[ad_1]

“Show me a happy homosexual, and I’ll show you a gay corpse,” a swanning Catholic with maxed-out credit cards and a snazzy Manhattan apartment sneers in “The Boys in the Band,” a play that has done little but sour since 1968, when it premiered Off-Broadway like a sizzling cherry bomb.

That year is significant: It’s the moment Hollywood’s prudish production code — which considered homosexuality “sex perversion” — fully crumbled, opening the door to grittier, more candid cinema. It’s also the year the DSM changed its classification of homosexuality from outright paraphilia to mere “sexual orientation disturbance.” (How generous.) The world was, in some sense, readying itself for the Stonewall riots of 1969 and the approaching decade’s queer crescendo: the steady decriminalization of gay behavior, the election of Harvey Milk, the free-love mecca that was Studio 54. Mart Crowley, the playwright responsible for “The Boys in the Band,” had a hand in steering culture in that direction.

And yet, from the moment the play debuted, and even more when William Friedkin turned it into a movie in 1970, “Boys” was divisive. On the one hand, gay visibility made headway on the national stage; on the other, it did so via a stereotypical portrait whose self-loathing characters became a sad generational touchstone.

The tragicomedy’s central “band” — eight gay men (including a hired hustler) and one maybe-straight interloper gathering to celebrate their friend Harold’s 32nd birthday — comprises a treasury of show-offs forever one-upping each other with biting quips and clawing jabs. Alcohol flows, blood spills, resentments emerge. This, according to Crowley’s writing, is what cosmopolitan gay companionship looked like in the pre-internet era: dipped in vinegar and flecked with the antipathy of Edward Albee’s “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” Today’s talk of “communities,” “safe spaces” and “normalization” was coded at best. But there wasn’t much queer-themed pop culture to be found, and “The Boys in the Band” proved immensely popular, running for more than 1,000 performances in New York and mounting a rendition in London.

Joan Marcus

“The power of the play […] is the way in which it remorselessly peels away the pretensions of the characters and reveals a pessimism so uncompromising in its honesty that it becomes in itself an affirmation of life,” New York Times theater critic Clive Barnes wrote in his 1968 review, while nonetheless noting that the “frightening self-pity” is “laid on too thick at times.”

Reviews for Friedkin’s faithful screen adaptation, while generally favorable, were split on the impact of its portrayals. A Time magazine critic whose byline is not listed on the site wrote, “If the situation of the homosexual is ever to be understood by the public, it will be because of the breakthrough made by this humane, moving picture.” Meanwhile, New York Times critic Vincent Canby eloquently opined, “There is something basically unpleasant, however, about a play that seems to have been created in an inspiration of love‐hate and that finally does nothing more than exploit its (I assume) sincerely conceived stereotypes.” Made before “The French Connection” and “The Exorcist” turned Friedkin into one of Hollywood’s hottest directors, “Boys” became a cultural petri dish but not a mainstream smash.

CBS Photo Archive via Getty Images

What do we do with “The Boys in the Band” in an age when queer portrayals have graduated from its uncompromising brand of acidic tyranny? Revive it, of course.

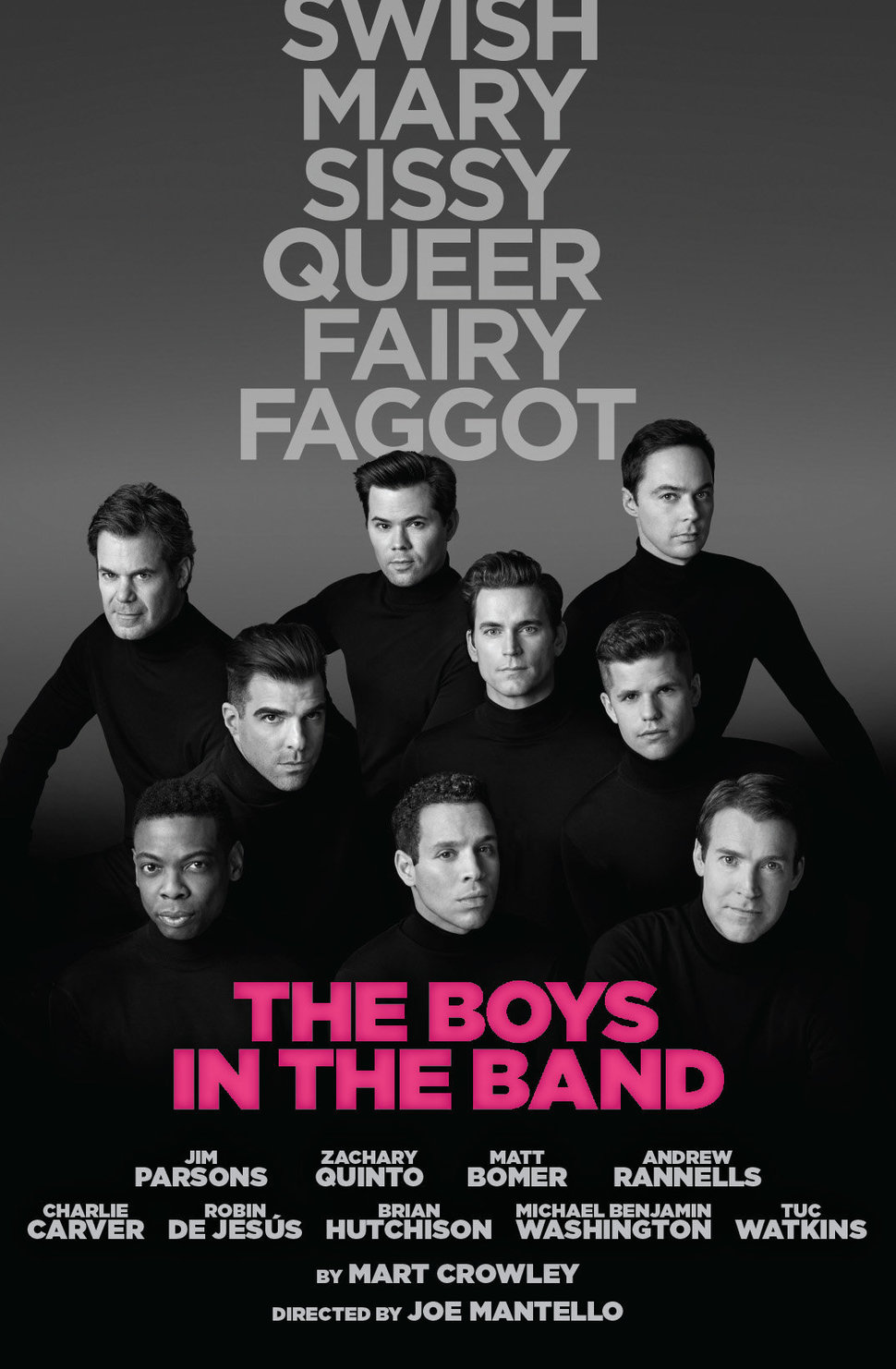

At least that’s what Broadway is choosing to do right now. Directed by theater deity Joe Mantello, “Boys” opened May 31 with the starriest and handsomest cast currently occupying the Great White Way: Jim Parsons, Matt Bomer, Zachary Quinto, Andrew Rannells, Charlie Carver, Robin de Jesús, Tuc Watkins, Michael Benjamin Washington and Brian Hutchison. Each of these actors is openly gay, a fact that resonates 50 years after the initial production, as several of the gentlemen who originated their roles later died from AIDS without achieving half of Quinto’s or Carver’s fame.

For this reason and more, “Boys” is a relic of a bygone era — the final moments of queer invisibility, a depiction of flamboyance untouched by the “gay cancer” scare that would soon devastate the world, a time when any gay representation whatsoever was both subversive and encouraging, and a point in American history when everything about the LGBTQ experience was haunted by fear, retribution and, yes, self-loathing.

Today, even if gay prosperity is still a battlefield, these evils no longer prescribe an entire demographic’s way of life. It’s the age of “Moonlight” winning Best Picture, Laverne Cox landing the cover of Time, Ryan Murphy dominating primetime television, Janelle Monáe labeling herself pansexual, Troye Sivian twinkifying pop music and Tammy Baldwin enjoying her 19th year as a congresswoman.

In keeping, “Boys” feels like little more than an outdated artifact. Read generously, it serves as a marker of how far removed we are from gay men pejoratively calling one another “nelly queens.” But accepted at face value, it is a nasty 110 minutes of theater, and a misuse of a cast that would be better served with fresh material that has more to say about the complex ways non-heterosexual folks live their lives, now or in the late ’60s.

Polk Co

For all its sharp banter and barbed one-liners, “The Boys in the Band” flattens its characters into archetypes. What must have been exciting about that paradigm circa 1968 reeks of fatigue in 2018, especially when it’s stamped across the revival’s memorabilia in such a literal way. At the Booth Theater, you can spot posters and purchase T-shirts that list six taunts in capital letters: “Swish. Mary. Sissy. Queer. Fairy. Faggot.” Whatever power there is in reclaiming these insults is diminished by the hopelessness of the characters they are meant to represent.

Trimmed down from Crowley’s preachier original text, this one-act production does little to wink at or tame its debasement. As booze and blunts dampen the friends’ joviality, the party’s host, Michael (Parsons), suggests a game: Everyone must call the one person he truly loves and confess his feelings, knowing they are likely to be unrequited. Michael keeps score. The winner will inevitably be the participant who most embarrasses himself, the lightweight reduced to a daze of bitter tears.

It’s in this activity that the group is forced to reckon with just how lonely their individual lives are, how hard it is to find anything resembling a soulmate and, most crushingly, the fickleness of the support they receive from their so-called friends. A barrage of insults follows. Michael hurls the N-word at the show’s only black character, and the religion, promiscuity and luxury goods to which these men sometimes cling becomes an existential critique. By the end, we are left with one cheap glimmer of hope: Harold (Quinto), an old-school stereotype of a tart-tongued princess who disguises his ugly appearance with fabulous clothes, turns to Michael on his way out, promising to call him tomorrow. That is the play’s definition of community. Havoc will be wreaked by night, but everyone will pretend to be chummy, more or less, come morning. They have few others to turn to. The cycle is unbreakable.

And that’s where “The Boys in the Band” trips over its own complicated feet. Self-doubt is bred into queers from the moment their identities half-crystallize. What that looked like in the 1960s is still relevant today, because the mantras with which these characters exist haven’t completely faded from our collective consciousness. But “Boys” wants to have it both ways: It tries to be “Virginia Woolf” and “La Cage aux Folles.” In grafting a semblance of optimism onto this vicious soap opera, Crowley’s work sputters. It fails to convince us that these fellas need each other, that their lives in the big city aren’t anesthetized by parties and glitter, that this potboiler serves much purpose beyond letting the audience pant at the sight of Matt Bomer in tighty-whities.

Joan Marcus

After the 1970s, the “Boys” tide had fully turned. In his influential 1980 book The Celluloid Closet, the gay film historian Vito Russo called Friedkin’s movie the “most potent argument for gay liberation ever offered in a popular art form” ― more of a plea for social progress than a compliment of the art. When the play was revived Off-Broadway in 1981, New York Times theater critic Alvin Klein declared it “as psychologically passe as it is dramatically dated” and challenged its “maudlin self-indulgence.” Several years before queerness exploded on-screen and onstage, “Boys” was already a faux pas. When it returned again in 1996, New York Times criric Ben Brantley had a measured reaction to its “bitchy insult humor” but arraigned it as a “creaky piece of craftsmanship, neatly tailored to a fault and far too intent on explaining itself.”

Reviewing 2018′s rendition, Brantley’s words are harsher: “This real-time drama only rarely seems to be happening in real time, with real feelings. […] I had to strain to imagine the boys of ‘Boys’ were a blood-bound clan, better known to one another than their natural-born families were. And without that illusion of chosen consanguinity, the expositional creakiness of Mr. Crowley’s script is laid unflatteringly bare.”

Leaving the theater last weekend, I thought of the many hopeful endings that queer stories of late have told: the ham-fisted romance in “Love, Simon,” the bittersweet joy of “Call Me by Your Name,” the final reunion in “Carol,” the eroticism of “Blue Is the Warmest Color,” the everydayness of “The Kids Are All Right,” the sweet self-discovery of “Dear White People,” the youthful sensuality of “Riverdale,” the spectrum of sexuality on “Sense8,” the genuine community-building on “Orange Is the New Black.” By no means is happily-ever-after the only option for queer characters, but works that revel in pessimism need to say something tactile about such despair.

In fact, one of my favorite pieces of recent queer pop culture distinctly lacked the positivity we yearn for. Earlier this year, “The Assassination of Gianni Versace: American Crime Story” opened and closed with gay spree killer Andrew Cunanan murdering the titular gay designer. A Ryan Murphy endeavor through and through, the FX show was coated in darkness, a far cry from any of the upbeat portrayals we’ve demanded in the years since LGBTQ characters were routinely punished or villainized. And yet there was a catharsis to the series that “The Boys in the Band” lacks. “Versace” offered a painful and detailed reminder of what self-loathing can do to a person, and to a community. It showed more than vodka tumblers and confetti scraps strewn across a sassy man’s expensive living room.

“Versace” has a poetry that “Boys” does not, largely because it never reduces Cunanan or anyone who orbits him to a caricature. In juxtaposing Cunanan and Versace’s disparate work ethics and quests for fame, Murphy created a textured dynamic. Behind every performative gesture lurked a deeper tragedy indicting the malevolent strictures that turned Cunanan into a ladder-climbing con artist incapable of loving himself or others.

“The Boys in the Band,” on the other hand, barely lets the audience in on these guys’ interiority outside the chambers at which they gather. By the time it asks us to rip ourselves open alongside them, Crowley’s intentions remain unclear. To revel in so much rancor ― an American theater tradition as old as Broadway itself ― is to wonder why, in 2018, this is the memento worth excavating. Surely we’ve found more to say about the agony and ecstasy of the gay experience.

#TheFutureIsQueer is HuffPost’s month-long celebration of queerness, not just as an identity but as action in the world. Find all of our Pride Month coverage here.

[ad_2]

Source link