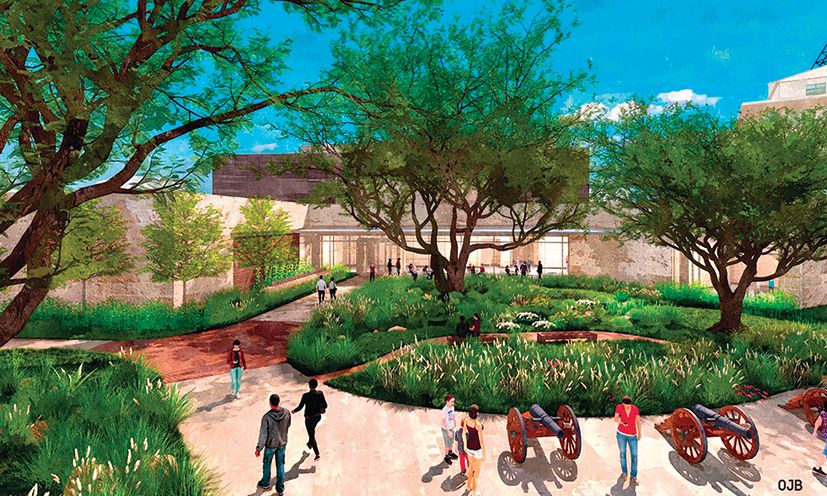

A rendering of how the planned new Alamo exhibition hall will look. The new building would sit alongside the Unesco-listed Alamo Mission fortress compound that was at the centre of the Texas Revolution battle in 1836

© Alamo Trust, Inc

After nearly a decade of deliberation, an exhibition hall designed to house the Phil Collins collection of Alamo artefacts will open in March next year in San Antonio, Texas. The British pop star is a lifelong enthusiast of the 1836 Battle of the Alamo and donated his more than 400-piece collection to the state of Texas in 2014 to support a $400m revitalisation of the historic plaza, which houses the Alamo and other Unesco-listed sites memorialised for their role in the Texas Revolution.

The $20m mini-museum—a two-storey building spanning 24,000 sq. ft and designed by the New York-based architecture firm Gensler—foreshadows an ambitious but contentious plan to build a $150m museum to showcase the full breadth of Collins’s collection. The project has been embroiled in controversy due to allegations that several pieces in the collection are inauthentic. Scrutiny has also fallen on the public funds spent on the museum, with critics arguing the funds should have been spent on local public health services rather than a tourism incentive.

Collins’s collection came to public attention after the publication in 2012 of his book The Alamo and Beyond: A Collector’s Journey, in which the Genesis frontman expands on his fascination with the 13-day siege of the Alamo Mission fortress compound.

Collins began amassing works in the early 1990s. The first piece Collins acquired was a receipt for a horse, saddle and bridle purchased by John William Smith, an Alamo courier and later Texas politician, which is dated about a month before the historic battle. The collection features a mix of objects allegedly found on the battlefield and others discovered via archaeological digs, including an excavation that Collins funded in 2007 underneath a nearby antiquities shop owned by the dealer Jim Guimarin, one of several people who have been accused of selling some questionable pieces to Collins. Guimarin has denied these allegations.

In their 2021 book Forget the Alamo: The Rise and Fall of an American Myth, the historians Chris Tomlinson, Jason Stanford and Bryan

Burrough claim that the Collins collection contains several “deceptive” pieces, including a knife once supposedly owned by the American folk hero and defender of the Alamo Jim Bowie, as well as a shot pouch owned by Davy Crockett and a knife owned by William B. Travis. The Bowie knife, the book claims, lacked provenance documentation and was reportedly authenticated by a psychic.

The knife was acquired from the historian Joseph Musso via the businessman Alexander McDuffie, who earlier this year jointly filed a

defamation lawsuit against the authors of the book, the publisher Penguin Random House and Texas Monthly magazine, which published excerpts from the book, arguing that the publications contained “false statements, mischaracterisations and significant omissions”. The as yet unresolved lawsuit argues the plaintiffs suffered blows to their businesses and reputations as a result.

The agreement made between Collins and the state of Texas in 2014 was seen as a publicity opportunity that would help raise the public and private funds required to bolster the Alamo complex. The plaza, which contains the 18th-century Alamo Mission at its centre, receives more than two million visitors each year but lacks the facilities of a premier public institution or heritage site.

Singer Phil Collins has donated his collection of Alamo artefacts to the state of Texas

Photo: Robin Jerstad/ZUMA Press, Inc./Alamy Stock Photo

The contract between Collins and the state stipulated that the larger, four-storey 100,000 sq. ft, museum should have been constructed by October last year. Collins had the option to withdraw his donation if the museum construction missed that deadline, but decided to continue with the project, despite a series of delays relating to disputes over public expenditure costs. The larger museum is now tentatively scheduled to open in 2026.

The exhibition hall opening next year will display just 50 pieces from the Collins collection. The remainder of the 10,000 sq. ft exhibition space will include Spanish colonial-era pieces donated by the philanthropists Donald and Louisa Yena, works from collections held by the Daughters of the Republic of Texas, which once administered the site, and pieces from the Alamo Trust’s own collection, which spans around 1,800 items.

The Alamo’s senior curator, Ernesto Rodriguez, declined to confirm whether the latter collections had been included to replace the pieces from the Collins collection that have provenance concerns.

“The project is more than the Collins collection; the Collins collection is just a small portion of it,” Rodriguez tells The Art Newspaper. “Rather, it’s about showing a story of how people collect. Every object has a story to tell and that’s the important thing about a museum—that we tell a story honestly, whether it’s good or bad. We are focusing on telling the honest story of a collector’s journey.”

Rodriguez argues that claims that most of the Collins collection had questionable provenance is “misinformation”.

“There were a few items [with provenance issues],” he says. “But those will help us tell a different side of the Alamo story”. All the pieces in the collection, which were charitably given to the state for free, are “important in their own right”, he says. “Ahead of the opening of the larger museum, we’re doing a lot of research on the collection as a whole”.

It is still unclear what will be shown in the museum when it finally opens. But works from the Collins collection will be displayed with labels stating which items are replicas and how they came into the musician’s possession, according to Rodriguez.

Rodriguez adds that the controversies and disputes that continue to dog both the collection and construction of the museum have overshadowed Collins’s commitment to making the story of the Battle of the Alamo accessible to a visiting public. “Unfortunately, people are focusing on a couple of items and making the entire Collins collection seem invalid,” he says. “The collection not only tells the story of the Texas Revolution but also about how people collect and the perils of collecting. He’s a wonderful individual who has been very generous to the Alamo and the people of Texas.”