[ad_1]

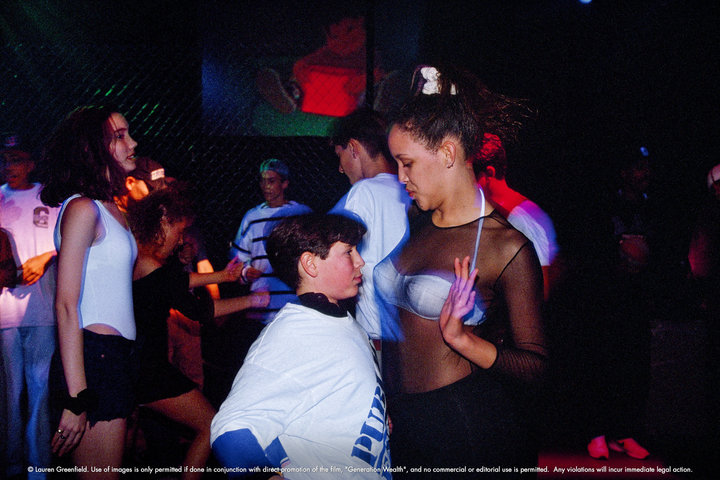

One of the most prophetic photos in Lauren Greenfield’s 25-year-long documentary project, “Generation Wealth,” shows a 12-year-old Kim Kardashian hanging out with friends at a school dance in the early 1990s.

Dressed casually in overalls and a white T-shirt, Kardashian is more than a few reality TV spinoffs away away from the glam icon she’s become. Yet her lips are touched with rouge, hinting at a budding fancy for self-enhancement. And while her classmates ignore the camera in their midst, Kardashian perks up at the sight of it, gazing into the lens with curiosity and slight amazement.

It’s an eerie premonition of what’s to come, the Kardashian-ization of our cultural consciousness. Back in the ’90s, Kim K. was another privileged kid at a Los Angeles middle school populated by celebrity offspring. But fast forward a couple decades and “[k]eeping up with the Joneses literally became keeping up with the Kardashians,” Greenfield often repeats in interviews about her project.

Greenfield, the filmmaker behind “The Queen of Versailles,” has spent two and a half decades obsessively filming, photographing and interviewing hundreds of subjects like pre-E! Kardashian, whose lives have been in some way warped by capitalism’s scourge ― from hedge fund managers to child beauty queens, aspiring rappers to trust fund teenagers.

The anthropological study took the form of a photography exhibition last year, a disorienting glimpse into the lives of the 1 percent, as well as with those who crumble in their desperate attempt to reach the upper echelons. Now, it’s headed to the big screen as a documentary distributed by Amazon.

Overall, the documentary ― like the photo project that preceded it ― critiques what it perceives to be our new, debased American dream and everything that comes along with it: greed, vanity, unchecked ambition, an obsession with surfaces. All no good, very bad consequences of corporate capitalism.

Kardashian reappears in the film, framed as the embodiment of societal ills all grown up. Clips of her sex tape play as Courtney Roskop, a former adult film actress, says, “I always say Kim is my inspiration.”

Greenfield posits Kardashian as the ultimate incarnation of our fame-hungry culture and its all-consuming desire to get more by doing less. Her reality TV empire played a critical role in obscuring the line between fiction and reality. Most damningly, Greenfield suggests, she’s transformed her body into a commodity, embraced sexuality as a form of currency, and inspired other women to do so, too.

And therein lies the problem with Greenfield’s doc.

Whereas the project’s still photos depict their subjects ― flawed and outrageous as they may be ― with empathy and detached fascination, as if her camera can’t help but be somewhat seduced by the shiny horrors it aims to criticize, the film lacks this same nuance. Instead, it beats viewers over the head with overwrought narration, a cheesy soundtrack and a moralizing tone ― one that’s particularly deaf in its treatment of women, who, in an effort to climb the ladder to success, historically start more than a few rungs down from their male counterparts.

In the process of condemning the commodification of women’s bodies, “Generation Wealth” demonizes sexuality as a means of appealing to the men who profit most from the system anyway. And it fails to acknowledge sexual expression as anything but an unfortunate side effect of patriarchal capitalist culture’s blight. By embracing eroticism as a form of capital, Greenfield winds up alternately walloping and pitying the women who yearn for it and exude it. At times, her critiques of their lifestyle veer off the topic of wealth all together.

In the end, Greenfield’s cinematic portrait paints the Donald Trumps and Stormy Danielses of the world with the same broad brush.

Lauren Greenfield courtesy of Amazon Studios

For example, Greenfield invites “Generation Wealth” viewers into an upscale workout class, dubbed cardio striptease, where a room full of women spin around poles and dance suggestively as a teacher cheers them on.

“Let’s roll over and crawl and act like we like it,” the teacher says, as women move sensually on all fours. The smiles and laughter, however, suggest they genuinely do enjoy exploring their sexuality in such an open, though perhaps absurd, safe space. Greenfield interprets the scene differently. Even women who don’t financially benefit from their sexuality, she seems to argue, manage to exploit themselves. This is the capitalistic hellscape we occupy.

Cut to Magic City, a strip club in Atlanta, Georgia, where a combination of narration and hedonistic imagery cue the intended lesson. “At Magic City, beautiful girls use their sexual capital to rise to the top,” Greenfield proclaims, as images of naked black women dancing amid flurries of cash play on-screen.

“When I first started dancing, I felt like I made it,” Diamond, a stripper at Magic City, tells Greenfield. Her words play over footage of women on their hands and knees, gathering wads of money from the floor. “Being average has never been an option for me.” The intended juxtaposition ― Diamond’s words versus the reality Greenfield sees ― is cringeworthy.

Greenfield places the onus of responsibility not on the men treating women like objects (“I’m throwing money on a person, and she likes it!” a DJ who also works at the club says into the camera) but on the women who take pride in their work and their bodies for being blind to their supposed exploitation. Diamond doesn’t seem to possess the outrageously deep pockets of some of Greenfield’s other subjects, nor has she indicated in any way that stripping has negatively impacted her life. And yet Greenfield frames her as an unfortunate casualty in capitalism’s wake, conforming to the patriarchal underpinnings of the patrons and employers who might objectify her.

Lauren Greenfield, courtesy of Amazon Studios

But one need not venture into a strip club to witness women exploiting themselves, Greenfield argues. All you need is an internet connection. Although social media didn’t exist when her project began in the early ’90s, Greenfield suggests that it provides the perfect platform for women to Kardashian-ify themselves now.

Take it from Greenfield’s 15-year-old son Noah, who conducted an “Instagram study” on the subject, the findings of which wound their way into his mom’s doc. “I feel like a lot of my friends are in very revealing bikinis to make sure they get a lot of likes,” he says against a backdrop of Instagram photos of underage girls in bathing suits, their faces blacked out.

“Guys want what’s really demeaning to women,” Noah continues, as an nude selfie of Kim K. hits the screen. “To match guys’ expectations, I think lot of women try to replicate it.” A 15-year-old boy’s dogged conviction that scantily clad women are debasing themselves for men’s enjoyment is taken as fact, thereby amplifying the film’s overarching message that women are incapable of subverting the capitalist trappings thrust upon them.

Noah then discusses which Instagram posts don’t get as many likes: namely, in his experience, those which depict family. A cute family photo of the Greenfields flashes on screen.

Family, the film emphasizes, is the way out of our current consumer dystopia, and childbearing an antidote to women’s perpetual self-degradation. Most every hopeful moment in “Generation Wealth” revolves around family, and in particular, motherhood.

Suzanne, a workaholic who spent unseemly amounts of money on her personal appearance, describes feeling changed “so dramatically” by the birth of her daughter, whom she describes as “the prize.”

When she muses on her shifting spending habits, from contemporary art for herself to ballet classes for her daughter, the film’s happy Disney background music communicates a positive change has occurred. Never mind the fact that her spending seems just as exorbitant.

Lauren Greenfield courtesy of Amazon Studios

The sentiment continues as Greenfield revisits a woman named Mijanou, whom she initially met in 1994 as a high schooler in Los Angeles, when she was awarded “best body” of her graduating class.

As an adult, Mijanou is just as beautiful, though her style is more bohemian earth mother now. In the film, she runs with her daughter Sahaya through an idyllic field, conveniently located in the backyard of a mansion that she is probably not trespassing on, as she praises the benefits of “conscious parenting” and a TV-less lifestyle.

“I feel protective over her. She’s so beautiful,” Mijanou says of her daughter, before recalling the more painful memories of her own adolescence. “I think about that time, and how even I used to dress, and I’m now like, oh my God, I would never want Sahaya to go out like that.”

She’s framed as having escaped consumerism’s devilish grips, primarily by covering up and giving birth.

Overall, the documentary provides a wild glimpse into the highest ranks of wealth. And it admits that, under capitalism, women get the short end of the stick. However, by framing family as the ultimate panacea to the damage consumerism inflicts, and caricaturing the women whose priorities remain elsewhere, Greenfield muddles her point.

She fails to consider that child-rearing isn’t an antidote to income inequality, but in fact, a sure way to perpetuate it.

[ad_2]

Source link