, I’d blow something black out of my nose. You have to work fast in an attic. You don’t come down, not all of these customers would even bother to see if you’re at medium rare yet. If the customer had a shred of humanity, you could ask to reschedule for the morning.

Humanity is rarer than I imagined when I first took the job. One woman wanted me to shimmy down into a crawl space that held 3 feet of water and about a foot to spare under her floorboards. A snake swam past the opening. She said it wasn’t a copperhead. Like I fucking cared.

We had a blizzard one year — a few, really. Snowmaggedon and Snowverkill and Snowmygod, I think WTOP named them. We had to work. I went to one call where the problem was dead batteries on a remote. They didn’t think batteries were their responsibility. The next, they wanted me to replace a downed line. Yes, that’s the power line in the tree, too. Well, sure the telephone pole’s lying in the street, but we figured you could do something. I didn’t explain why I didn’t get out of my van. I took a picture and sent it to my supervisor with “Bullshit.”

Most of the streets were blocked. Thirty-five inches is a lot of snow. A state trooper told me to get the fuck off the road. My supervisor said, “We can’t. We do phone so we’re considered emergency service.” I didn’t have any phone jobs. No one else I talked to did either.

The supervisors made a good show of pretending to care that we made it to jobs. The dispatchers canceled everything they could. The techs, we didn’t talk much. Every so often someone would mic their Nextel to scream: “This is bullshit! They’re going to get us fucking killed!” And someone else would say, “They don’t care, man. They won’t have to pay anyway. They’ll piss test your corpse and say you were high. Motherfuckers.”

“They’ll fucking care when I plow my van through the front of their building.”

“Dude, I’m gonna ram the next little Ford Ranger I see.” Supervisors drove Rangers.

“Fuck that. I’m ramming a cop.”

“Bitch, how you gonna know what you’re ramming? Can’t fucking see the snowplow in front of me.”

I couldn’t respond. My voice would stand out. We had to hope for the humanity of others, the customers, because corporate didn’t care. They didn’t have to drive through a blizzard. The blizzards, I remember.

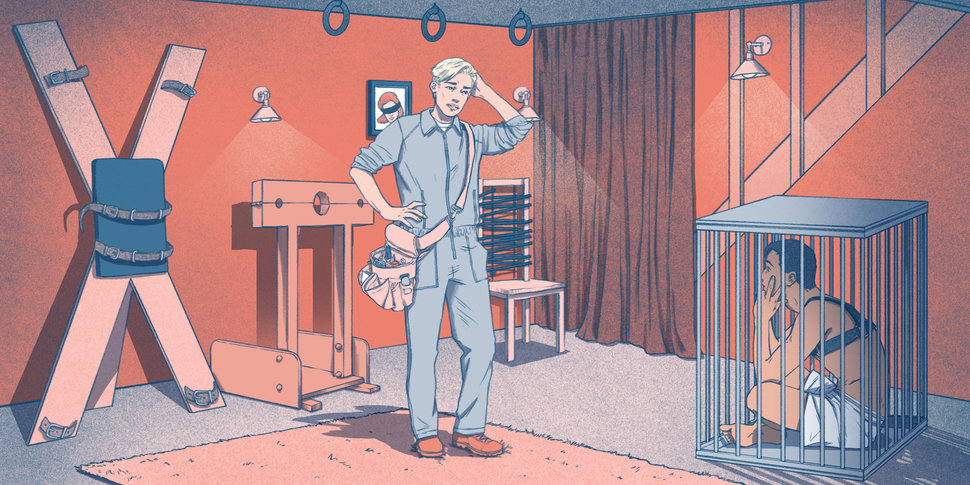

The other days, they all blended together. Let’s go back to imaginary day. Maybe next I had the woman with the bull mastiff named Otto. I don’t remember much about her because I like bull mastiffs with their giant stupid heads. I told her I needed to get to her basement. She said, “Do you really? It’s just it’s a mess.” (That’s never why.) I explained the signal behind her television was crap. The signal outside her house was great. With only one line going through the cinderblock wall, there was probably a splitter. She was taller than I am. That’s something I remember because, like I said, I’m tall. And probably a useful trait for her considering what I found next. I told her what I told everyone who balked about their privacy being invaded: “Unless you have a kid in a cage, I don’t fucking care.” Kids in cages were an unimaginable horror then. A good place to draw a line.

This is a good time to say, if you’re planning on growing massive quantities of marijuana, look, I respect it. But don’t use a $3 splitter from CVS when you run your own cable line. Sooner or later, you’ll have a cable tech in your basement. And you’ll feel the need to give them a freezer bag full of pot to relieve your paranoia. Which is appreciated, don’t get me wrong. Stoners, I adore you. I mean it. You never yell. I can ask to use your bathroom because you’re stoned. You never call in complaints. But maybe behind the television isn’t the most effective place to hide your bong when the cable guy’s coming over.

Anyway, Otto’s mom laughed and said, “Not a kid.” It took me a second. She went down to get his permission. And I was allowed down into a dungeon where she had a man in a cage. I don’t remember if she had a bad splitter. So that was probably early on. After a few years, not even a dungeon was interesting. Sex workers tip, though.

Maybe my next job was a short little fucker who walked like a little teapot and who beat his kids. Sometimes you can tell. Some of us recognize the look in their eyes, the bite of fear in the air. He followed me into the office. And he rubbed himself against my ass when I leaned over to unplug the modem. I let it happen that time. Sometimes you know which guys you can’t fight back against.

There were a lot of those. Those I never forgot. They seep into your skin like cat piss. But you can’t shower them off. It’s part of why I didn’t mind most people assuming I was a man. Each time I had to calculate the odds of something worse against the odds of getting back to my van.

One of those creeps, his suit cost more than my car. I can’t fathom what his smile cost. He had an elevator in his three-story McMansion. Maybe he thought he owned me, too. I broke his nose with my linesman’s pliers. Nice heft to those linesman’s pliers. He’d called me a dyke. I hope I ruined his suit. I lost the points.

I made it back to my van. My van became my home, my office, my dining room. I was safe in my van. In my van, I could pull off near a park for a few minutes, smoke a cigarette, read the news, check Facebook, breathe until I stopped shaking, until I stopped crying. That’s only if there was someplace to pull over, preferably in the shade. We were monitored by GPS. But if I stayed close enough to the route, I could always claim traffic. This was Northern Virginia. There was always traffic.

Maybe that’s why I was running late to the next job, and my dispatcher, my supervisor, another dispatcher and the dispatch supervisor called to ask my ETA. No, that job canceled.

Irate doesn’t always mean irate. Sometimes it just means he’s had three techs out to fix his internet and not one has listened to him. They said it was fixed. He was bidding last night on a train. It was a special piece. He’d seen only one on eBay in five years. One. He showed me his collection. His garage was the size of my high school gym. But his sensible Toyota commuter box was parked out front. His garage was for the trains. He had the Old West to the west. And Switzerland to the east. But the train he wanted went to someone in Ohio because his internet went out again and he lost the auction. He wasn’t irate. He was heartbroken, and no one would listen.

I remember he started clicking a dog-training clicker when I said the signal was good behind the modem. He said he was sorry. The clicker helped when he was feeling overwhelmed. I said I should probably try it. My dentist didn’t like the way I clenched my teeth. He said, “They all come here and say it’s OK, but it goes out again.”

This was probably around the time my supervisor realized I was pretty good at fixing the jobs the guys couldn’t, or wouldn’t. And really good with the customers who’d had enough. The guys looked at cable as a science. Name a channel, they’d tell you the frequency. They could tell you the attenuation per 100 feet of any brand of cable. The customers were just idiots who didn’t know bitrate errors from packet loss. I looked at cable like plumbing, or something like that. I like fixing things. Some customers were idiots. Most just wanted things to work the way they were promised. This guy’s plumbing had a leak. I didn’t pay attention in class when they explained why interference could be worse at night, or I forgot it soon after the test. I knew it was, though. So when he said the problem only happened at night, I started looking for a leak. One bad fitting outside. Three guys missed it because they didn’t want to listen to him. Because he was different. Because he was a customer. And customers are all idiots.

I remember training a guy around the time I was six years in. He’d been hired at $5 more an hour than I was making, 31 percent more. I asked around. We weren’t allowed to discuss pay. But we weren’t allowed to smoke pot and most of us did. We weren’t allowed to work on opiates either. We were all working hurt. I can’t handle opiates. But if I’d wanted them, there were plenty of guys stealing them from customer’s bathrooms. I could’ve bought what I needed after any team meeting.

That’s the thing they don’t tell you about opiate addiction. People are in pain because unless you went to college, the only way you’ll earn a decent living is by breaking your body or risking your life — plumbers, electricians, steamfitters, welders, mechanics, cable guys, linemen, fishermen, garbagemen, the options are endless.

Ivan came back and opened his paw to show me a gram bag of coke. He’d helpfully brought a caviar spoon. He said, “You must taste.”

They’re all considered jobs for men because they require a certain amount of strength. The bigger the risk, the bigger the paycheck. But you don’t get to take it easy when your back hurts from carrying a 90-pound ladder that becomes a sail in the wind. You don’t get to sit at a desk when your knees or ankles start to give out after crawling through attics, under desks, through crawl spaces. When your elbow still hurts from the time you disconnected a cable line and your body became the neutral line on the electrical feeder and 220 volts ran through your body to the ground. When your hands become useless claws 30 feet in the air on a telephone pole and you leave your skin frozen to the metal tap. So you take a couple pills to get through the day, the week, the year. If painkillers show up on your drug test, you have that prescription from the last time you fell off a roof. Because that’s the other thing about these jobs, they all require drug tests when you get hurt. Smoke pot one night, whether for fun or because you hurt too much to sleep, the company doesn’t have to pay for your injury when your van slides down an icy off-ramp three weeks later. I chose pot to numb my head and body every night. But it was the bigger risk.

I probably should’ve stolen pills. It would have made up for the fact I was making less than every tech I asked. They don’t like you talking about your pay for a reason. Some had been there longer. Most hadn’t. I was the only female tech because really, why the fuck was I even doing that job? Because I didn’t go to college. I joined the Air Force. They kicked me out for being gay. I’d since worked at a gay bar, Home Depot, Starbucks, Lowe’s, 7-Eleven, a livery service, construction, a dog groomer and probably 10 more shitty jobs along the way. Until I was offered a few dollars more, just enough to pay rent, as a cable guy.

My supervisor hadn’t known, said he didn’t know our pay. But he said he’d take care of it, and he did. He said the problem was my numbers were always lower than most of the guys. All those points I mentioned. So my raises over the years had always been lower. The math didn’t quite work. But it was mostly true. My numbers were always lower. Numbers were based mostly on how many jobs we completed a day. On paper, the way we were rated, I was a terrible employee. That I was a damn good tech didn’t matter. The points were what mattered. The points, I’m realizing now, were why I spent the better part of 10 years thinking about bathrooms.

The guys could piss in apartment taprooms, any slightly wooded area, against a wall with their van doors open for cover, in Gatorade bottles they collected in their vans. I didn’t have those options. And most customers, I wouldn’t ask. If I had to pee, I had to drive to a 7-Eleven or McDonald’s or grocery store, not all of which have public bathrooms. I knew every clean bathroom in the county. I knew the bathrooms with a single stall because the way I look, public bathrooms aren’t always safe for me either. But they don’t plant a 7-Eleven between the McMansions of Great Falls. One bathroom break and I was already behind.

The guys could call for help on a job. No problem. If I called, some of them wouldn’t answer. Some I’d asked before and taken shit for not being able to do something they couldn’t have done either. One of them told me my pussy smelled amazing while he held a ladder for me. One never stopped asking if I’d ever tried dick. Said I needed his. And for the most part, I liked to tell myself I could handle their taunts and harassment. But I wasn’t calling them for help. Sometimes I’d have to reschedule the job because there was no one around I could ask for help. Rescheduling meant I’d lose even more points that day.

So my numbers were lower than the men’s. I never had a shot at being a good employee really, not by their measure. Well, there was one way.

I worked with an older guy, a veteran like me. I usually got along with the veterans. He was no exception. Once, after I explained why I called him for help, he told me that he understood. He said he found vets were less likely to treat him like shit for being black. Higher odds they’d worked with a black guy before. That made sense. But when I asked him how he kept his points up, seeing as how he worked slower than the other guys, he said he clocked out at 7 every day. Worked the last job for free. It brought up his average. I wasn’t willing to work for free.

One year, though, the company tried a little experiment: Choose a couple of people from each team, let them take the problem calls, those jobs a couple of techs had failed to fix, and give them the time to actually fix the problem.

Time was the important thing. Time is why I can’t tell you what day or week or year a thing happened. Because for the 10 years I was a cable tech, there was no time. I rushed from one job to the next, sometimes typing on the laptop, usually on the phone with a dispatcher, supervisor, customer or another tech. Have to pee, run behind, try to rush the next so the customer doesn’t call and complain you’re late, dispatch gives the call to another tech, lose the points. The first few years, I was reading a map book to find the house. Then crawling down the street, counting up for 70012 because I needed house number 70028 but no one else on the street thought it important to put numbers on their house. They’d tell me I needed to pick up my numbers. One more bad month and I was out of a job. Maybe you can understand why I avoided canceling anything but the most dangerous jobs.

After a few years, I spent most of my days off recovering. I’d get home and couldn’t read a page in a book and remember what I’d read. I was depressed. But I didn’t know it. I was too tired to consider why I couldn’t sleep, why I stopped eating, why I was so ashamed of what my life had become.

Sometimes at night, when I couldn’t sleep, I’d think of the next 10 years doing the same fucking thing every day until my knees or ankles no longer worked or my back gave out. I thought maybe the best thing that could happen was that if I got injured seriously enough, but not so seriously I’d forget the synthetic urine I kept in my lunch cooler, I could maybe try to survive on workers’ comp. Most mornings, I woke and it took a minute to decide. Do I want to die today? I guess I can take one more day. If I just make it to my day off. I tried to go to school for a while. But I was too tired to learn coding. And anyway, I missed most of the classes because I’d have to work late.

That one year, though, being a cable tech wasn’t all that bad. I’d start in the morning with a couple of jobs. And the rest of day, they’d throw me one problem job at a time. And I had all the time in the world to fix them. It’s how I became the Cheneys’ tech.

My supervisor called and said, “Look at the work order I just dropped you. You’re gonna thank me.” I recognized the name: Mary Cheney, the former vice president’s daughter. I didn’t know why he thought I’d thank him. I called him back. “What the fuck are you doing to me here?”

“I thought you’d be happy. They’re lesbians.”

“Dude. They’re married.” He didn’t say anything. I said, “Google her and tell me you still think you’re doing me a favor.”

He said I was just pissed because they were Republicans. I said I was pissed because Dick was a fucking war criminal. He called me a communist. Said a couple of guys had been out. Internet problem. Read the notes. I didn’t actually have a choice. But with the pressure off to complete 12 jobs a day, I found I could actually have fun at work, joke with my boss about whether or not the Cheneys constituted a favor just because, hey, we’re all lesbians.

Mary Cheney wasn’t home. Which was good. The further I was from Dick, the more likely I was to keep my mouth shut. Her wife was friendly and talkative in the way old people are friendly and talkative because they haven’t had a visitor since Christmas. The house had a few problems. I’d fix one. She’d call my supervisor and I’d have to go back to fix another. But I finally got it fixed.

A few months later, my boss called and started with, “Don’t kill me.” He was sending me to Dick Cheney’s. Dick was home.

He had an assistant or secretary or maybe security who followed me around while I checked connections and signal levels. I’d already found a system problem outside. I just wanted to make sure I never had to fucking set foot in that house again. Dick walked into the office while I was working. He was reading from a stack of papers and ignored me. I told the assistant it would probably be a week or so. I’d put the orders in. He had my supervisor’s number.

He said something to the effect of, “You do understand this is the former vice president.”

I panicked and said the first thing that came to mind: “Yeah, well, waterboard me if it makes him feel better. It’ll still take a week.” And I walked out.

It was my last call that day. I drove the entire way home thinking of a hundred better things I could’ve said. Finally, I called my supervisor and told him I might’ve accidentally mentioned waterboarding. He laughed and said I’d won. He’d stop sending me to the Cheneys’. I don’t actually know if they ever complained. If they did, he never mentioned it.

That was the year I met a Russian mobster whose name was actually Ivan, a fact that on its own made me laugh. There were rumors of mob houses. The guys said they’d been to others. My original trainer pointed one out in Fairfax and said, if you have to go in there, just don’t try to see shit you don’t want to. I pressed him for details. But he wouldn’t tell me. I thought he was full of shit.

The Russian mob house was off Waples Mill Road. It was a massive McMansion, looked like a swollen Olive Garden. I parked behind a row of Hummers.

Ivan was a big kid with cauliflower ears. He met me at the door. Told me, “Please follow.” I followed him to an office. Same collection of leather-bound books on the shelf in most McMansions. I think they come with the place. The modem was in the little network closet. The signal looked like they had a bad splitter somewhere. (Remember what I said about cheap splitters?) I told Ivan I thought there was a bad splitter somewhere. I needed to check the basement. He said, “Is not possible.”

I said, “I can’t fix it then.” He didn’t say anything, and I wasn’t clear on where we were with the language barrier. So I added, “No basement, no internet.”

He seemed worried. Kept looking at the door. Looking at me. Like a puppy trying to figure out where to pee, a large, heavily tattooed puppy. I said, “Look, unless you’ve got a kid in a cage, I don’t fucking care.”

He nodded and said, “You stay. I ask for you.” I told him I’d stay. I heard him down the hall. Heard Russian, garbled words. A couple of doors opened and closed.

Ivan came back and opened his paw to show me a gram bag of coke. He’d helpfully brought a caviar spoon. He said, “You must taste.” I actually laughed. He seemed sad that I was laughing. I told him: “Look, I can’t. I’m at work. I’ll take it home, though, for tonight.” This was one of my first jobs that day. I did not want to find out what climbing a telephone pole felt like on cocaine.

He said, “No. You must taste.” This time he emphasized the word “must.” I told him I get sinus infections. (This is true and extremely annoying.) He didn’t understand. I pantomimed and explained a sinus infection in words like “nose, coke, bad, no breathing.” This made him happy. It was a problem he could fix. “Stay.” I was the puppy now.

He came back with a little round mirror and a little pile of coke. He said, “This is better. No cuts.” I was just standing there. I really couldn’t figure out what to do. I hoped this was some weird mob thing like when every Russian I’d ever met forces you to do vodka shots and then you’re friends. But I’m not great with vodka. And I’m really not great with coke. Drugs affect me.

He stepped closer and he looked older and very sad. He said, “I am trying to say, is safe for you if you taste. You do not taste, is maybe not safe for you now.” I figured it was probably his job to kill me and he honestly felt awful about it. I took a bump.

He was visibly relieved. He smiled all goofy and lopsided and said, “OK. Yes. This is smart decision you make.” And he took me to the basement.

I think my heart attack started on the stairs. It was good, though. Best heart attack I’d ever had. I could hear it. I didn’t know my eyes could open that wide. Which didn’t help me see.

They had a bunch of sweet gaming computers lined up on a table. But with no internet, all the guys were hanging out on a couple of sofas watching soccer. The World Cup was on. One of the guys pointed at me and asked Ivan something. Ivan said, “Yes, of course.” I understood that much Russian. And the guy gave me a thumbs up, said, “Good shit, yes?” I agreed that it was good shit. And I changed their splitter and got the fuck out of there.

We got a new regional manager after that. He called me “young lady.” I told him not to. My old vet buddy said he’d called me an entitled dyke after I left the room. The company was bleeding money with the whole “no one fucking needs cable anymore” thing. And I was back to chasing points. Eventually, my ankle went out.

I remember my last day. There was a big meeting. I hated these. The only potential good part was that they’d play happy messages from happy customers about their cable tech. If you got one, you got a $20 gift card to Best Buy. I got lots of calls, mostly because little old ladies liked me. I programmed their remotes. They never played mine in the meetings because no one ever figured out what to do about customers thinking I was a “nice young man.” That last meeting, they gave a guy an award. For 10 years, he’d never taken a sick day, never taken a vacation day. He had four kids. I thought maybe they’d have enjoyed a vacation. But that mentality is why I was never getting promoted in that company.

I couldn’t go back after surgery. My ankle never healed right. I needed a letter from HR to continue my disability. Just a phone call. But they moved their HR team somewhere else. They never answered my emails. So I work at a gay bar. The pay is shit. But I like going to work. I don’t spend my nights worrying about where I’ll pee. And no one has called me Larry in years.

Lauren Hough was born in Berlin and raised in seven countries, and West Texas. She’s been an Air Force airman, a green-aproned barista, a bartender, a livery driver and, for a time, a cable tech. Her work has appeared in Granta, Wrath Bearing Tree and The Guardian. She lives in Austin, Texas.

[ad_2]

Source link