[ad_1]

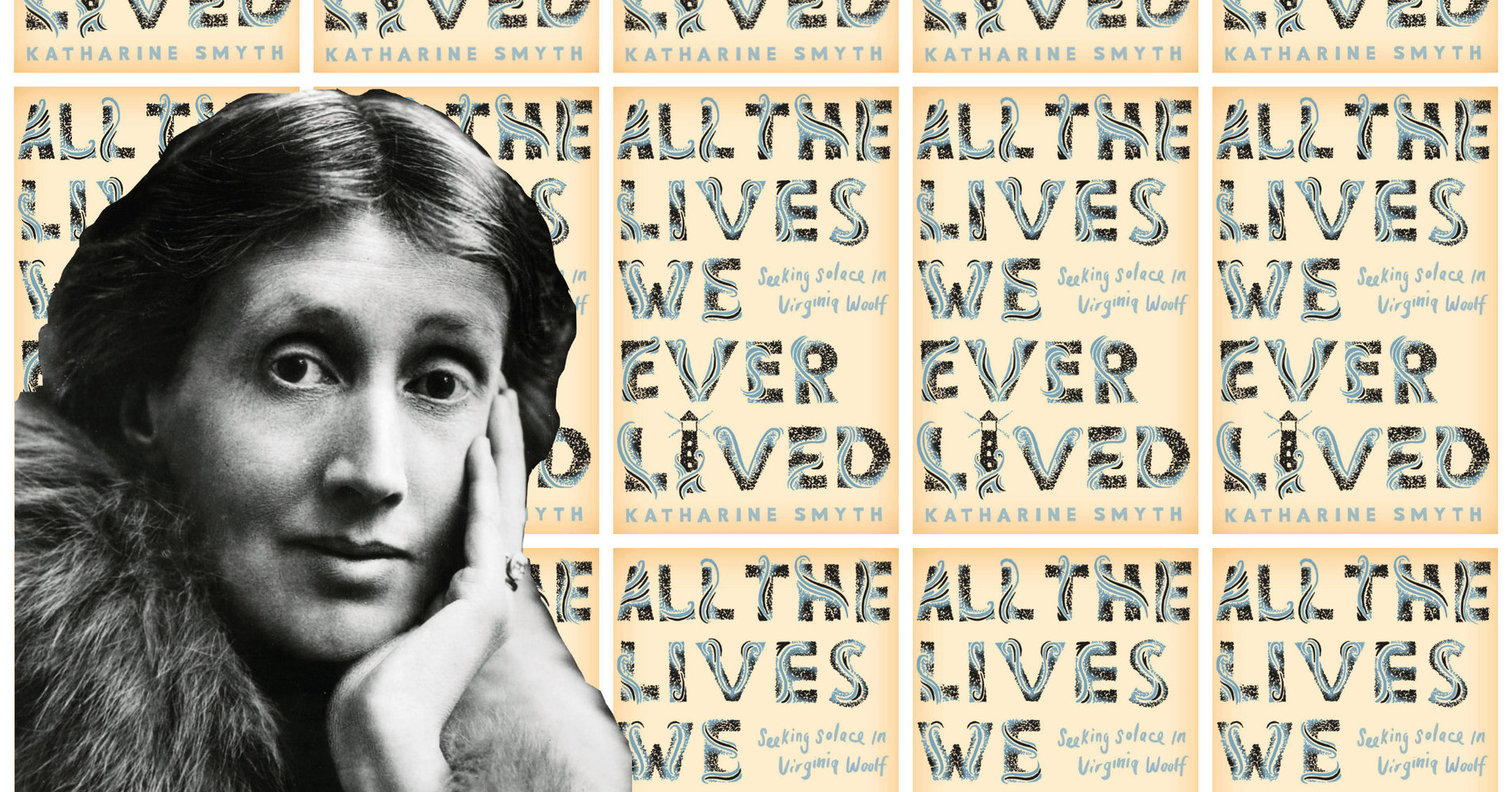

After her father’s death from cancer, Katharine Smyth found herself waiting to be stricken with an unendurable wave of pain, to be physically and emotionally flattened by sorrow. Instead, she writes in her new literary memoir All the Lives We Ever Lived: Seeking Solace in Virginia Woolf, life continued, a bit sadder and emptier than before.

Immediately after hearing of his death while in between classes for her MFA in creative nonfiction at Columbia University, “feeling melodramatic, feeling floaty,” she got in a cab to join her mother at home in Boston. On the train, she writes, “I was fascinated by the scarcity of any emotion; was I in shock?”

“I think there’s this knee-jerk contemporary reaction to grief, that it’s just going to automatically affect us,” Smyth told me during a conversation in a Brooklyn coffee shop last month. “That we’re all going to just be necessarily traumatized, necessarily going to react in some grand, dramatic way.” In her memoir, she describes once seeing a woman collapse on the street after taking a phone call that clearly delivered gut-wrenching news. Her father’s death, she had thought, would be such a moment for her, and she was frustrated and impatient with her continued ability to function.

But in her favorite author, Virginia Woolf, she saw another vision of grief that rang truer to her: that we might not fall to the ground in a paroxysm of agony upon hearing the news, that we might not sob or take to our beds. In reading Woolf, she took refuge in an account of grief that felt culturally foreign but emotionally familiar; in Woolf’s writing, death is shocking but rarely dramatic, and mourning doesn’t follow an acceptably linear arc.

“It almost felt like she was like patting me on the shoulder and being like, ‘It’s OK,’” said Smyth.

Woolf’s youth was shaped by unpredictable loss ― her adored mother, Julia Stephen, died when Woolf was 13, followed by two beloved siblings and her father in the ensuing decade. In her writing, she grapples endlessly with the ruthlessness of death and the psychology of grief, and in no book more so than To the Lighthouse, a love letter to and elegy for her mother that became the primary lens for Smyth’s memoir.

Woolf spelunks through the interiority of grief and how it clashes with the outside world, capturing every painful quirk and moment of disappointing boredom that lies beneath the somber mask of mourning. Perhaps that’s why, almost 100 years on, Woolf’s work on grief reads as quite modern, as relatable as the day it was written.

It almost felt like she was like patting me on the shoulder and being like, ‘It’s OK.’

In more than one way, All the Lives We Ever Lived is not the book Smyth set out to write. “I was originally not at all interested in writing about family,” she told me. But during her father’s final decline, she found that her writing began to turn irresistibly toward the personal ― toward, specifically, the insoluble mystery of her father’s death and her own grief.

“I worked on a manuscript for five years, maybe, that was more of a kind of traditional memoir,” Smyth said. But the book needed a hook, something to distinguish it among other grief memoirs. So she turned to one of the only things she knew as deeply as her own family: To the Lighthouse.

Smyth wrote her Oxford thesis on Woolf, but in the years since, even during her father’s illness and death, she hadn’t been thinking much of the author. “I had kind of, actually, intentionally pulled away from Woolf a little,” she said. “When I was first starting to write my own stuff, I felt like she was almost like a debilitating influence.”

But when she finally put her story and Woolf’s next to each other, something clicked. The narratives, even on a superficial level, mirror each other. Woolf adored her mother, who was beautiful and social; she sought to recreate that in To the Lighthouse’s Mrs. Ramsay, who “bore about with her, she could not help knowing it, the torch of her beauty.” Smyth’s father was her favorite parent, witty and fun and wildly charismatic. He was also an alcoholic with volatile moods who could turn cheery family dinners into teeth-grindingly tense affairs with the furrow of a brow.

The affinity between Smyth and her subject is profound even on the sentence level. She writes in Woolfian rhythms. Her sentences cascade and linger over transcendent images; she nests tangential observations into parentheses to hint at the simultaneity of experience. She insists it isn’t intentional, but rather an underlying similarity in sensibility that drew her to the modernist writer to begin with. “Meeting her as a writer felt like such a homecoming,” said Smyth, who first read To the Lighthouse in college.

Smyth’s book immediately caught my eye, because I had written before ― much more briefly ― about the comfort I found in Woolf’s writing on grief, which seemed to so closely mirror my own reaction to my mother’s death when I was 11 years old. Reading All the Lives We Ever Lived, the divergences between Smyth’s experience and my own took me by surprise.

She was in her 20s when her father died after years of treatments for cancer, while I had been a preteen and my mother’s death quite sudden. She was struck by her guilt at a perceived underreaction to her father’s death, while I recalled having been swamped by my own misery and then profoundly affected by it for years. And yet both of us saw ourselves almost perfectly reflected in Woolf’s and her characters’ losses.

Grief can be an intensely lonely experience, especially in the months after the initial bustle of attention fades away. This time “is when reading can be especially helpful,” Smyth told me. “It can make you feel seen and make you feel like you’re not alone in whatever it is you’re going through.” Perhaps this is what makes Woolf, for many readers, a particularly comforting companion in loss: Her attention to sorrow is intimate, interior and wrought with unsparing detail.

In her work, Woolf delineates a conception of mourning defined in opposition to the highly ritualized, showy funeral norms of her parents’ Victorian generation. Woolf, Smyth points out in All the Lives, “chafed beneath the suffocating mourning conventions espoused by Queen Victoria ― the parties ceased, the laughter ceased; for months, the family wore black from head to foot.”

Against this oppressively somber backdrop, young Virginia felt puzzled by the seeming inappropriateness of her own variable emotions. In her autobiographical essay “A Sketch of the Past,” Woolf recalls feeling a “desire to laugh” while kissing her late mother goodbye, even as her father and others nearby staggered about distraught.

She continued to turn this inadequacy of feeling over in her work, decades later; death, in her writing, tends to come suddenly and is not attended by ostentatious mourning. In To the Lighthouse, saintly wife and mother Mrs. Ramsay dies abruptly, in a parenthetical clause ― as do two of her elder children. In the final section of the book, artist Lily Briscoe berates herself for how little she feels over Mrs. Ramsay’s death, though Woolf also hints that at times she feels deep pain at the loss of her friend.

“For really, what did she feel, come back after all these years and Mrs. Ramsay dead?” ponders Lily. “Nothing, nothing ― nothing that she could express at all.” Then again, not being able to express feelings in the expected way is not the same thing as feeling nothing.

Books about grief can often become particularly cherished touchstones for those who have lost a loved one, and yet they seem the most fraught with the anxiety of failure; we need art to provide a form to our pain, but it never seems to get all the way there.

By the time Woolf wrote To the Lighthouse, death customs had changed. While life expectancy was, on the whole, shooting upward, Europe plunged into a grueling, bloody war. Hundreds of thousands of young British soldiers died in the trenches between 1914 and 1918. Just as it seemed premature death might be on the wane, England lost a generation of men in a horrifically violent conflict. In Alan Warren Friedman’s Fictional Death and the Modernist Enterprise, he notes that “[t]he war that was to be over by Christmas, and was to end all wars, metastasized like cancer and made continuing mass death a central feature of Western civilization” ― and one of the casualties of this constant spectacle of killing was that the elaborate Victorian mourning rituals came to seem unpalatable and meaningless.

Woolf wasn’t the only one to revolt against the age of black crepe frocks and funeral parades; the entire country had lost its taste for solemnities that did nothing to assuage ― or even describe ― the pain of such enormous loss.

For Smyth, who isn’t religious, the 21st-century American secular mourning conventions were almost too amorphous: a sudden flood of sympathy cards and flowers, perhaps a funeral, “and then it just all dries up.” In the book, Smyth remembers a Jewish friend inviting her for an afternoon of sitting shiva for her father and the immense comfort of having a designated space to remember her father and to process her loss. But mostly, she was alone. The rigid structures of mourning Woolf had wanted to blow up were imperfect, but Smyth hungered for a container, however flawed, to put her pain and confusion into.

“If Woolf was rebelling against the Victorian grieving conventions, it’s like, OK, fine, we do away with those, but then what are we left with?” she said.

But Woolf had left mourners after her with something, after all: her work. Woolf’s observation of loss ― the way it can happen so quickly, the way it can utterly destroy and also be forgotten ― can offer a certain consolation.

Perhaps the greatest consolation it provides is that of structure, for both creator and audience, to contain an experience that can feel overwhelmingly ineffable. Lily, a painter, spends To the Lighthouse working on a painting set at the Ramsay holiday home in the Hebrides. In the first section, she’s trying to capture the spirit of a home set alight by her friend Mrs. Ramsay; in the third section, returning to the house with the remaining Ramsays years after her friend’s death, Lily throws herself into the unfinished painting, more determined than ever to capture, through just the right line, the transcendent unity that Mrs. Ramsay created of her family and friends’ scattered parts.

“Lily’s grief is a mirror of Virginia’s own, and her painting a surrogate for the novel,” notes Smyth in her memoir. To the Lighthouse, itself, was conceived on the idea of a containing and connecting structure. Woolf drew a diagram in her notes of “two blocks joined by a corridor,” a form that would, Smyth writes, “communicate the horrific rupture that had put an end to her childhood,” as well as capturing the societal rupture of World War I.

Smyth embraced this form for her own memoir: 42 chapters divided into three sections of 19, 10 and 13 chapters. Grief, in particular, she thinks, might cry out for such a structure, like a trellis for our riotous emotional vines to clamber. “The fact that this is such a rigidly structured book,” she told me, “it’s sort of an attempt to give our grief somewhere to go, or a way of trying to shape it or trying to make sense of it, by putting it in this very strange mold.”

In All the Lives, she lingers frequently over the amorphousness of grief, the way it eludes our grasp, the way the ground constantly seems to shift beneath it and leave us stumbling.

“Death confounds language, brings to light its limitations,” she writes; “there are no words to properly convey the brain’s frustrated, confused, hopeless, determined scrambling to comprehend what it means that its favorite person has simply vanished; nor to convey its little, concomitant bursts of understanding, for it sometimes feels as if we could have all the answers if only we knew how to say them.”

Books about grief can often become particularly cherished touchstones for those who have lost a loved one, and yet they seem the most fraught with the anxiety of failure; we need art to provide a form to our pain, but it never seems to get all the way there. “I think death is just so unfathomable,” Smyth told me. “It’s still … I still just have no idea what it means for someone to be dead.”

In literature, we can find, if not the answers, a consolation, a shelter and a community, an unending conversation about mortality and loss that creates unity from the fragmentation of life and death.

[ad_2]

Source link