[ad_1]

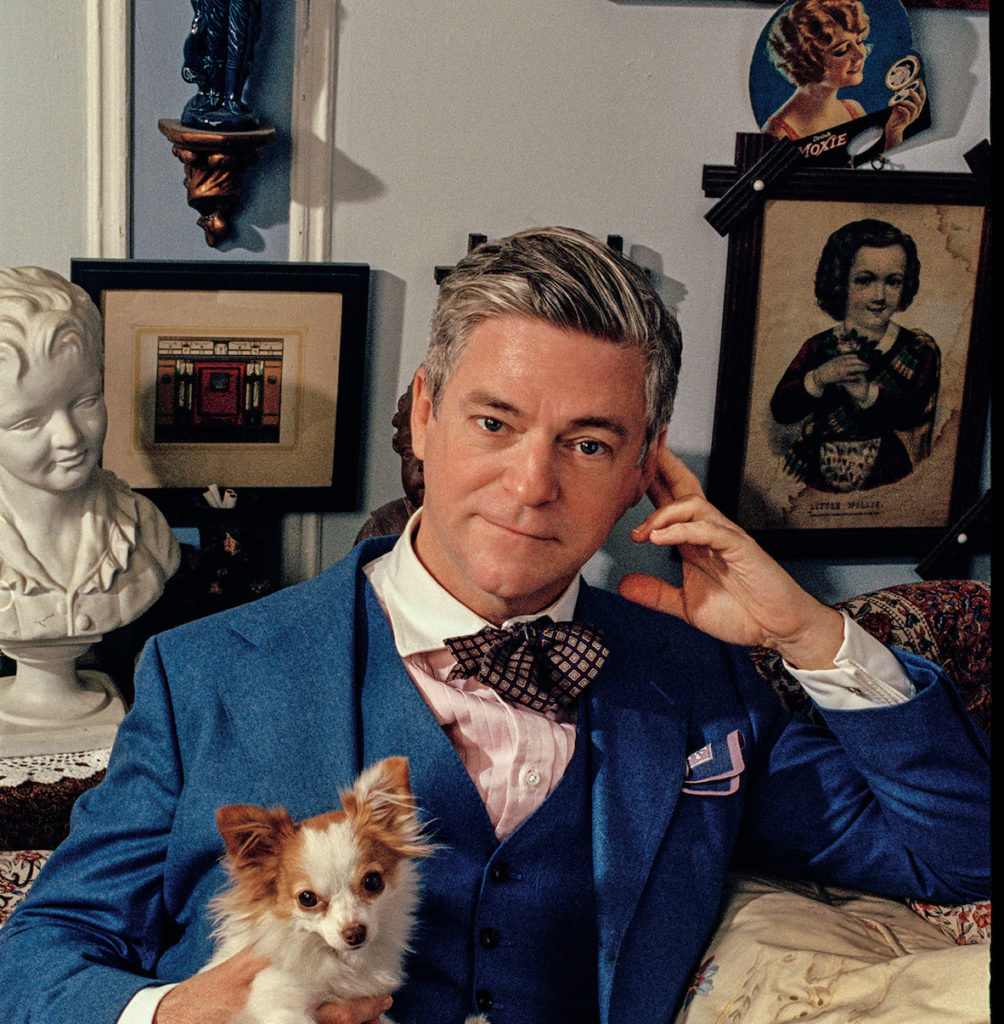

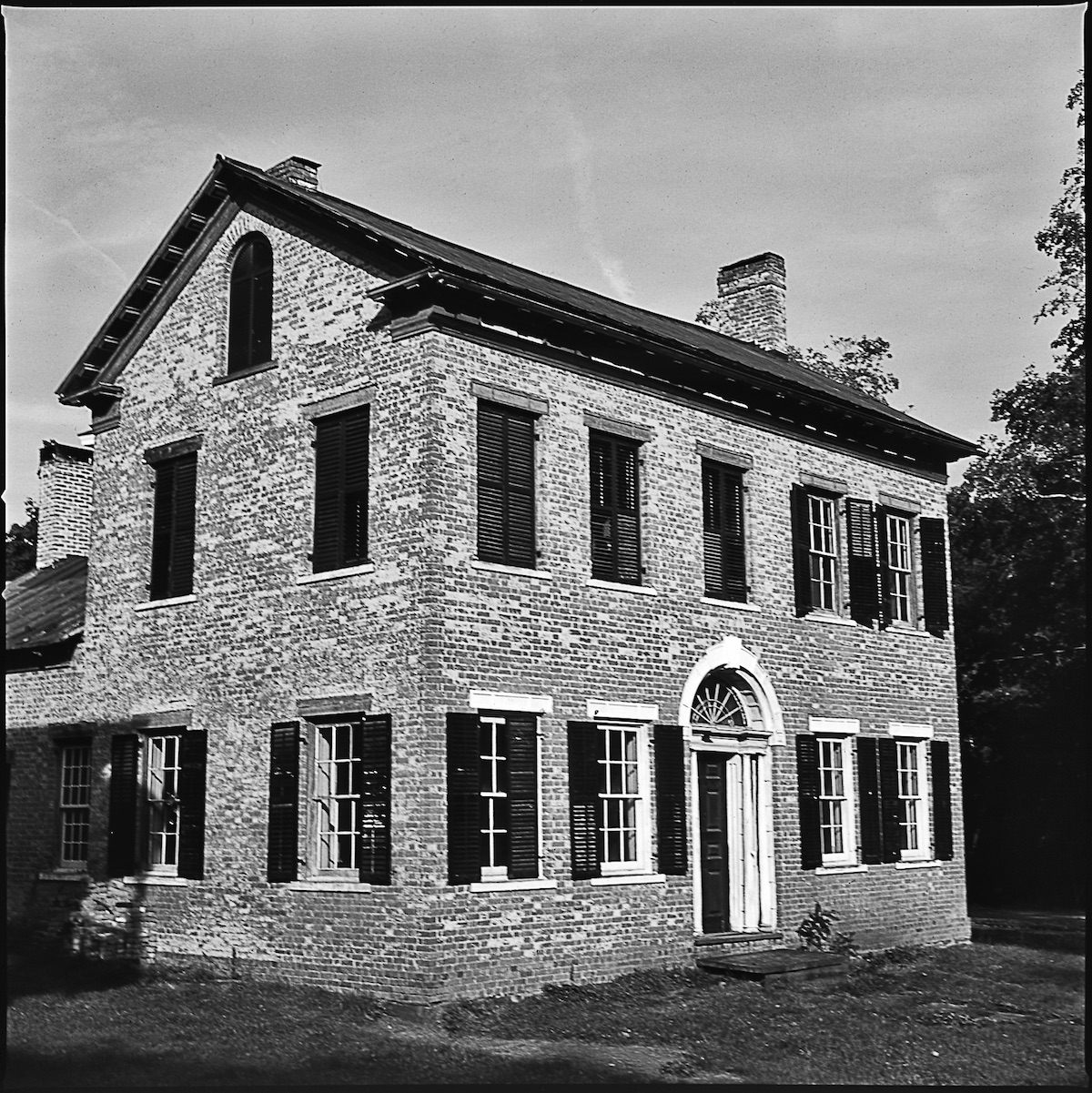

Peter McGough.

©KATE SIMON

The last time the art marked experienced a significant slowdown was in 2008, in the wake of the global financial meltdown and the fall of Lehman Brothers. But anyone older than, say, 50 will tell you it was nothing compared to the recession of the early 90s, in the wake of the late 80s stock market crash, which shuttered many a Soho gallery and ended numerous artists’ careers.

Staying financially afloat is one of the hardest things an artist can do. It’s all the more difficult when a stock market crash and the AIDS crisis is on the horizon. In his new book I’ve Seen the Future and I’m Not Going, published by Pantheon Books and releasing on September 17, artist Peter McGough—one half of the duo McDermott & McGough—discusses his time in the downtown New York scene of the 1980s, attending hip clubs and mingling with the likes of Keith Haring, Jean-Michel Basquiat, and Andy Warhol. McGough writes of spending lavishly on a house in upstate New York and hosting baroque parties—and then, when the recession hit, nearly going broke. “I know how to spend money,” McDermott once said, according to McGough, who writes that his colleague “never learned the art of saving.” An excerpt from the book follows below.

For context, and so as not to clog up McGough’s flowing diaristic style with brackets, here is a list of some of the key players:

David McDermott: Author Peter McGough’s partner in art, and in life, here referred alternatively as “McD” and “David”

Bastian: A young man the two artists become involved with, who lives with them off-and-on

Jacqueline Schnabel: Then wife of painter Julian Schnabel, who is referred to simply as “Julian”

—The Editors of ARTnews

Black Monday, October 19, 1987, was the day the stock market crashed. We didn’t have a television or radio and we hardly ever looked at newspapers, since McD liked to get his news from hearsay and gossip. I knew of the crash, but I didn’t think it would affect the art world or us. Our work was still selling well, and we had future exhibitions lined up. We had never saved a penny, however. In addition to the Model T we had bought a 1925 Model A truck that didn’t work and a pile of antiques. We had a big staff—as many as fourteen people which included a chef preparing lunches at one point. There were also three horses, handmade saddles, boots, wagons, three properties, three automobiles, fancy restaurants like the Odeon, Bar Pitti, and Il Cantinori, and parties and many bills that we didn’t pay.

Even with the vast number of photographs [art dealer] Howard [Read] sold each year we always seemed to be broke. One day we sold a hundred grand’s worth of paintings—the equivalent of $214,000 now. That was mostly gone in three days. Adding to his many possessions, McD had bought a large navy 1930 Graham-Paige automobile. It had a moss-colored mohair interior with a green silk shade in the rear window complete with a tassel. A cut-glass bud vase was screwed into the side of the door on the right. Since it was not heated, it had a blanket bar on which we kept a heavy throw, like what we used in the Model T.

One day when McD was going over the Williamsburg Bridge, he saw a rental sign on an old bank built in the 1860s French Second Empire style. McD said we should take it as our studio. I objected to yet another expense but McD was determined. The top two floors were available (a new bank had moved into the ground-floor space, which still had its original bank booths), twenty-five hundred square feet each. The toilets hadn’t been changed since 1900, and in the very top of the building was an old room with faded original wallpaper where we could see the outlines of framed images taken down long ago. We rented the two floors, used the lower one as our studio and painted the walls light blue; the top floor, with twenty-three-foot ceilings, was our photography studio, which we painted a dark orange.

Later the bank went under and we took the street floor, too. We rented all three floors for eight thousand a month. In addition, we had the rent on our apartment on Avenue C and the house upstate. Next, McD went on a spending spree to decorate the three floors of the bank building. He bought a huge conference table and chairs for the ground floor, but we already had quite a lot of furniture from various storage spaces. All our costumes and period clothes went up to the photo studio, where we made a painted backdrop for doing portraits.

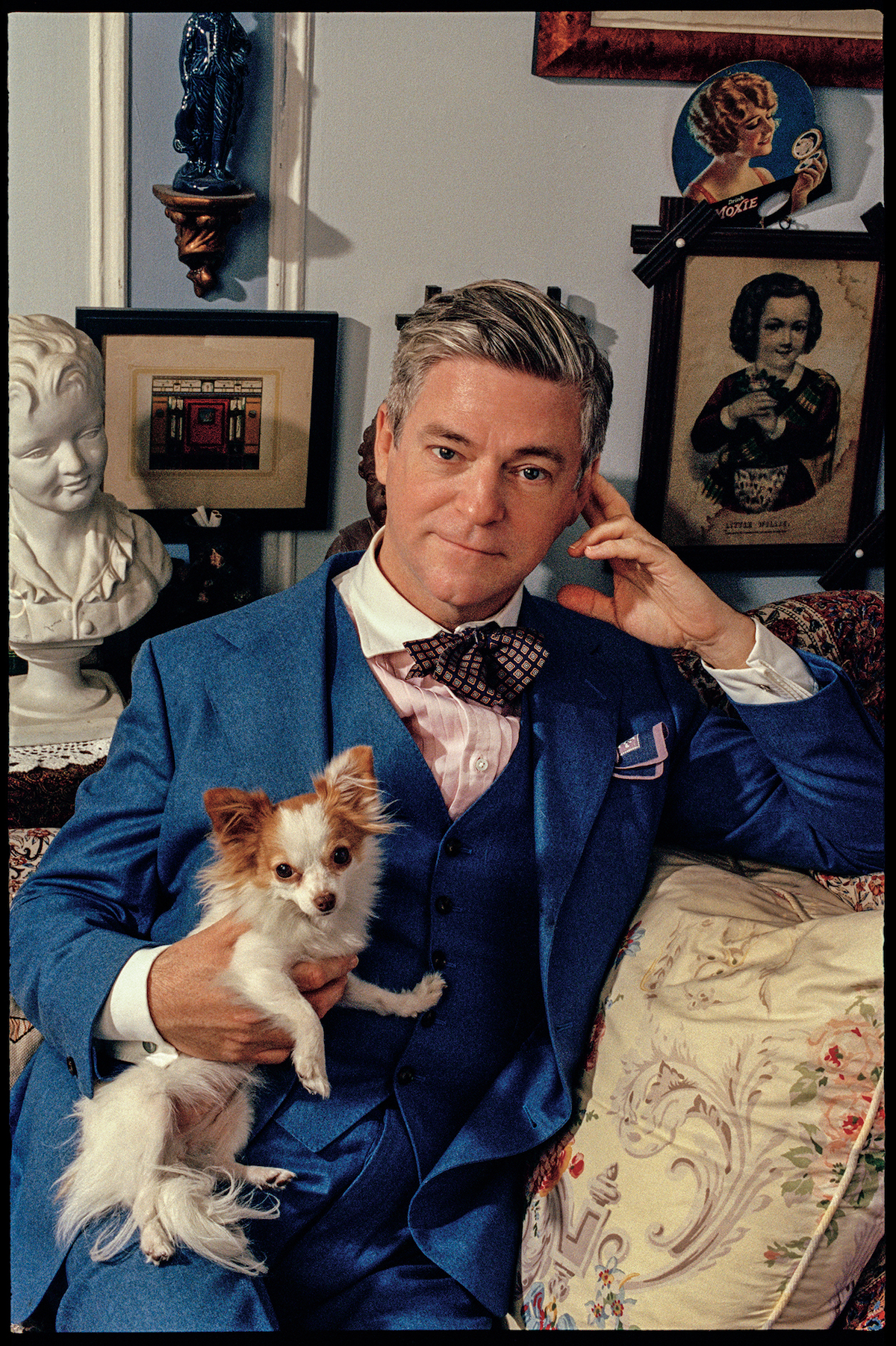

COURTESY PANTHEON BOOKS

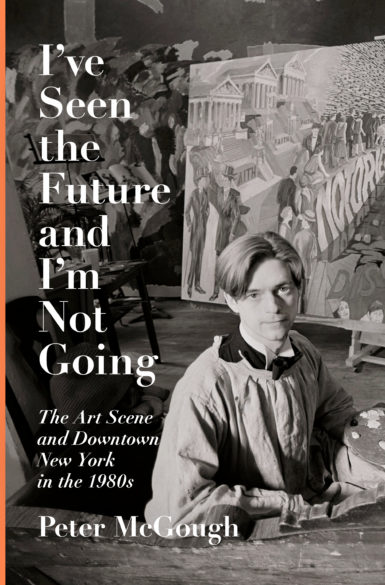

The Flemings, John Patrick and Walter, had a house up in the Catskill Mountains. They told us about a property we had to buy in Oak Hill, the next town over. We went to look at it with them, peeked into the eighteenth-century windows, and fell in love with the place.

It was a brick house from 1790 that had a working hand pump by the side of the kitchen as its only source of water, a large 1880s general store next to it, and an apartment with original wallpaper. The store that stood there was tacked onto the back with large barns behind it and a two-seater outhouse that had a wallpapered interior and a drawer that, when full, you could pull out and empty. Neither building had been modernized. Behind was a running creek.

We didn’t act fast enough and the house was sold. A few years later, however, it came on the market again in 1989 and since we had just sold a group of paintings we bought the property. We set up a balloon payment so we didn’t have to put down as much money and the former owner held the mortgage. After moving in, we began a deeper headway into the past through [our friend] Bastian’s passion for horses.

Quite a lot of money was coming in with sales of our photographs and paintings. We had never experienced anything like it. We bought Bastian two Morgan horses that he kept behind the house after building a fenced-in area for them. Then there was all the custom tack that was needed along with the hay, the grains, the blacksmith, and the vets. I used an old shed in back as a painting studio. I couldn’t use the barns because we had just bought a two-seated carriage, a surrey, and a wooden omnibus with a painted side that sat eighteen.

We made another trip to Williamsburg, Virginia, and bought a pile of copper pots, wooden buckets with rope handles, kitchen ladles, and other spoons. We also brought locks of our long hair to have eighteenth-century wigs made. We returned to the Catskills with everything we had gotten.

McD would always say, “I know how to spend money.” He had great taste in objects and furniture and could spot them with ease, but he never learned the art of saving. He bragged that he never wasted money on alcohol and drugs, “so I don’t feel guilty spending it on antiques.” He was creating his fantasy, stating, “This is my real art.” He was a natural installation artist.

Bastian bought a child’s old wooden wagon. He had harnesses made for the two hunting dogs we had bought him—a Springer and a Brittany spaniel. He hooked them up to the wagon, and we then put our two miniature dachshunds in the back.

There was a craze [in the early 20th century] called Egyptomania, dating back to the 1869 opening of the Suez Canal. So McD became inspired to have a fête of our own. His first step was to have the invitation copied from Tiffany’s original. It was on parchment paper, rolled and tied in a string, sealed with wax, and hand-delivered around town. The invitation stated: “Dress in the time of Cleopatra.”

We hired a friend who was a seven-foot-tall black man to be the guard at the door of our studio in the bank in Williamsburg and stand between two urns with fire flaming out of them. They were actually two city garbage cans with wood from the street that we doused with lighter fluid. You could do anything in that neighborhood then, just like in Alphabet City. We had a man in a white robe reading from the Koran in the echoing hallway as the visitors arrived, but we soon had to ask him to leave because he was groping the scantily clad female guests. We copied eight outfits that Michael had from the original fête for our guests who came without costume. On the second floor we had an Arab band with a belly dancer as four peacocks walked freely between ropes that made a fence around the columns.

Upstairs was an eighteen-piece orchestra that played popular dance music from the 1910s. I was dressed as the Indian goddess Lakshmi, in scraps of Indian fabrics, and McD wore a Roman helmet, shield, and leg guards from his movie Rome ’78; he kind of resembled the space-man from Bugs Bunny cartoons. Jacqueline Schnabel came dressed as Cleopatra, wearing a necklace and headdress and a flowing, silk lime-green gown. We served Middle Eastern food to guests lounging on blankets and pillows. Afterwards David and I climbed up the steps to a stagelike wooden platform with an Egyptian backdrop of the Sphinx David in a helmet from James Nares’s film Rome ’78 at the Egyptian fête we gave at our studios in the Kings County Savings Bank and the Pyramids as Jacqueline was carried through the crowd on a wheelless rickshaw by two scantily dressed musclemen to join us on the stage. We then had the party revelers form a line, and bow as they were introduced to us. And of course there was no alcohol, to the chagrin of the guests. Some ran across the street to Peter Luger’s restaurant in their costumes to load up on booze. We spent twenty thousand dollars on the evening. That night in our studio it was 1990, 1913, and 40 BC all at the same time. It was joyful evening, in the midst of a crack epidemic and AIDS. The future seemed bleak, and the party was a celebration in spite of it all.

After buying Oak Hill, David rented a magnificent early-eighteenth-century stone house on a highway an hour away. It still had a shadow of crossed swords over the mantel. The house was resplendently original, but now we had another rent and also a mortgage to pay. We had sent Bastian down south to Virginia to train with a horseman who drove carriages in a city park.

David McDermott in a helmet from Rome ’78.

COURTESY PETER MCGOUGH

In 1992, the art market was beginning to feel the effect of Black Monday, so I let many assistants go. I had to finish the whole show with the taped lines David had begun, without him. The paintings were sent to the Armory [Show]. Only one small painting sold. We had never experienced that before. [Dealers] Angela [Westwater] and Gian Enzo [Sperone of Sperone Westwater Gallery] were disappointed and sent the paintings back as soon as the Armory Show ended. This was the first sign that the market had affected us. Uptown on Fifty-Seventh Street, Howard said, “It’s a bloodbath out there.” Now we were letting even more assistants go, then our chef. I let our British secretary, Jane, who was Jacqueline’s former nanny, go. We needed money badly. I went uptown to the Miller Gallery to ask for help. Robert Miller was very cheery and walked me into his office while telling me he was part of the one percent. I had never heard that term before. As I sat down he asked, “Where are you going?” “I’m not leaving the gallery,” I replied. Amazingly—and I still can’t believe I did it—I asked if he could give us two hundred and fifty thousand dollars. It didn’t land well. I went back to the studio, to the dismay of McD.

We asked for the return of our photographs, but we owed the gallery thirty-three thousand dollars in framing costs. Julian helped us out and wrote a check. David went over to Julian’s studio and gave him triple that amount in the returned photographs.

Then Sperone Westwater dropped us. But we still owed Gian Enzo a very large sum of money, too. Then the San Francisco gallery never spoke to us again. We were box-office poison.

Somehow, during all this we had agreed to let a young German woman named Barbara, who was at NYU film school, make a documentary about us.

One day in the middle of shooting there was a knock at the side door. We were filming in our studio on the ground floor. It was three people from the IRS: two white men and a black woman in suits who ordered their way inside. “We’ve come to collect payment,” one of the men said. They sat down right in the middle of the shoot at our large boardroom table with their McDonald’s lunches and started eating while making jokes about us in a stage whisper. I told the film crew to go outside while I spoke with them. Since we didn’t have any money, they took all of our framed photographs we had just received back from the Robert Miller Gallery. They took about $250,000 market-value worth of images. We had been called to their offices a month or so before and they had told us how much trouble we were in and how they would make us pay for ignoring them.

Howard called me and said that Sotheby’s had all seventy photographs and were going to put them up at auction. Harry Lunn, who had started to represent us, called Sotheby’s and bought them all for fifteen thousand dollars. When I asked to buy them from him he said, “No, these are mine.” What could I do? He was our only dealer, and I didn’t have any money. With the bad art market, the photos were cheaper and easier to sell now than paintings. Then Oak Hill was seized and locked by the IRS with orange stickers on all the doors and windows, including the general store.

The outside of Oak Hill House.

©GROSS & DALEY

We were back to being poor again, with meager finances, but now owing so much money in back taxes and rents as well as our balloon payment of fifty thousand dollars due soon for Oak Hill.

The auction date was announced, and Barbara said she’d drive us and help out. I went around with her to different bank machines as she took out six thousand dollars. We arrived three hours late, and people were busy bidding. The cinderblock warehouse in Albany was set up with a podium for the auctioneer and our belongings on either side. We found seats in the front and started bidding. We had contracted a lawyer before who said not to worry he’d handle it. We later found out, from no returned calls, that he hadn’t: he went on vacation for a month without telling us, and then it was too late. I saw a plump, dark-haired woman in glasses and a messy ponytail with our tailor-made eighteenth-century incroyable clothing of knee britches, waistcoats, and numerous scarves made in different colored silks. We had them made for a baroque ball in Vienna that we ended up not going to. I begged to buy them back. She replied, “No way—my friends and I like to get dressed up and ride horses.” I followed her and begged her to give me my father’s First Communion picture, which she held in her hand. She let out a big, annoyed sigh and handed it back to me and turned away.

There on folding chairs sat all the dealers we knew and had supported. I went to greet them and asked them to please let me buy our things back. “Yes, yes,” they’d say, and then bid against me as I walked back to my seat. They said little to me and continued buying. McD went outside as I bid on some things. The Warhol eighteenth-century bench came up, and it went higher than I could afford. Each piece had a story and a memory for me: the nineteenth-century crystal champagne flute we bought in Naples, or a beautiful eighteenth-century wooden chair I meticulously scraped decades of paint off for weeks, making a mixture of all the different colors blending underneath in powdery shades of green and pink.… I went outside to find David. He was sitting on the parking lot macadam in his white suit with his head bowed down and his boater hat covering his face. He was sitting in the dirt against a chain-link fence matted with weeds. I was shocked to see him sitting in the muck.

“David,” I begged, “get up, you’re sitting in the dirt.”

“I just can’t believe this is all happening.” The scorching sun above had lit up the parking lot, and his white clothes were blinding me.

“I know, it’s horrible. But don’t sit there—you’re ruining your suit.”

“I don’t care. I don’t care about anything. Why should I bother—for what? It’s all gone, anyway. Everything’s ruined.”

We returned to the empty house in Oak Hill, where we slept on a mattress on the floor, using the old threadbare woolen flags as bedding. There was nothing else left except some unmarked tin cans in the little pantry. It was beyond depressing. We both stayed silent on how unhappy we felt. And then our balloon payment of fifty thousand dollars was due. We barely had fifty dollars. The owner who held the mortgage had told us earlier that he would refinance it for us, but he changed his mind. He took the property back, though we could stay there till the date of eviction.

The weeks after the auction are all a blur now. I had to pay Barbara the six thousand she loaned me, so I called a friend from Mexico and borrowed it to pay her back. I gave him some salt print photographs as remuneration.

With John Patrick’s help I sold the bank’s office furniture and some other pieces from the studio, since no one was buying art from us. The new owner of Avenue C took me to court to pay the seven months of rent I owed. I lost the case. Then he sold the building to some gays and I was given a month or two to move. Meanwhile David was in Ireland, and I’d call now and then or get a collect call from him. He’d ask for some money. I tried to send as much as I could. [Our friend] Cheryl came to him one day and asked how long he’d be staying there. He didn’t have an answer, so he knew he had to leave. They found him a “tigh,” a little open shack with broken windows and no doors in a field where cows would enter and walk among the debris of old clothes and garbage inside. It had a little stair that went up to a small bedroom and the tiniest fireplace, no bigger than a portable TV. David fixed it up and repaired the door.

I had to pack up Avenue C. And our studio—the top floor of the bank—already had three floors of our belongings, including the stage from the Egyptian fête. So not only did I have to move out of the studio but also out of the house in Manhattan. Both properties were chock full of furniture, our costumes and extensive wardrobe of antique clothing, numerous objects, large wooden cameras, all the photos and their large negatives, plus our paintings and so much more.

For the next few months it was a daily trial of packing all the effects of our life. I found a company to move all the belongings and I could pay them later. I called some neighbors up in Oak Hill who had let us store things of ours in their barn. When I called to retrieve them, they told me they wanted a five-thousand-dollar storage fee. I was so shocked that I called John Patrick for advice. “I’ll handle it,” he said. He drove up to the mountains and threatened the people that if they didn’t give back our belongings they’d have him to deal with. He succeeded in getting them returned.

I had a week left to get out of Oak Hill. My friend Paul Meleschnig drove me upstate to collect the few things I bought at the auction and our feather mattresses and flags. After we filled the car I said, “I just want to go back inside.” It was my favorite property, and I wanted to see it one last time. I went into the house and looked through the empty rooms, from the parlor with its 1900 wallpaper, up the small mahogany-railed stairway with the original pink walls to the two bedrooms and dressing rooms. Bastian had the one with a columned fireplace. My room had the original paint on the wooden closet door. I closed all the shutters in both rooms. I went back downstairs and bolted the front door and placed the large brass key on a hook. I walked through the dining room into the kitchen, where we made our meals on a hook over the fireplace as we had done at Wardle House. I went up the worn stairs to where David slept. I just looked at the room and remembered bits of our happy conversations when we had first bought the house. I closed his bedroom door, went down the stairs, and walked out through the small pantry and placed the tiny lock on the back door, hiding the key under a rock as we had done so many times.

I went through the general store in all its stained-walled darkness and looked out the shop’s windows which I used to decorate for the holidays. I went upstairs to the apartment, closed every door, and headed to the barns in the back where we had the carriages and to the paddock where the horses were kept. The homemade fence was still up. I passed the stone wall we paid fifty thousand for, to the stone steps to the creek we used to swim in. Again, I started to sob. I had spent very little time here since I was always working. Working for what, now? I walked back to the car. I took my seat next to Paul and said, “Let’s get out of here.”

I had finished packing the boxes from the two floors of Avenue C and then headed to tackle the Williamsburg studio. I rolled up our twenty-two-foot painting Opium Smokers Dream that we copied from a photo Michael Burlingham had of a painting belonging to his great-grandfather, Louis Comfort Tiffany, and put it with everything else going to Ireland. It was all taken and put in containers and shipped to the docks of Dublin. It was 1995, and with no place to live or work, I booked a flight to Dublin to live with David, who had rented a small house near Ballsbridge. We then started painting in the parlor floor, and after a while we rented a small art studio in Temple Bar in downtown Dublin on the River Liffey and were back again making art together and exhibiting. Bruno Bischofberger had many silhouette commissions for us, and through his ex-gallery director Andrea Caratsch we started showing with Jérôme de Noirmont in Paris. So, life was working on a much smaller scale, but after everything we went through I felt fine with it, even if I still missed our life and our friends in New York.

And then I didn’t feel so well.

From I’VE SEEN THE FUTURE AND I’M NOT GOING by Peter McGough. ©2019 Peter McGough. Reprinted by permission of Pantheon Books, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House.

[ad_2]

Source link